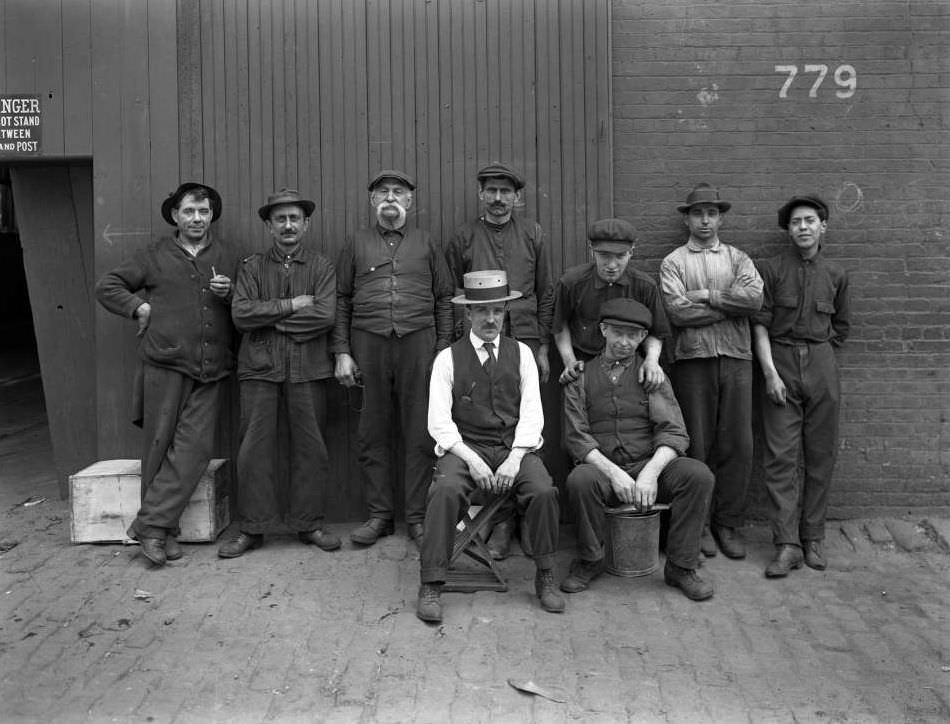

In the first decades of the 20th century, New York City was a powerhouse of industry and construction, and its engine was a vast and diverse army of workers. From the crowded garment sweatshops of the Lower East Side to the dangerous construction sites of new skyscrapers, millions of men and women performed the demanding physical and clerical labor that kept the metropolis running.

The single largest industry was the manufacturing of clothing. In thousands of small, crowded workshops known as sweatshops, a workforce composed largely of young Jewish and Italian immigrant women toiled for long hours. They worked on a “piece-work” system, meaning they were paid for each item they completed, not by the hour. A typical workday was 12 hours or more, six days a week, in poorly lit and badly ventilated rooms filled with the roar of sewing machines. The dangers of these conditions were made horrifically clear by the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911, where 146 workers, mostly young women, died because of locked doors and inadequate fire escapes.

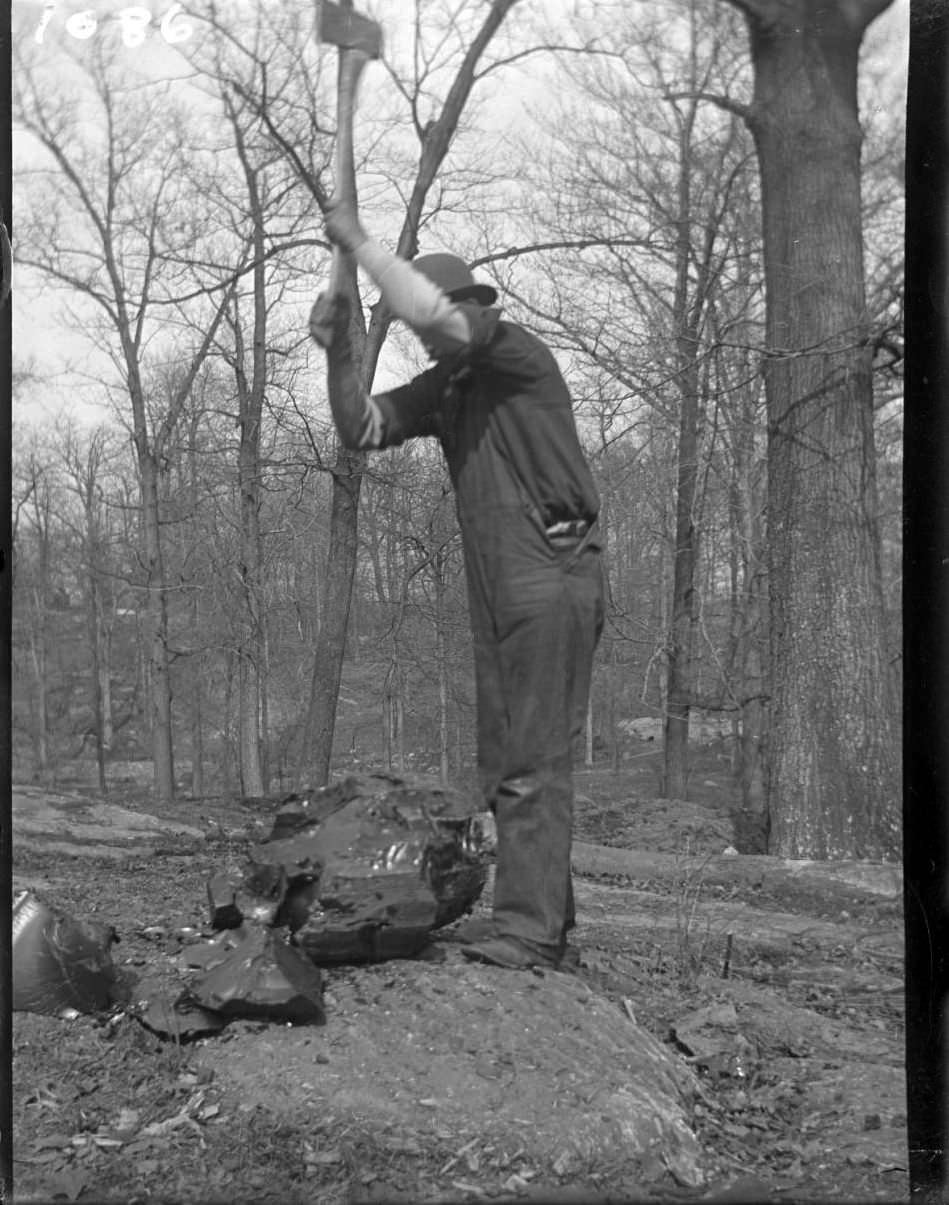

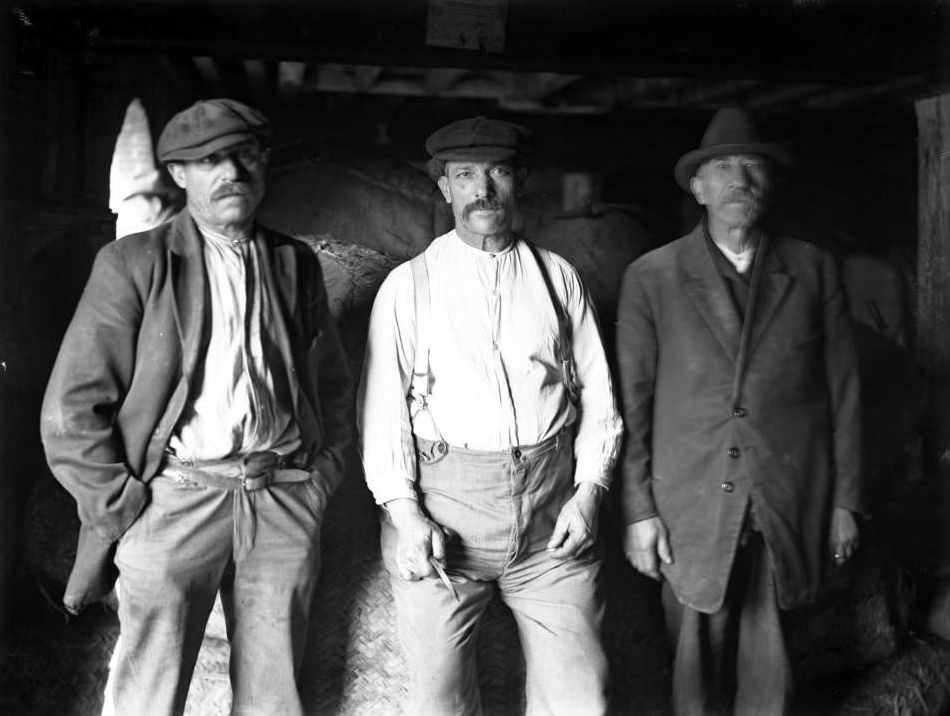

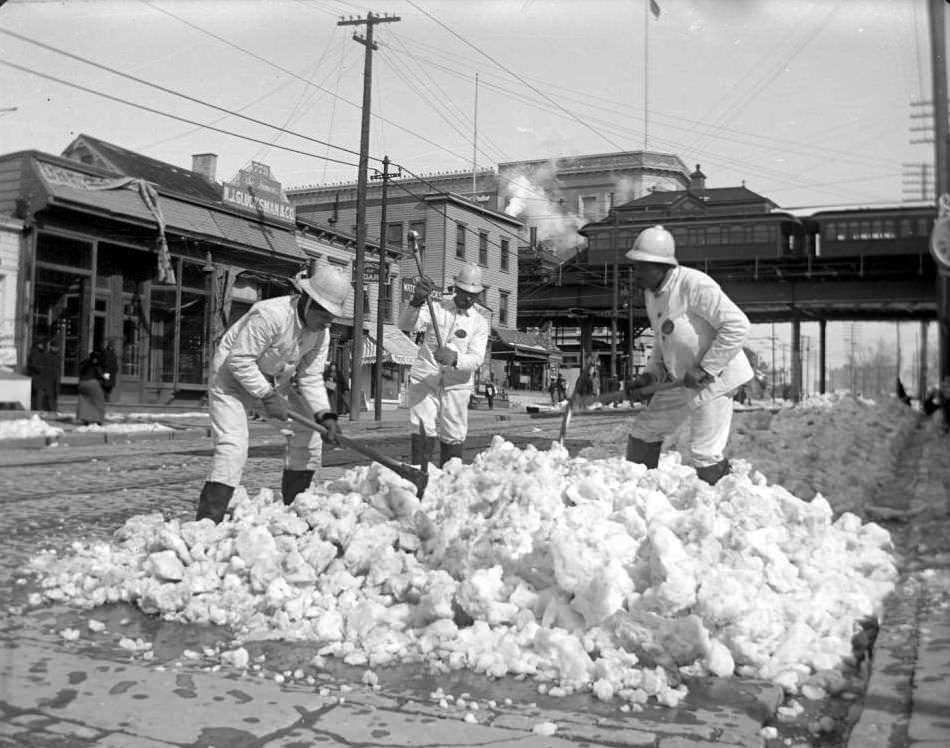

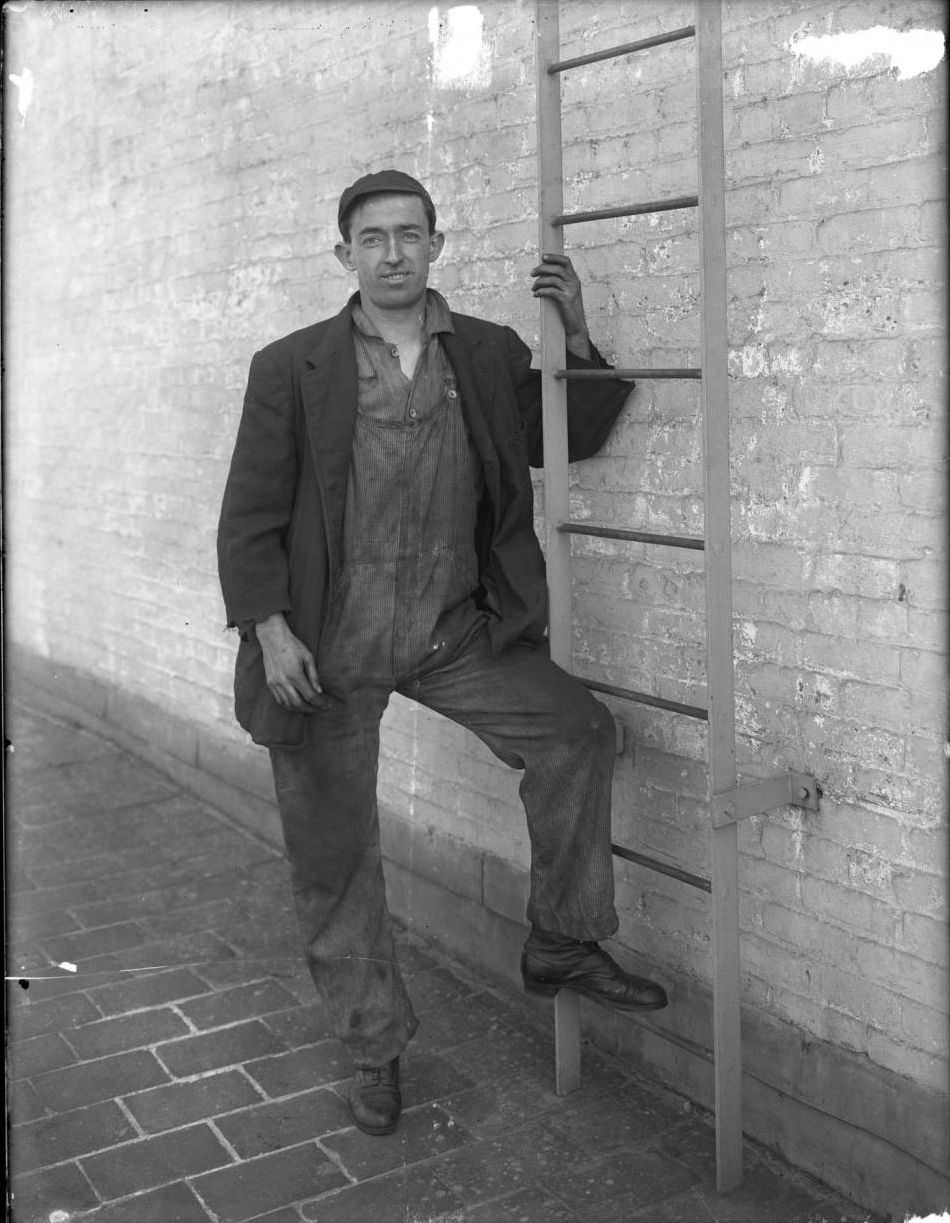

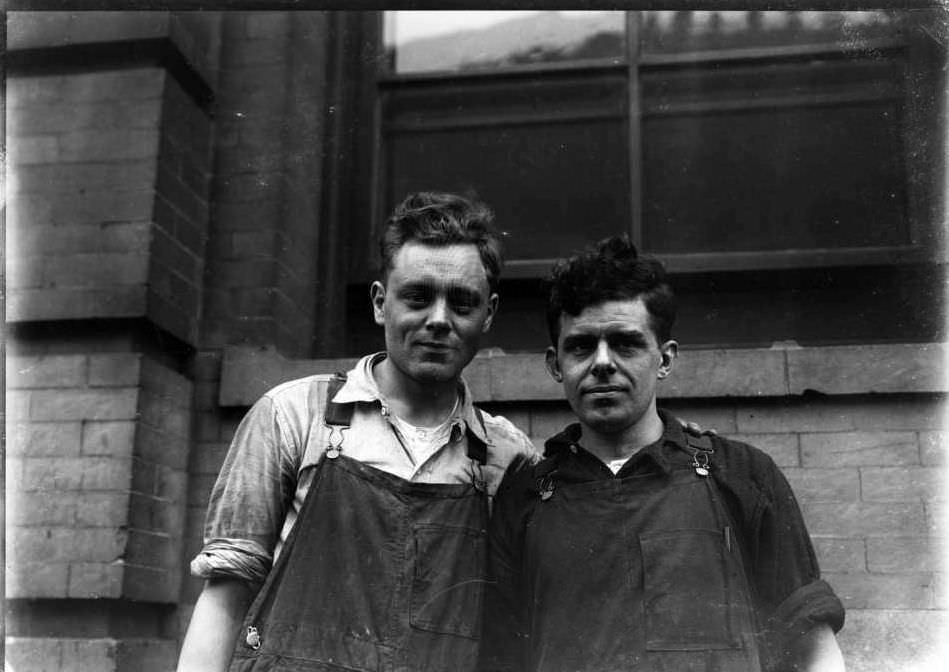

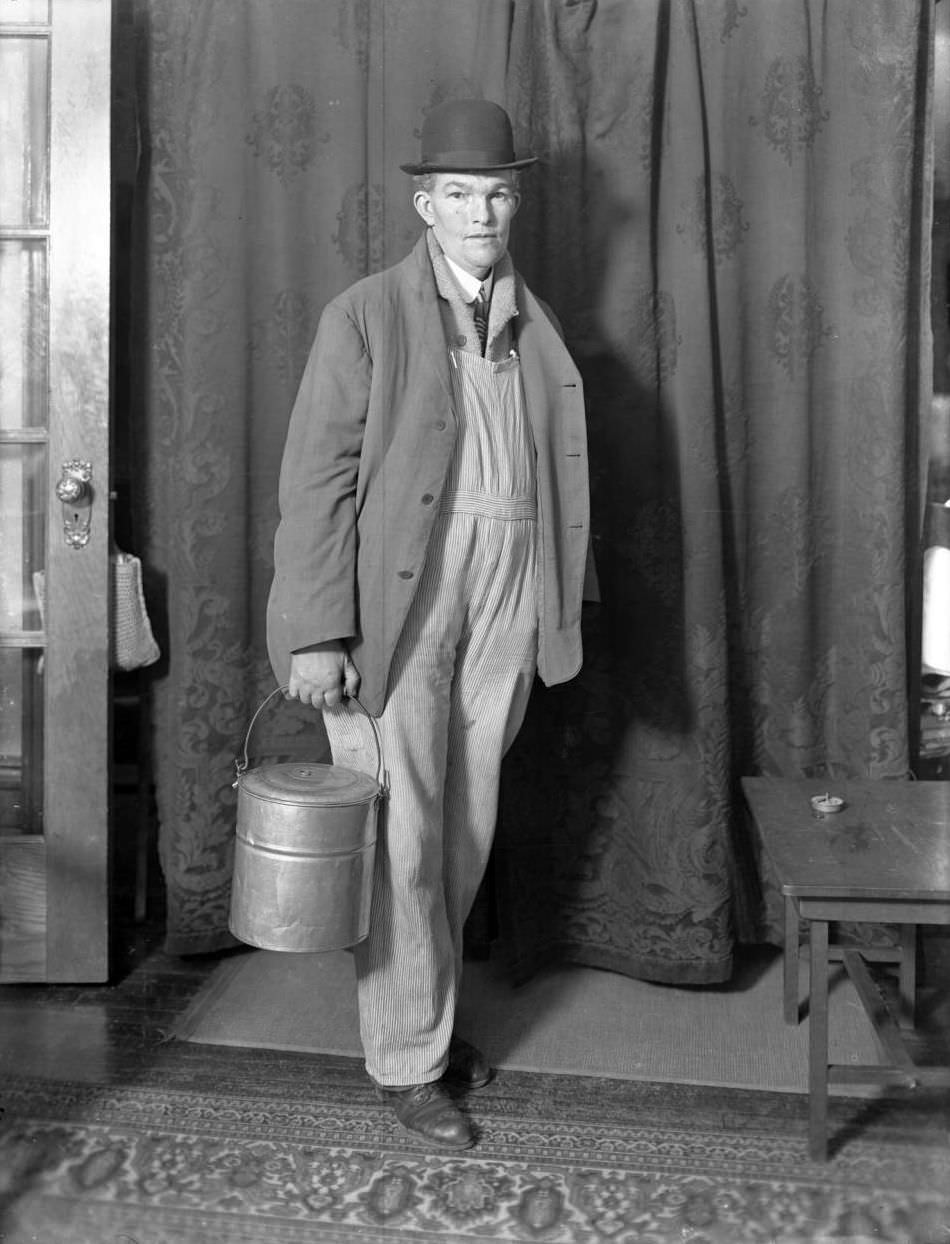

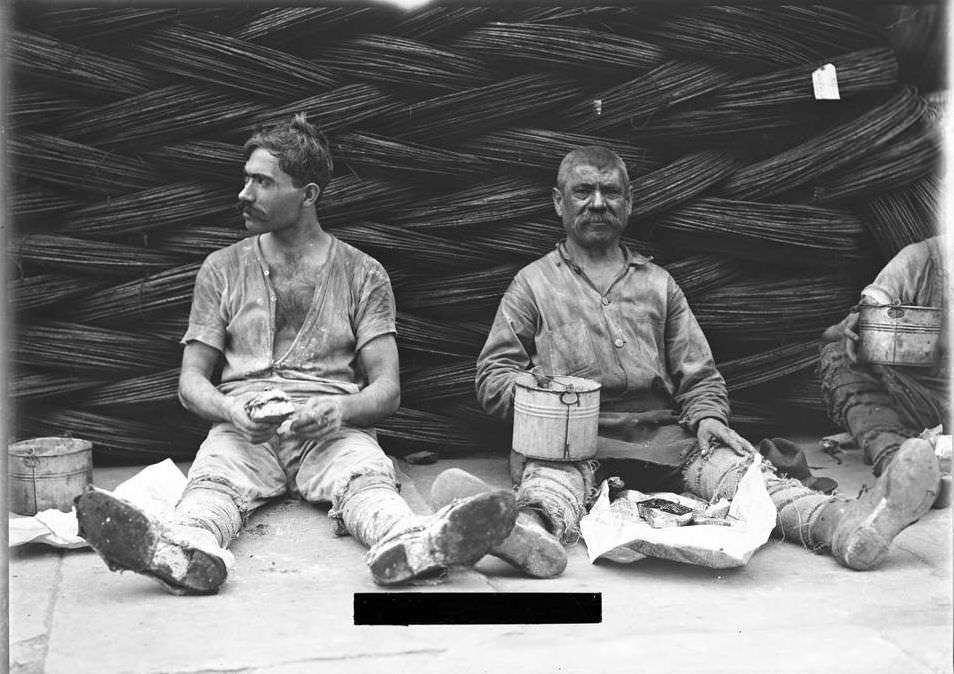

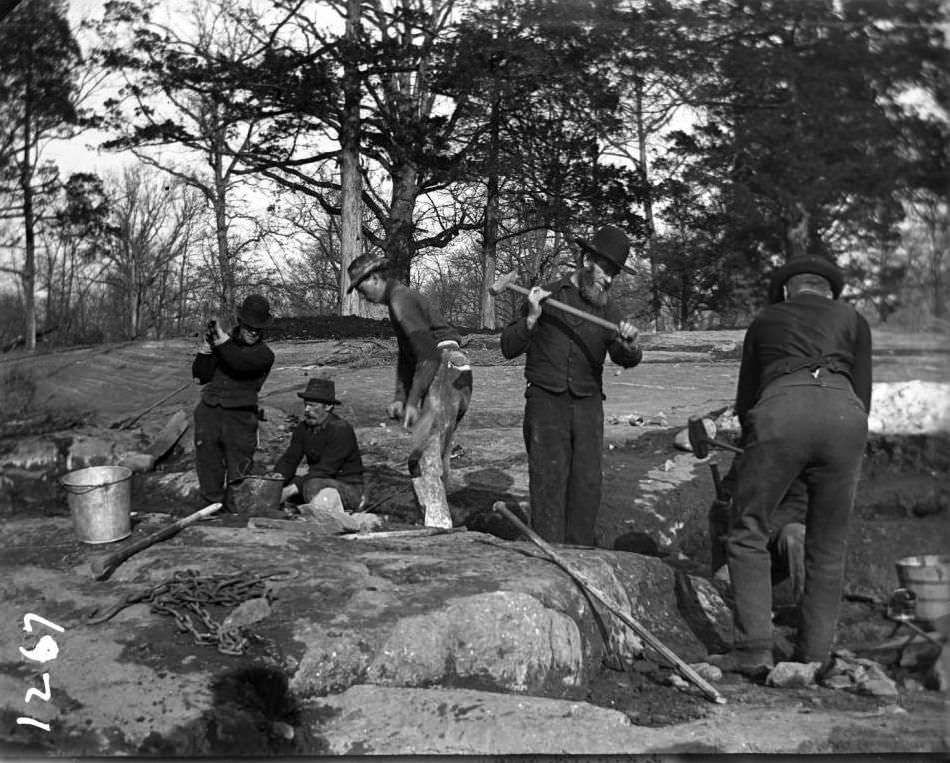

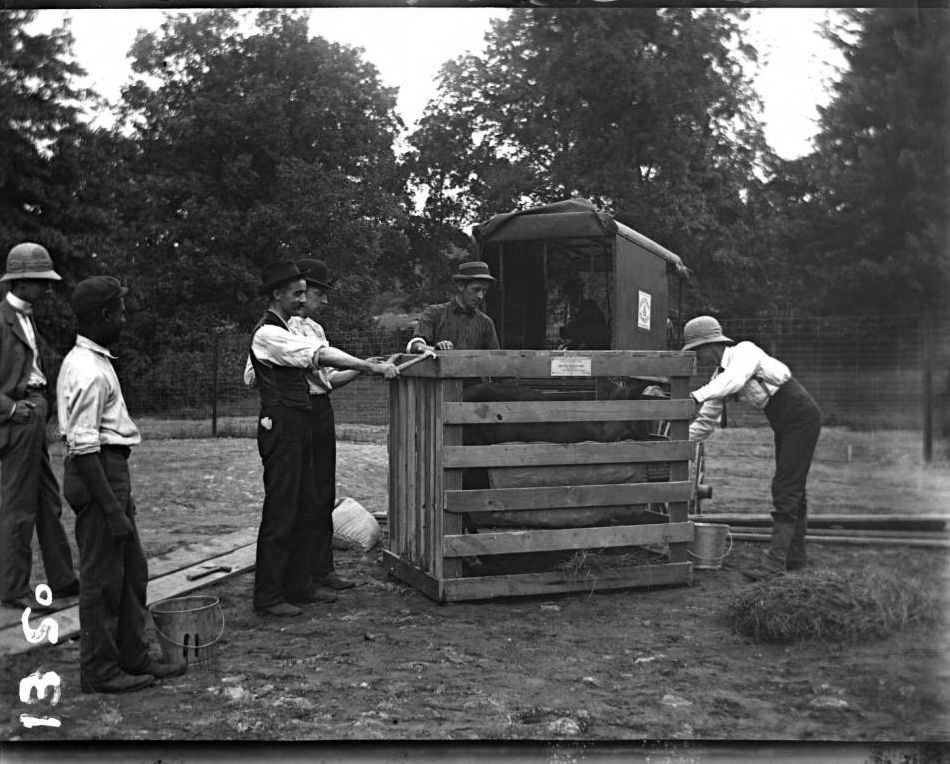

The city’s rapid physical growth was made possible by an army of construction and manual laborers. Teams of “sandhogs,” many of them Irish immigrants, worked under immense pressure in compressed air chambers to dig the new subway and railroad tunnels under the East and Hudson Rivers. High above the city, ironworkers, including many Mohawk men, walked across narrow steel beams with no safety harnesses, riveting together the skeletons of the city’s first skyscrapers. On the streets, laborers paved roads, laid trolley tracks, and dug foundations.

Read more

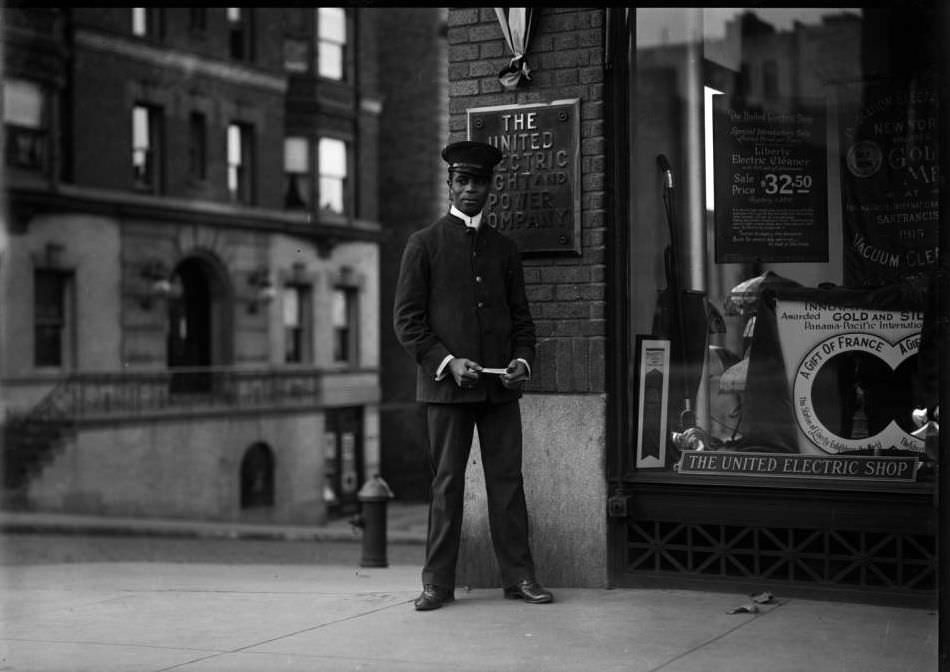

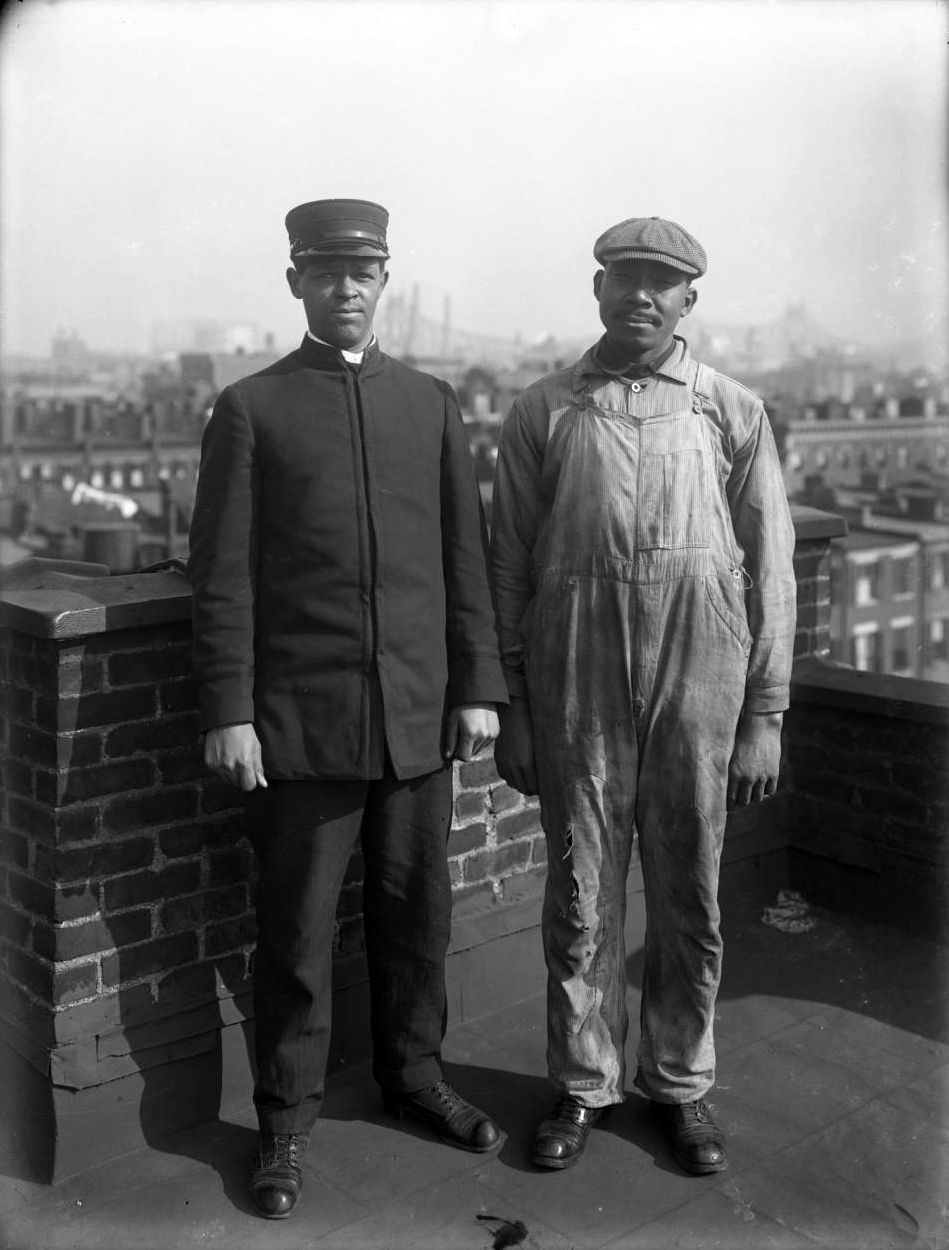

A huge number of New Yorkers, primarily women, worked in domestic and service roles. In the grand homes of the wealthy and the apartments of the middle class, Irish and African American women worked as maids, cooks, and nannies. In the city’s new luxury hotels and department stores, thousands more worked as elevator operators, hotel maids, and salesclerks, the latter of whom spent long shifts standing on their feet for low wages. A new and rapidly growing field for young women was work as a telephone operator, connecting calls on massive switchboards.

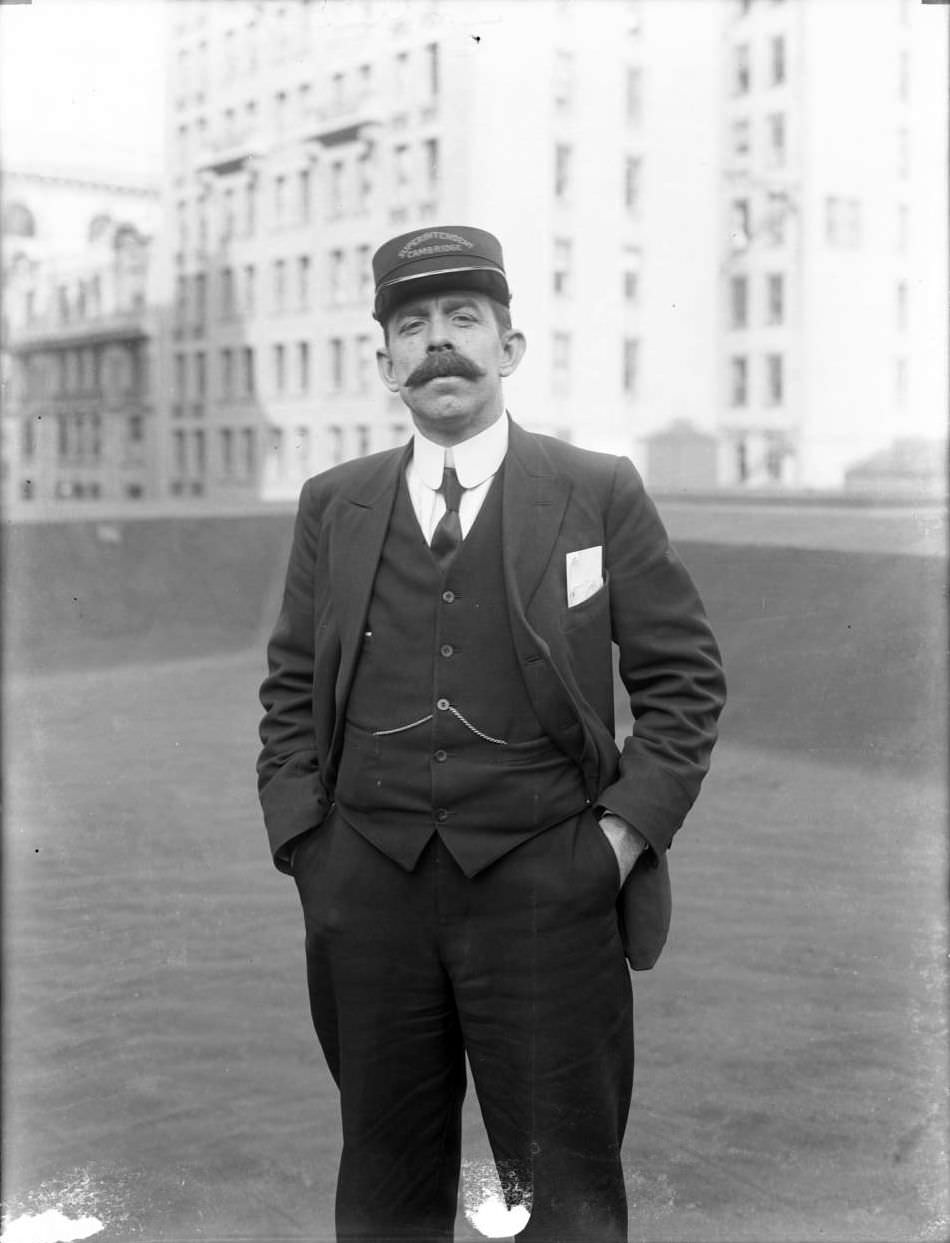

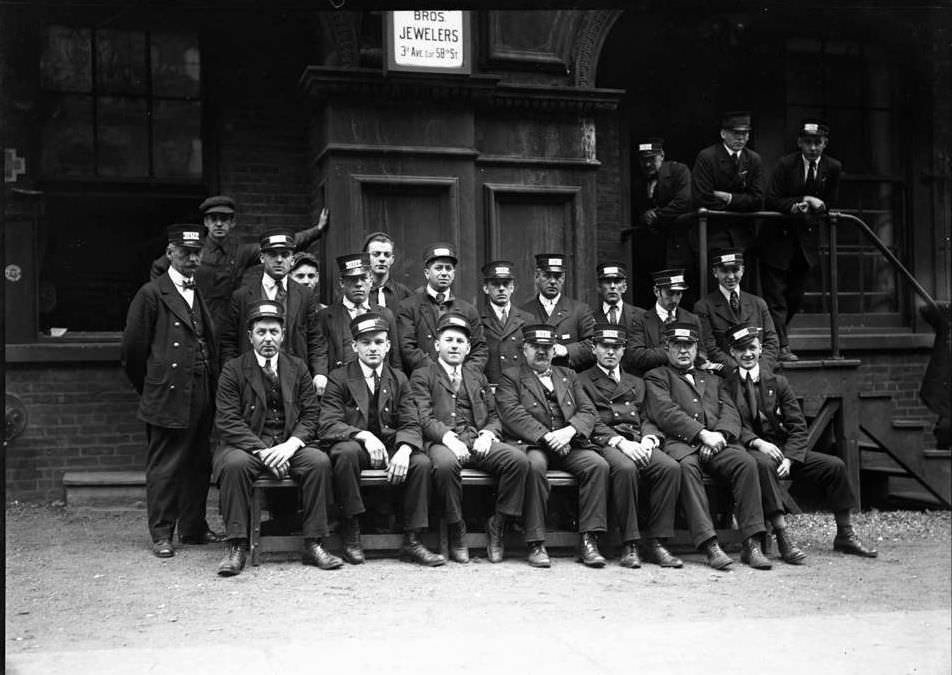

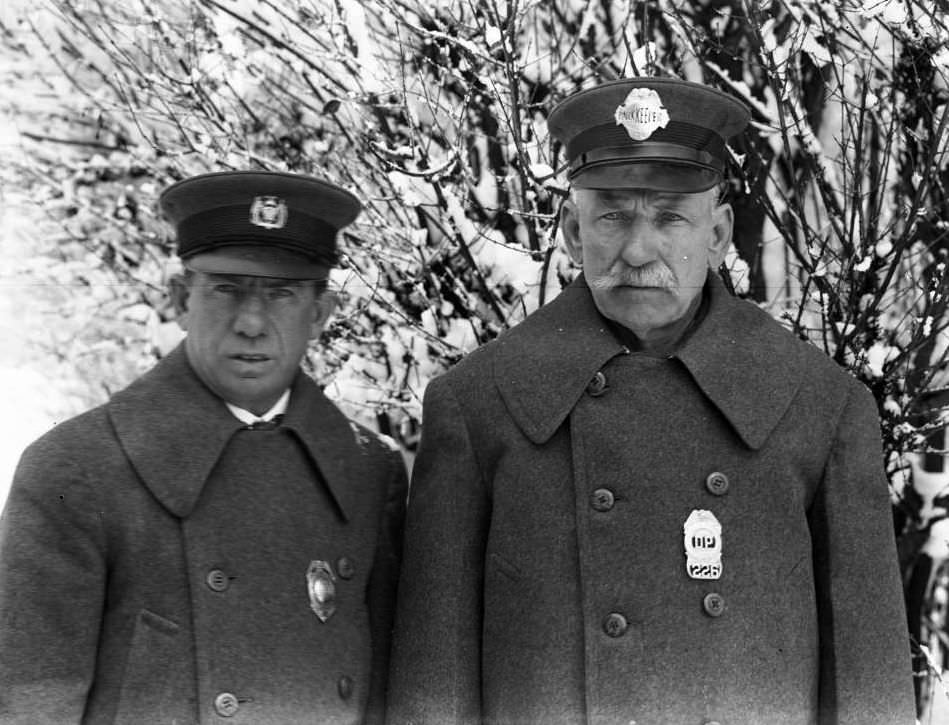

The city’s busy port and transportation network required another massive workforce. Along the piers of the Hudson and East Rivers, longshoremen performed the back-breaking work of loading and unloading cargo from ships, using hand trucks and brute strength. The new subway and elevated train lines were operated by motormen and conductors, while the streets were still filled with teamsters driving horse-drawn delivery wagons, their work just beginning to compete with the first motorized trucks.

A growing class of white-collar workers filled the city’s offices. Men worked as clerks and bookkeepers, while the new profession of stenographer or typist was seen as a respectable job for unmarried women. These workers put in long hours in large, open offices, documenting the transactions of the city’s booming economy.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings