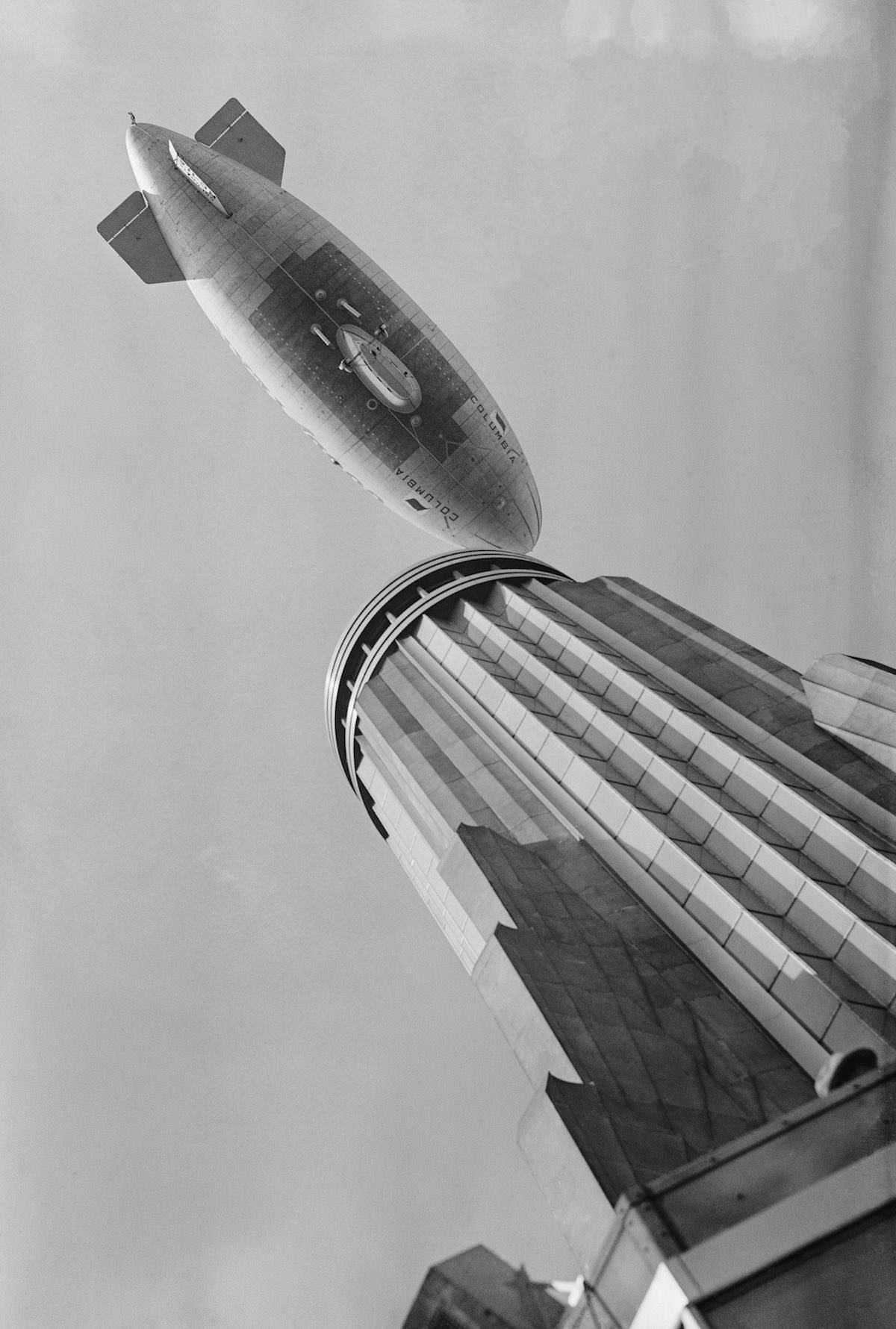

The Empire State Building was built in New York City during the Great Depression. Construction started in March 1930 and finished in just over a year, in May 1931. At the time, it became the tallest building in the world. It reached a height of 1,250 feet at the roof, and with the antenna added later, the full height was 1,454 feet. Building something that tall in such a short time was not common. It was a massive effort involving thousands of workers, dangerous conditions, and constant pressure to move quickly.

The workers included riveters, steelworkers, crane operators, and electricians. Many came from immigrant families. A large number of them were Mohawk ironworkers from Canada, known for their skill and fearlessness when working at great heights. Others came from Europe or the American South. Most of the laborers did not have formal safety training. They learned on the job and were expected to keep up with fast schedules.

The pace was intense. Construction crews added an average of four and a half floors each week. That required precise planning and coordination. Materials had to be delivered on time. Workers had to know exactly what their tasks were. There was no room for delays. Trucks delivered steel beams to the site, and elevators brought them to the right floors. Cranes lifted heavy pieces into place. Workers guided and bolted them in while balancing on narrow steel girders, sometimes over 1,000 feet above the ground.

Read more

There were no harnesses, hard hats, or safety nets for most of the workers. Men walked across narrow beams with no railings. They carried heavy tools and materials while doing it. Some worked while strong winds blew around them. Others ate lunch while sitting on beams high above the street. The risk was constant. A single mistake could lead to a fall. Some workers died during construction, though the official count remains debated. The number was low compared to other buildings of the time, but the dangers were always present.

Most of the steelwork was completed in six months. Over 57,000 tons of steel went into the frame. The building’s skeleton rose fast, and each new floor added more risk. Workers sometimes stood shoulder to shoulder while guiding beams into place. They used hot rivets to fasten the steel. One worker would heat the rivet in a furnace. Another caught it in a bucket or glove. A third drove it into place with a pneumatic hammer. This system required speed, accuracy, and trust among the crew.

The size of the project required a huge workforce. At its peak, about 3,400 workers were on-site every day. There were ironworkers, carpenters, plumbers, electricians, and stonecutters. Everyone had to do their part without slowing the rest of the crew. Delays in one area could stop progress in others. The men worked long hours, sometimes in tough weather. Winter winds could freeze bare hands, and summer heat made steel surfaces burn to the touch.

The design of the building helped speed up construction. It used pre-made steel pieces that were assembled on the ground and lifted into place. Windows and interior walls were also produced off-site. This allowed the workers to focus on assembly instead of building each piece from scratch. The building was designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon. Their plans balanced strength with simplicity, which made construction faster and safer.

Coordination between teams was critical. While steelworkers built the frame, other crews followed behind to install walls, plumbing, and wiring. Elevators were added quickly so that workers didn’t waste time climbing stairs. Supplies were moved by hoists, and tools were passed from one worker to another. Communication was often done by hand signals or short calls shouted through the noise. Everyone knew what they had to do and when.

Construction didn’t stop when the weather changed. Rain, snow, and fog all hit the site during the year-long build. Workers kept going through it all. They wiped surfaces dry before using tools. They added grit to their boots for grip. In thick fog, they relied on each other’s voices and careful movement to stay safe. When lightning storms hit, work paused, but only for as long as necessary. Every day counted.

One of the most difficult parts was installing the steel beams near the top of the building. The higher the structure got, the more it swayed. Tall buildings move slightly with the wind, and workers had to adjust for that while placing beams and rivets. They used ropes, bars, and clamps to hold parts in place. Sometimes they waited for the wind to slow before continuing. They balanced on beams as thin as a few inches wide, with nothing between them and the street below.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings