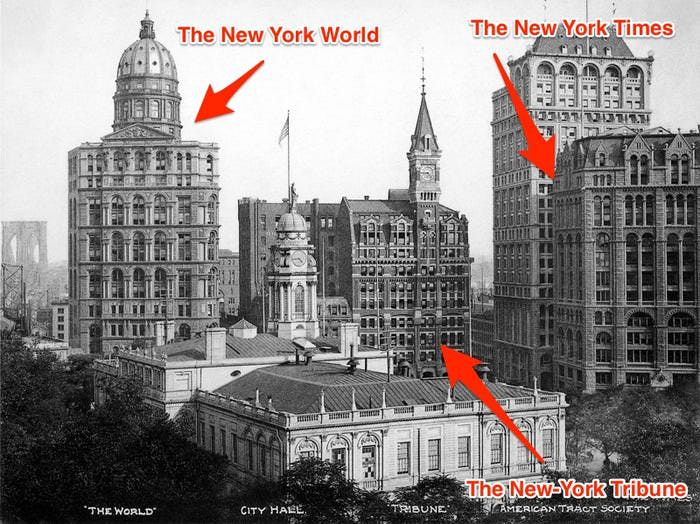

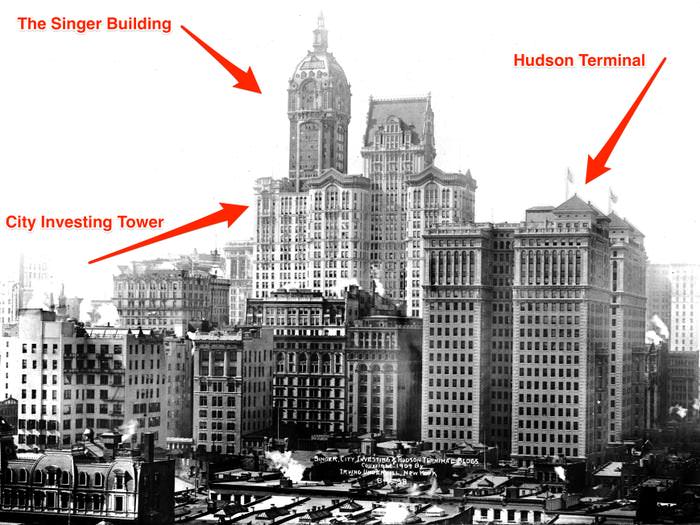

New York City constantly rebuilds itself. Towers rise, fall, and rise again. This cycle has shaped the city’s skyline but has also erased many historic landmarks. The reasons behind these losses aren’t random. They follow patterns tied to development pressure, land value, political decisions, and shifting tastes.

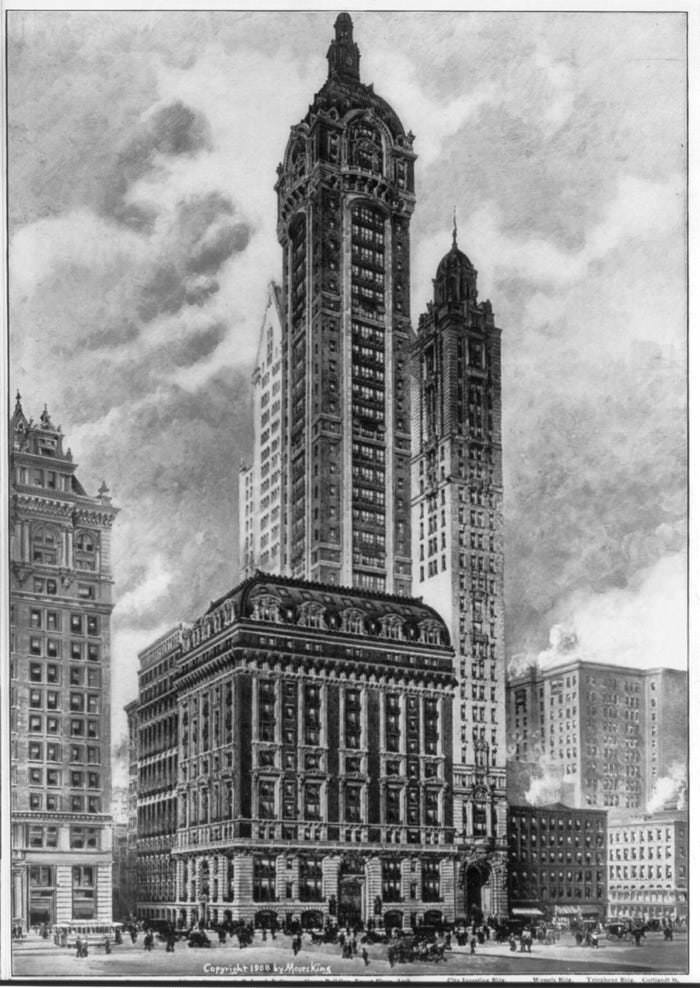

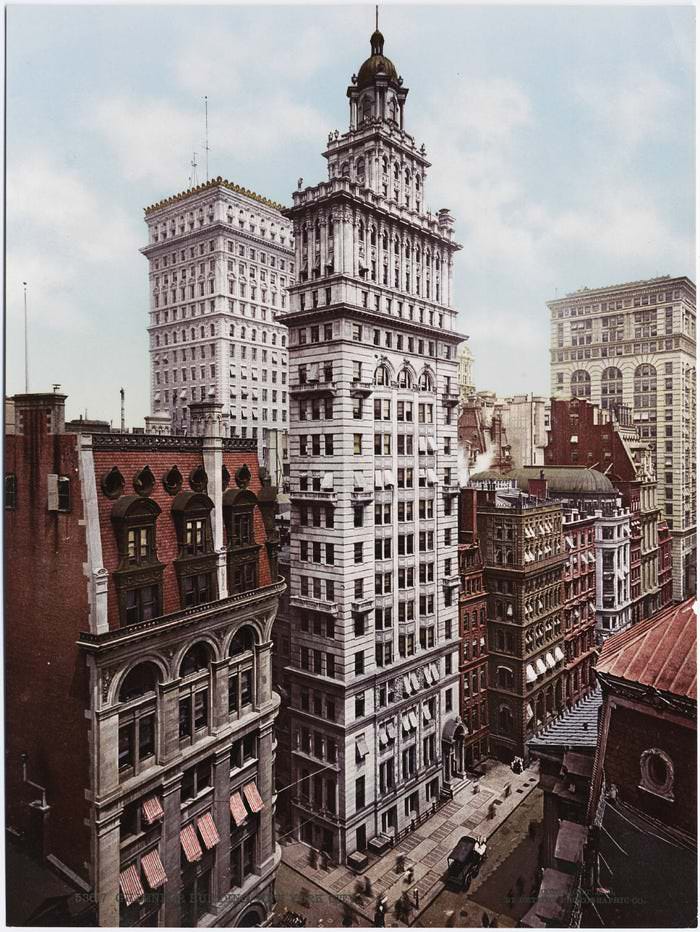

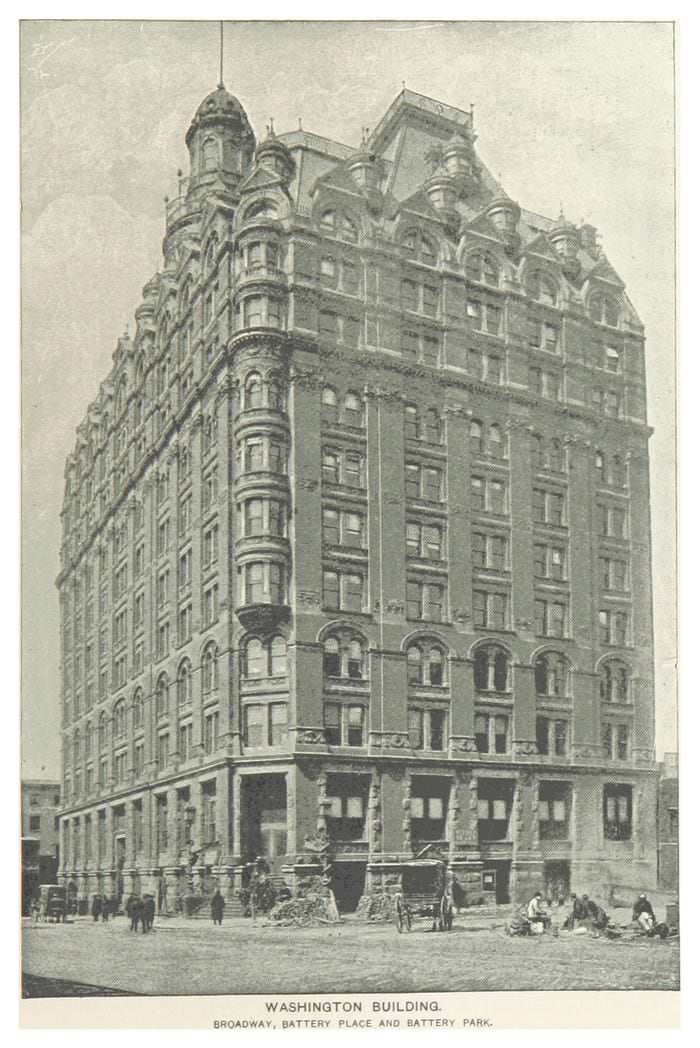

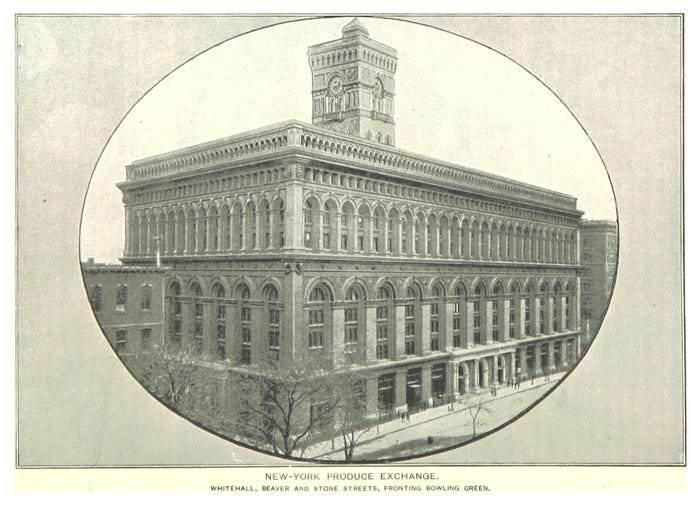

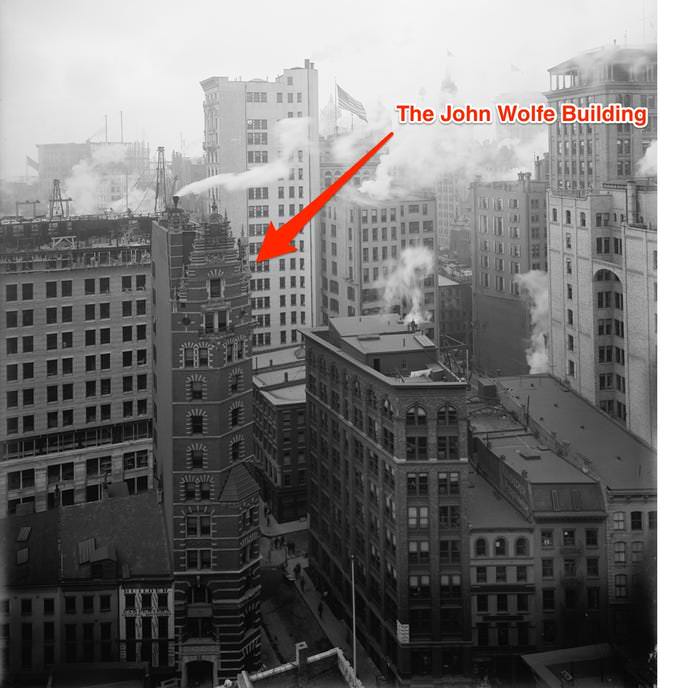

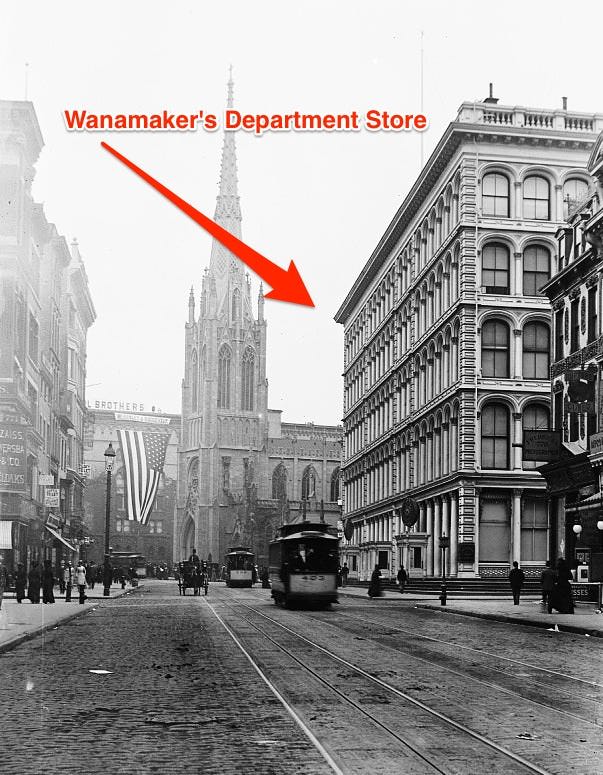

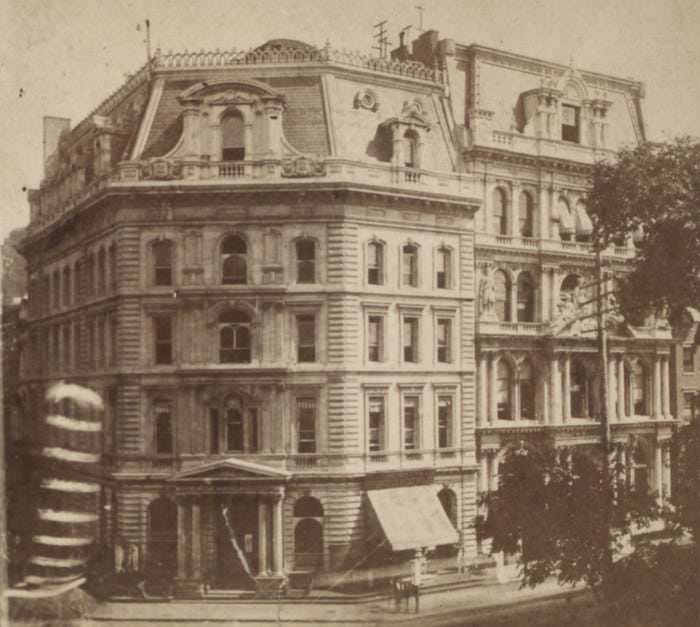

From the mid-19th century through the 20th century, demolition was often driven by one thing: land value. As Manhattan real estate prices soared, many older buildings became more valuable as empty lots than as preserved landmarks. A historic opera house or a luxury mansion could no longer compete with the profits of a high-rise office tower. When buildings like the Singer Building or the original Penn Station were torn down, developers were looking to maximize square footage and returns. In lower Manhattan especially, this pressure was constant.

Zoning laws and changes in building codes also helped push out older structures. In many cases, buildings constructed before modern fire, elevator, or structural safety rules couldn’t be brought up to code without major investment. Owners often chose demolition over expensive retrofits. Fire risk played a major role in the loss of early high-rises and grand homes made of timber and plaster.

Read more

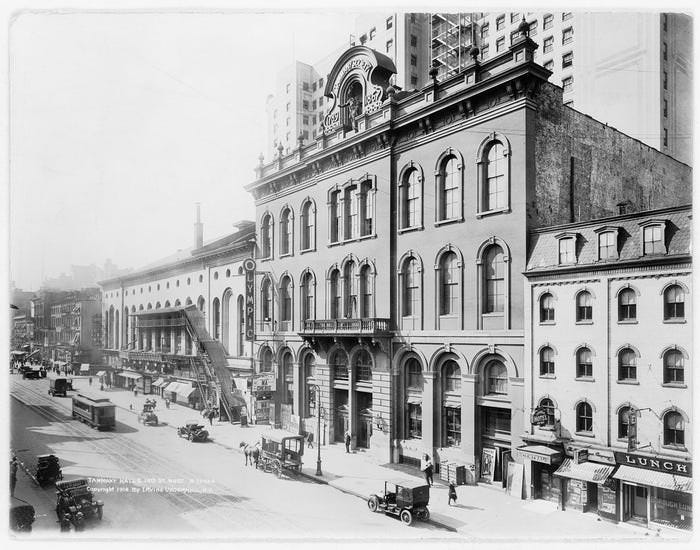

Postwar development policies in the 1950s and 1960s added to the problem. Urban renewal became the official policy of the city. Federal funding supported large demolition projects in the name of progress. Officials viewed older buildings as outdated, inefficient, or symbols of urban decline. Entire blocks were cleared for highways, offices, and modernist housing. This wave hit neighborhoods like Times Square, lower Manhattan, and parts of Brooklyn especially hard.

Transportation projects also wiped out historic buildings. Penn Station wasn’t alone. Grand hotels, churches, and social clubs were displaced by tunnels, train yards, and terminals. In many cases, new infrastructure required large footprints and deep foundations. The past had no place in these plans.

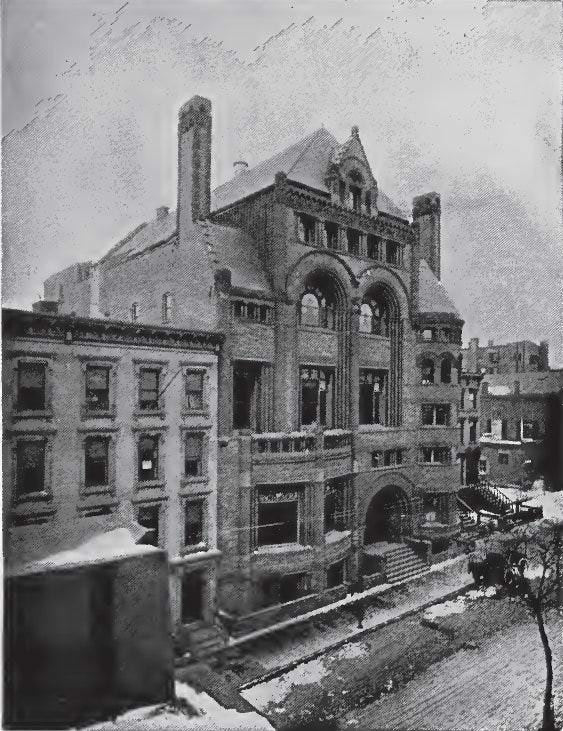

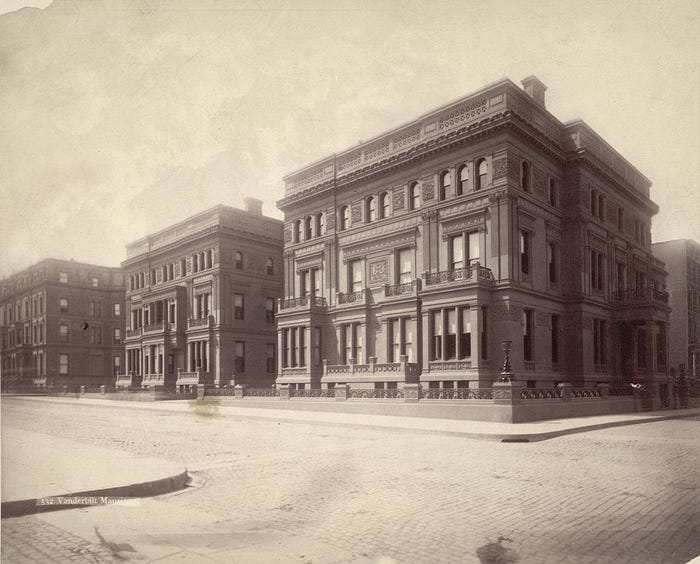

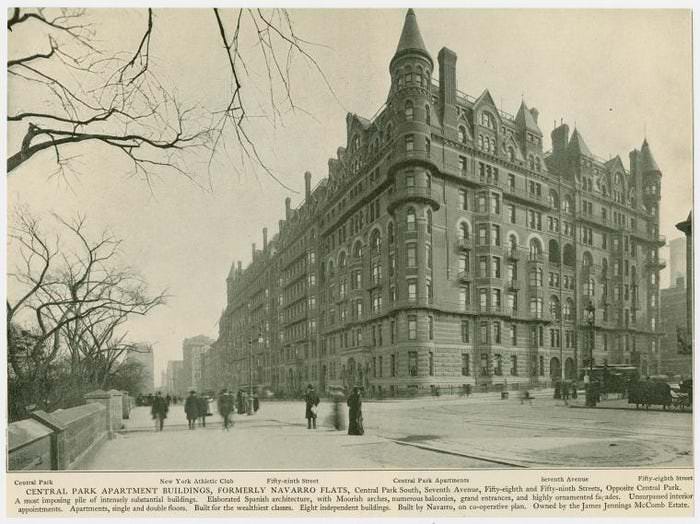

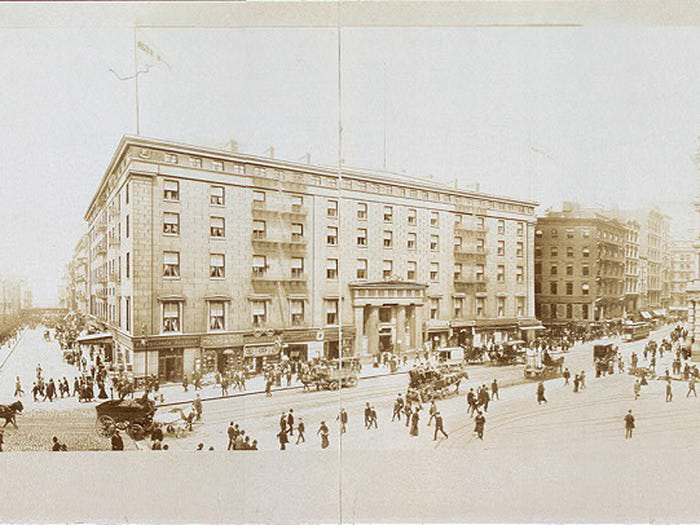

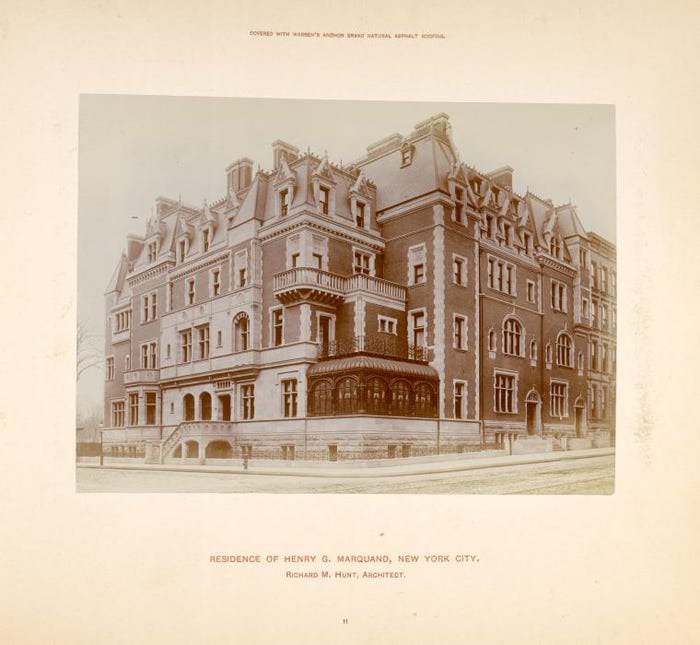

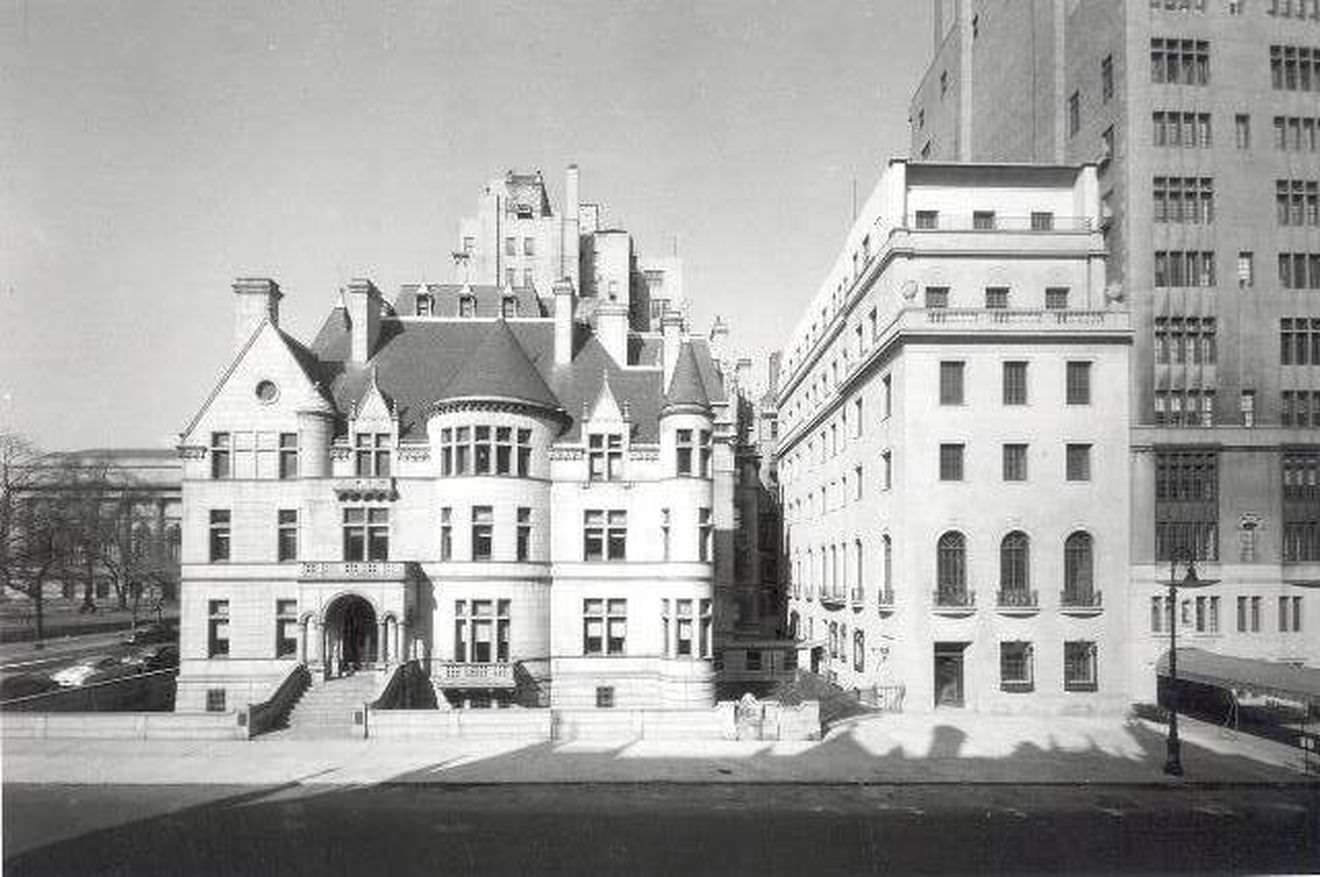

Cultural shifts played a subtler role. In the early 20th century, the city’s elite lived in mansions lining Fifth Avenue. But by mid-century, wealth moved to the suburbs or penthouses, and the old estates became outdated. Once the families left, their homes were sold off and replaced with apartment buildings or offices. Public taste moved away from heavy, ornate architecture. People favored glass, steel, and minimalism.

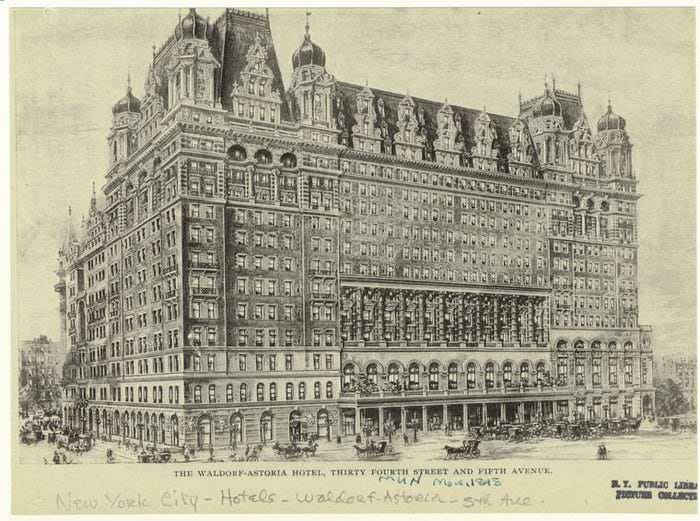

Another key factor was the lack of preservation laws. Until 1965, there were no strong legal protections for historic sites. Owners could demolish even architecturally significant landmarks without delay. This lack of protection led to the destruction of major icons like the original Waldorf-Astoria and many Vanderbilt mansions. The outcry after Penn Station’s demolition eventually helped launch the landmarks preservation movement, but by then, much had already been lost.

Politics and personal power shaped demolition choices too. Developers with strong ties to city officials could push projects through despite public opposition. Buildings stood or fell not just based on condition or value, but on who owned them and what deals were made behind closed doors. In some cases, demolitions were fast-tracked without public hearings or media attention.

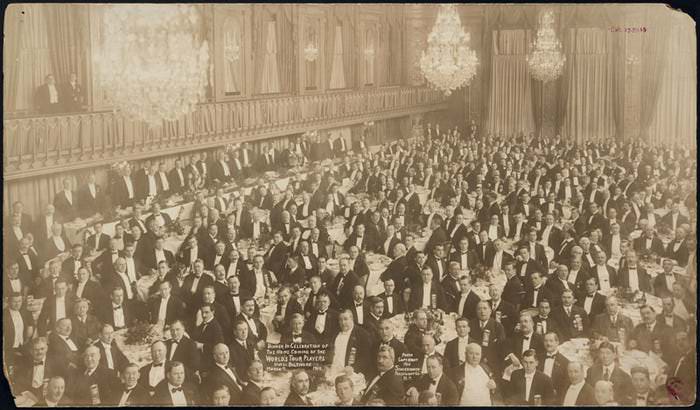

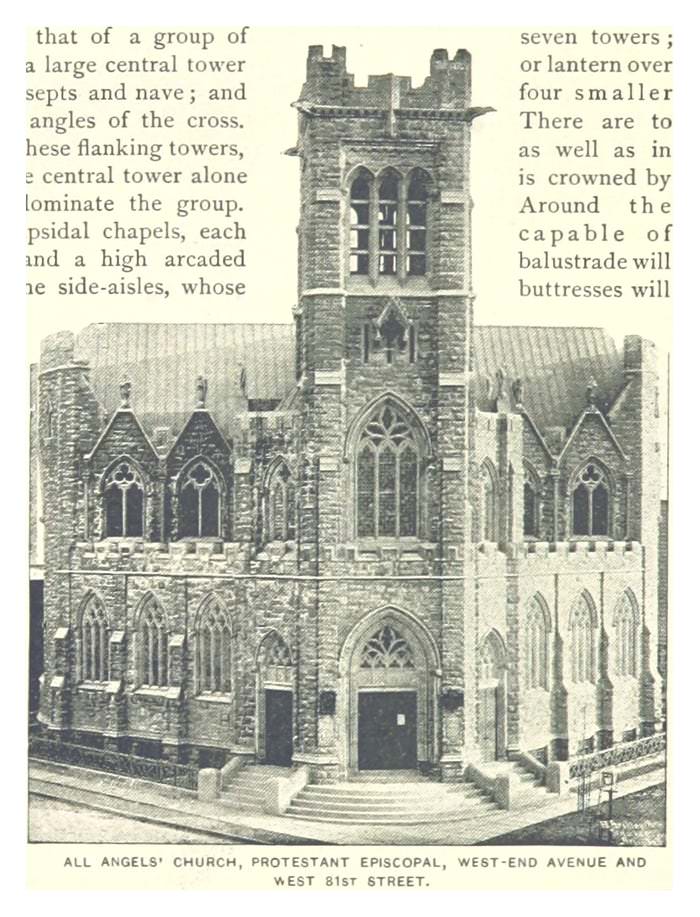

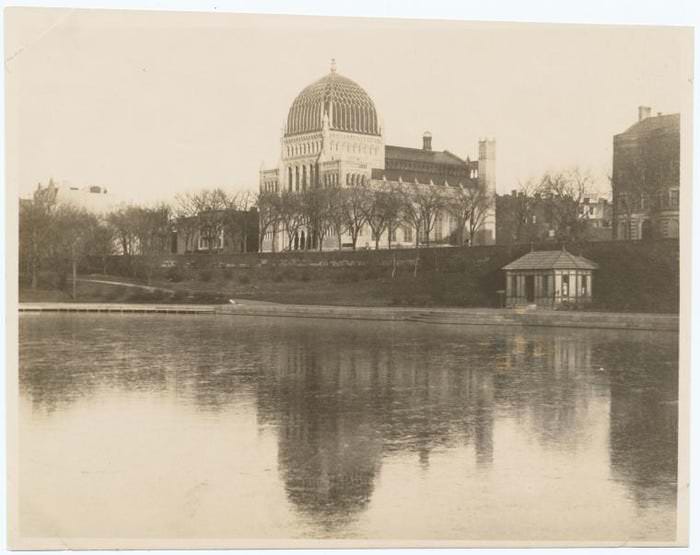

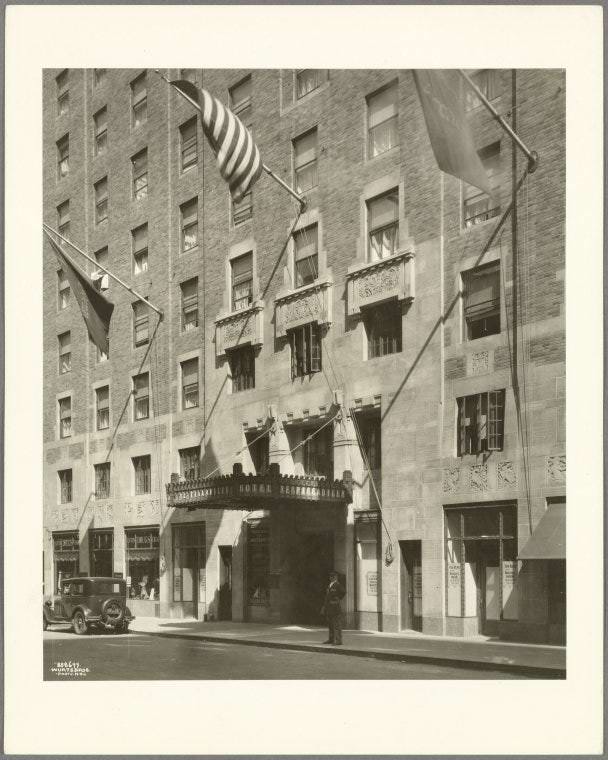

Some demolitions happened not out of necessity, but because of indifference. Social clubs, churches, and theaters lost members or funding. Once empty, these buildings sat neglected and decayed. Without public use or money for repairs, they became easy targets for redevelopment. The loss of neighborhood anchors like the Ziegfeld Theater or the Germania Club followed this pattern.

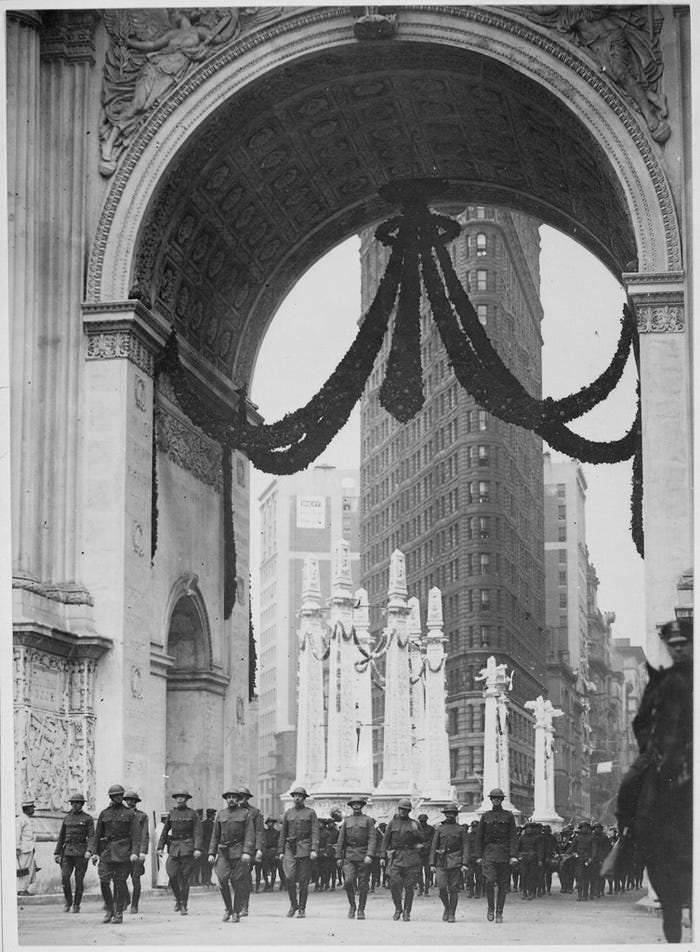

Occasionally, new ideas drove old ones out. Buildings were torn down for symbols — arches, monuments, or modern cultural centers. The city removed some structures not for money or decay, but to change how it wanted to be seen. It replaced history with statements of the present.

In most cases, the demolitions weren’t about one single reason. Often, it was a combination: a grand hotel might fall because its style was out of fashion, its systems outdated, and the land beneath it worth millions. Layered decisions erased layers of history.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings