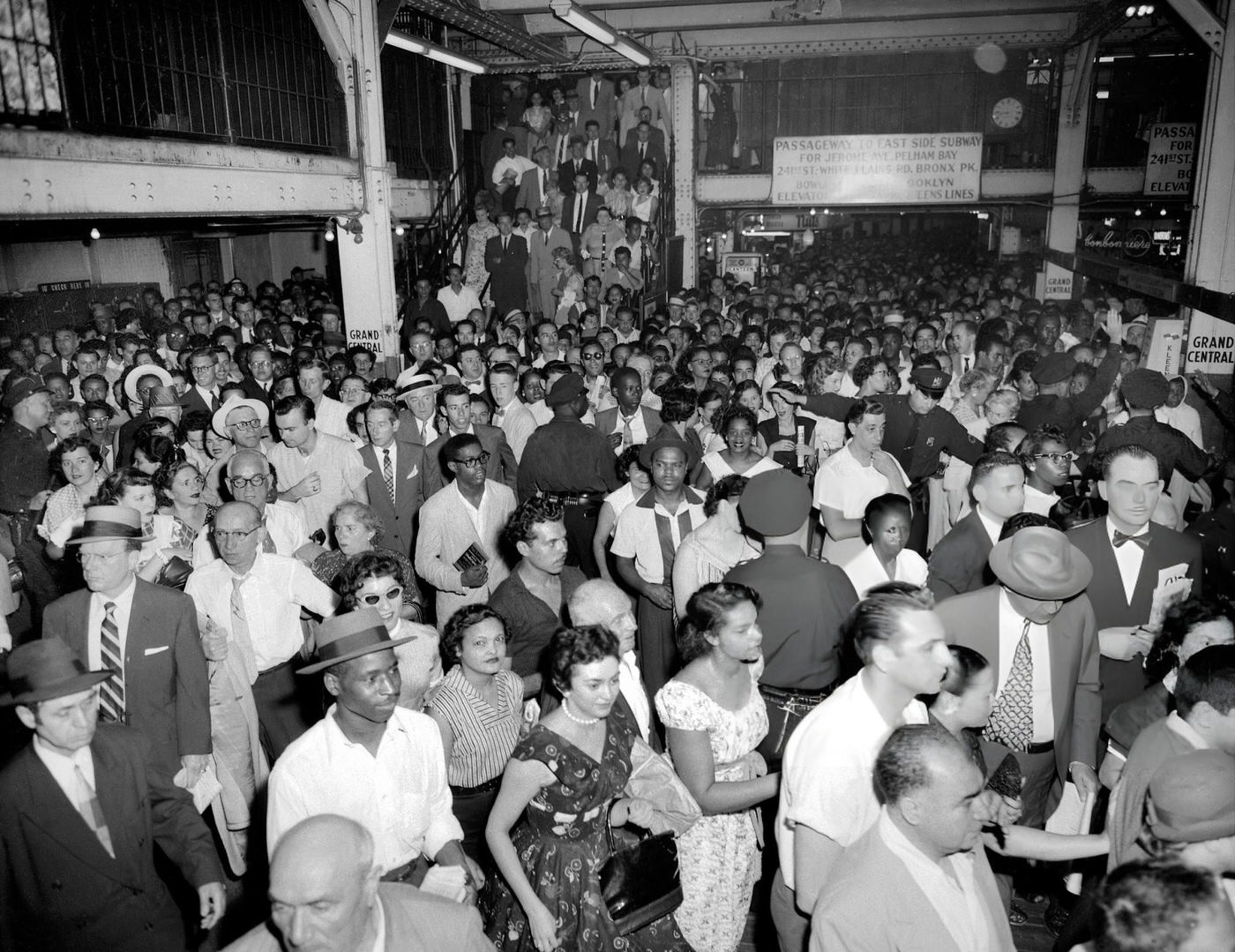

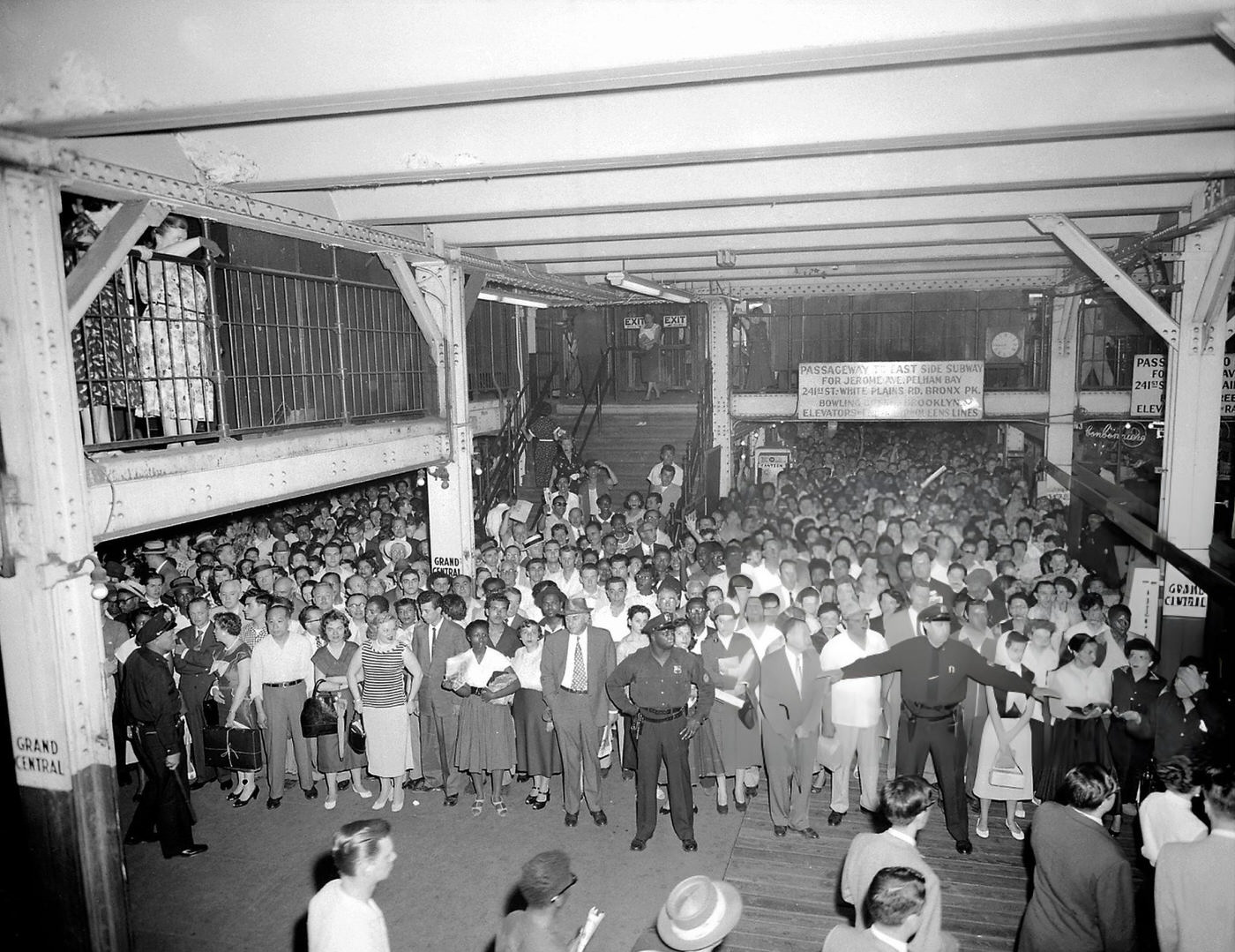

In the 1950s, the New York City subway was the city’s essential lifeline. It was a system in transition, moving from its pre-war origins into the modern era while facing new challenges from the automobile. For millions of New Yorkers, it was a non-negotiable part of daily life.

The Rider’s Experience

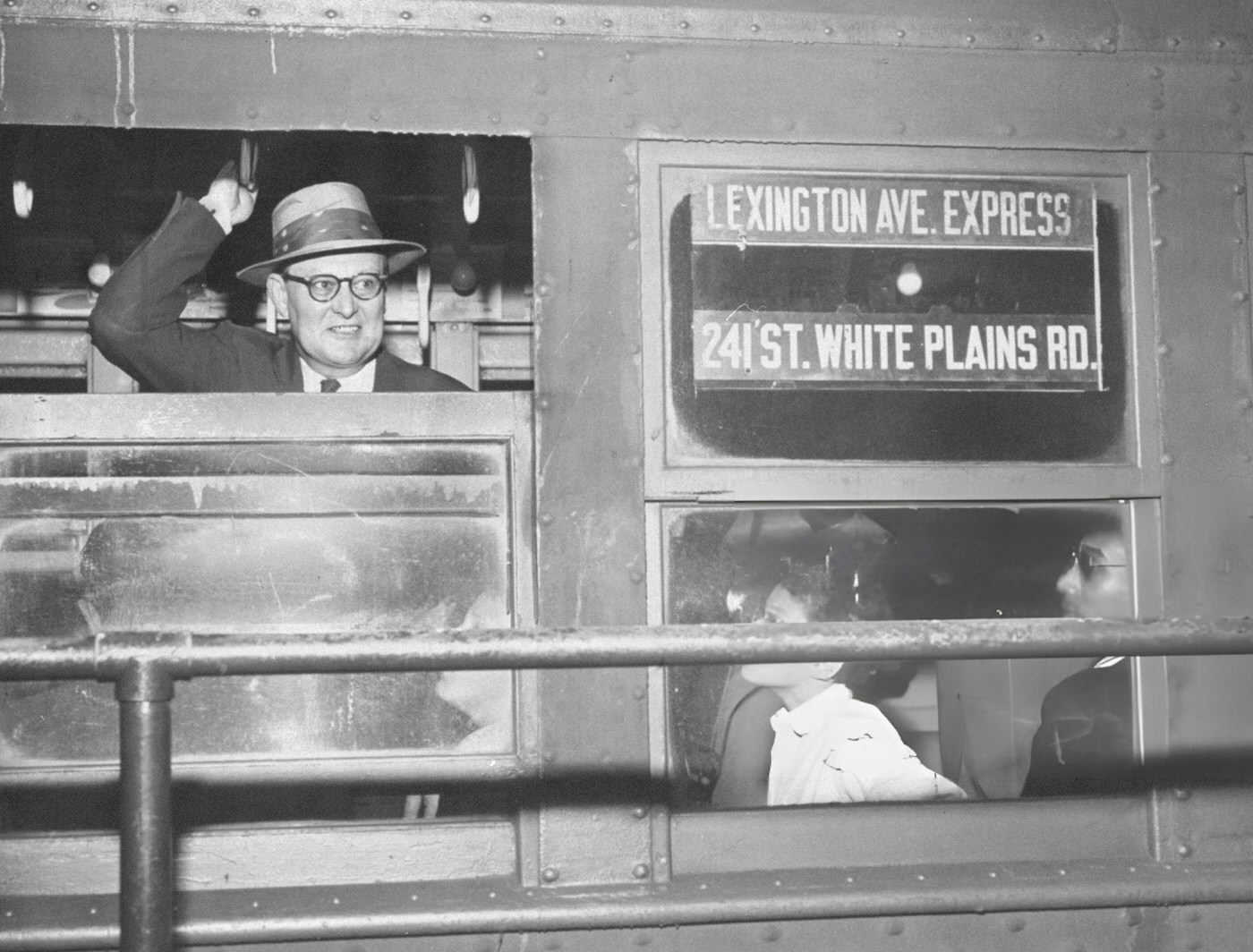

Boarding a subway car in the 1950s was an immersion into a world of noise and motion. The fleet was a mix of older, pre-war cars and newer models like the R16 cars, introduced in 1955. None of the cars were air-conditioned. In the summer, metal fans circulated hot, humid air through the crowded interiors. Windows were often slid open, bringing the roar of the tunnels directly into the car.

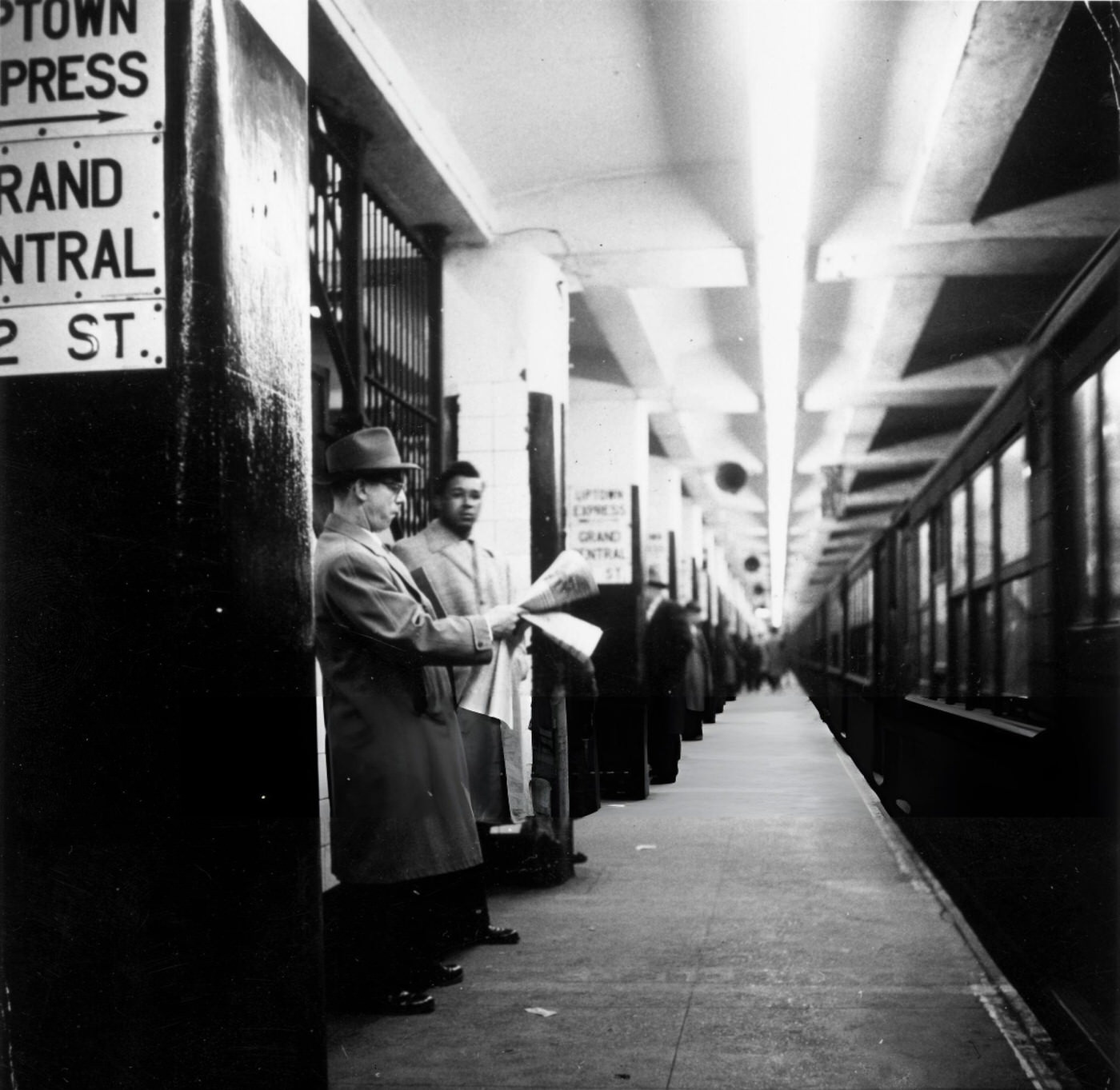

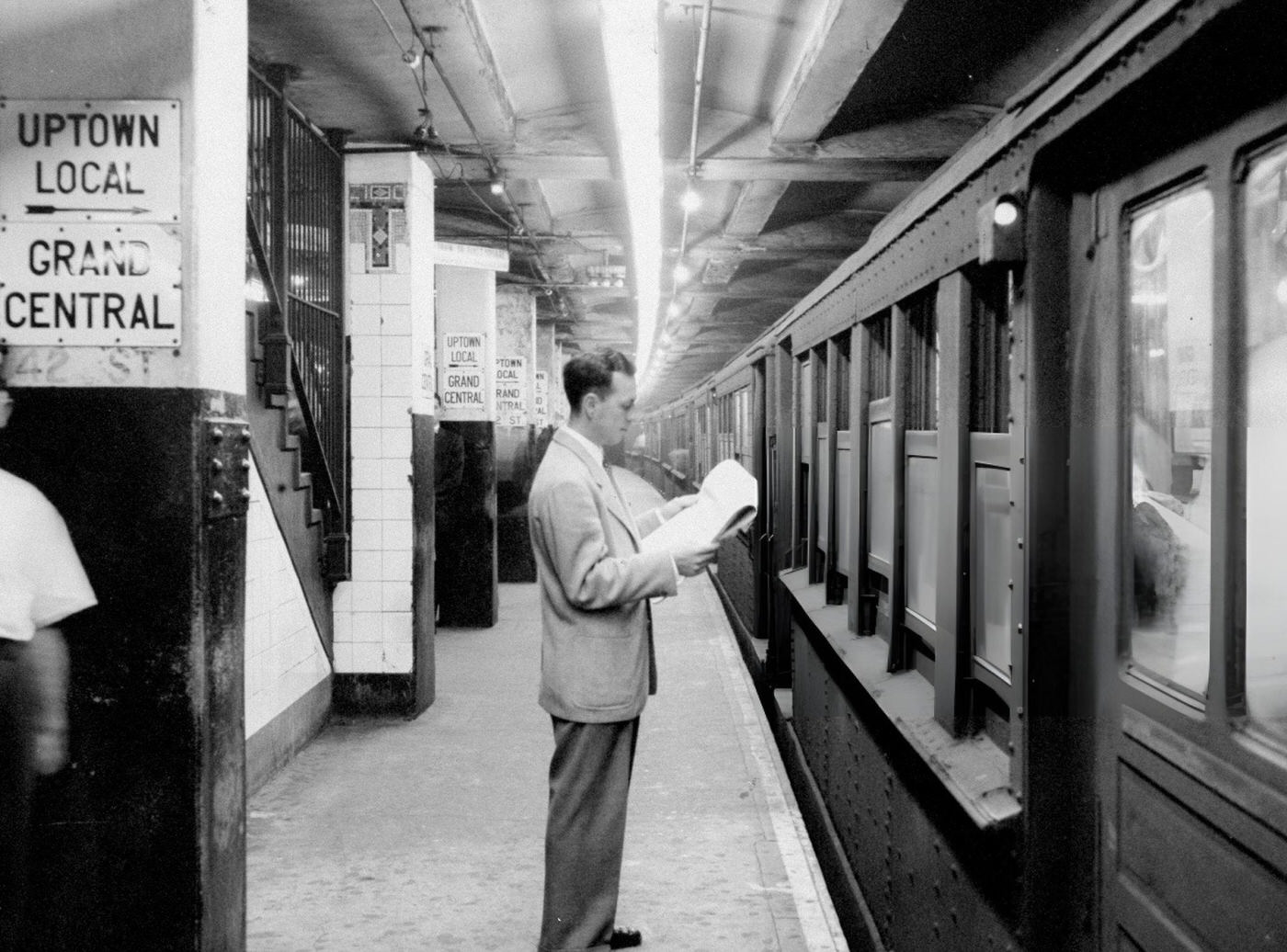

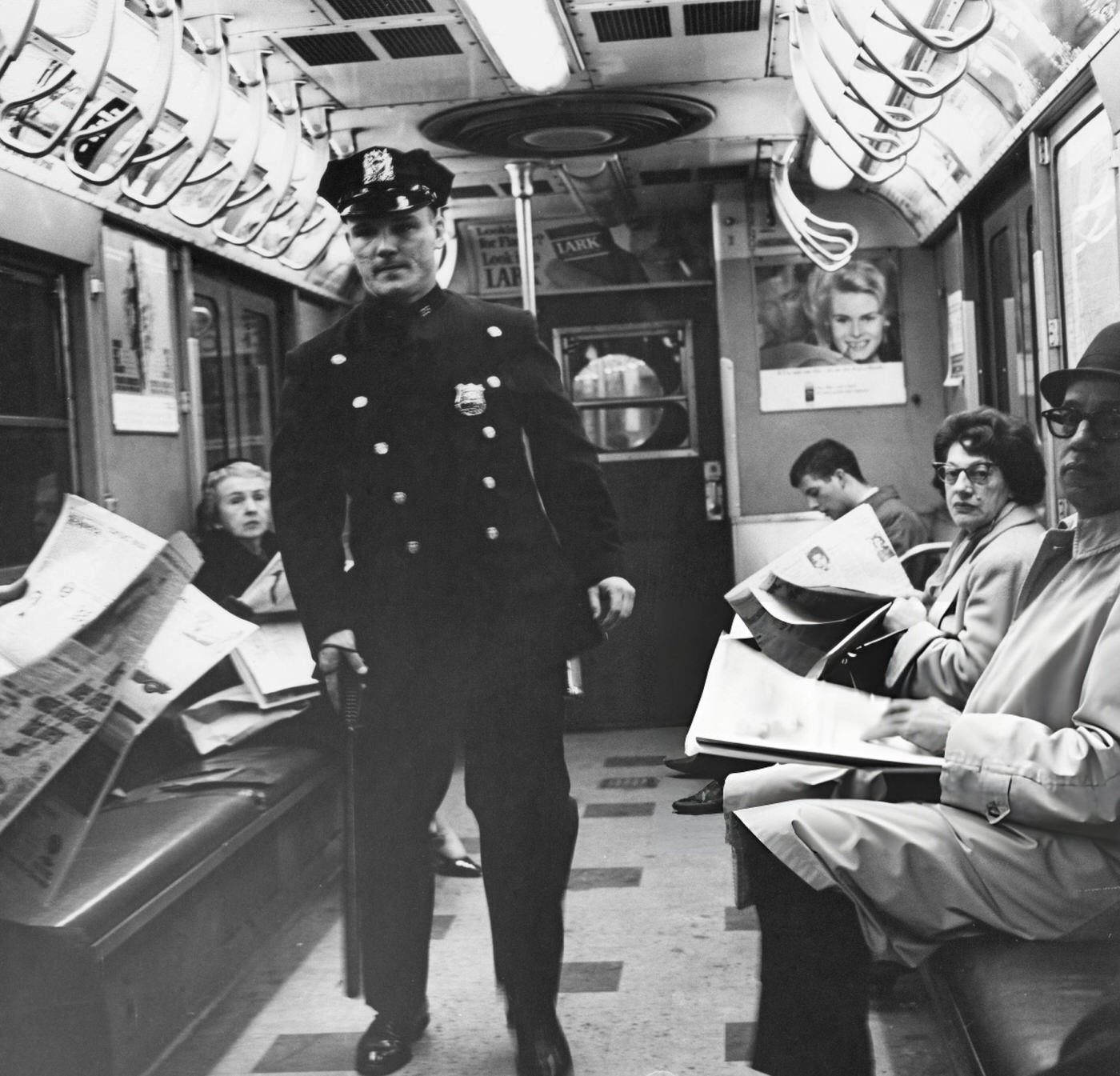

Commuters dressed more formally than today. Men in suits and hats filled the seats, reading broadsheet newspapers like the New York Times or tabloids like the Daily News. Women often wore dresses, hats, and gloves. The advertisements plastered inside the cars were for brands like Chesterfield cigarettes, Brylcreem hair styling products, and Coca-Cola.

Read more

A System Under New Management

The decade brought significant changes to how the subway operated. In 1953, control of the system was transferred from the city’s Board of Transportation to the newly created New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA).

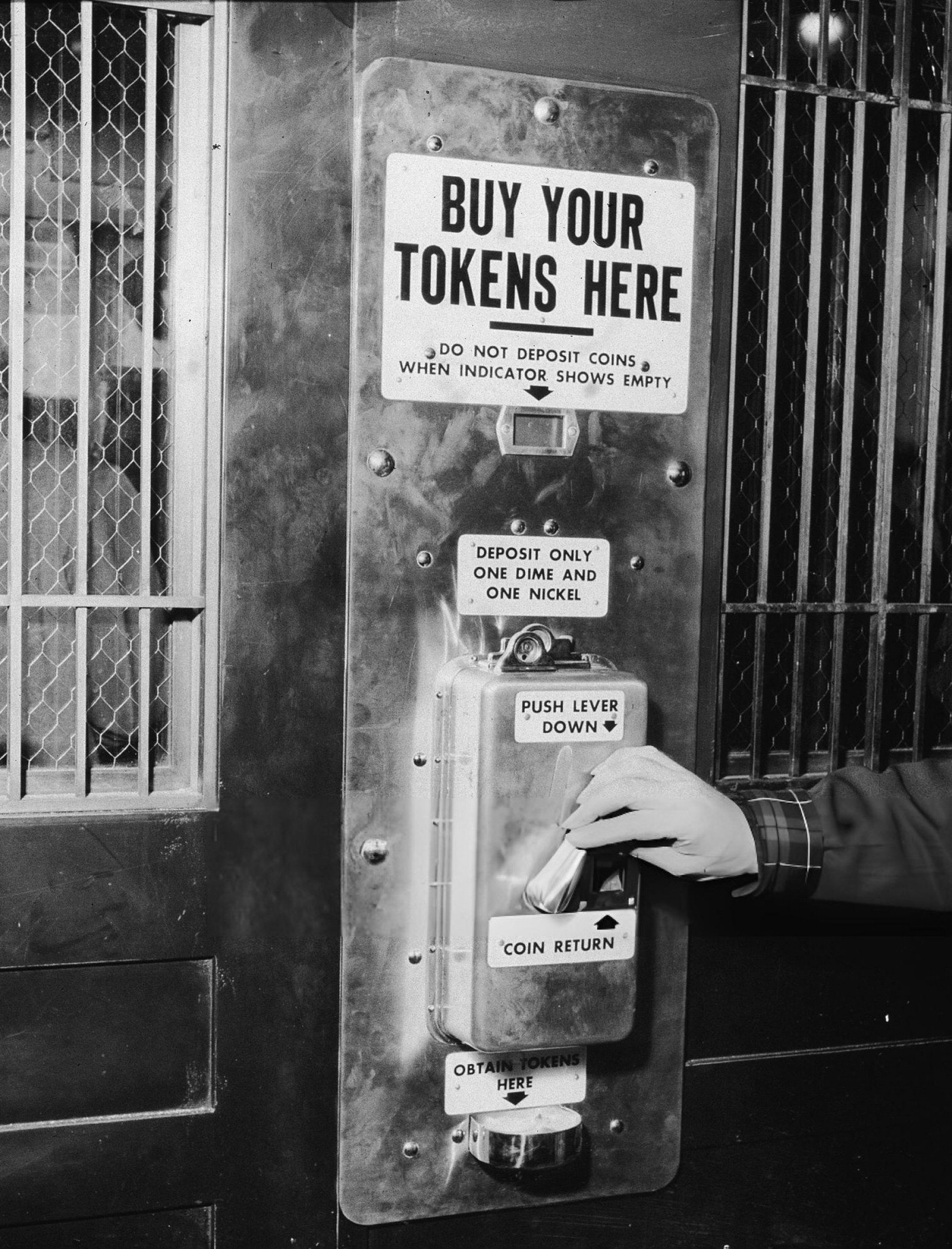

That same year, the iconic subway token was introduced. For the first time, riders used a small, coin-like object to pay their fare instead of dropping coins directly into the turnstile. The fare was raised from 10 to 15 cents to coincide with the token’s debut, a price that would hold for the next 13 years.

The Look of the Underground

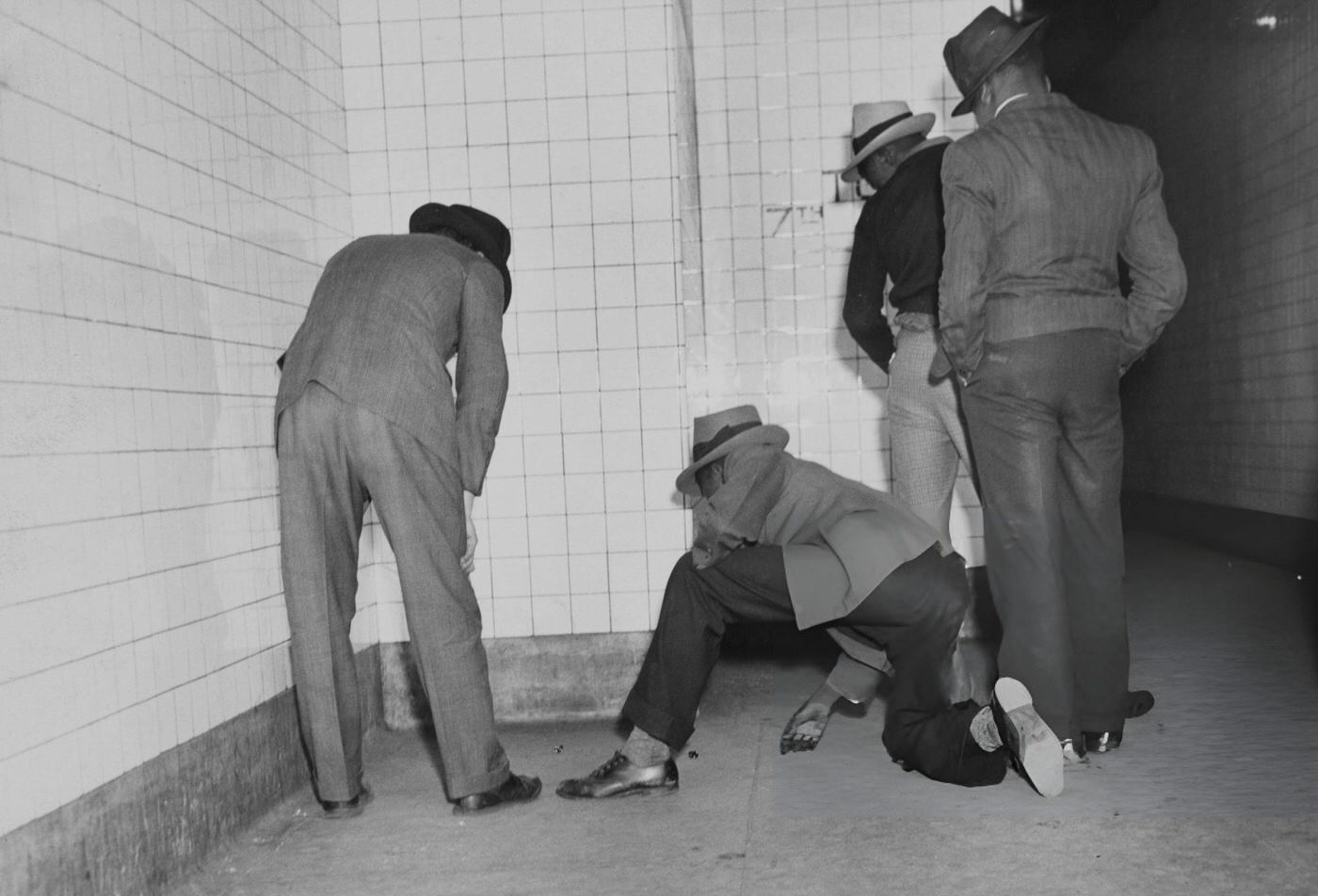

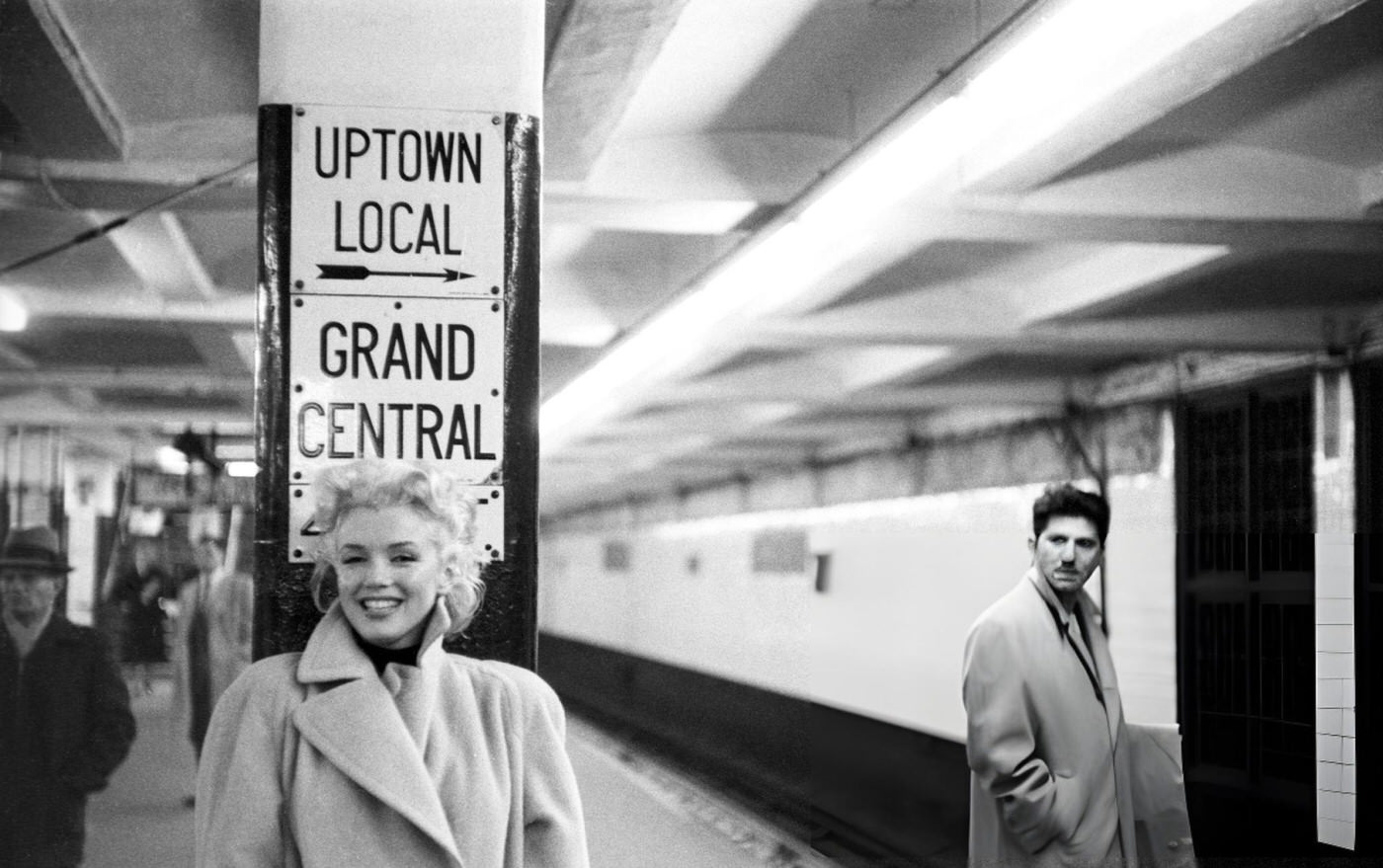

Stations in the 1950s retained much of their original design, with intricate tile mosaics spelling out station names. These underground spaces were often dimly lit compared to modern standards. The walls that were not covered in tile were plastered with posters for Broadway shows, movies, and consumer goods. While the system was not yet suffering from the widespread graffiti that would define later decades, it was aging, and signs of grime and wear were common.

The Rise of the Car and the Fall of the ‘El’

While the subway remained dominant, the 1950s saw the beginning of a decline in ridership. The post-war economic boom put automobiles within reach of more families, and the city’s focus shifted to building highways and parkways. This new competition for commuters marked a turning point for the transit system.

The most visible sign of this shift was the demolition of elevated train lines, known as “Els.” In 1955, the Third Avenue Elevated line in Manhattan, a fixture of the city since 1878, was dismantled. Its removal dramatically changed the streetscape of the East Side, letting sunlight reach blocks that had been in shadow for decades and signaling a move away from elevated tracks in favor of underground tunnels.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings