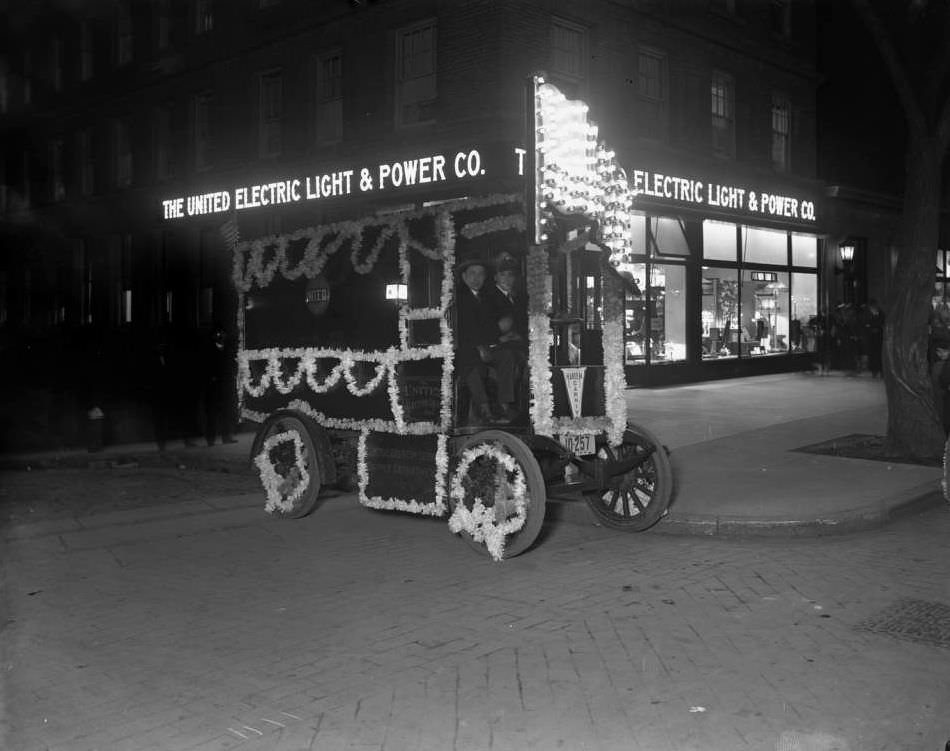

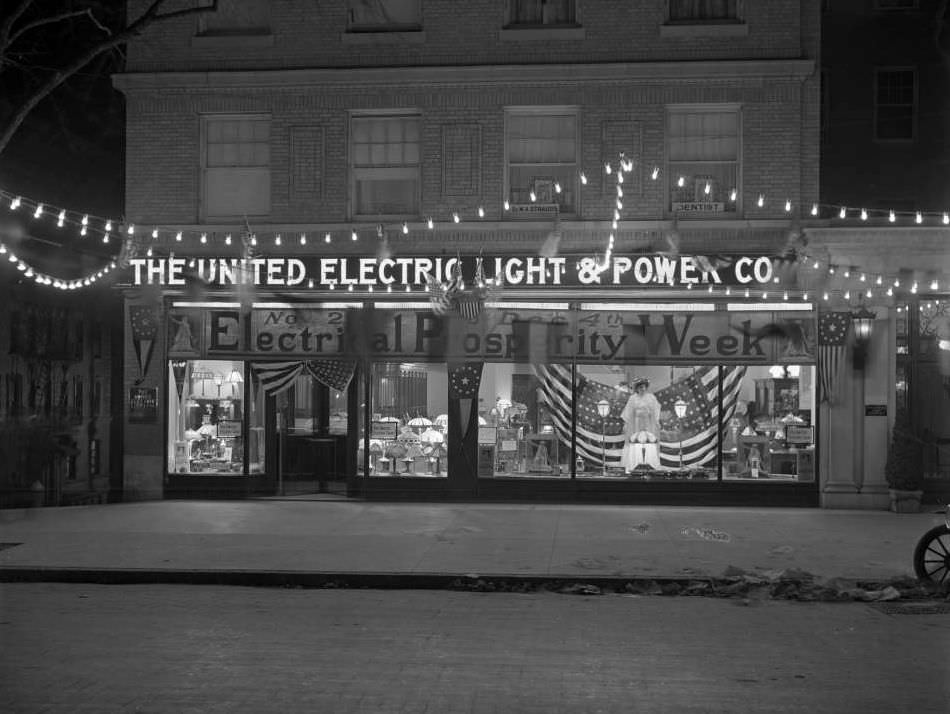

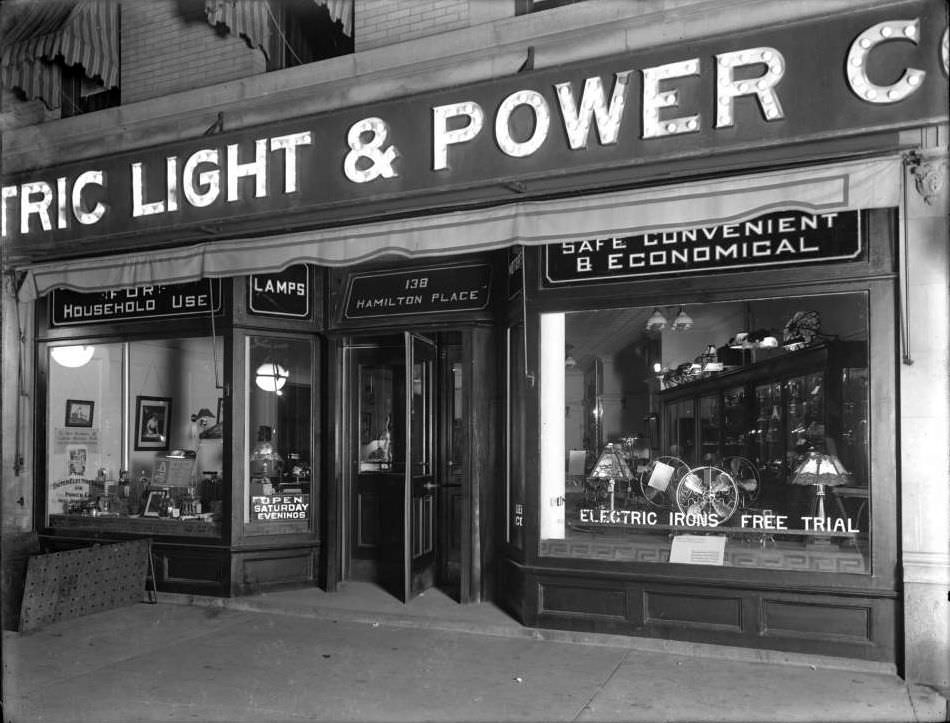

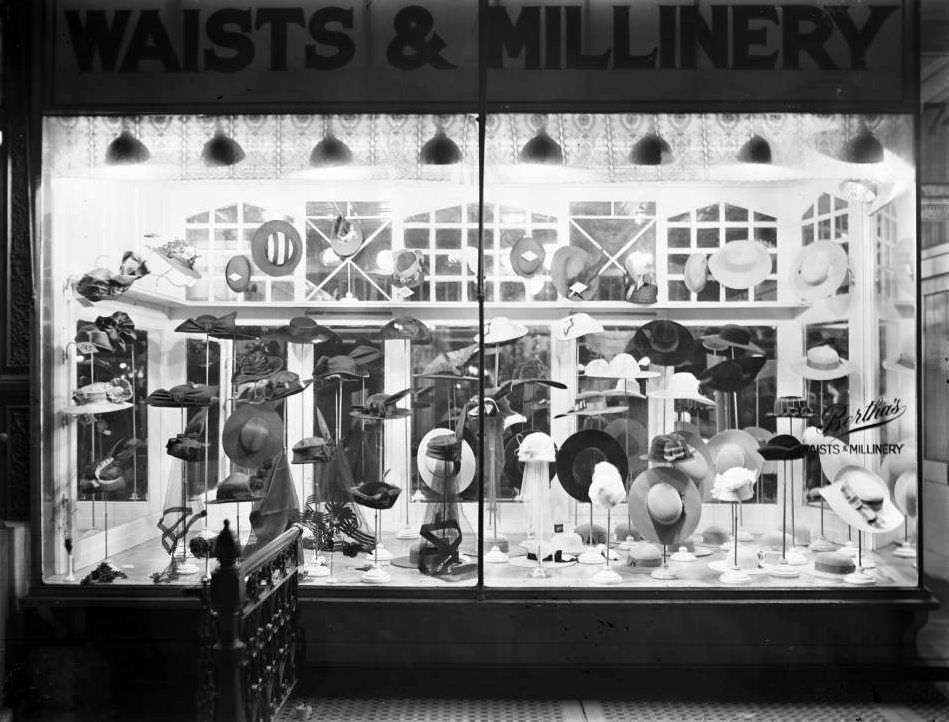

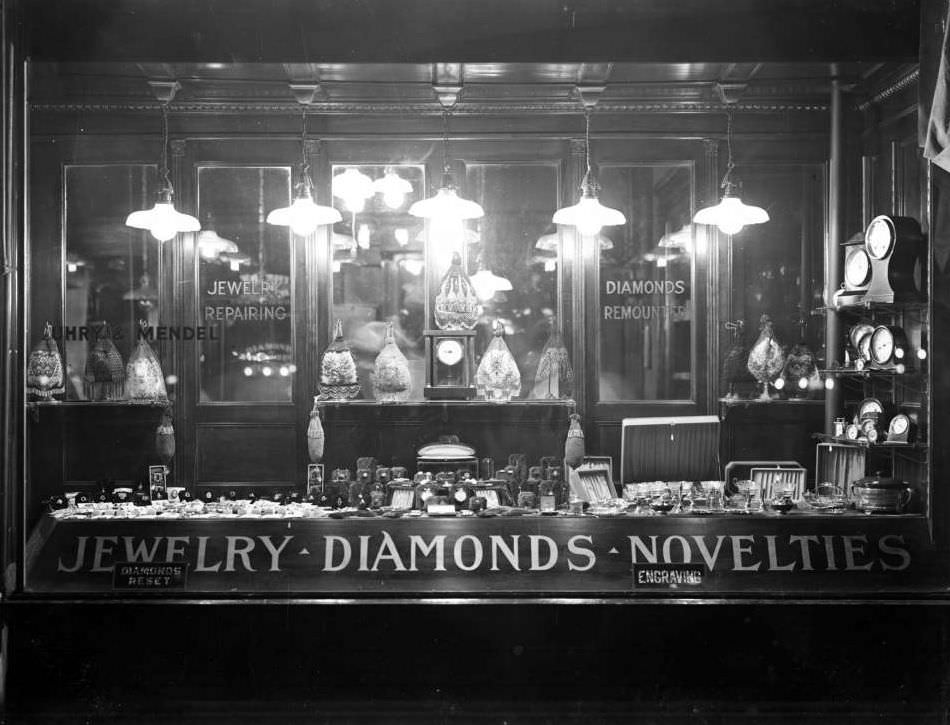

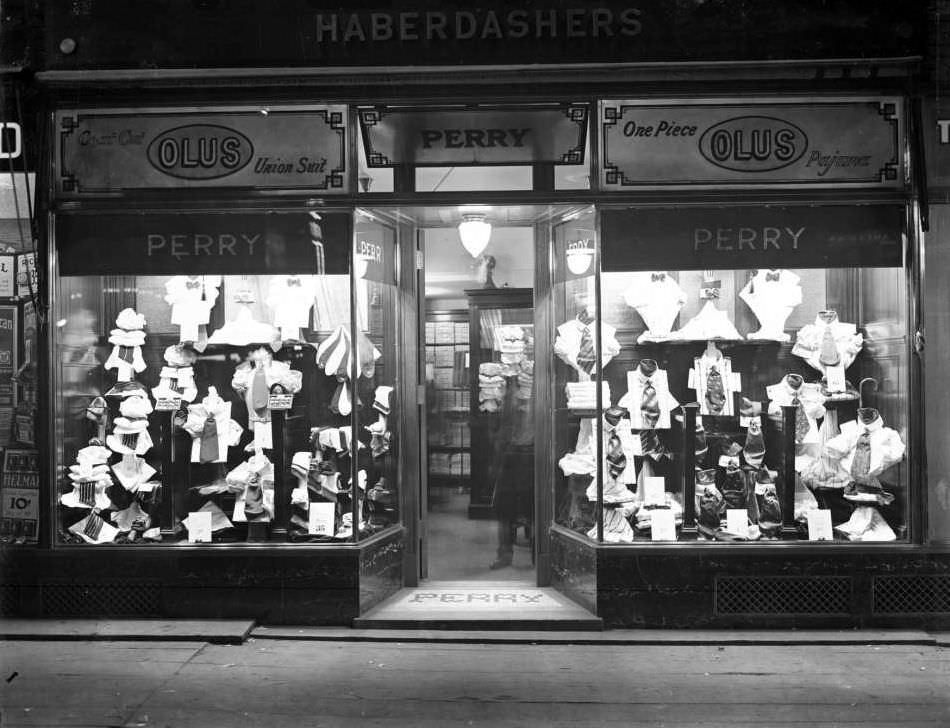

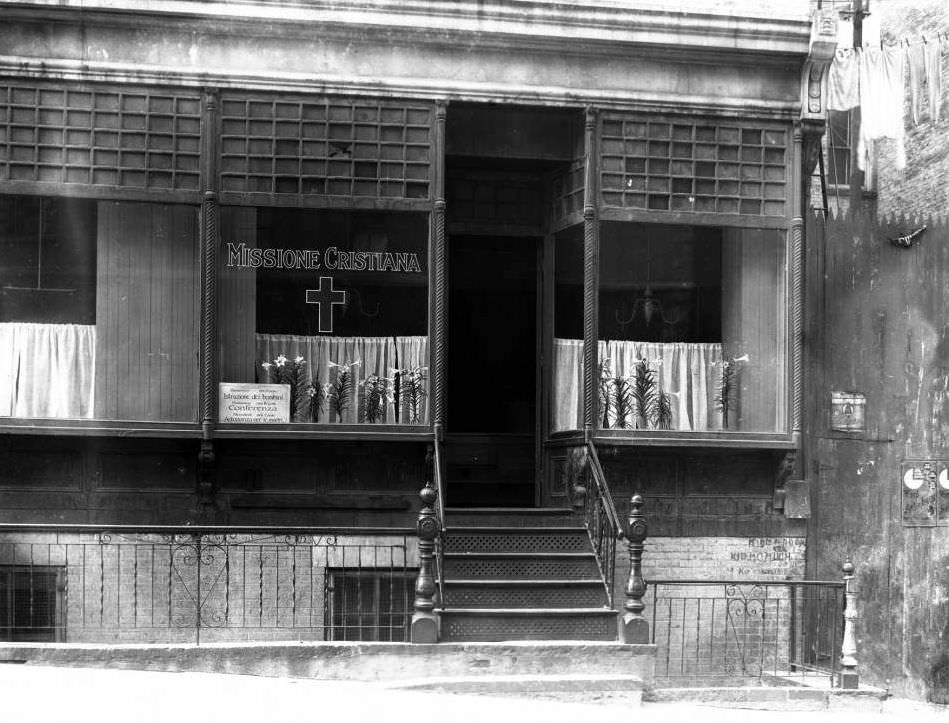

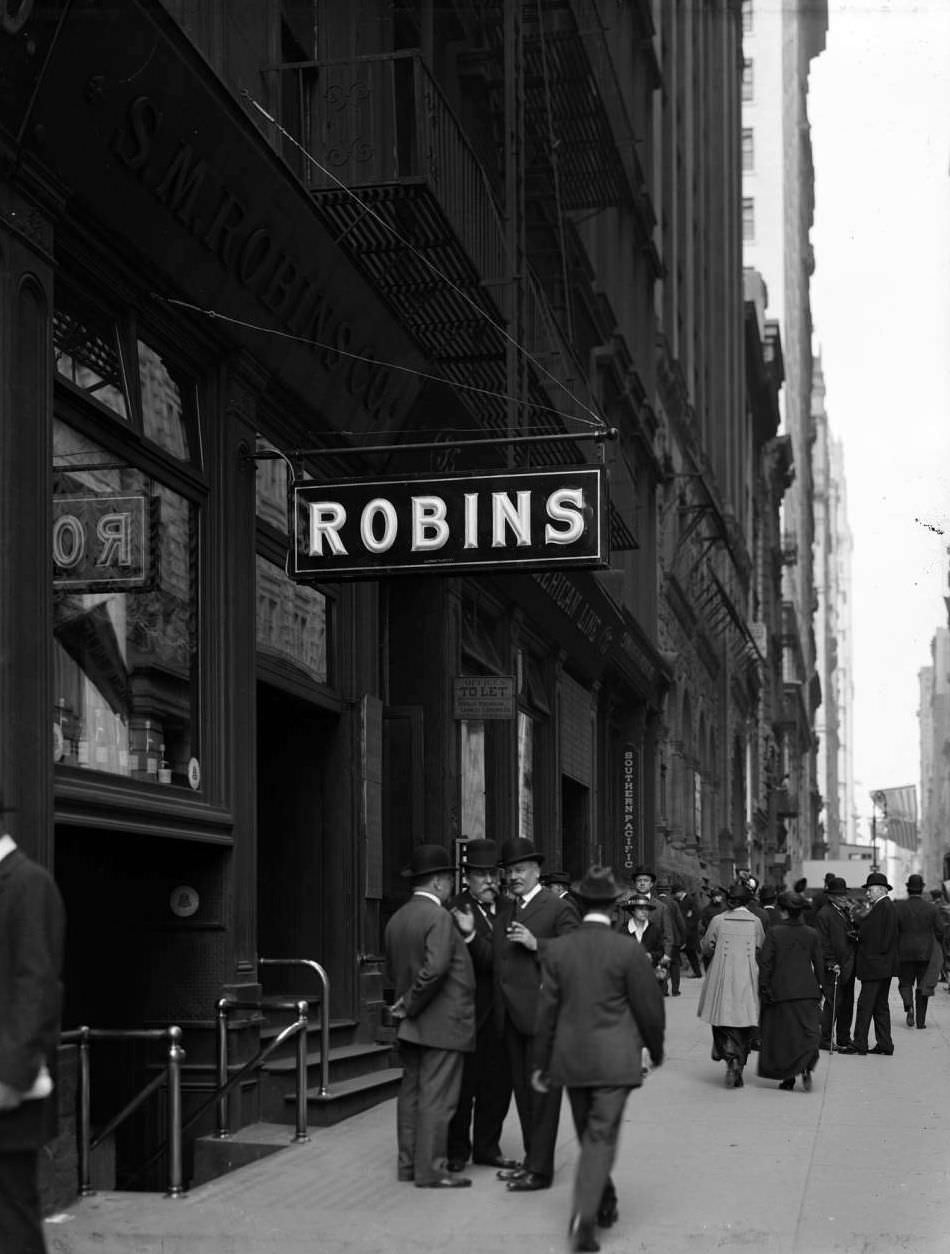

In the New York City of the early 1900s, the character of a neighborhood was written on its storefronts. From the polished marble of Fifth Avenue to the crowded pavement of the Lower East Side, the city’s shops presented a diverse and detailed face to the public. These were more than just entrances to businesses; they were carefully designed displays of craft, commerce, and community.

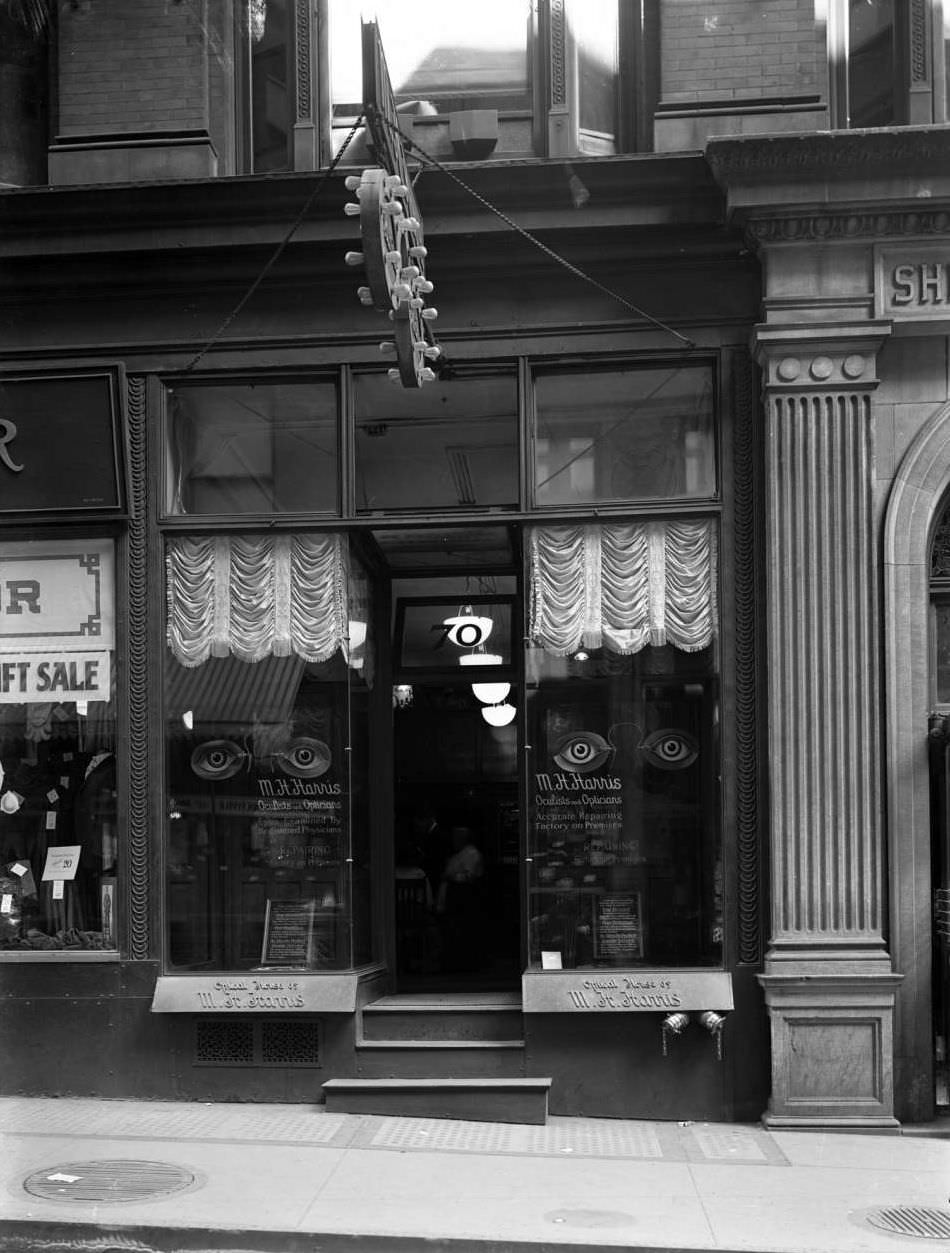

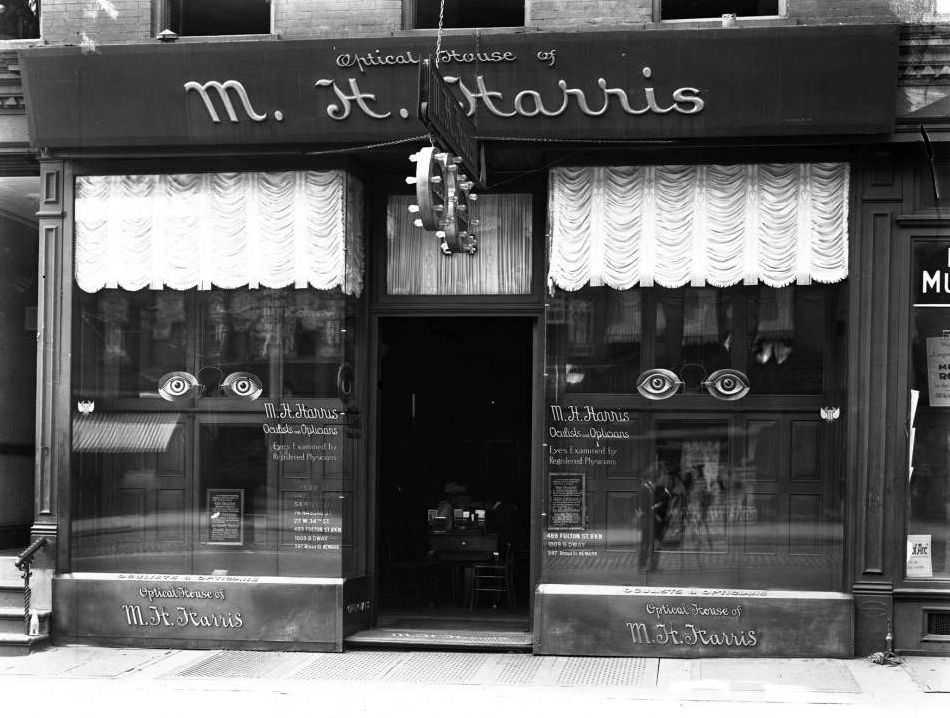

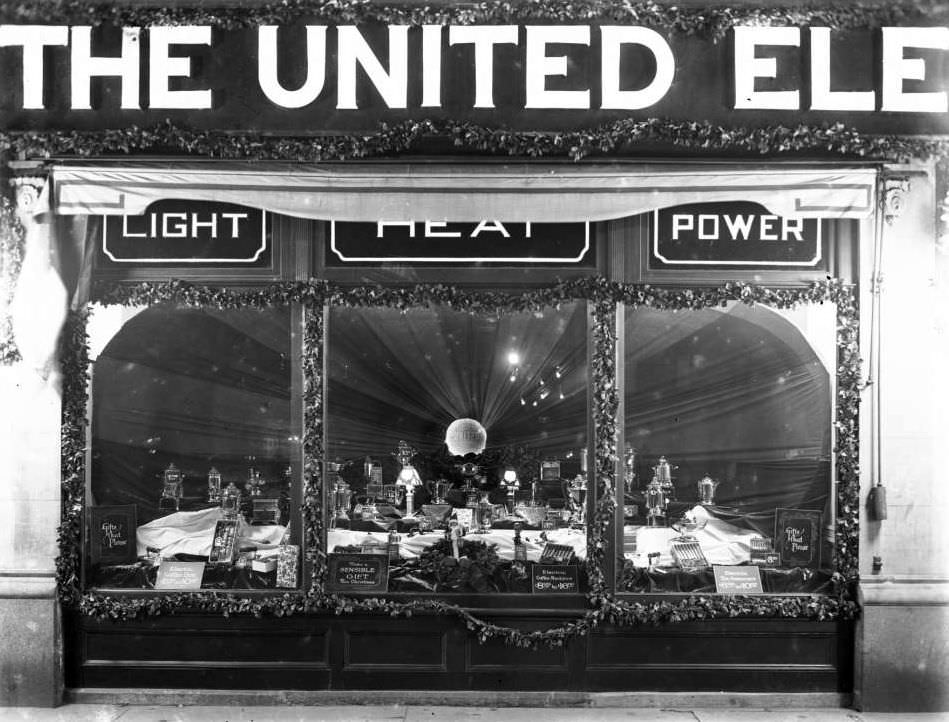

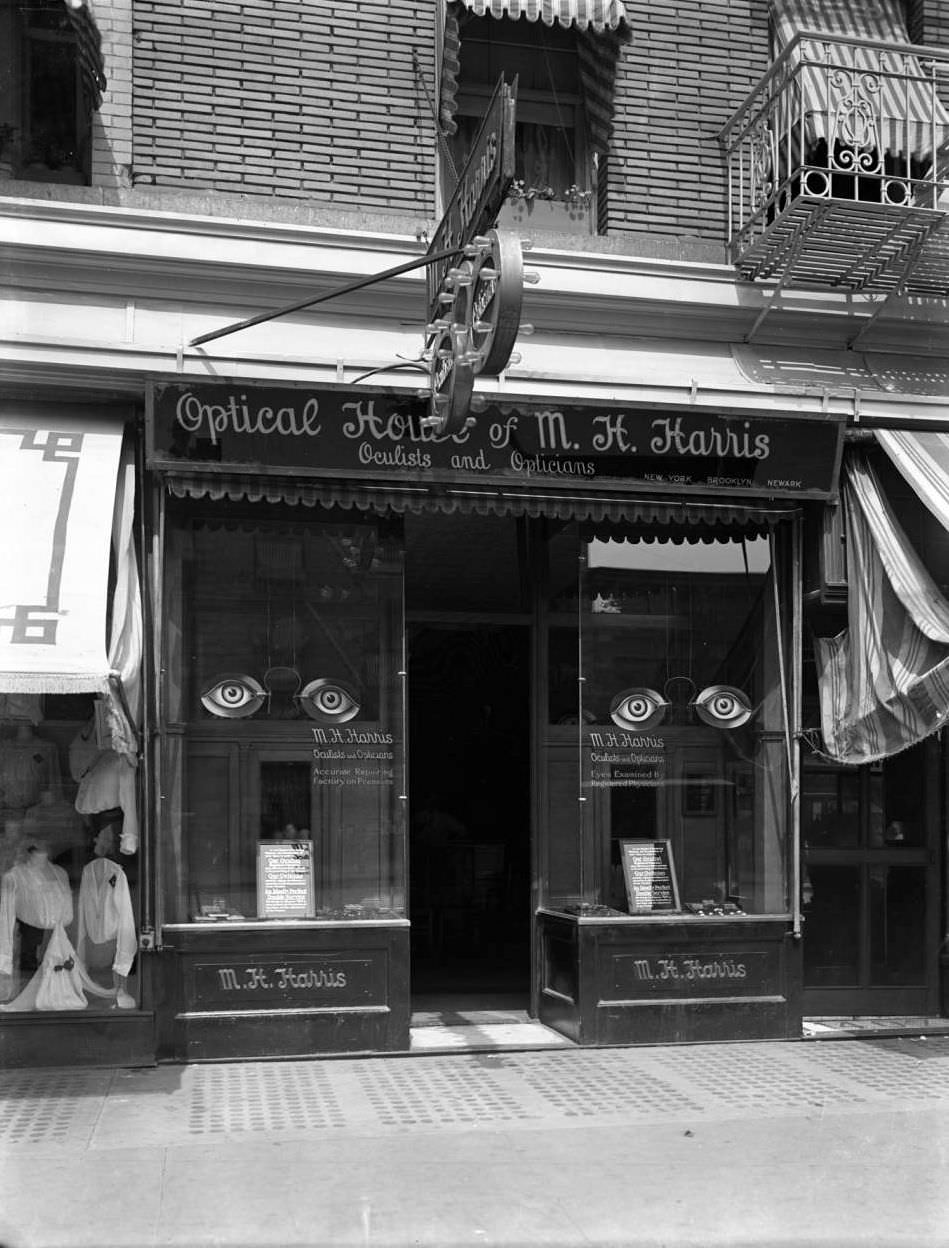

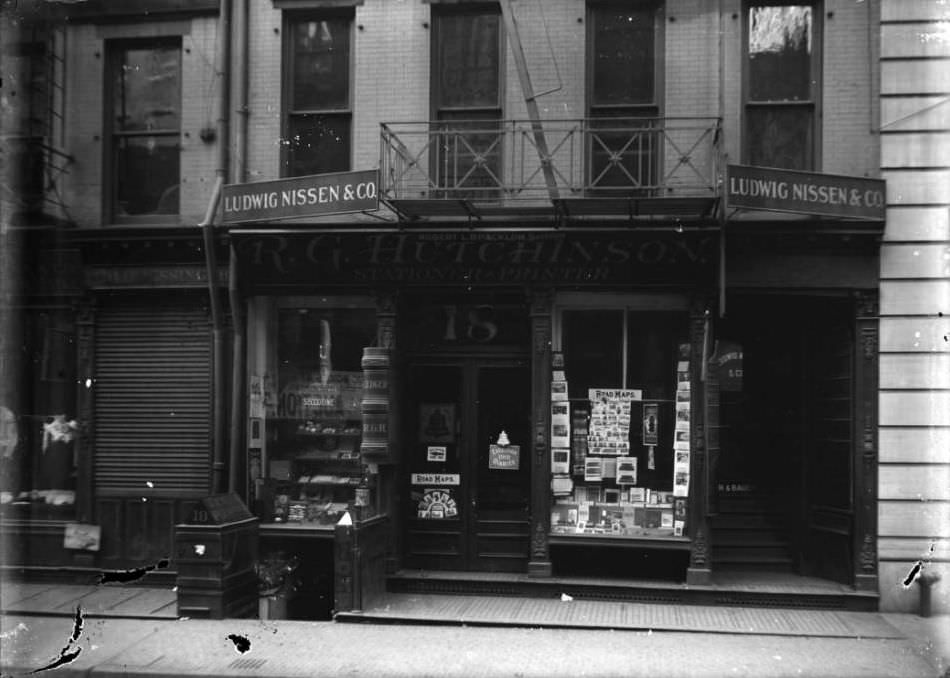

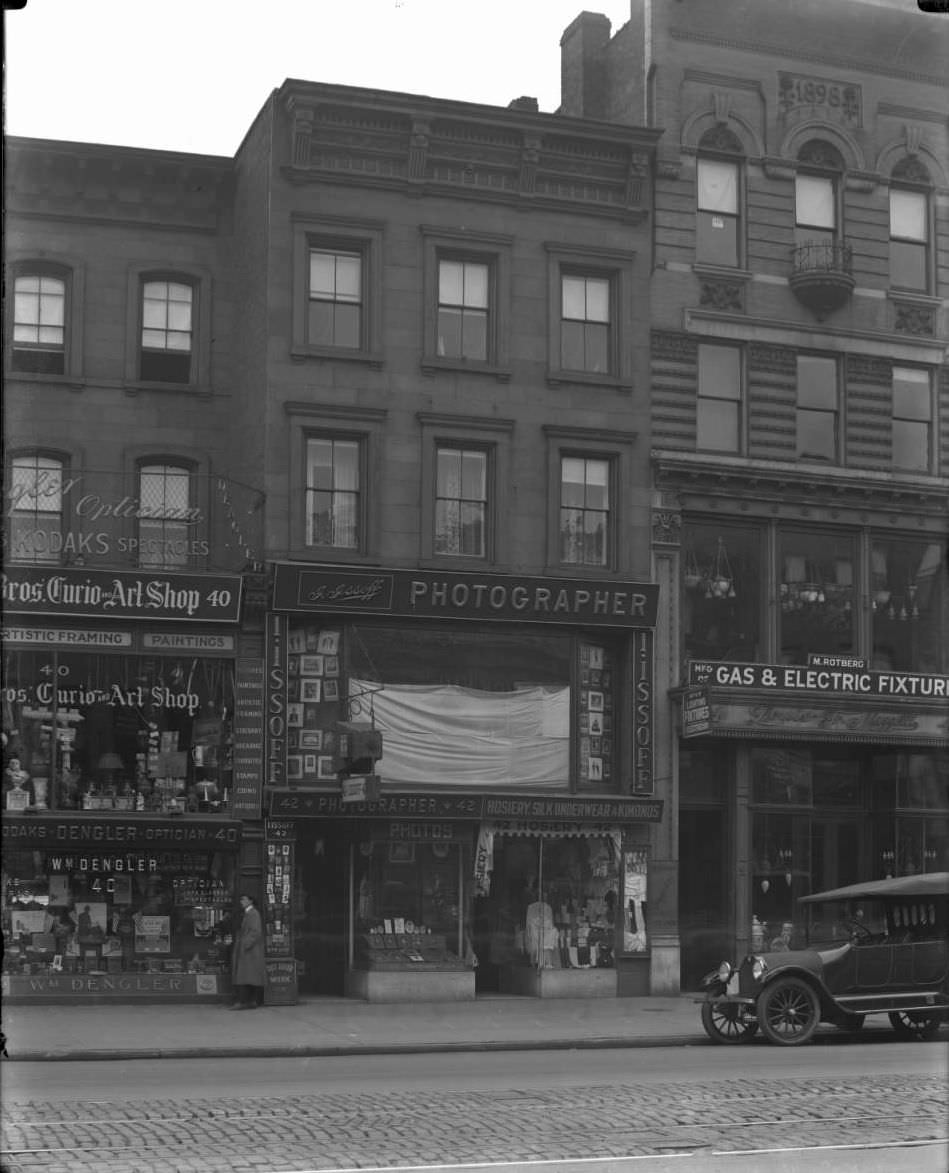

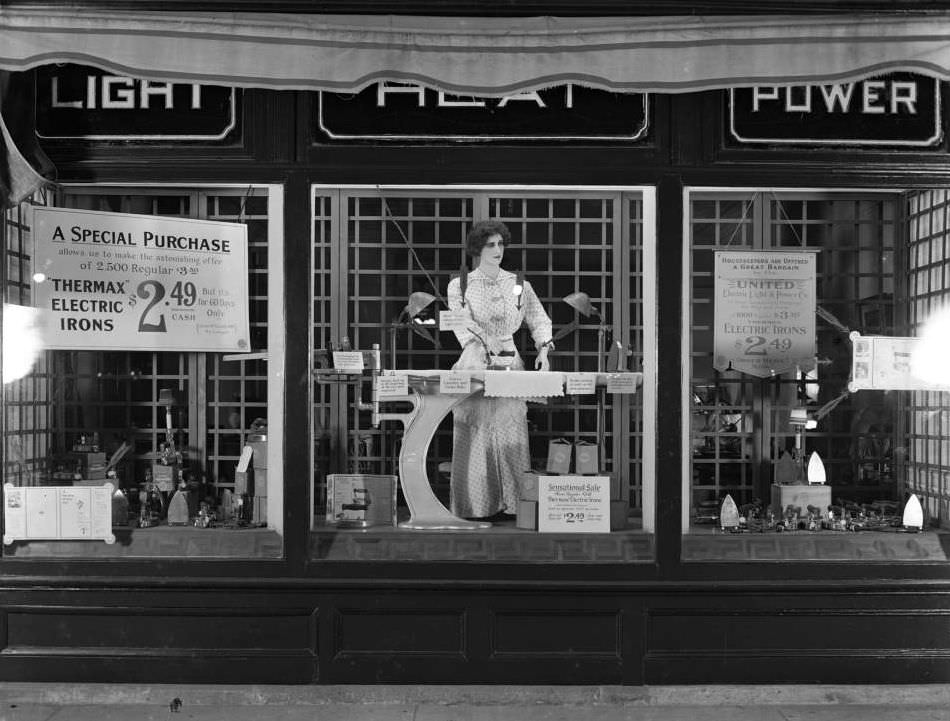

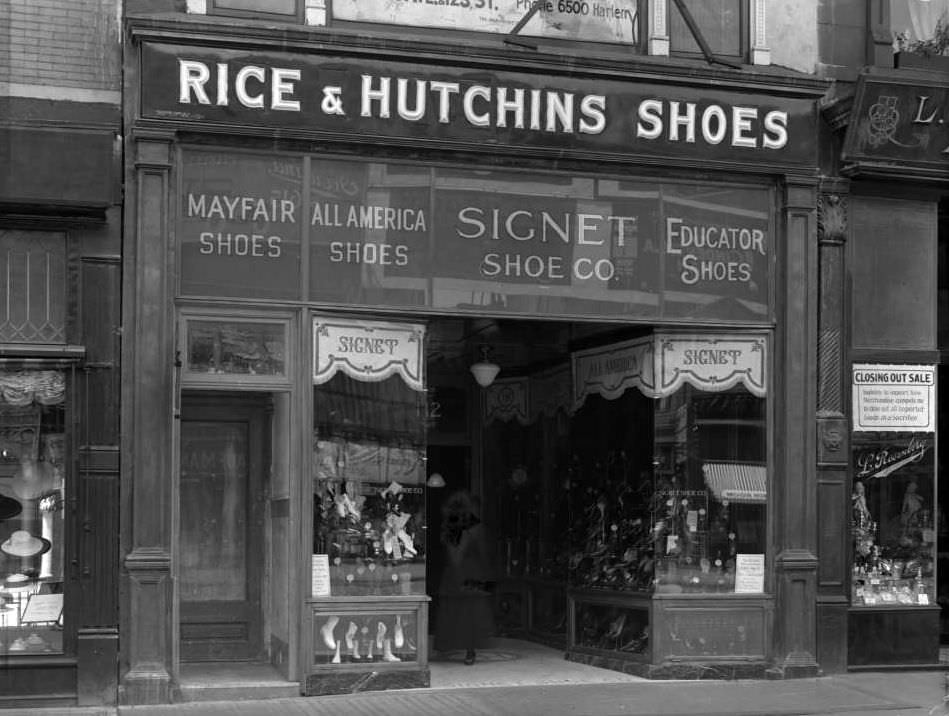

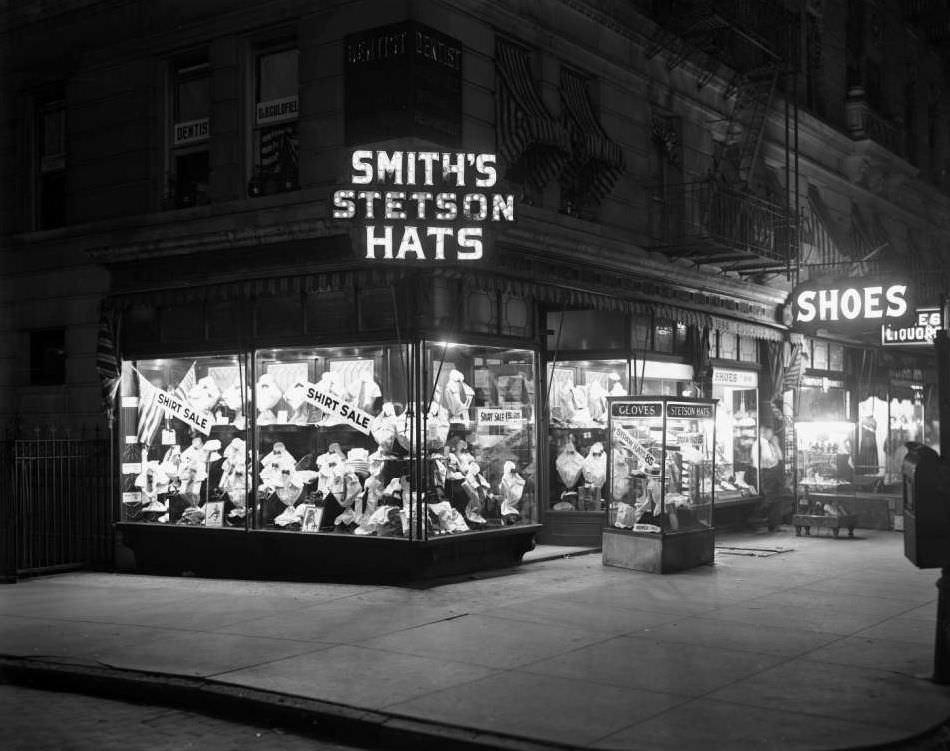

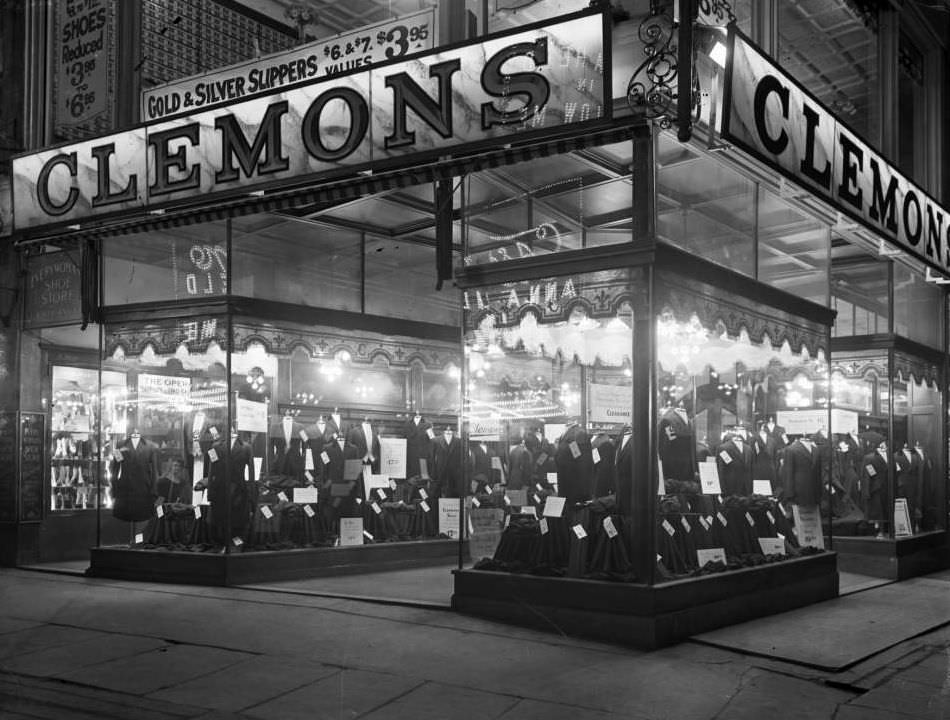

A typical storefront of the era had a distinct structure. The main feature was the large, single-pane plate glass window, a relatively modern innovation that allowed for an unobstructed view of the goods inside. The entrance was often recessed, set back from the sidewalk to create a small, sheltered entryway for customers. Above the main window and the door were smaller windows called transoms, which could be tilted open to allow for ventilation. Most shops had a large canvas awning that could be rolled out in the summer to shade the interior and protect the goods in the window display from the sun.

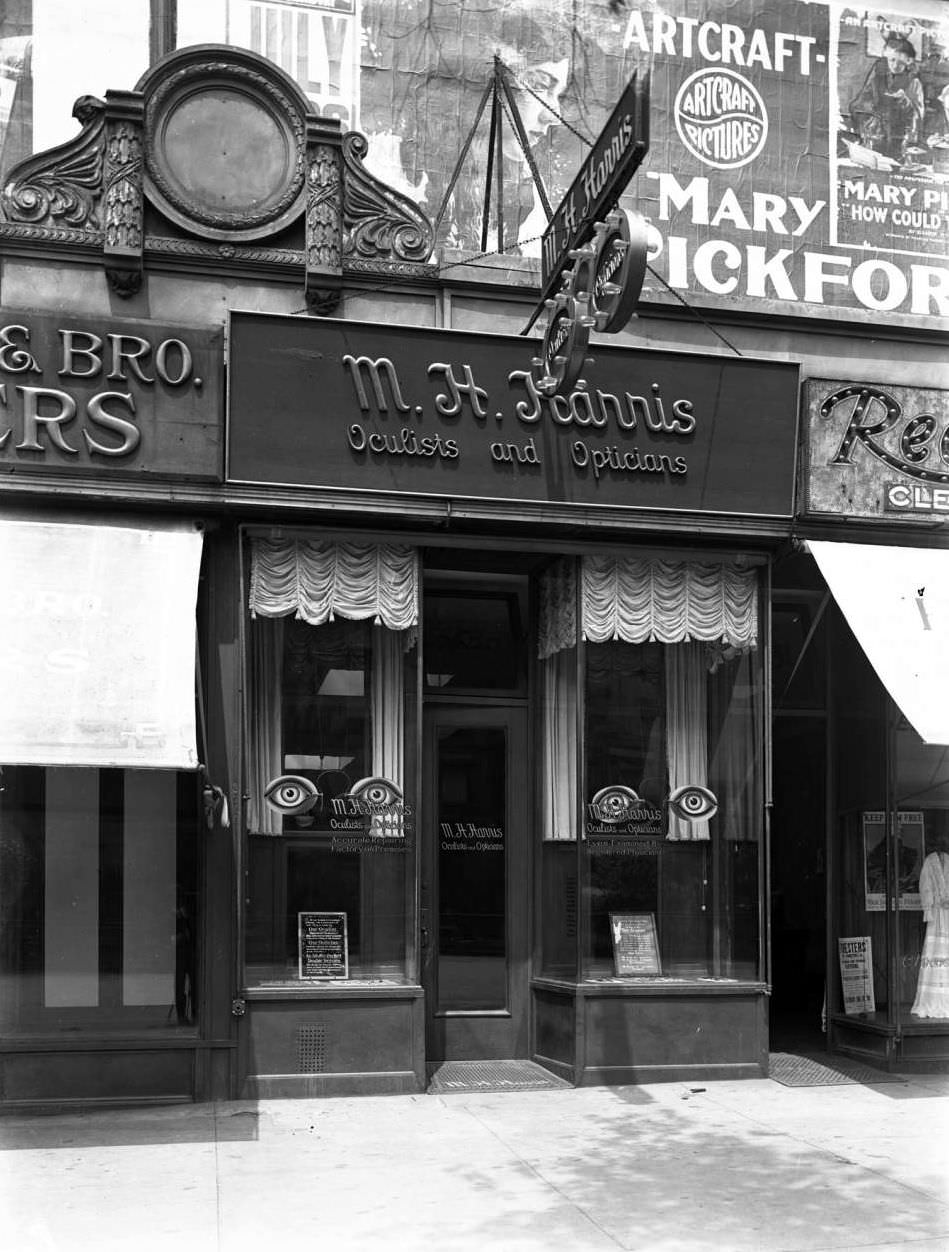

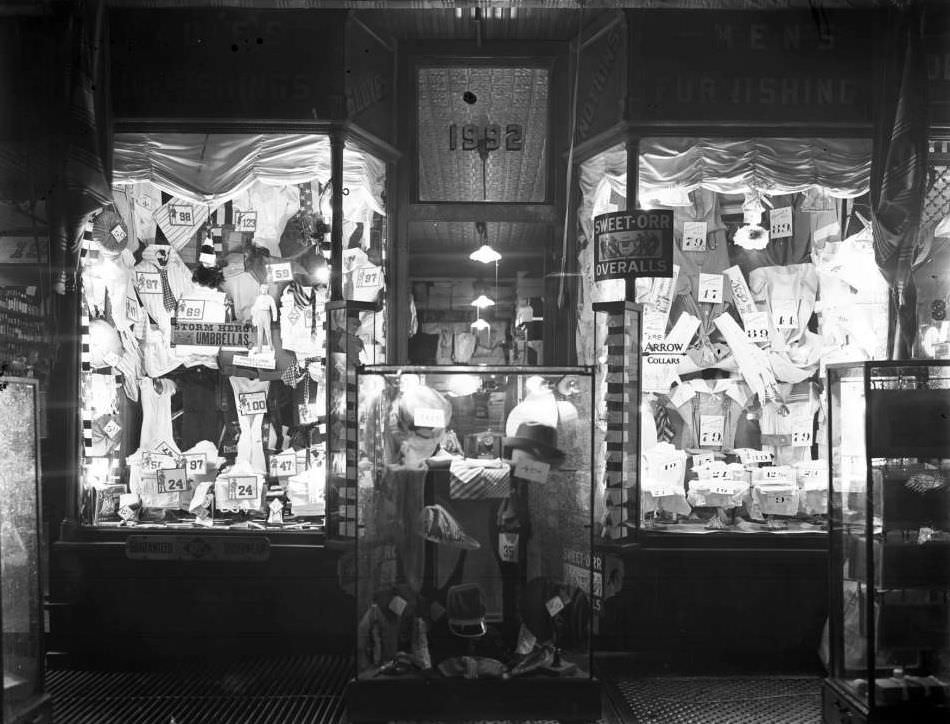

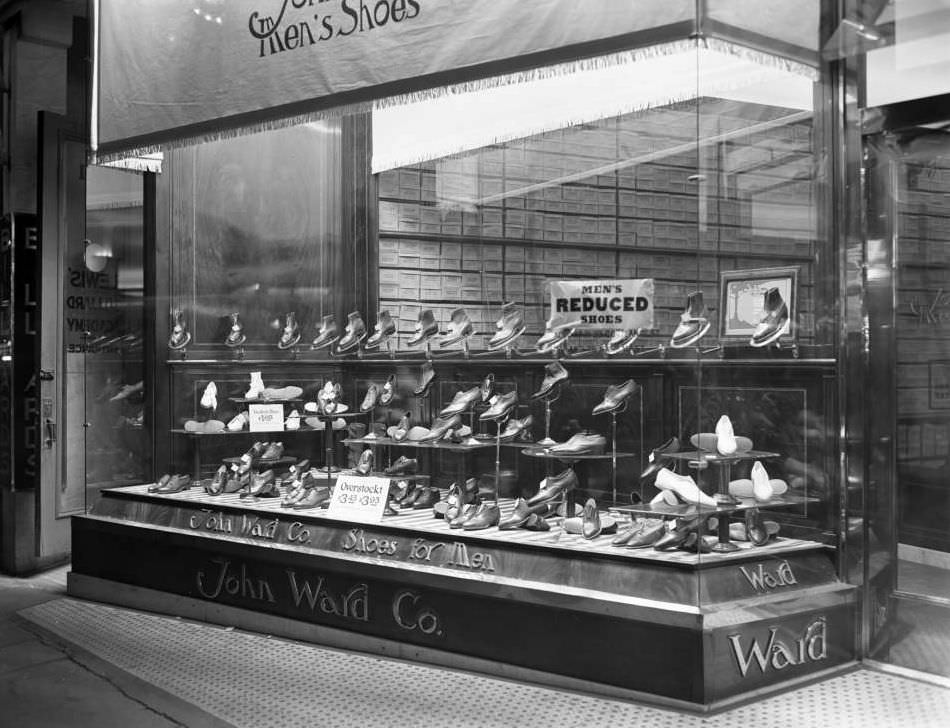

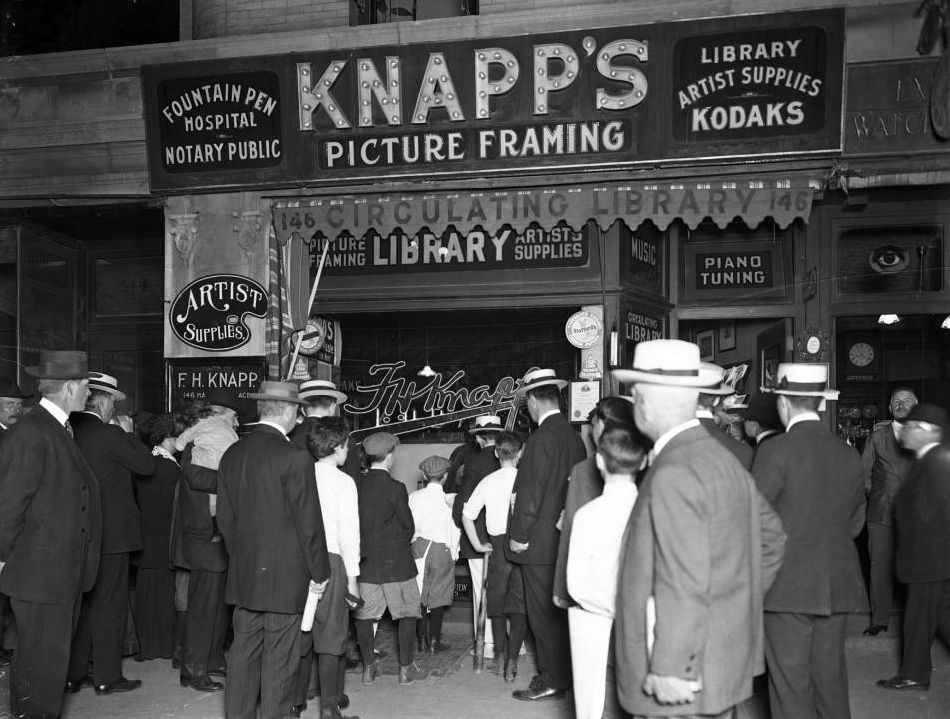

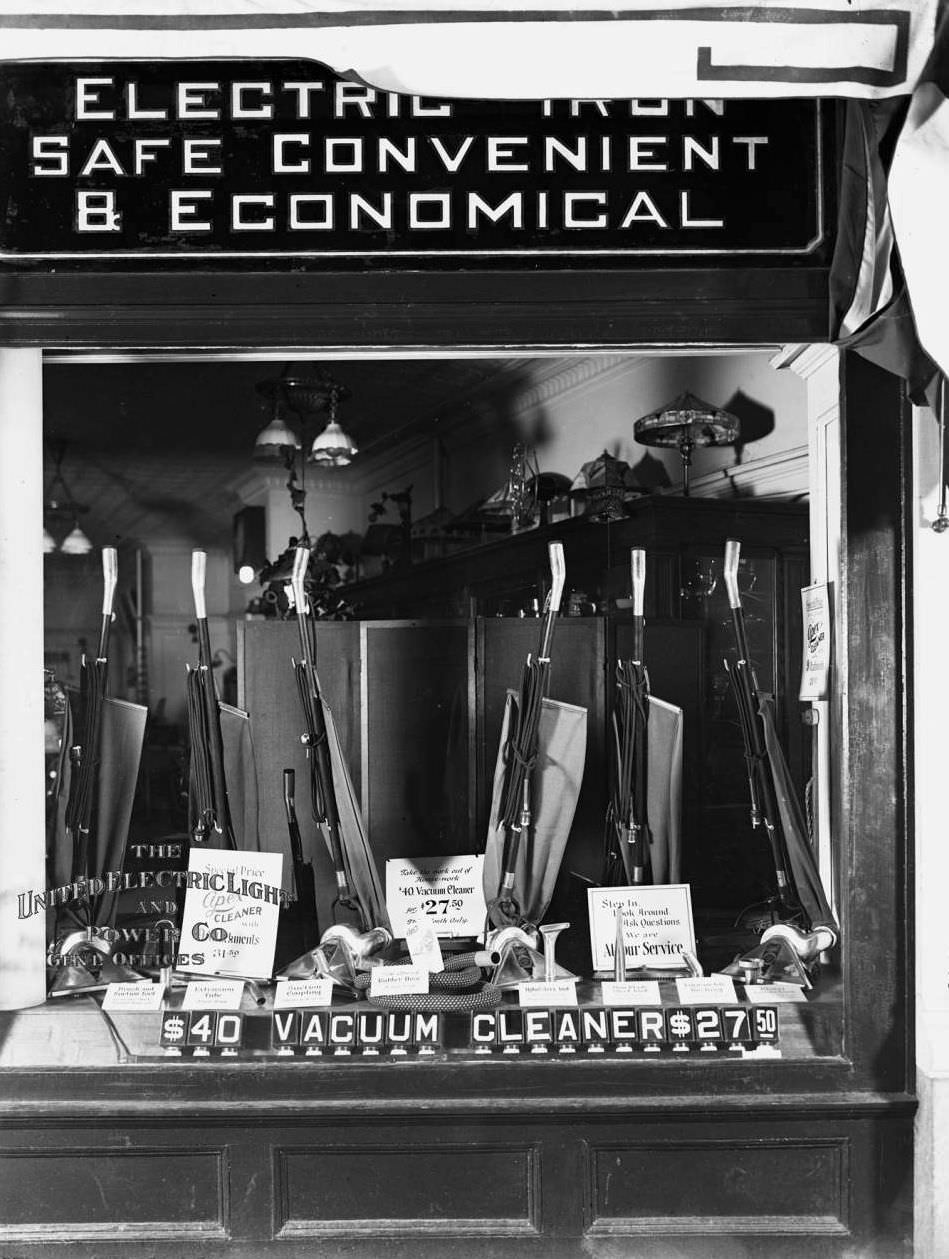

Signage was an art form. The most common and elegant type was hand-painted gold leaf lettering applied directly to the inside of the glass windows, announcing the name of the proprietor and the nature of the business. Carved and painted wooden signs were also hung above the doorway. Prices and daily specials were often written in chalk on small slate boards or hand-painted on paper signs and taped inside the window.

Read more

The appearance of these storefronts varied dramatically across the city. On Fifth Avenue, luxury retailers like Tiffany & Co. and the department store B. Altman and Company had opulent storefronts with bronze-framed windows, polished granite or marble bases, and elegant, uncluttered displays. Their window dressing was becoming a theatrical art, with a few select items carefully arranged to project an image of exclusivity and high fashion.

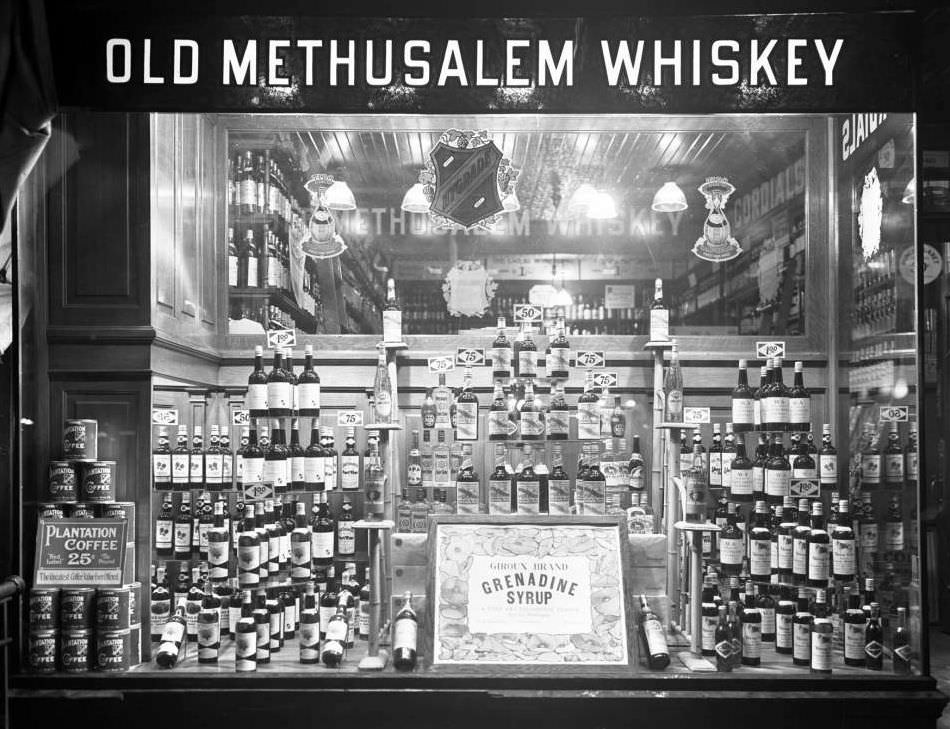

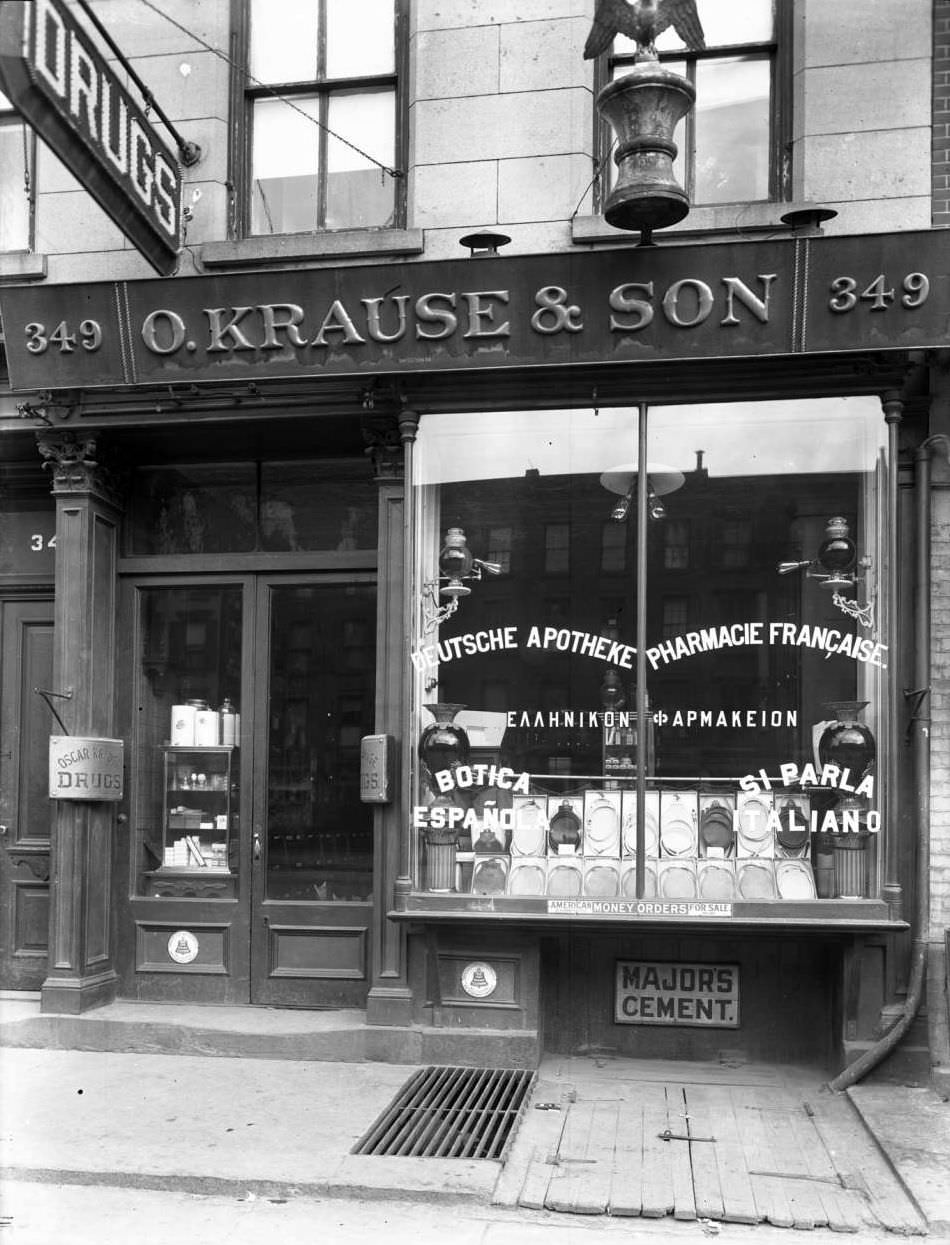

In contrast, the storefronts of working-class neighborhoods were dense with goods and information. On a street in the Lower East Side, a grocery store would have barrels of pickles or sacks of potatoes on the sidewalk right outside the door. The windows would be packed with canned goods, hanging sausages, and advertisements. A bakery’s window would be filled with rows of bread, rolls, and cakes, with the prices written on small cards. A butcher shop would have its name in bold letters and might have freshly dressed poultry hanging in the open air.

Specific trades had their own unique storefront features. The windows of a pharmacy were distinguished by large, ornate glass vessels known as show globes, which were filled with colored water. Saloons, which were found on nearly every corner, featured swinging “batwing” doors that allowed for easy entry while providing a degree of privacy. Their windows were often made of frosted or ornately etched glass to obscure the view of the patrons inside.

Are you able to provide a source for any of these images? Asking so I can find some more!