In the early 1900s, New York City faced a major public health problem: most people didn’t have access to private bathtubs or showers. Tenement buildings were packed with families, and indoor plumbing was rare. To improve sanitation and provide relief during hot summers, the city built public swimming pools and floating baths.

The first floating baths appeared in the 1870s, but by 1900, they had become more advanced. These wooden structures sat on the East and Hudson Rivers, supported by pontoons. Water flowed in through slatted bottoms, so swimmers were actually in the river. The water wasn’t clean by today’s standards, but it was better than nothing. The city moved the baths each season to different docks depending on the water conditions.

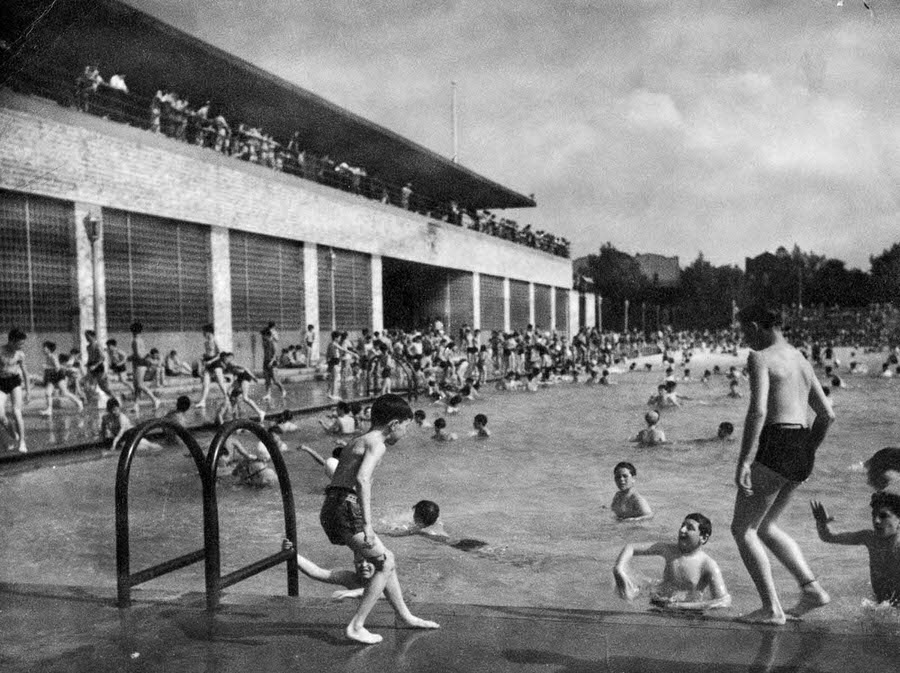

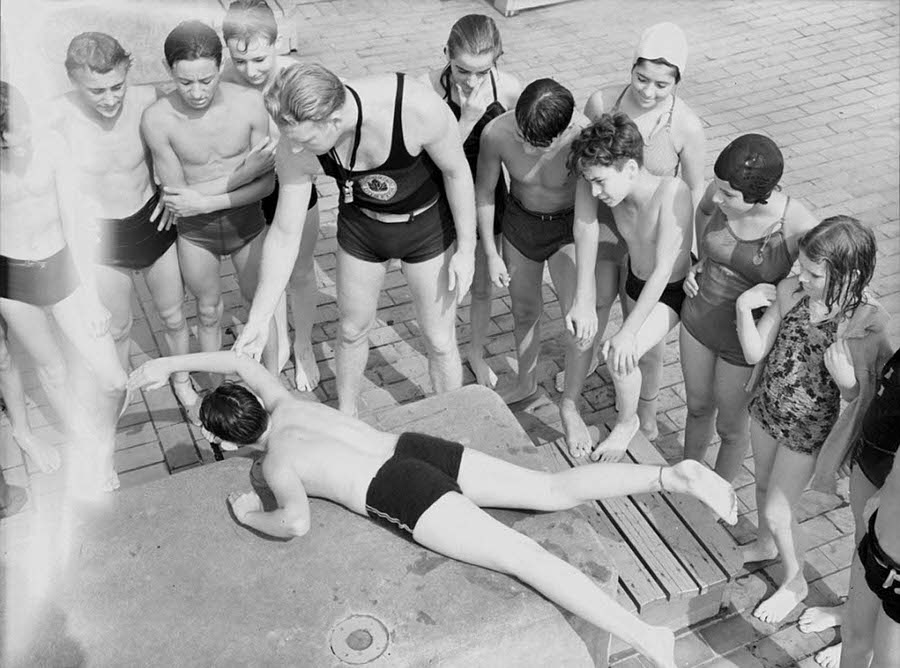

Each bath had strict rules. Boys and girls swam at different times. Lifeguards were present, and bathers needed to follow safety instructions. Visitors had to wash before entering the water, using soap provided by the attendants. Some of the baths could handle over 10,000 swimmers in a single day. At night, the facilities were cleaned, and supplies restocked for the next rush.

Read more

By 1901, there were over a dozen floating baths in the city. One of the most used was located at East 26th Street. Another popular site sat off the West 40s. These structures were free and open to anyone. Many young New Yorkers learned to swim there. While they served a basic function, the design was practical. Some had changing rooms and wooden lockers. Others added showers as water systems improved.

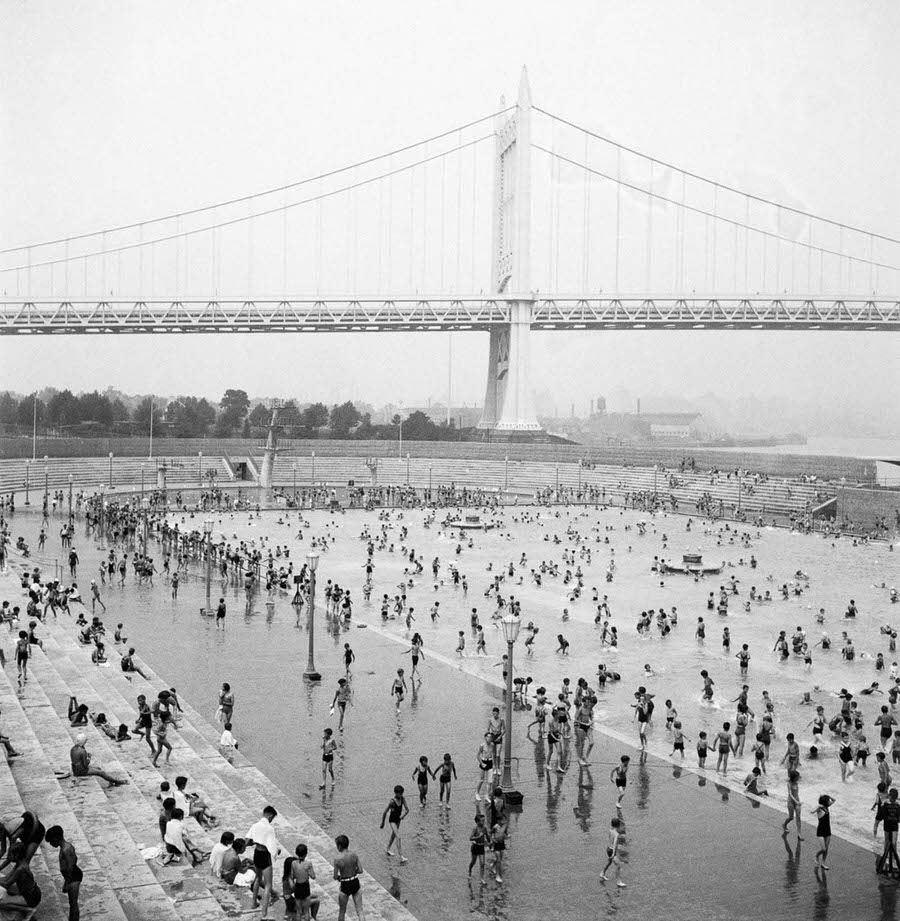

As the city grew, so did the demand for permanent pools on land. The Department of Public Baths began planning more advanced structures. One of the first large public indoor pools opened in 1901 on Rivington Street in the Lower East Side. The building had a red brick exterior and Roman-style arches. Inside, the tiled pool was 100 feet long, with skylights that let in natural light. Hundreds of people lined up daily to swim, clean off, or simply cool down.

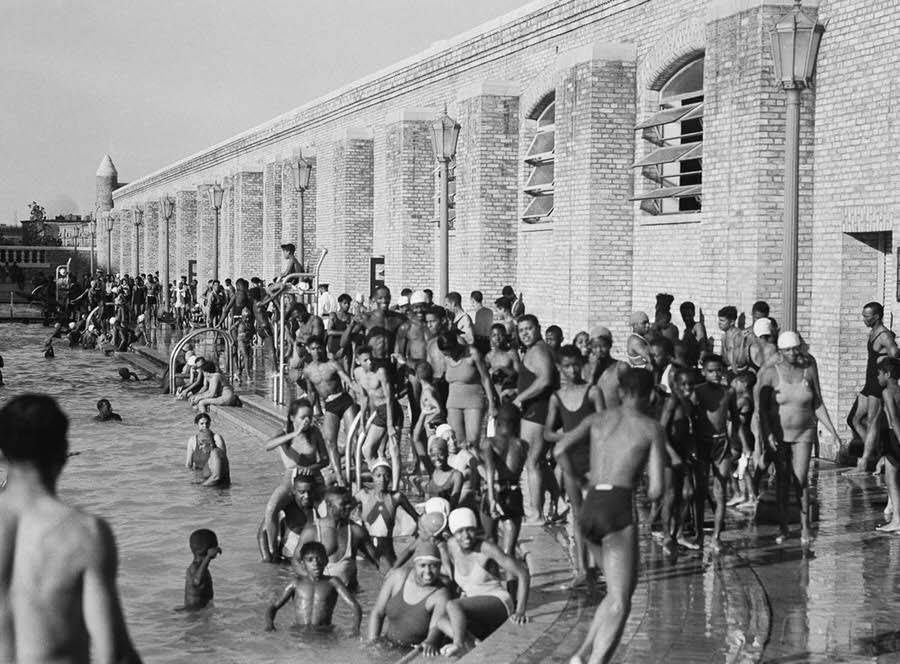

These new facilities weren’t just pools. They included public baths, laundry areas, and sometimes classrooms for hygiene education. The city understood that improving personal cleanliness could prevent disease outbreaks. Immigrants and low-income families, who made up much of the population, depended on these places.

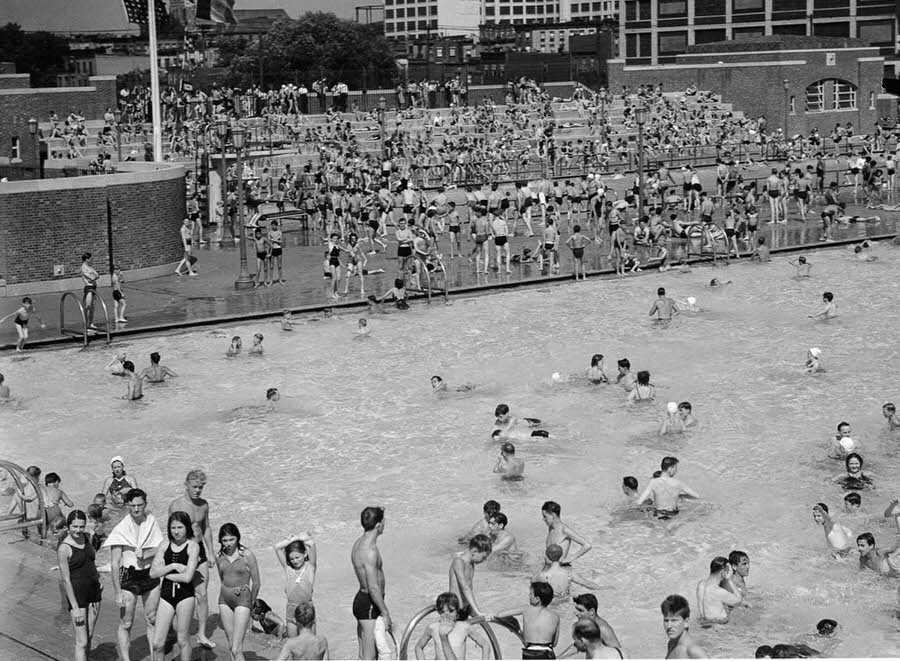

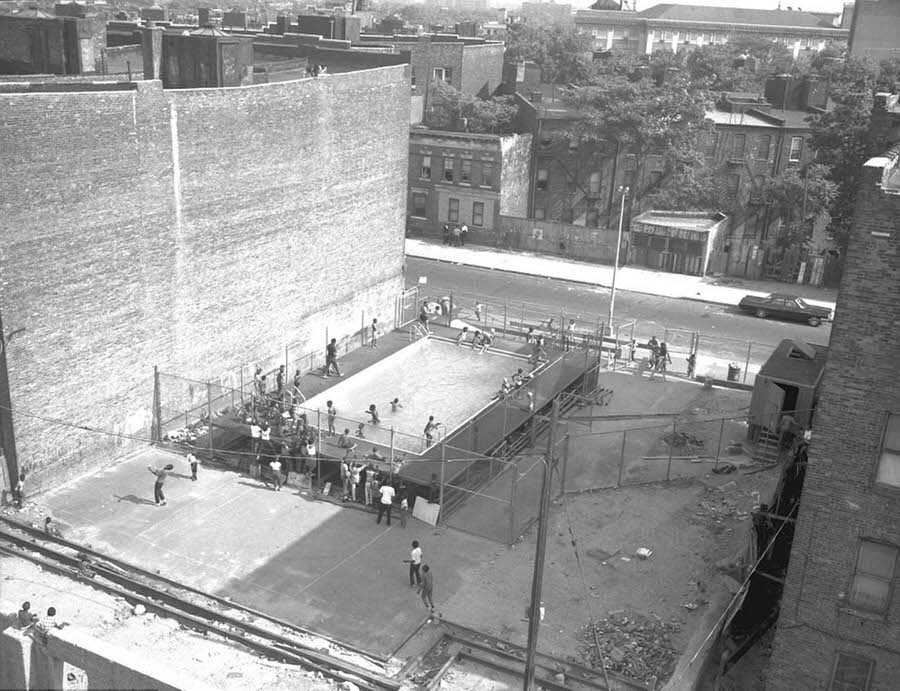

The city also built outdoor pools during this time. These had concrete basins and often stood in open lots between buildings. One outdoor pool in Brooklyn, built in 1906, was 120 feet long and hosted swimming competitions. Young swimmers trained there in hopes of joining local amateur teams. These contests drew crowds and encouraged athletic growth in working-class neighborhoods.

Temperatures in New York summers could reach over 90 degrees. Air conditioning didn’t exist, so public pools were more than just recreational spaces. They were necessary. Some pools had limited hours due to staffing shortages, and swimmers would line up early to guarantee entry. Police often helped manage crowds during peak days. In some locations, food vendors set up nearby to serve waiting families.

By the 1910s, new pools began using filtered water, which made swimming safer. Filtration systems reduced the risk of infections and allowed the city to abandon river-based floating baths. Several of those were taken out of service and dismantled. The land-based models offered greater control over cleanliness and structure.

Swimming pools also played a role in social policy. Public officials used them to promote discipline and order. Rules banned rowdy behavior and required proper swimwear. Boys wore one-piece suits that covered the chest. Girls had separate hours and were often supervised by female attendants. These rules reflected the moral expectations of the time.

Public pools were segregated by both gender and sometimes by race. In some neighborhoods, Black residents were unofficially excluded from using certain facilities. While there were no laws forcing this, discrimination often came from how the spaces were managed or who was allowed to work there.

Some schools began building pools of their own to teach swimming as part of physical education. Programs aimed at reducing drowning incidents were common. Instructors led group lessons, and students practiced floating, breathing, and basic strokes.

By 1920, New York had dozens of land-based public pools in operation. They varied in size and style, but all had a common purpose: to serve the city’s growing population. Some were grand, built with columns and murals. Others were plain but functional. Regardless of design, they offered something vital — a way to stay clean, cool, and connected in one of the world’s busiest cities.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings