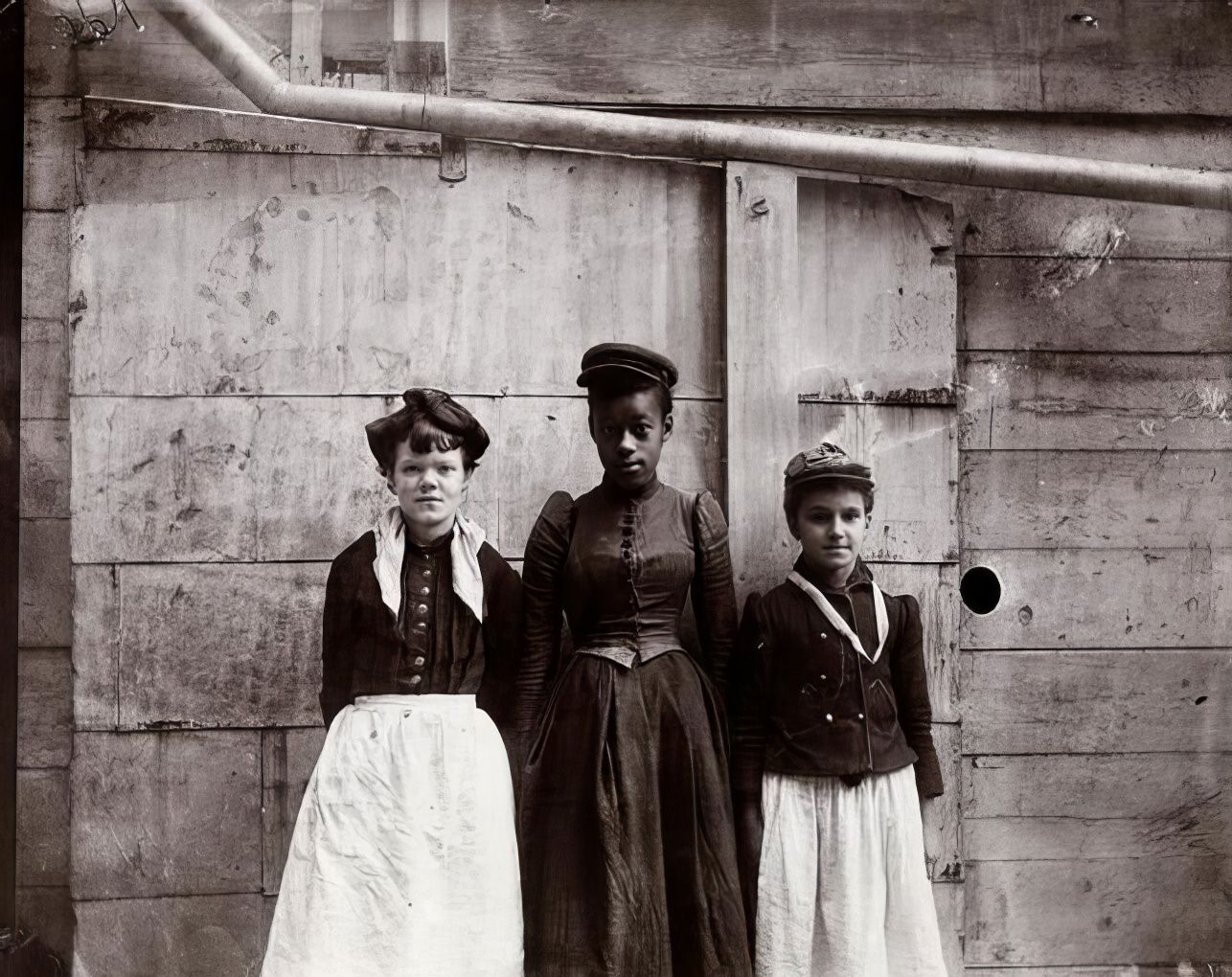

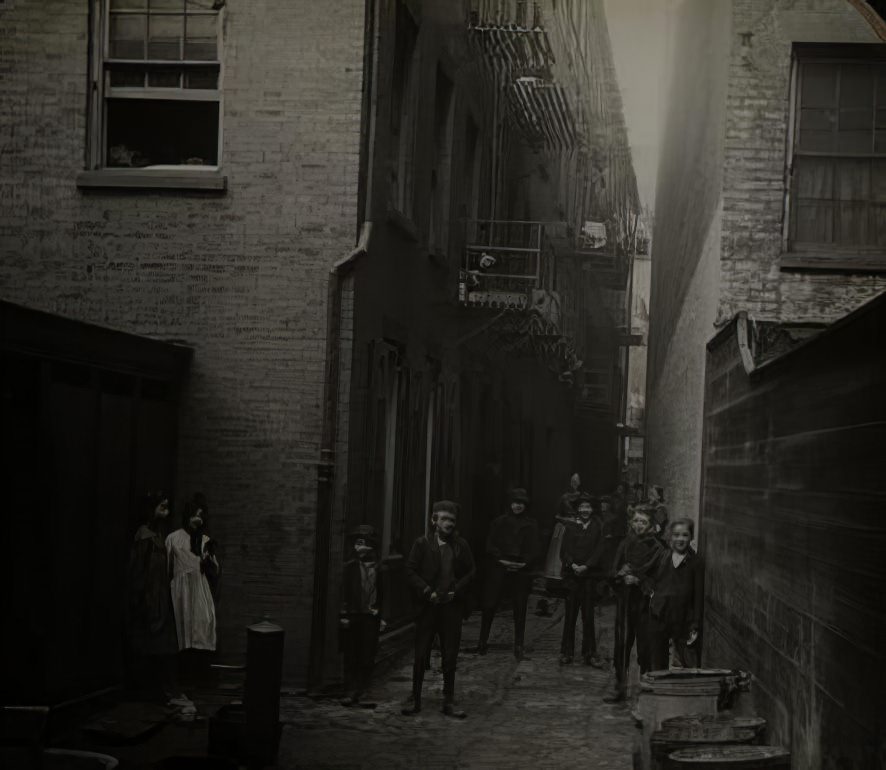

In the late 19th century, New York City was changing fast. Immigrants were arriving by the thousands each week. They came from Ireland, Italy, Germany, Russia, and many other countries. By 1880, the city’s population had doubled. This caused serious overcrowding, especially in lower Manhattan. The city had no plan for this sudden growth. Landlords rushed to profit from it.

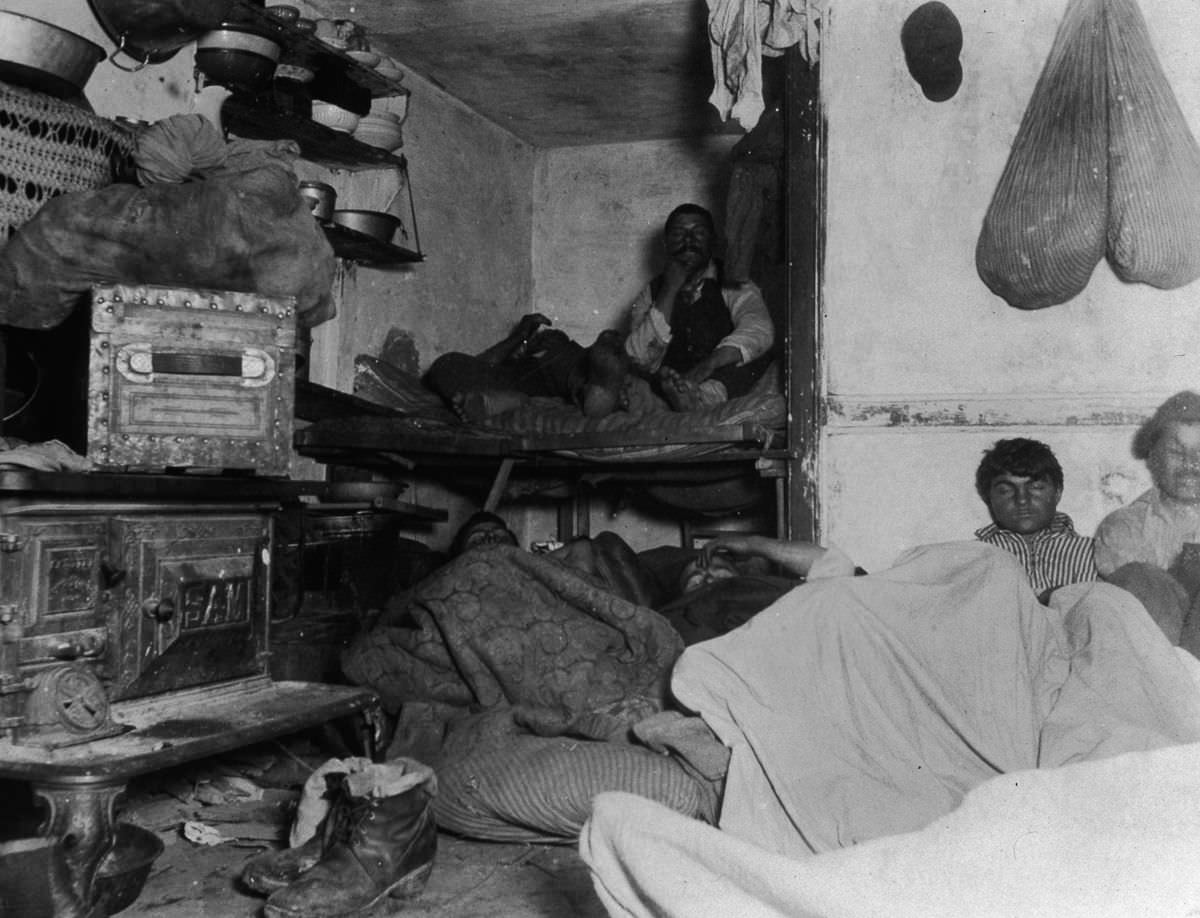

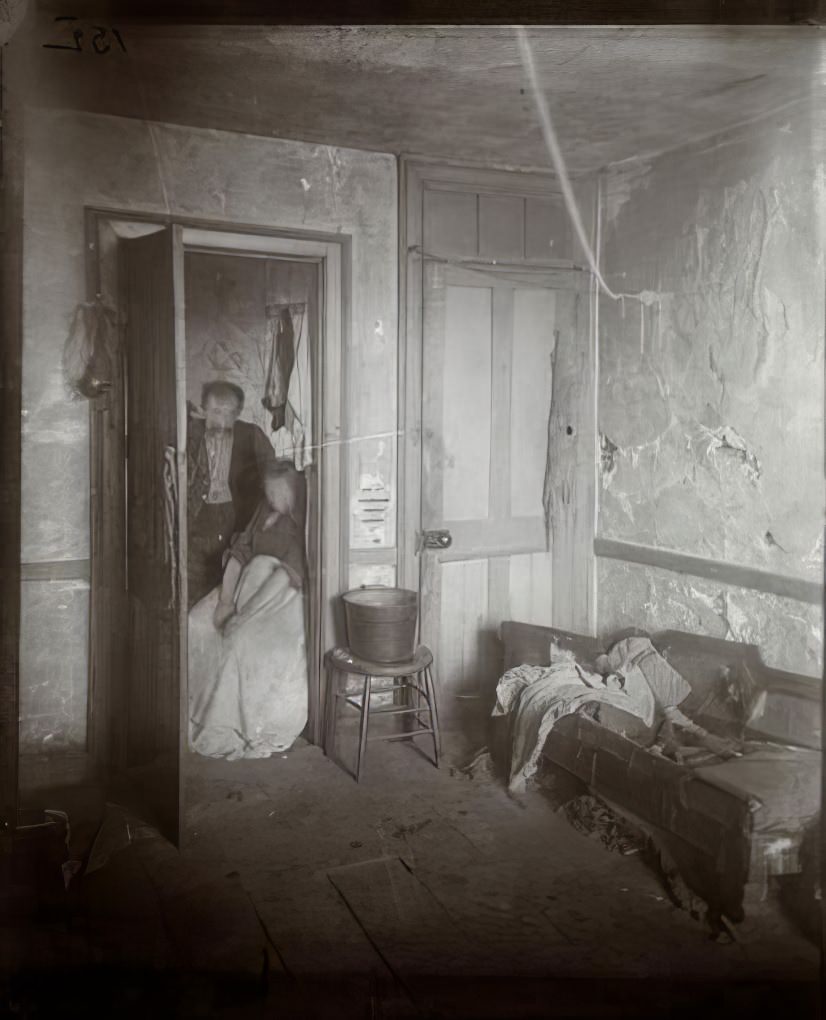

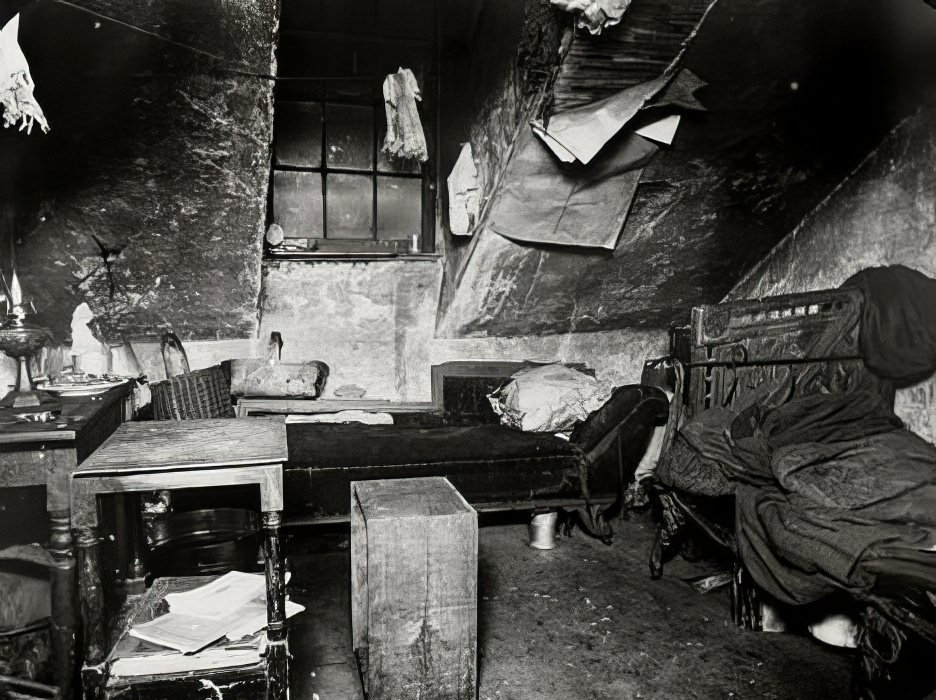

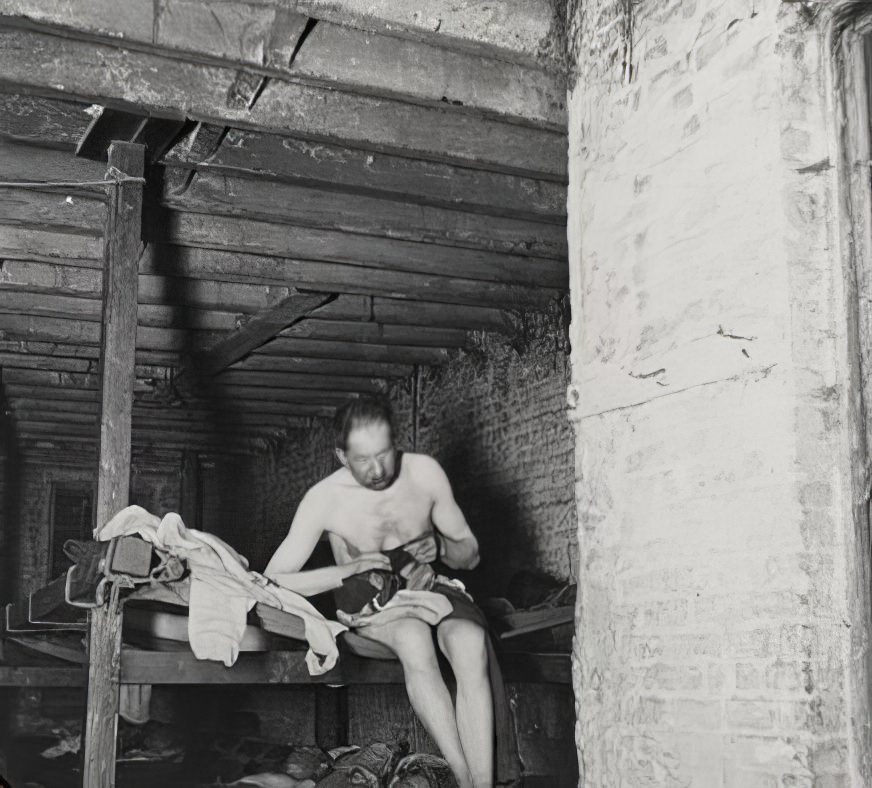

They bought buildings and split them into small, dark spaces. Homes once meant for a single family were packed with several. A room that once had a bed for one now held three or four. People slept in shifts or on the floor. Privacy did not exist. In some buildings, over a hundred people lived under one roof.

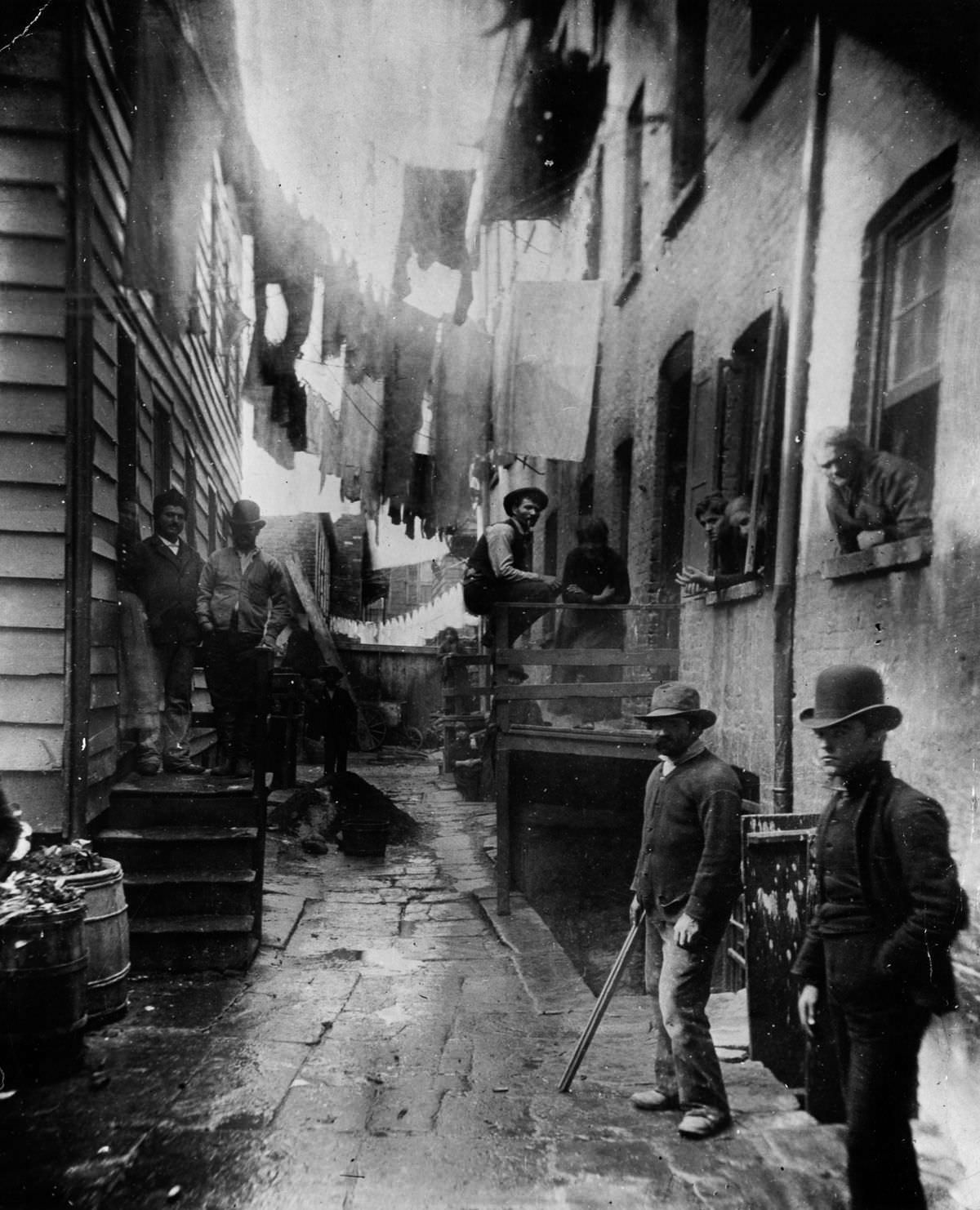

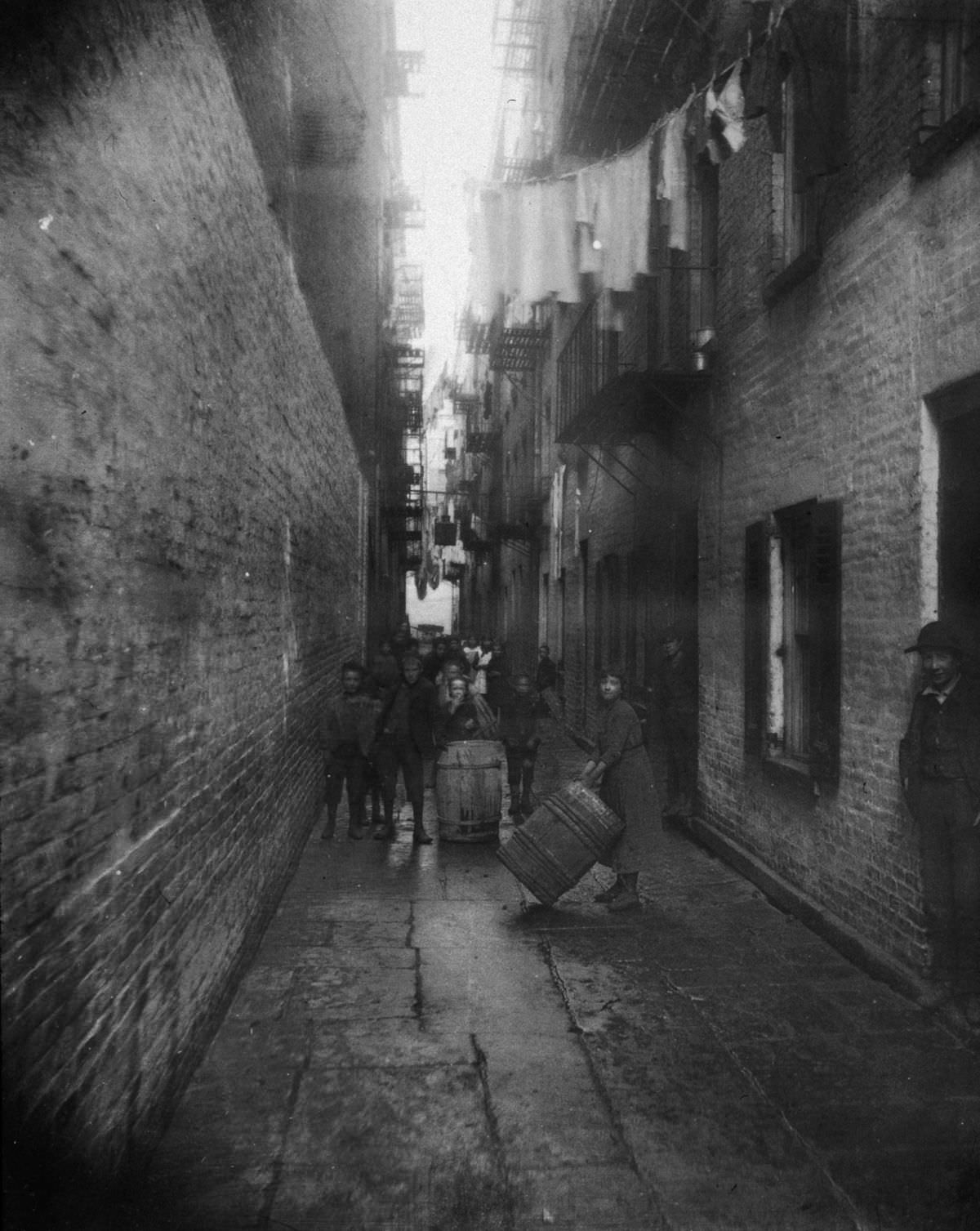

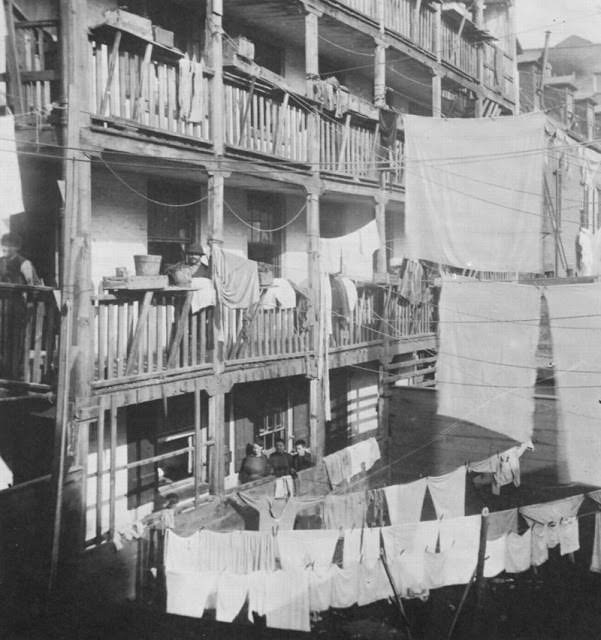

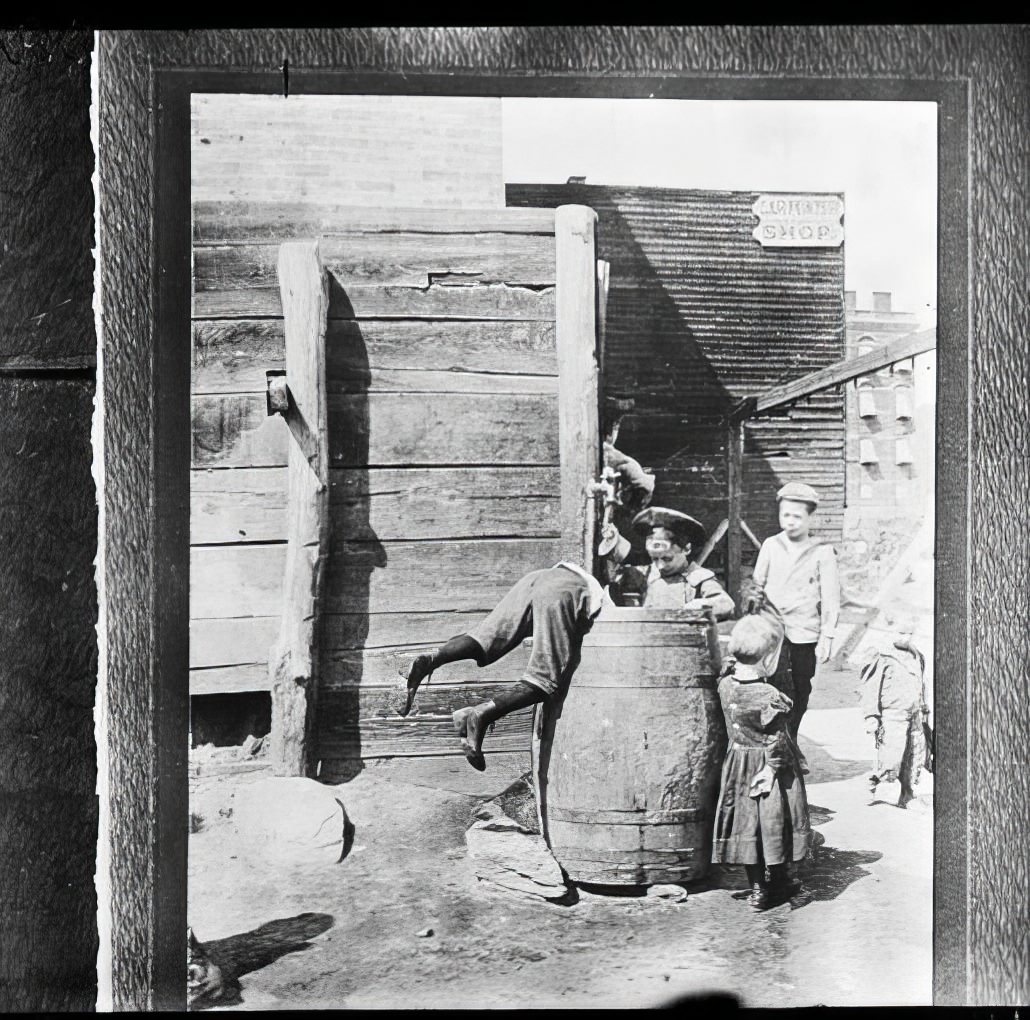

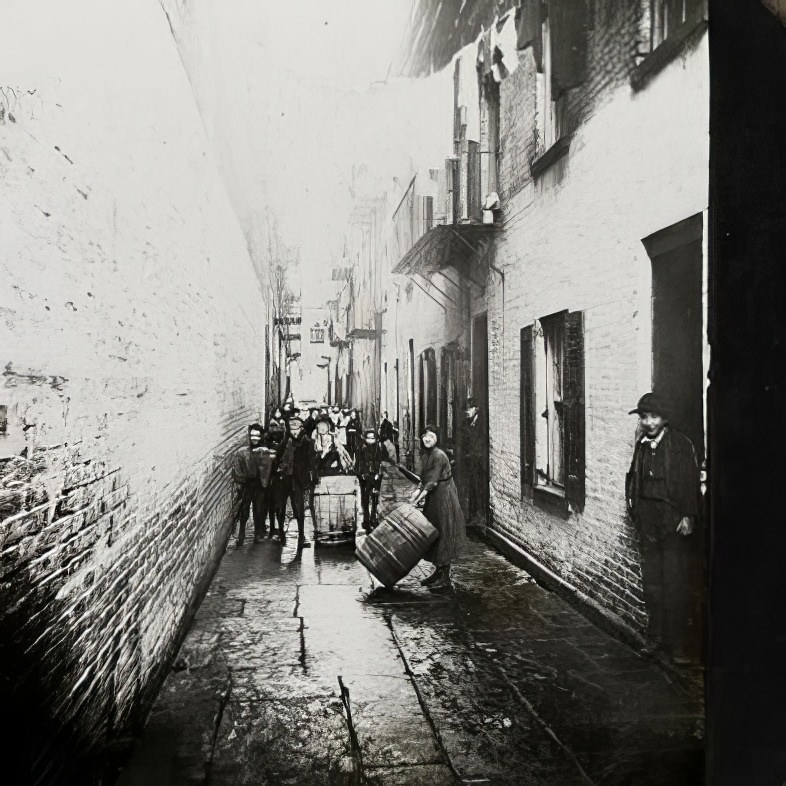

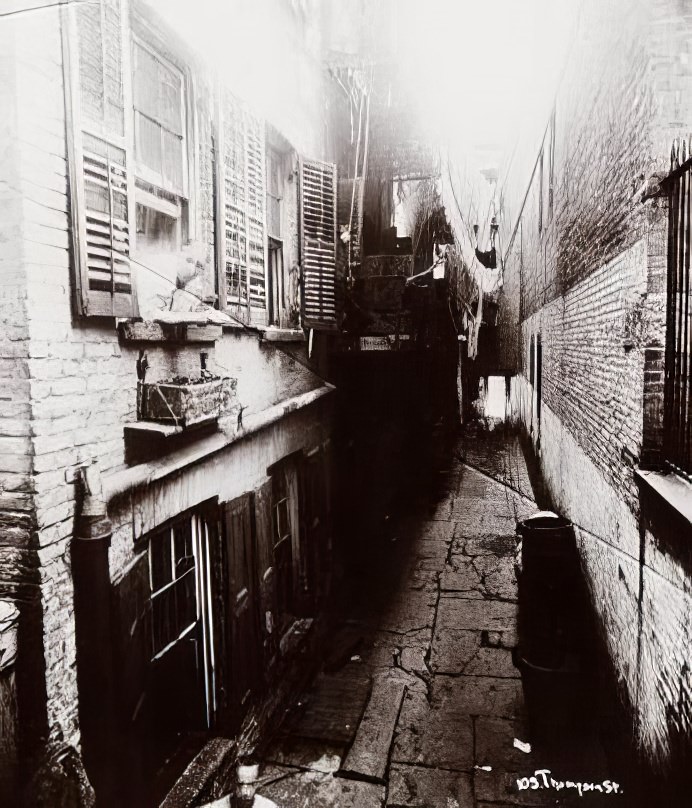

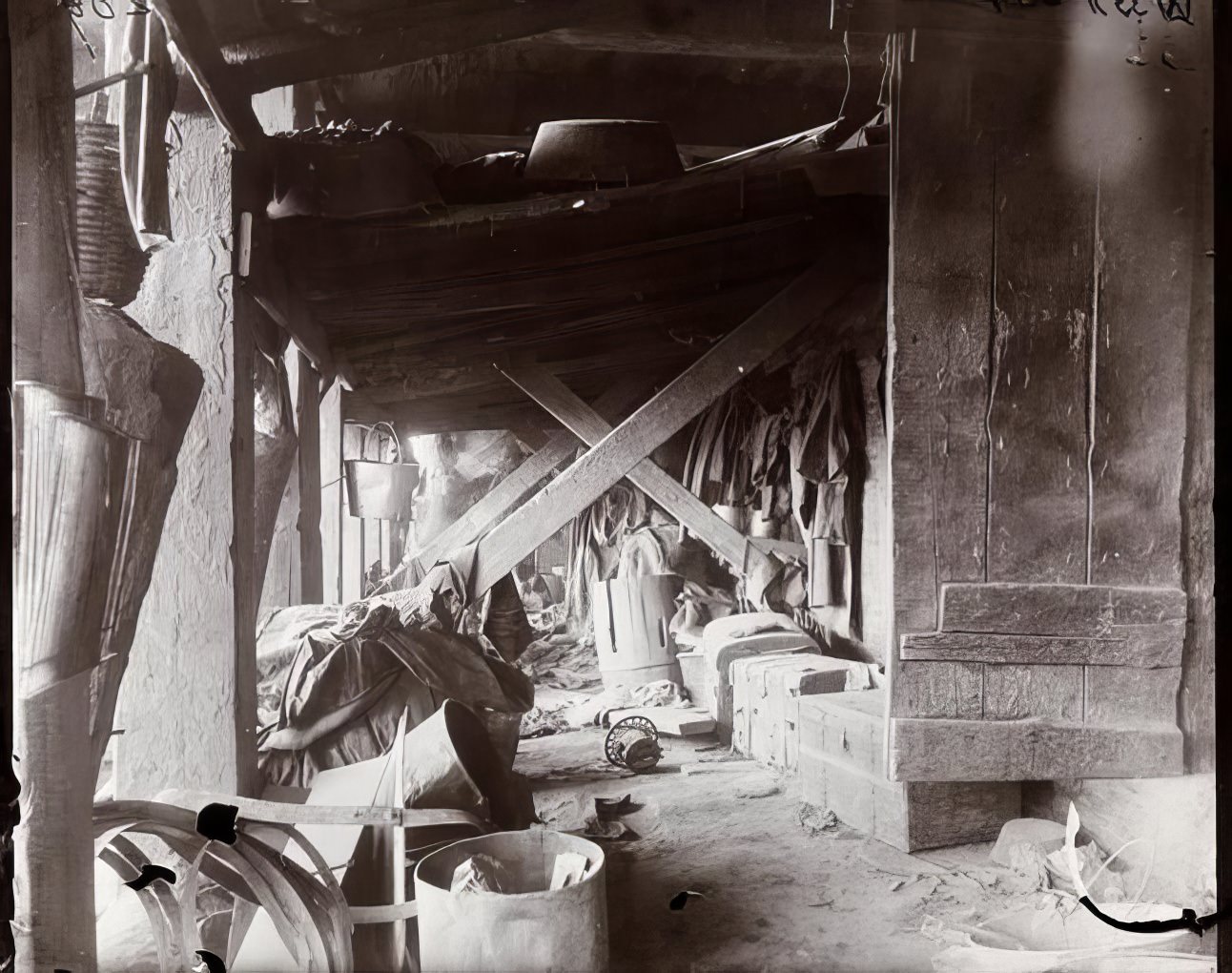

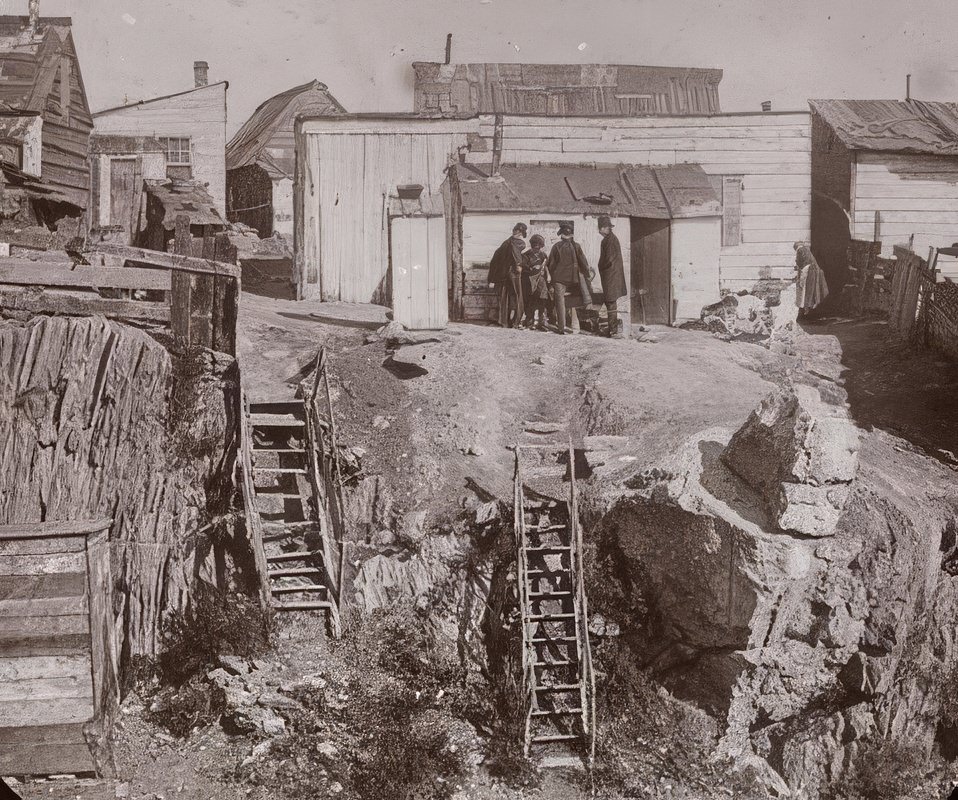

Tenements were the most common housing. These were narrow buildings, often five or six stories tall. Most were built cheaply. Builders used poor materials and didn’t follow safety rules. The rooms had no windows or fresh air. Ventilation was almost zero. Fire was always a danger. Most tenements had no running water or toilets inside. Residents shared one or two outhouses in the backyard. The smell was overwhelming, especially in summer.

Read more

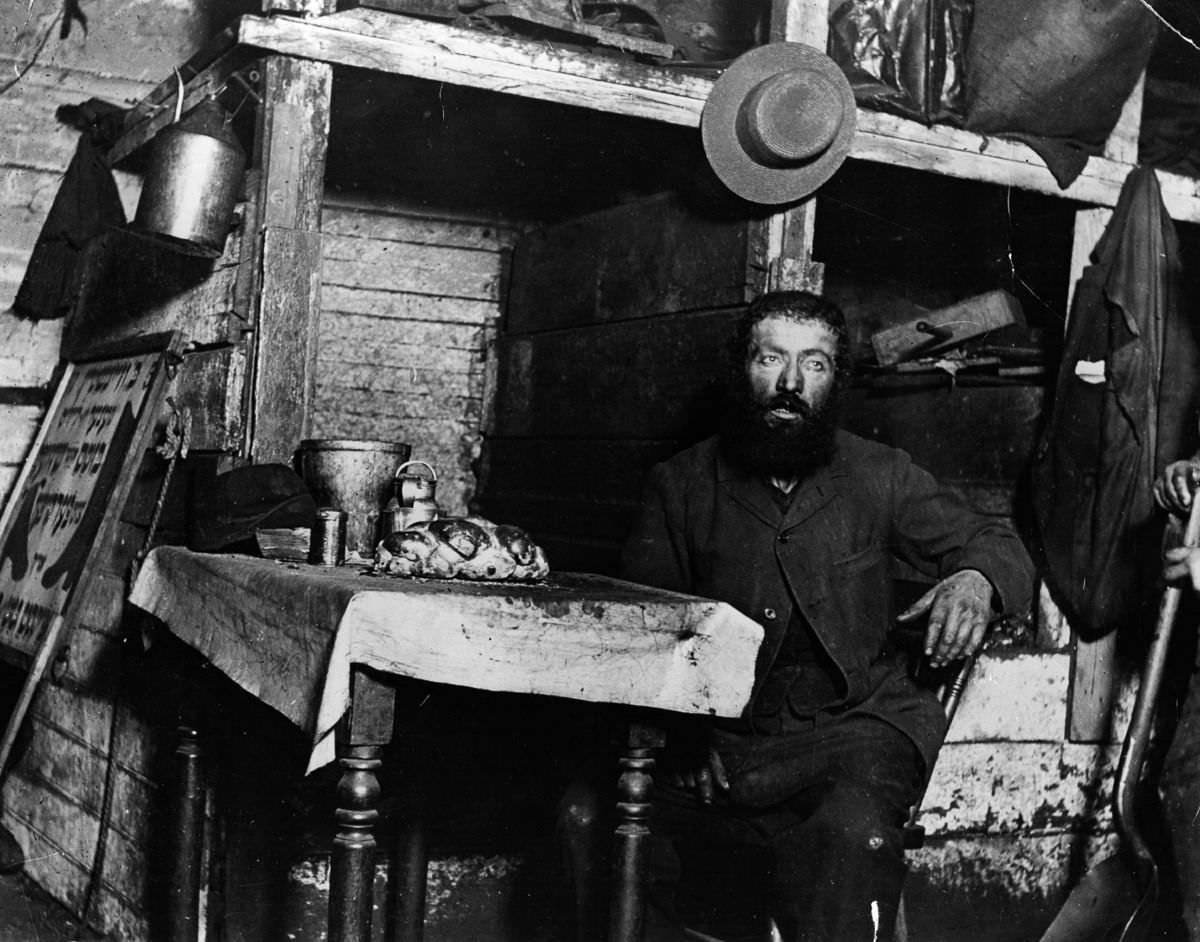

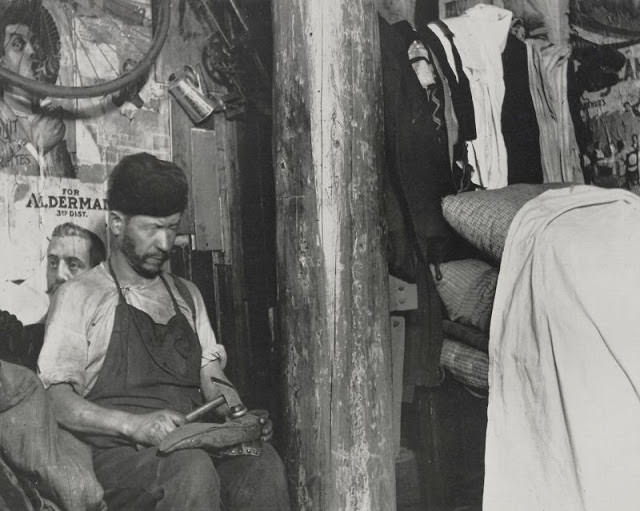

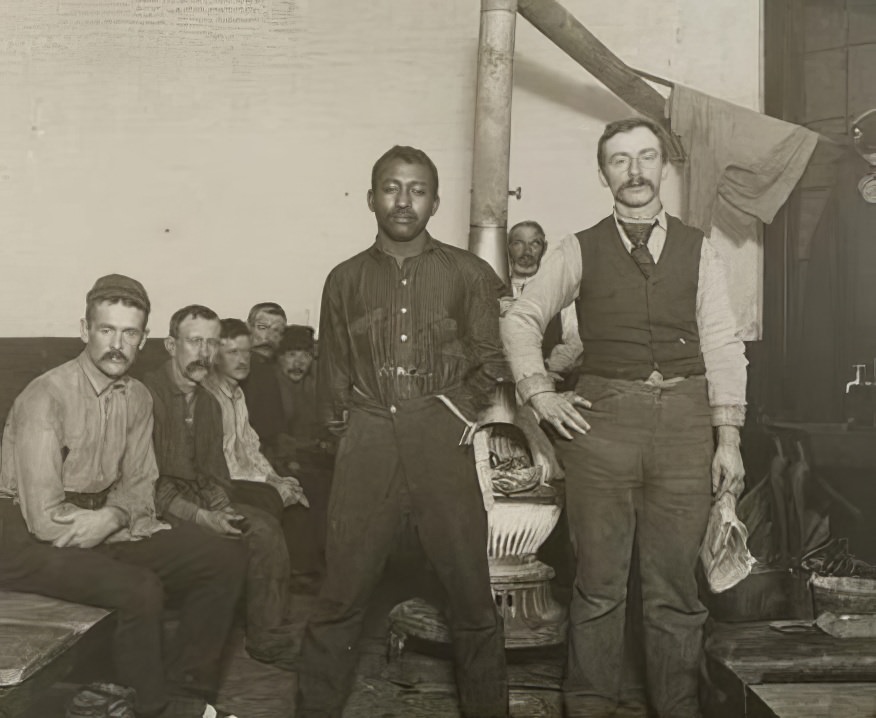

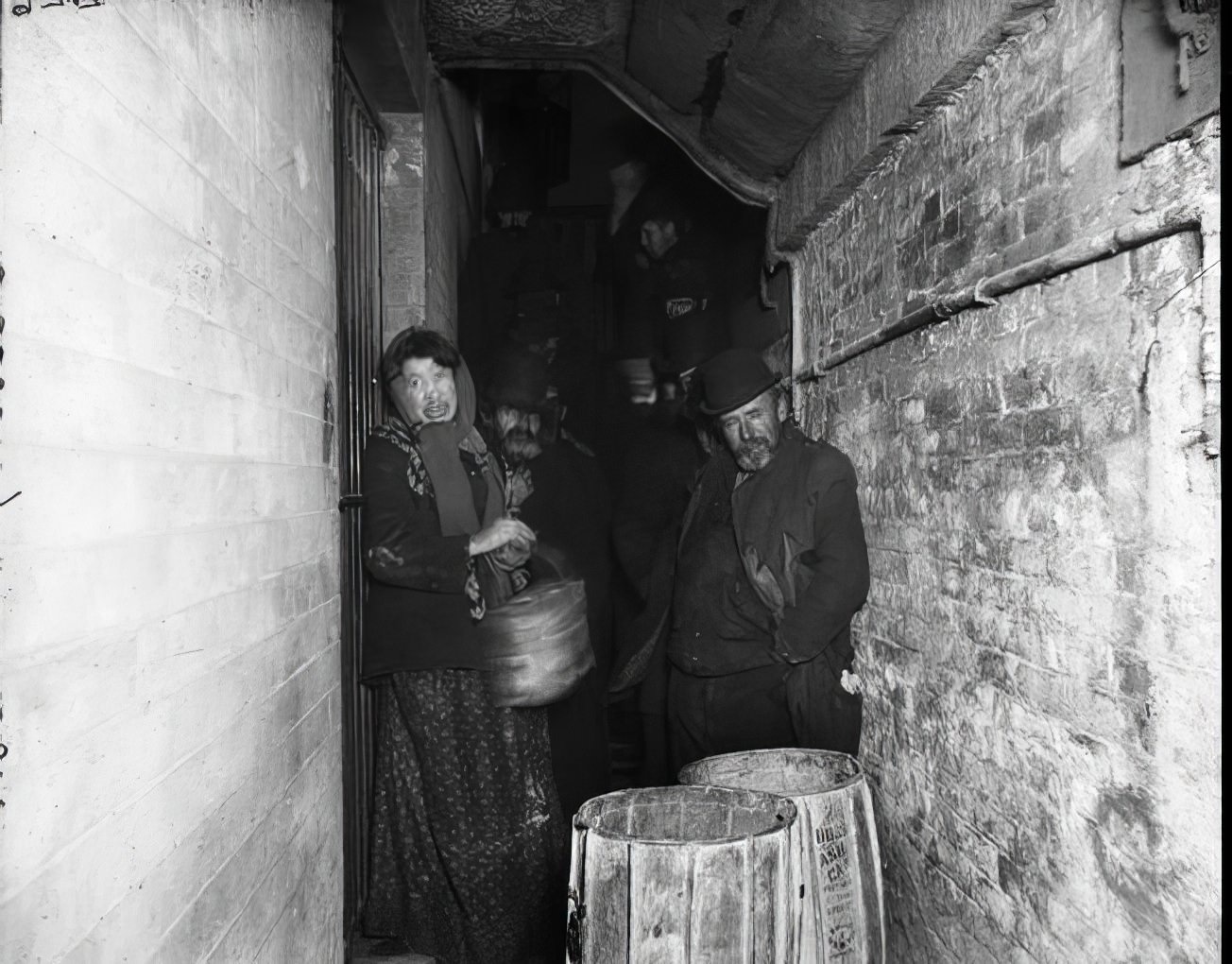

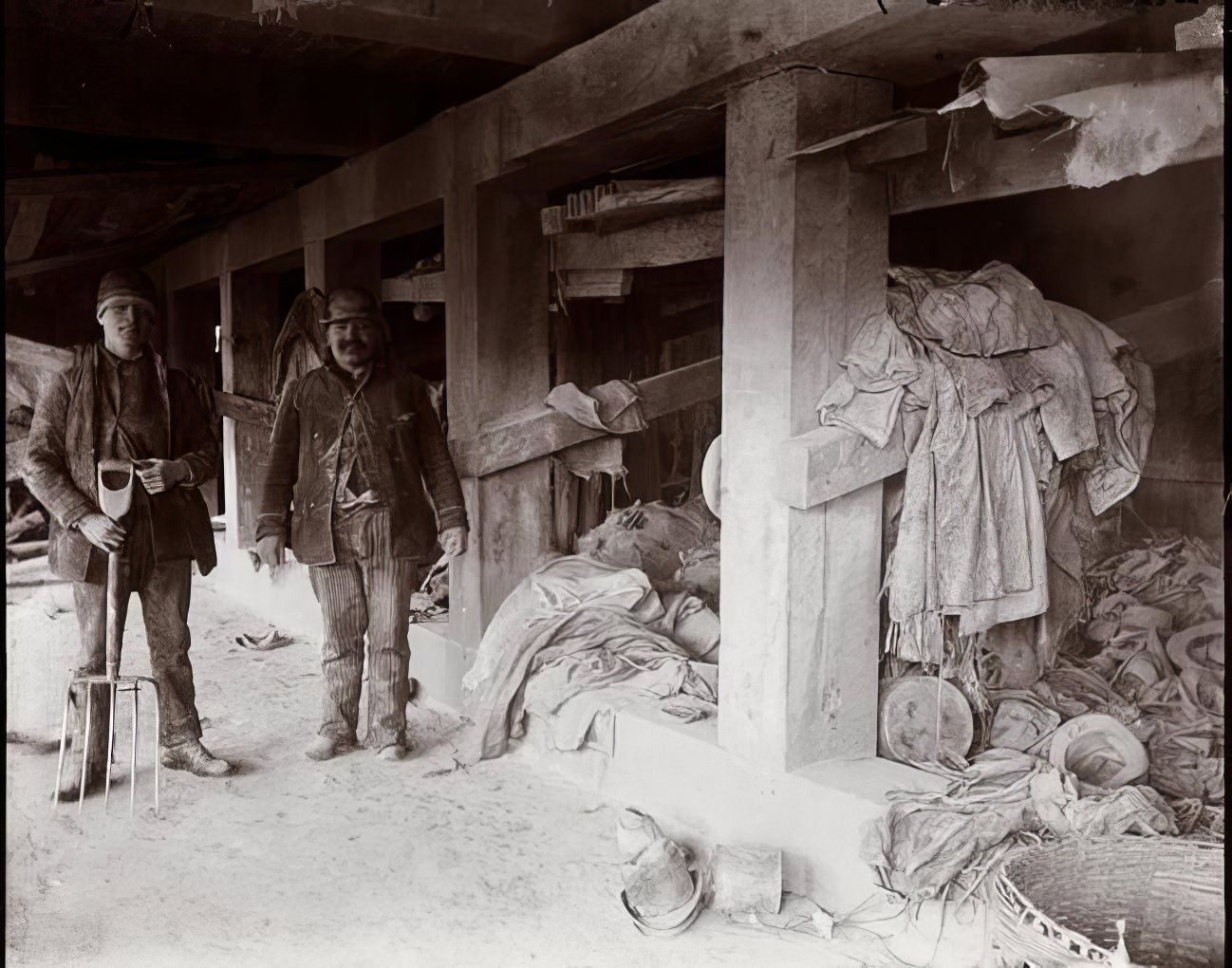

Jacob Riis, a Danish immigrant, saw these problems up close. He came to America in 1870 with only $40. He worked many jobs, including as a carpenter and iron worker. Later, he became a reporter for the New York Tribune. In 1888, he was assigned to cover police raids in the slums. What he saw shocked him.

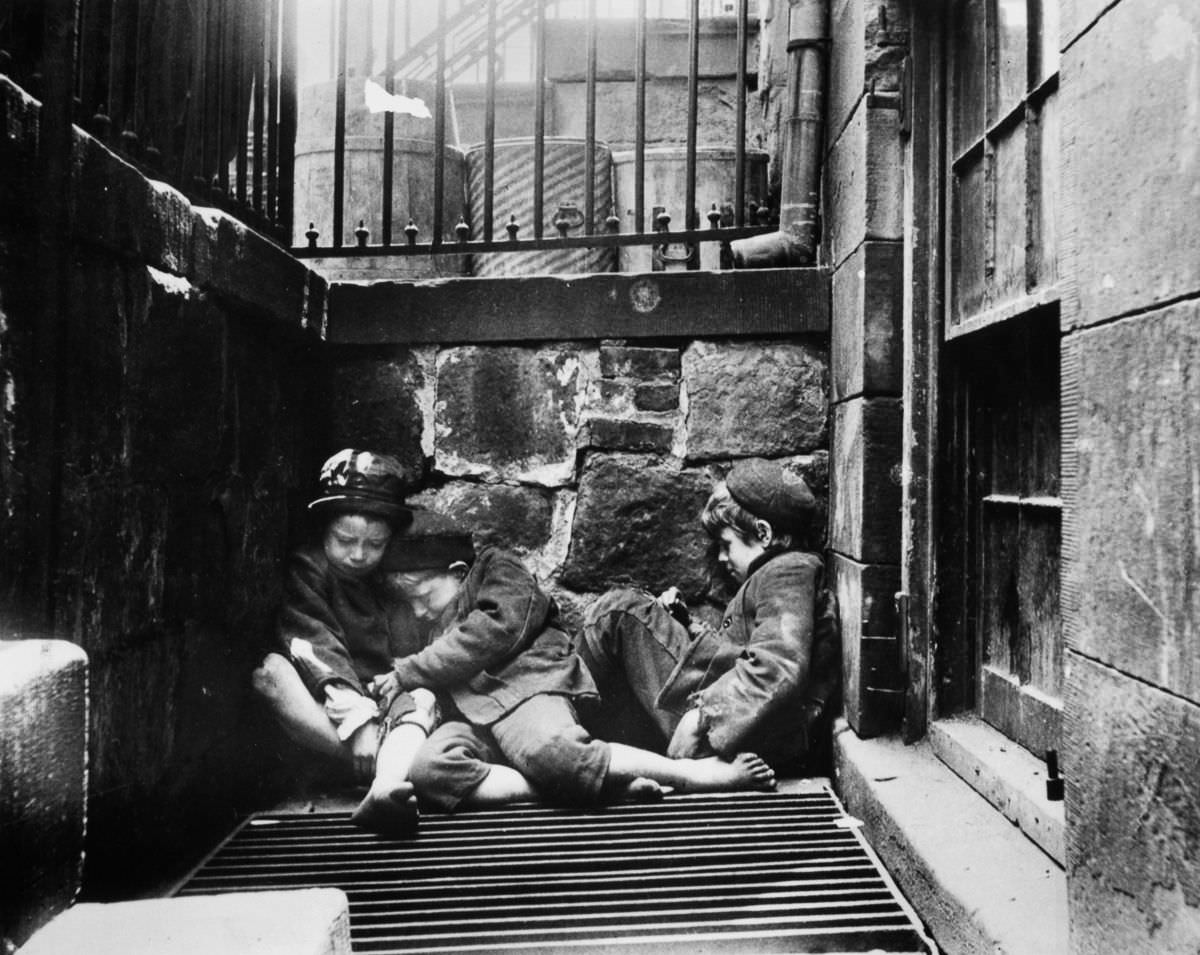

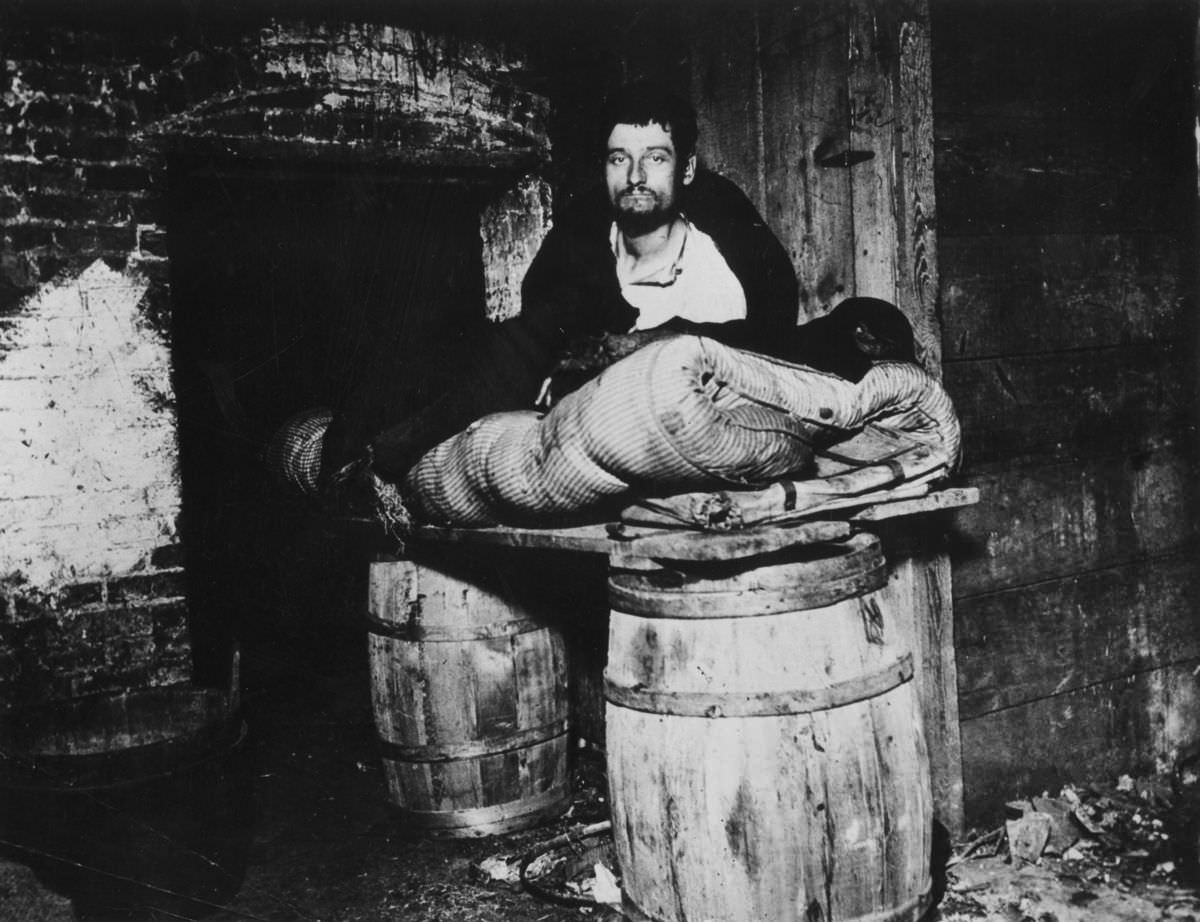

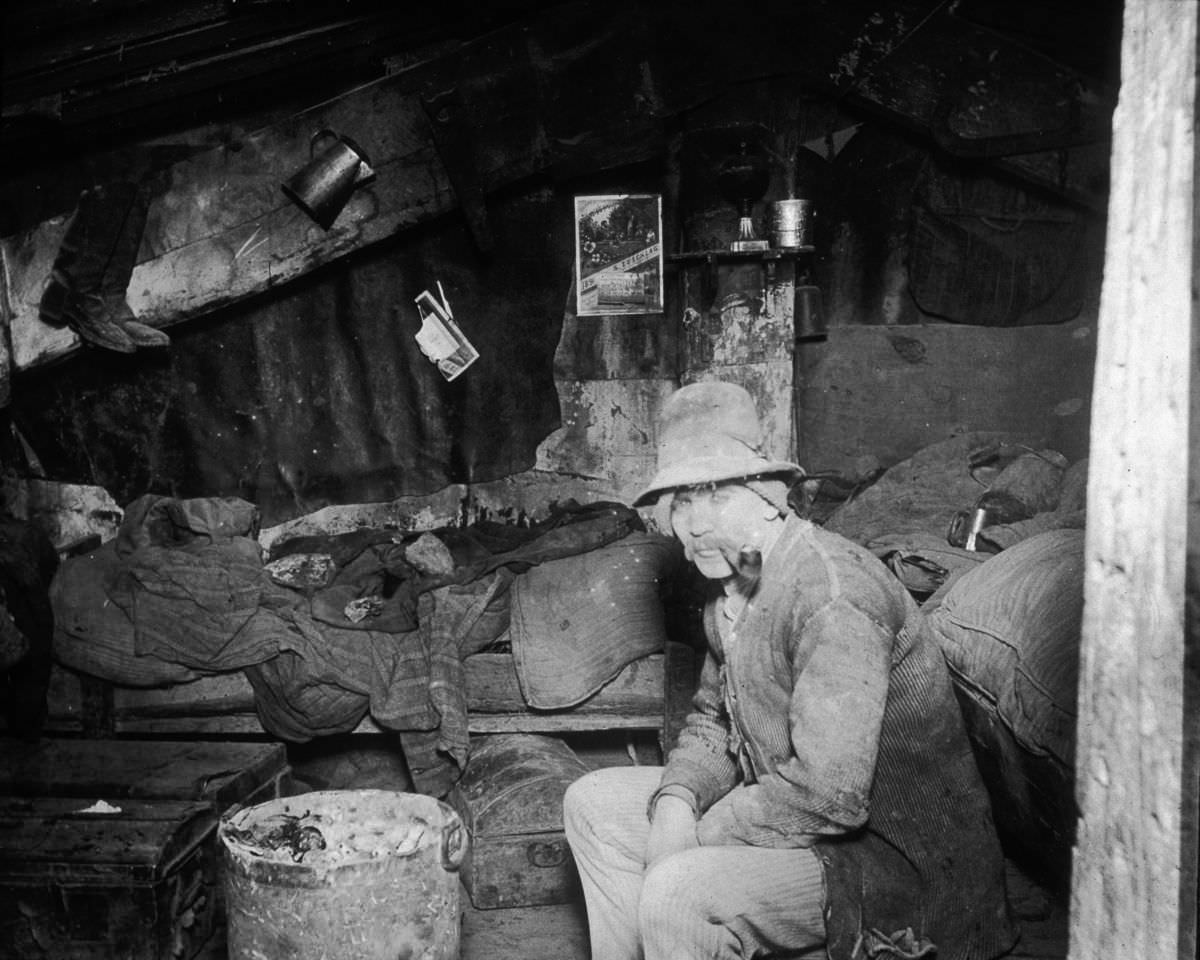

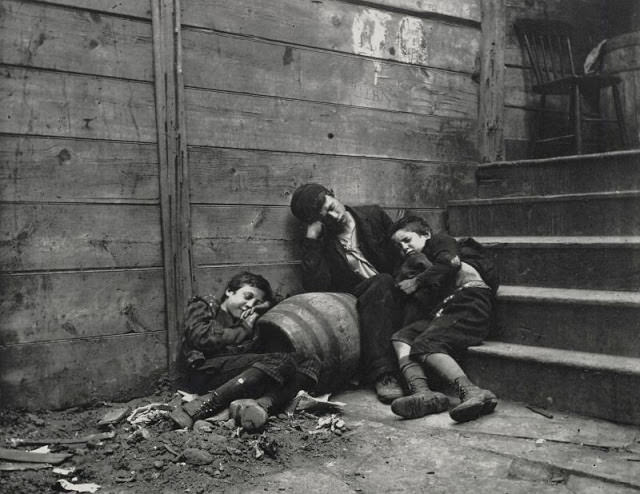

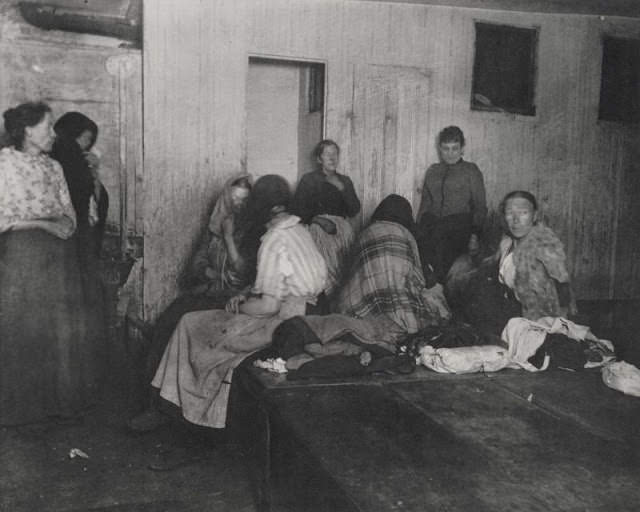

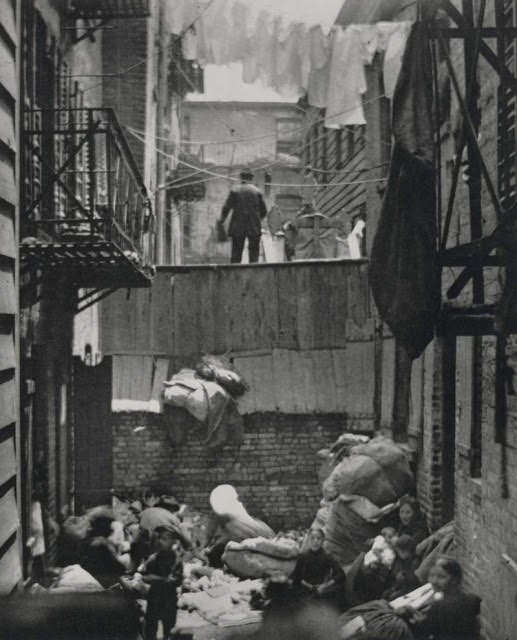

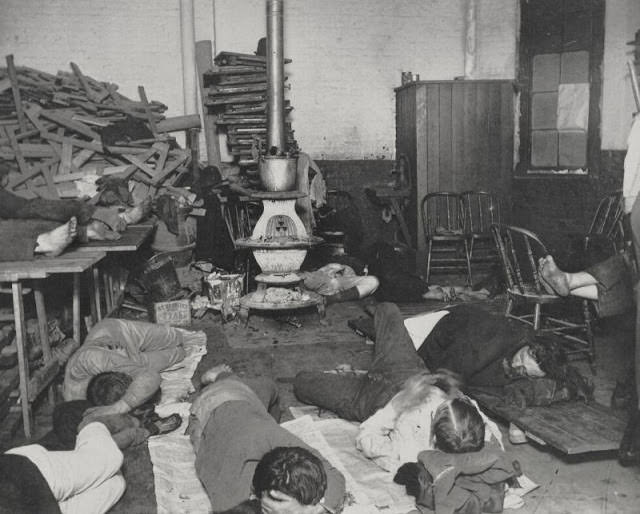

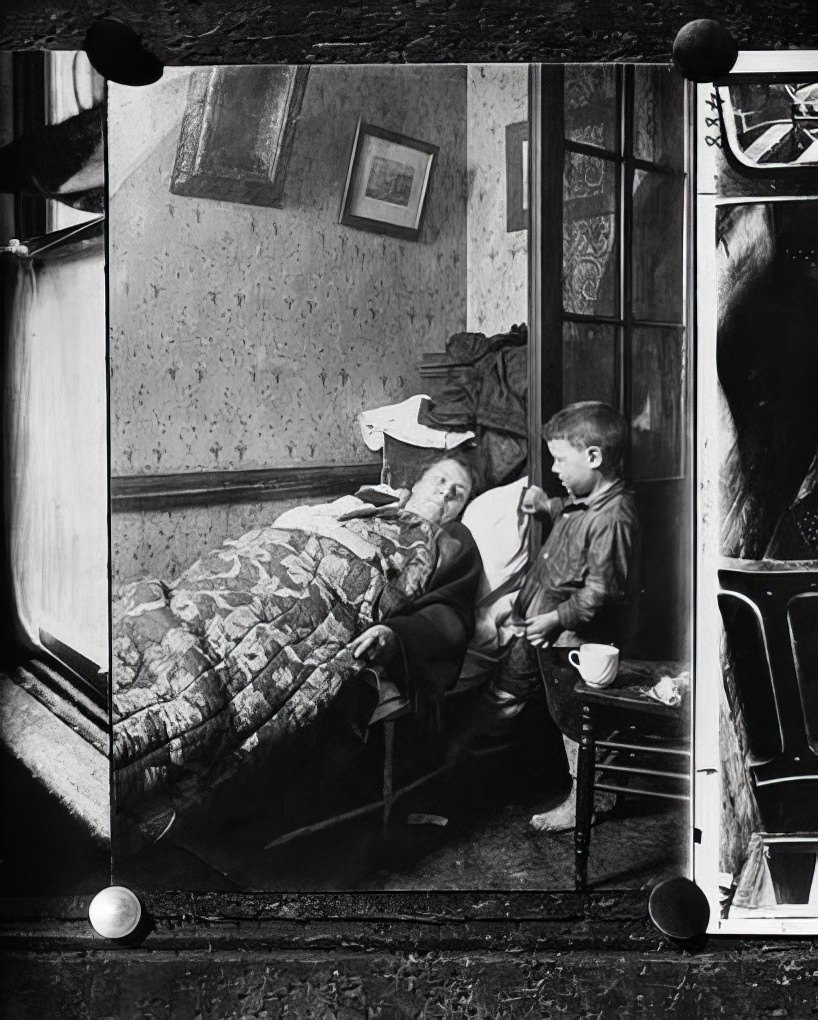

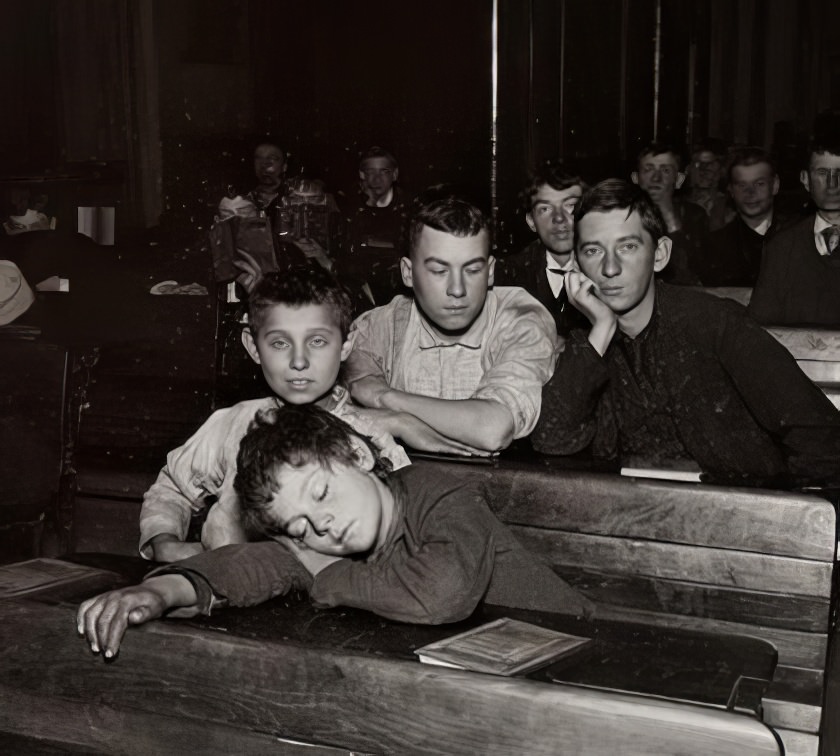

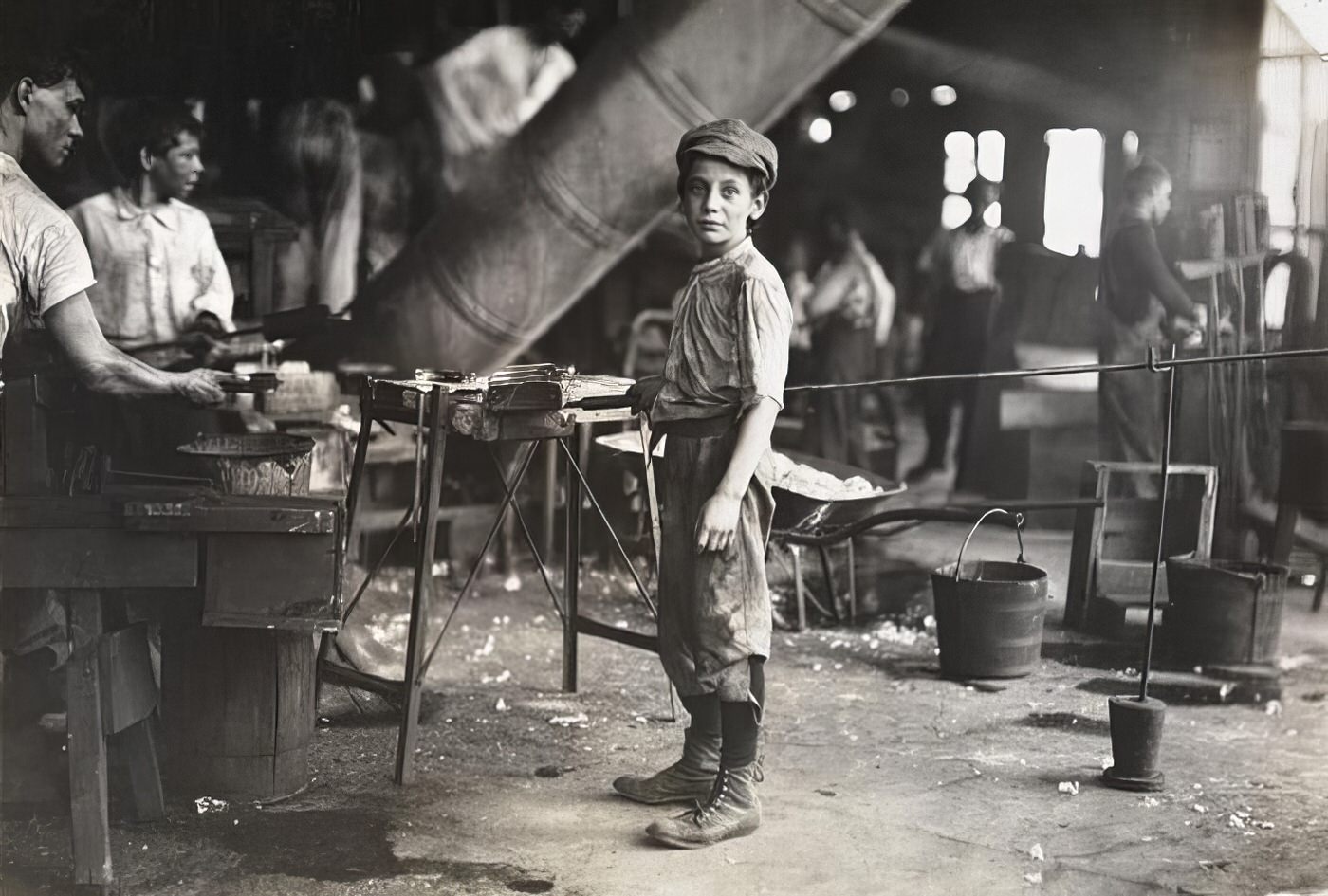

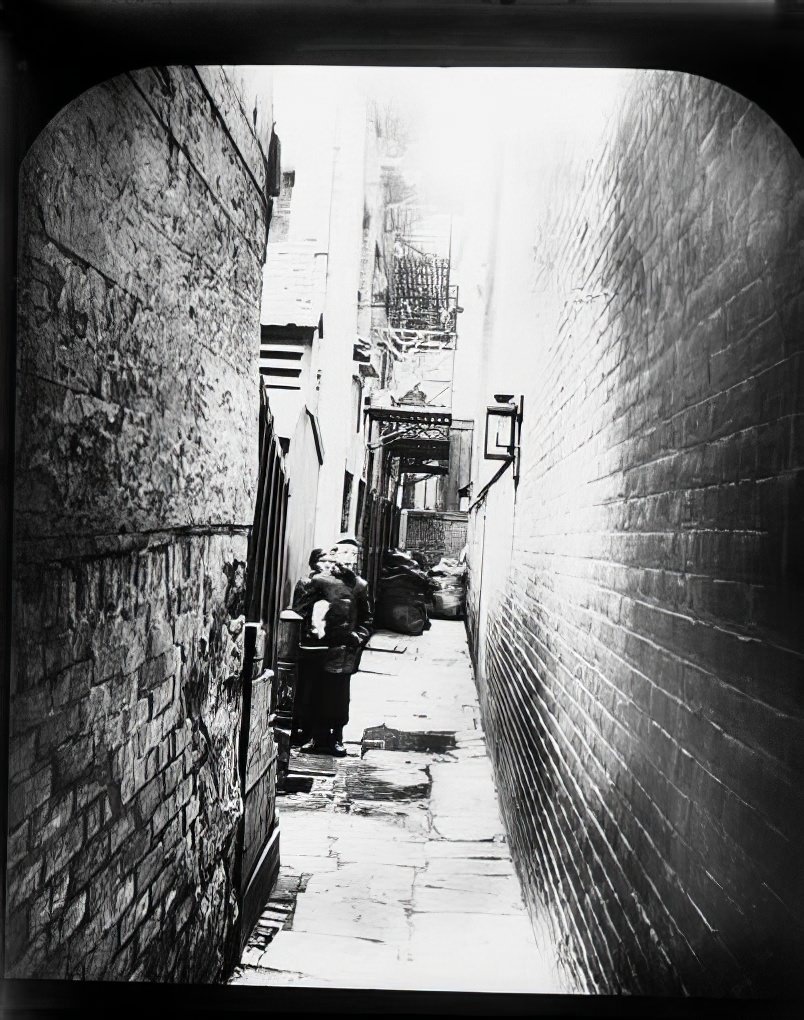

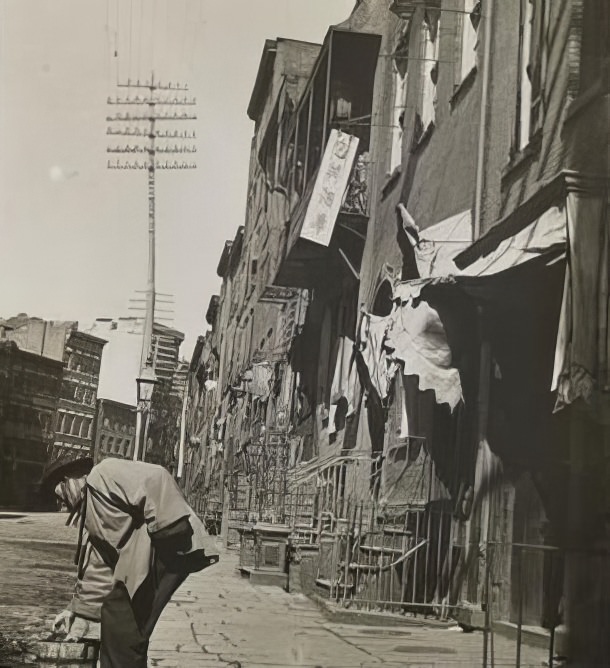

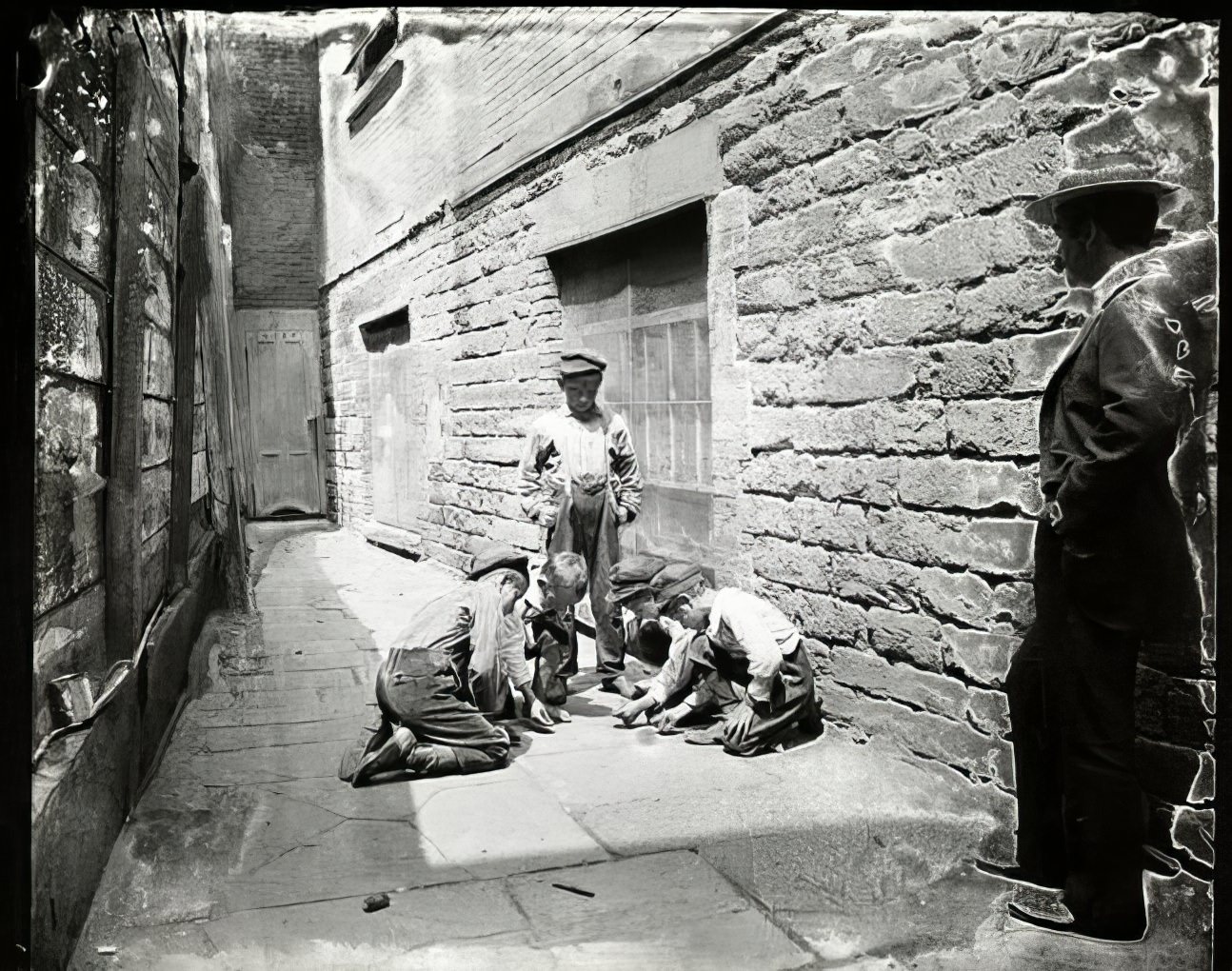

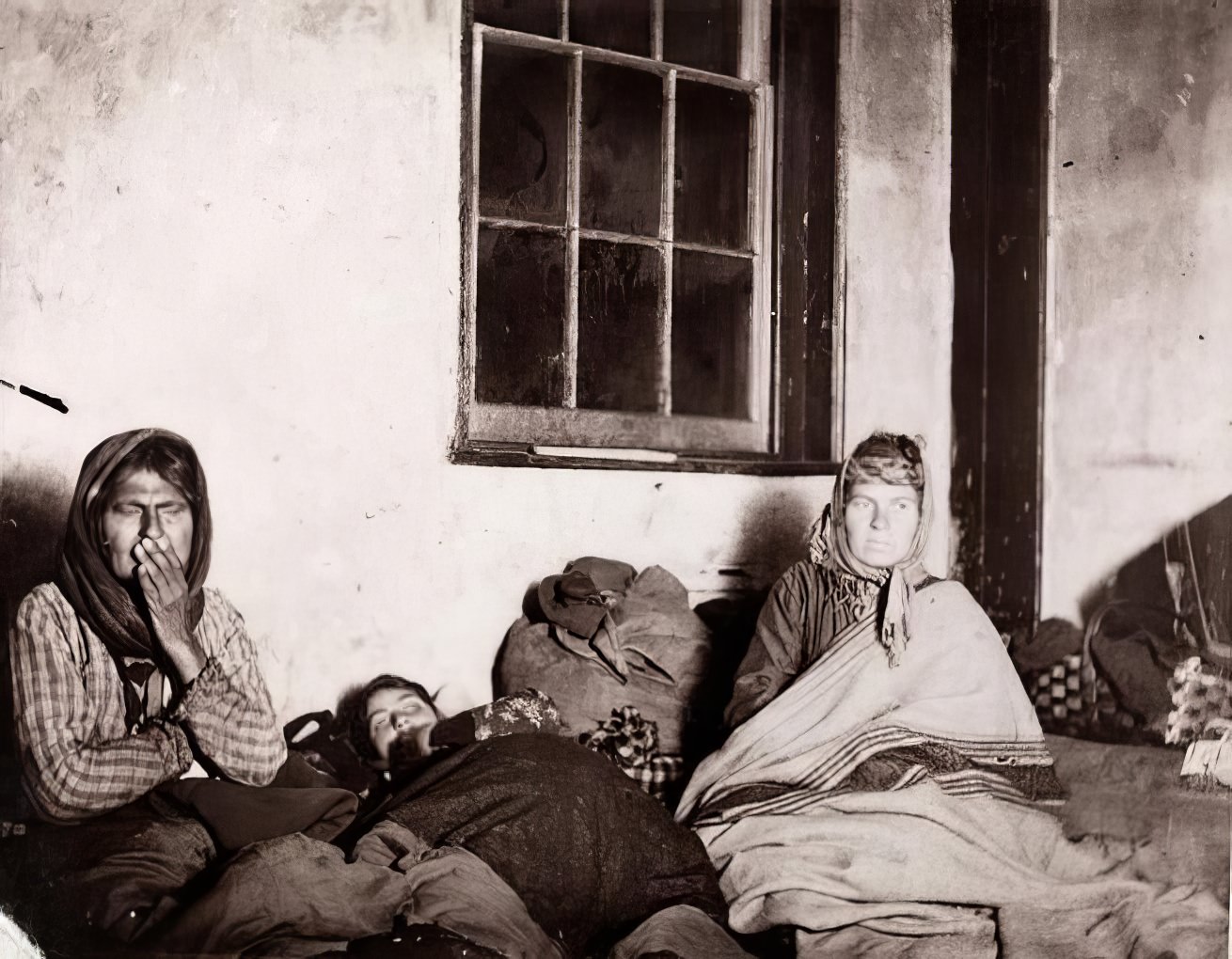

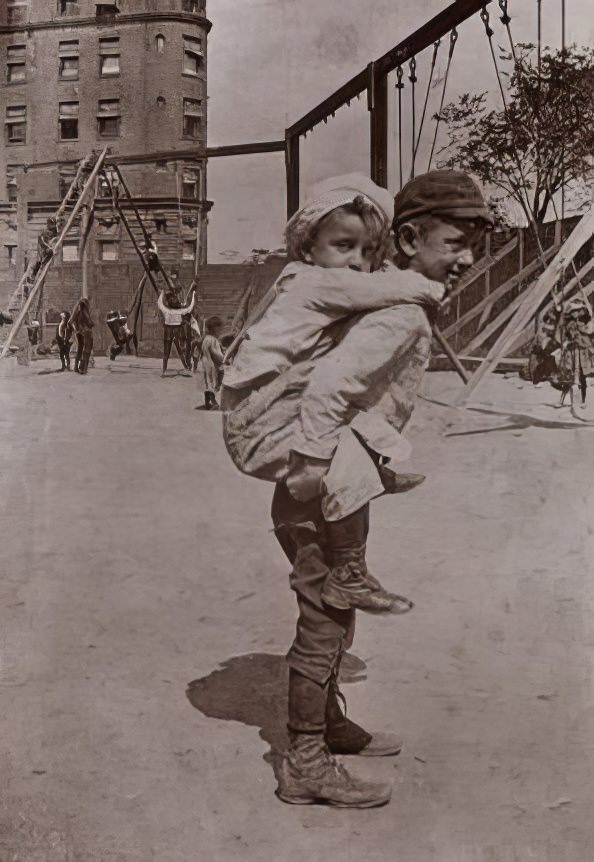

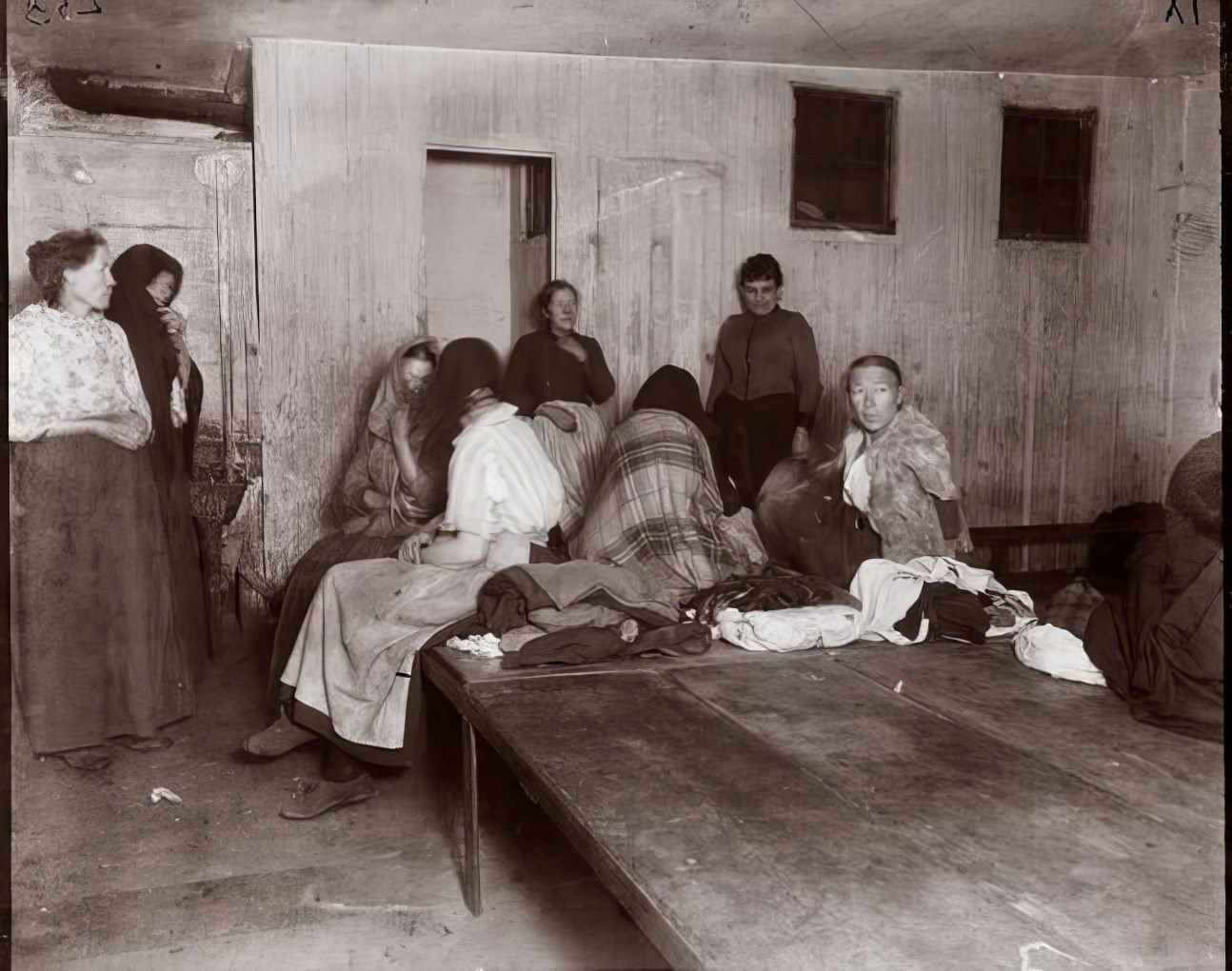

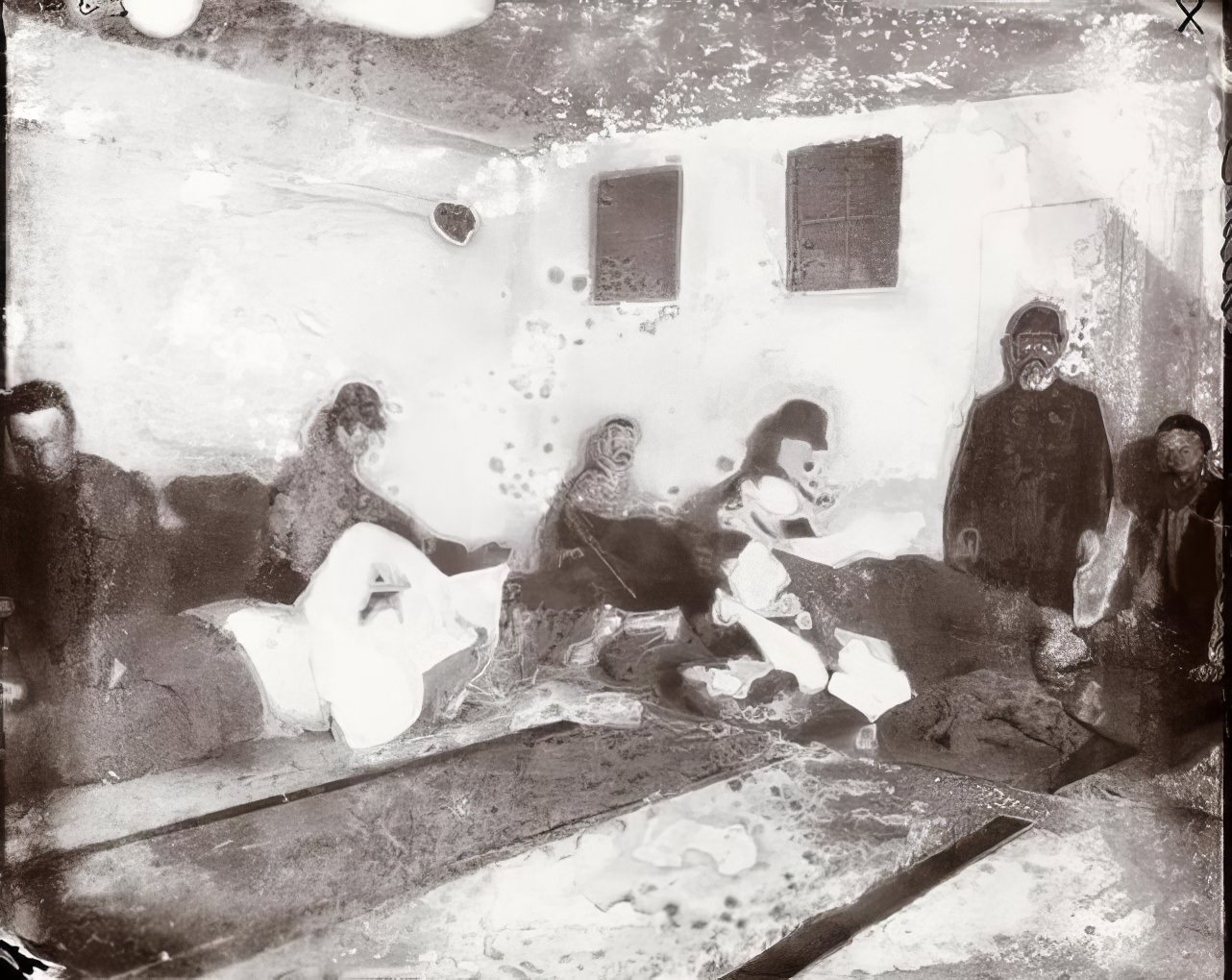

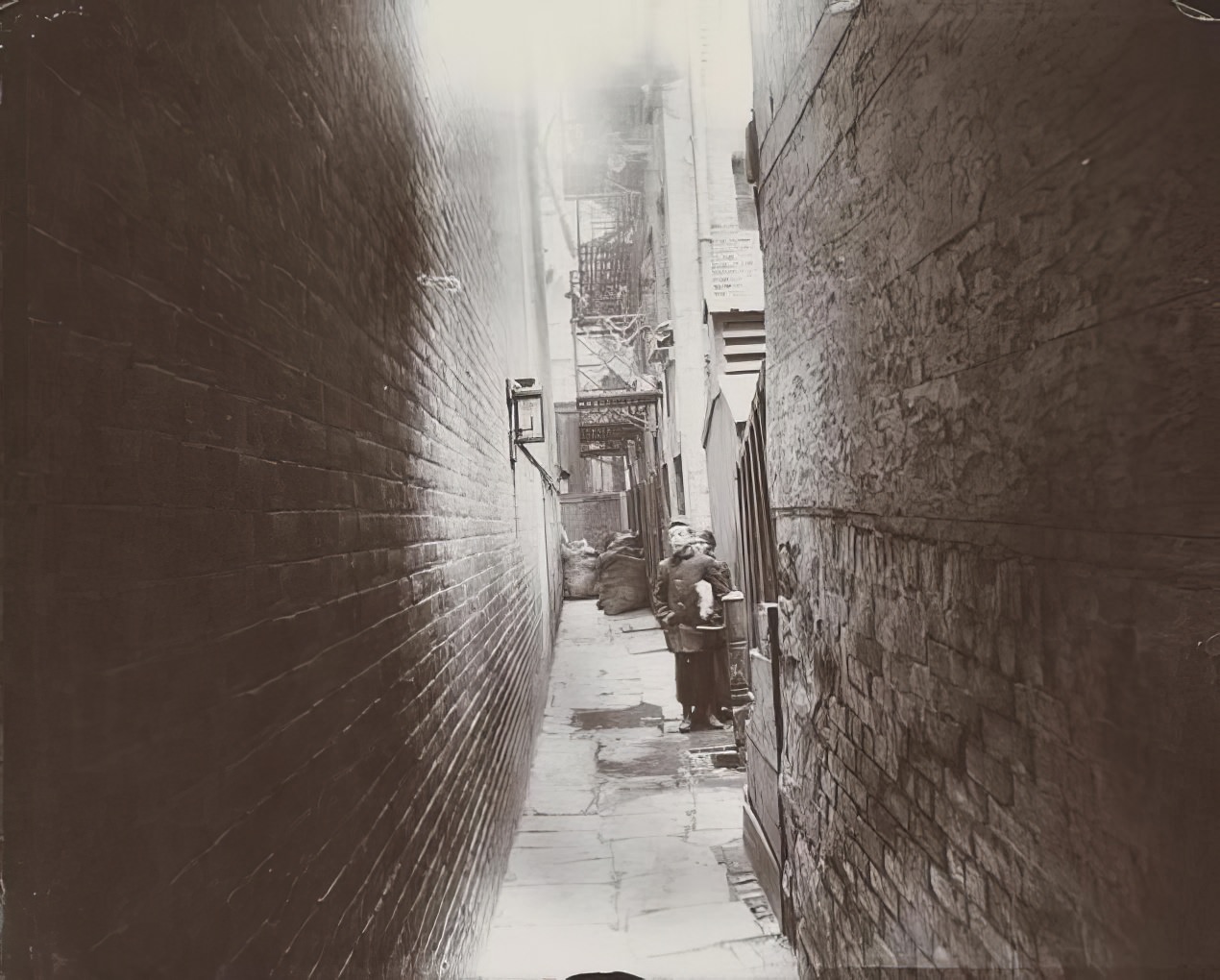

He began photographing the people and the places. He captured children sleeping in alleyways, families living in one small room, and sick people with no care. His camera showed what words alone could not. He published his work in Scribner’s Magazine in 1889. Later, he released a book titled “How the Other Half Lives.”

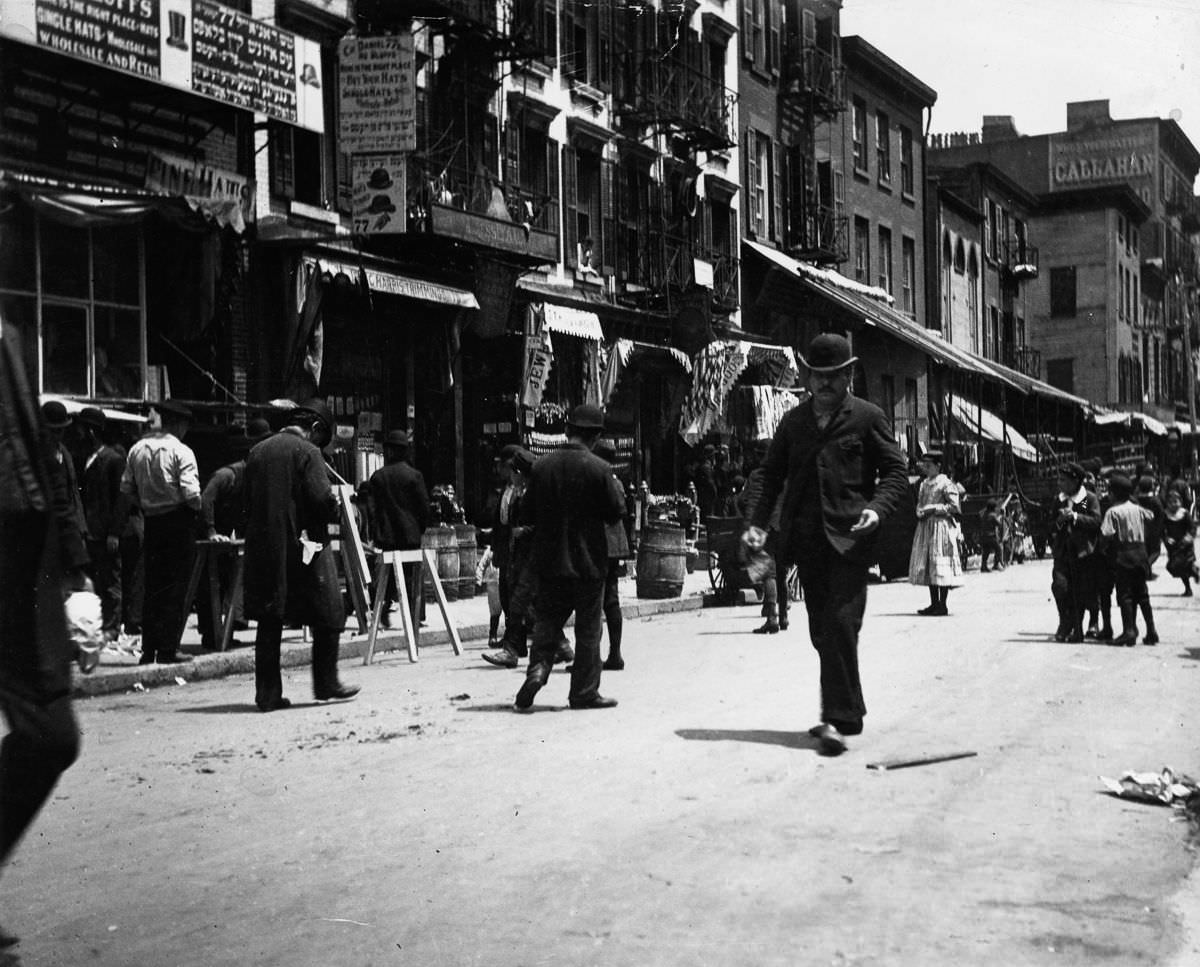

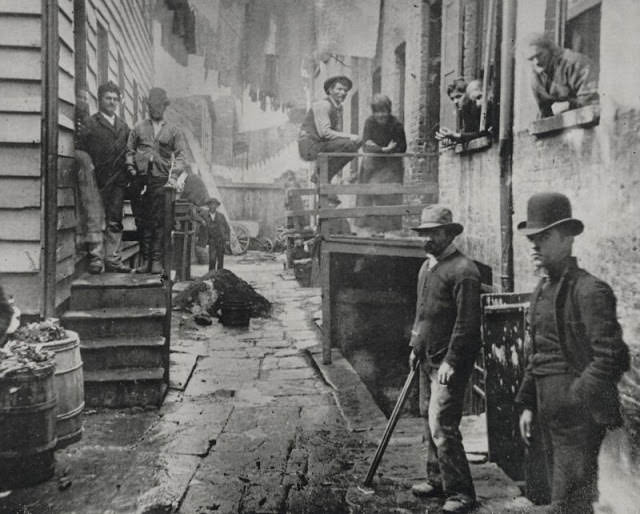

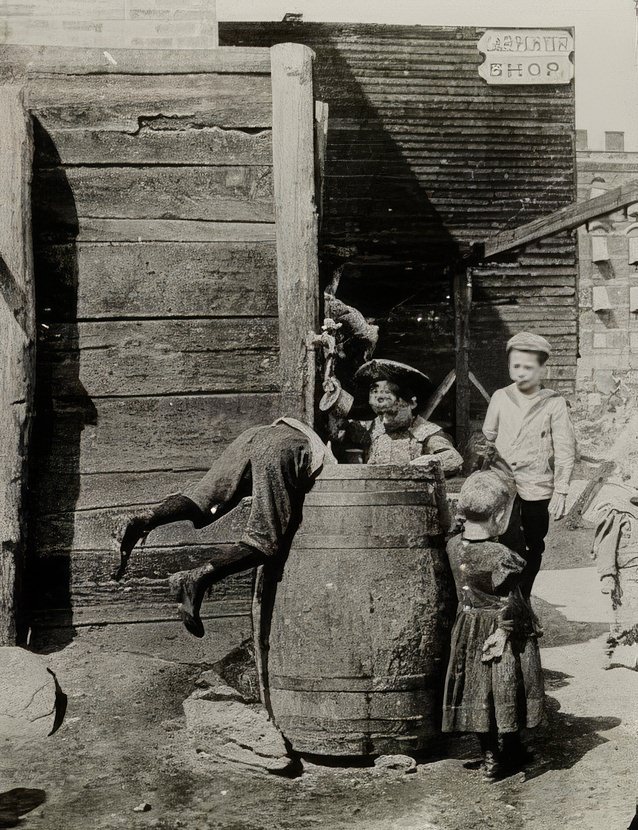

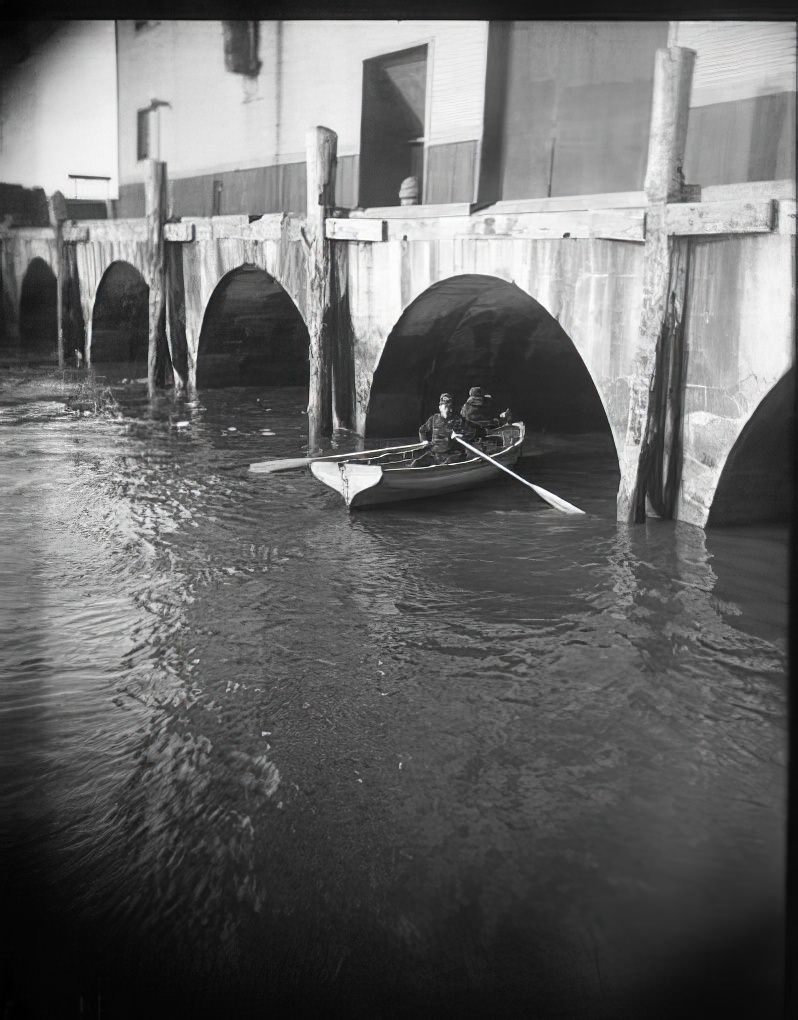

Riis wrote that over 2.3 million people were living in more than 80,000 tenements. Most of these buildings were in poor condition. In neighborhoods like Five Points, the streets were filled with trash. Open sewers ran between buildings. Disease spread quickly. Cholera, tuberculosis, and typhoid were common. Children often died young.

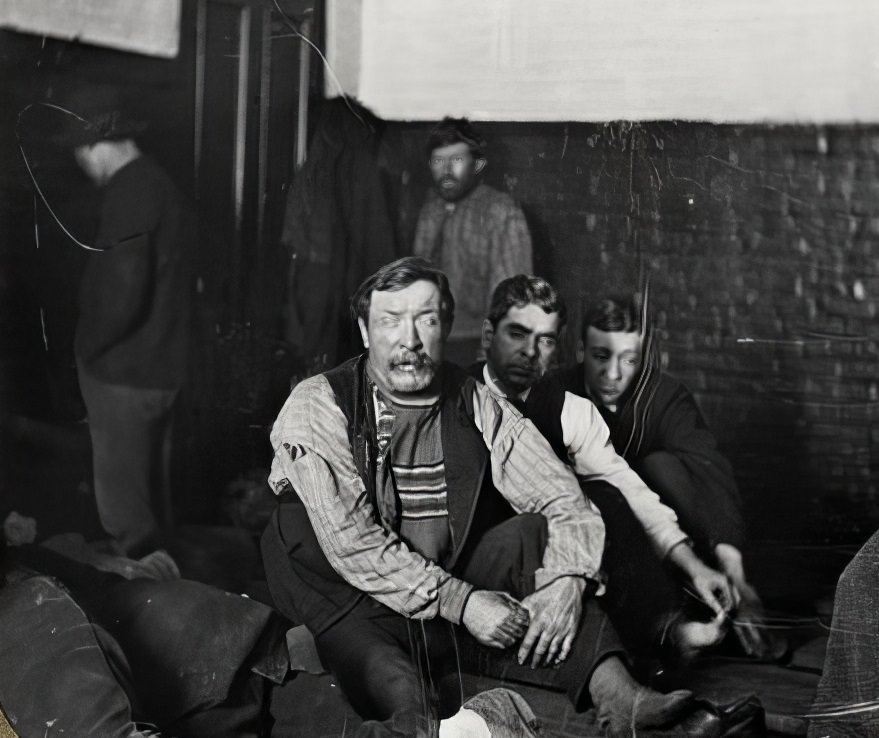

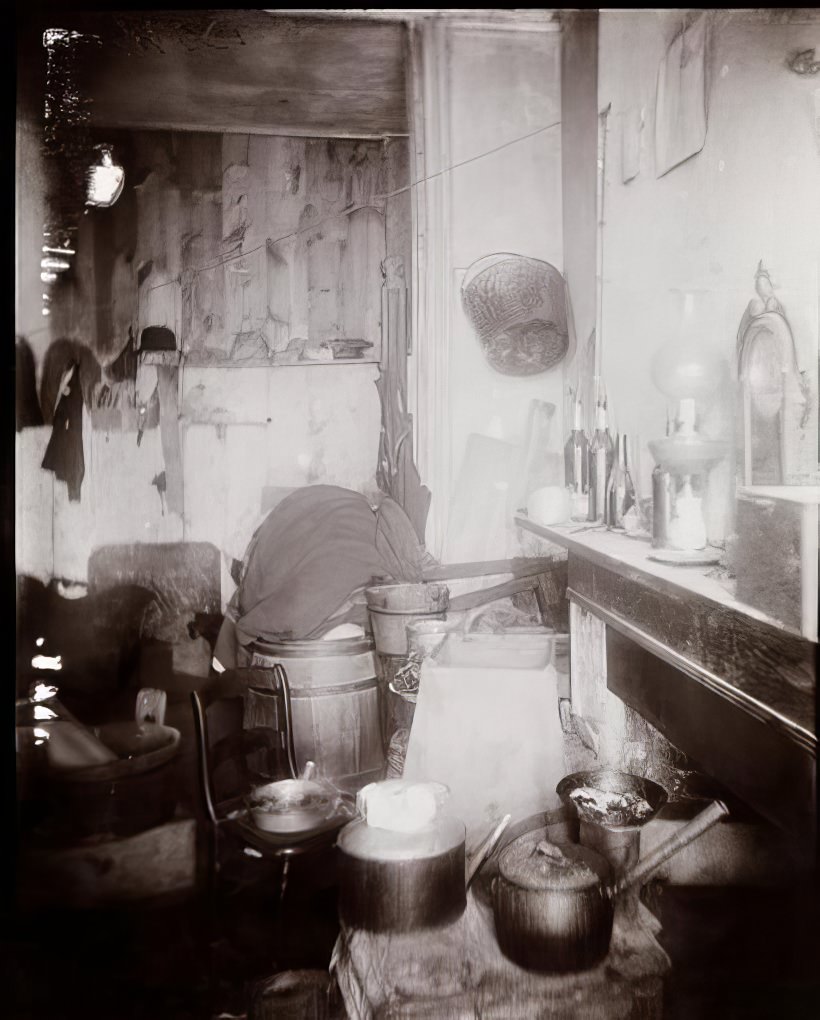

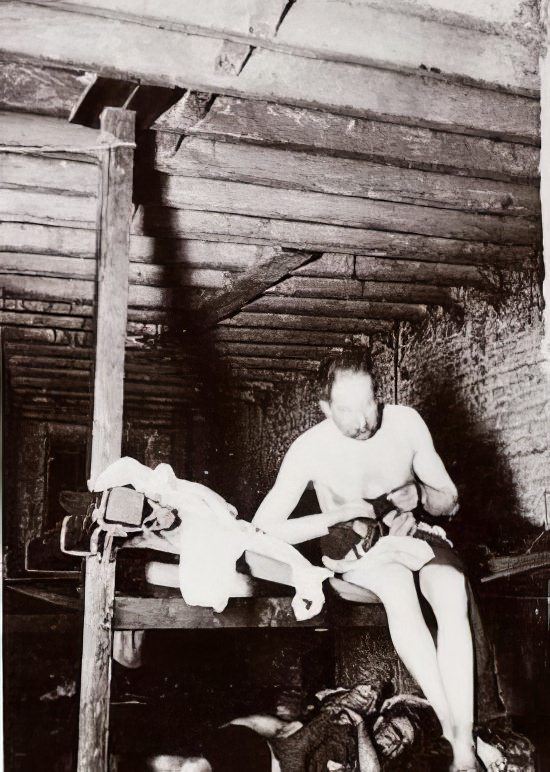

In some areas, two or three families lived in one room. Some rooms had no light at all. People used candles or gas lamps if they could afford them. In the worst cases, there were no beds. Entire families slept on piles of rags. Others lived in basements, often flooded and cold.

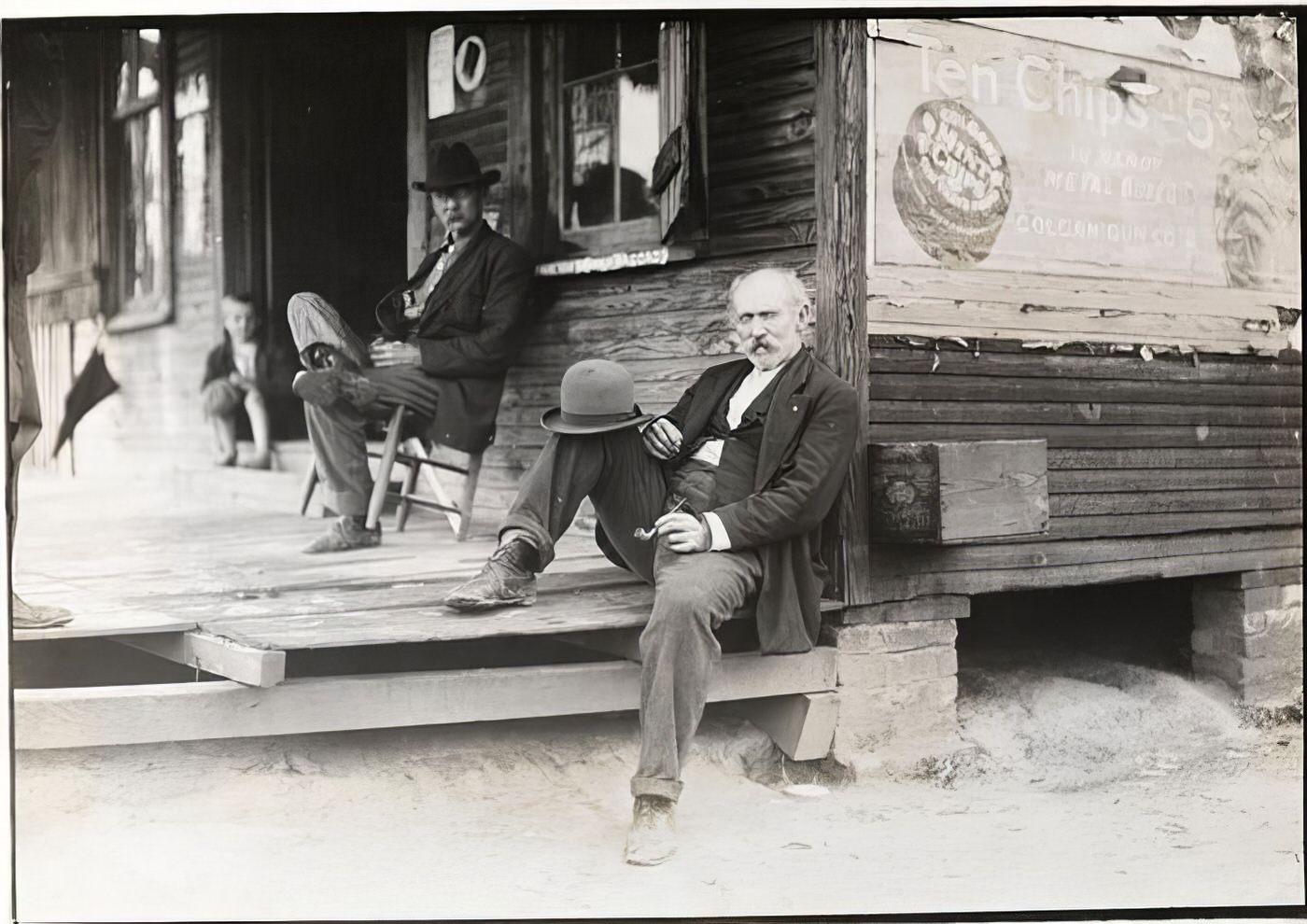

The poorest workers earned less than $10 a week. That money had to cover rent, food, and clothing. Rent was usually high, even for terrible spaces. Landlords did not make repairs. If tenants complained, they risked eviction. There were no housing laws to protect them.

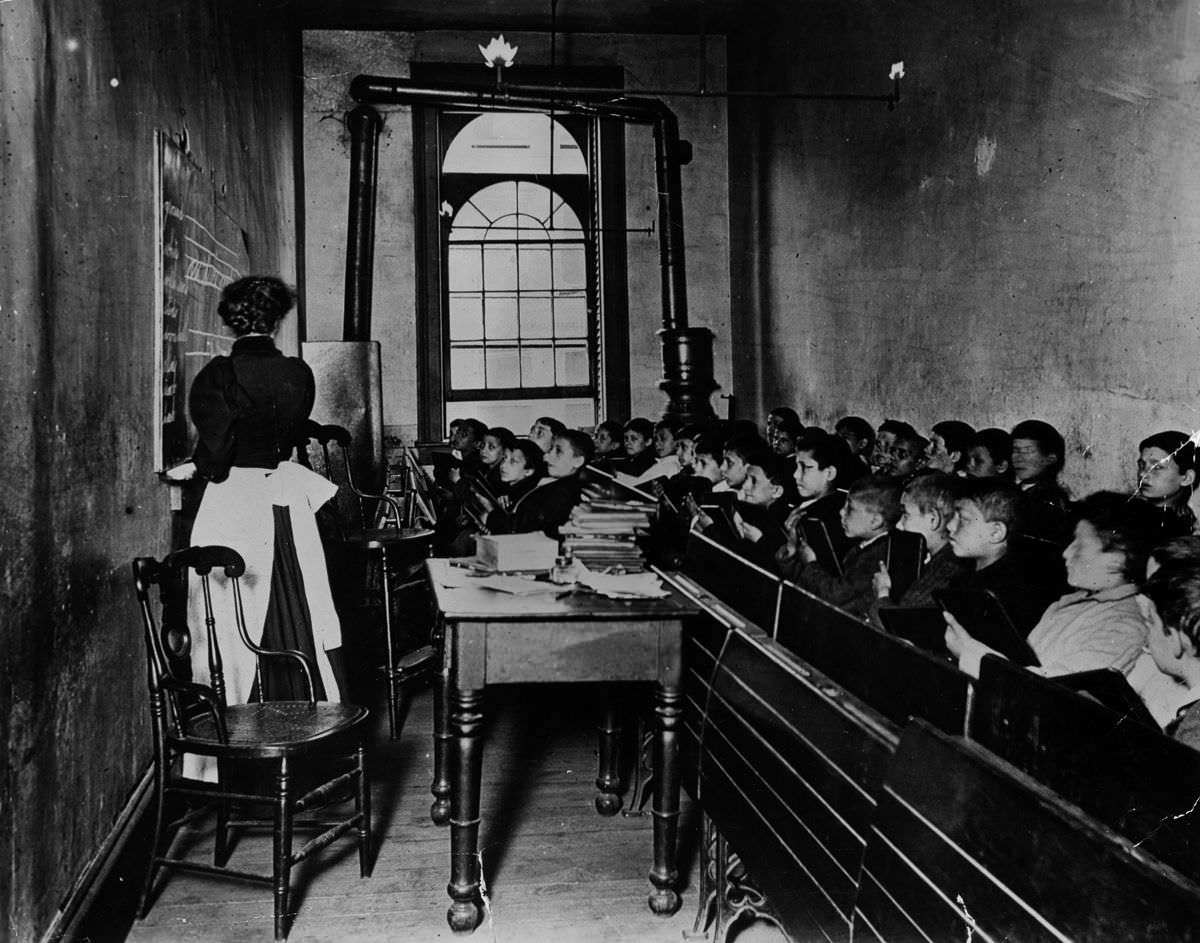

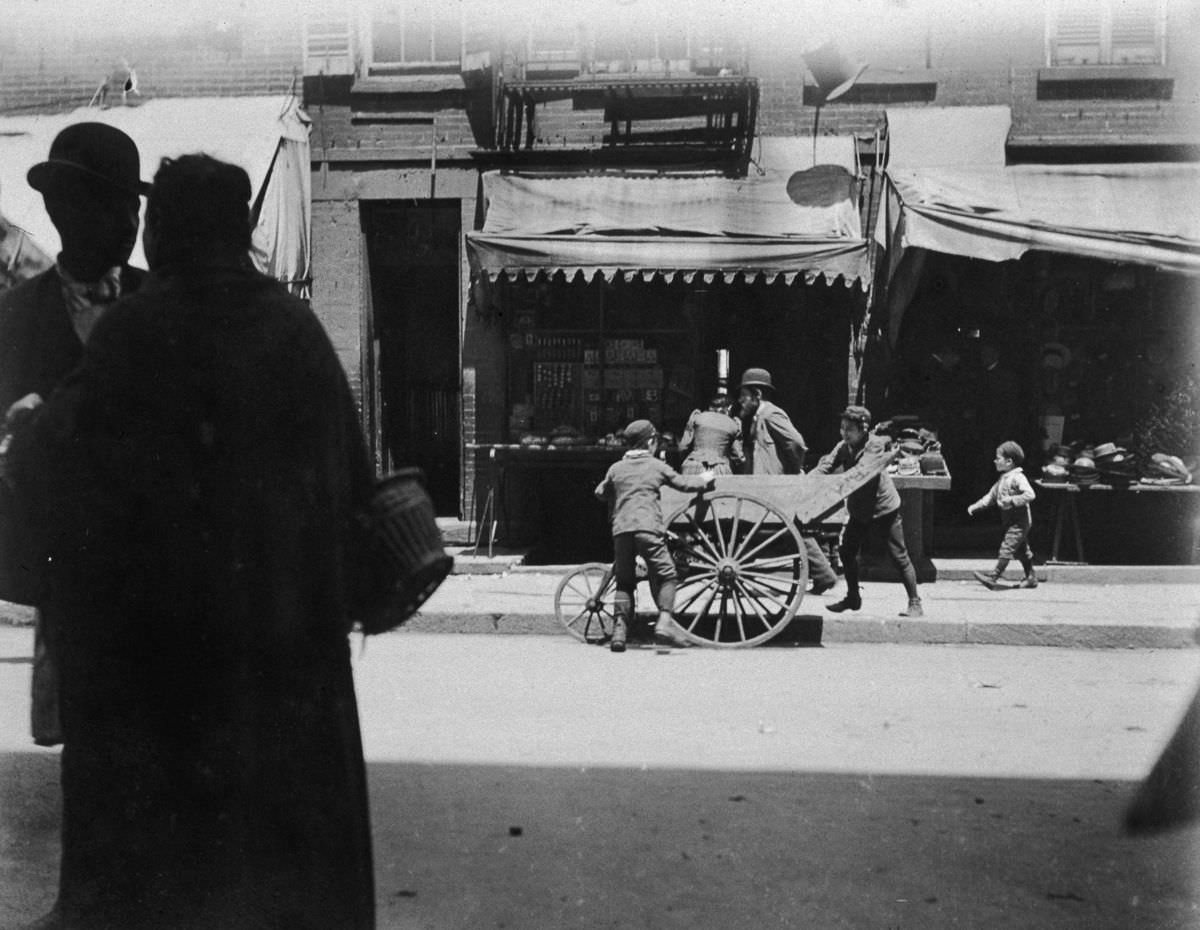

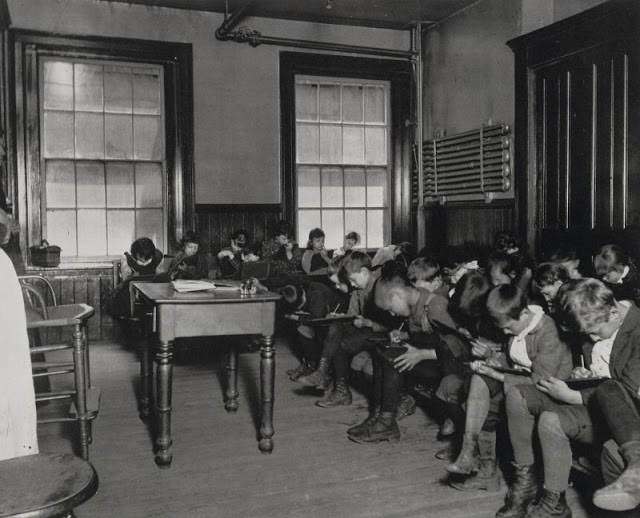

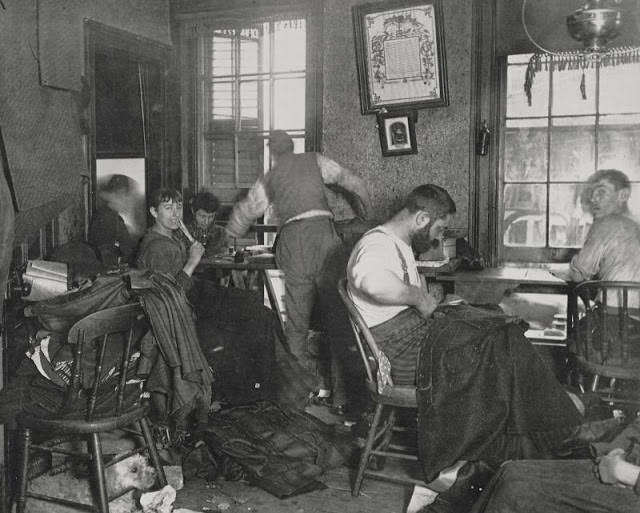

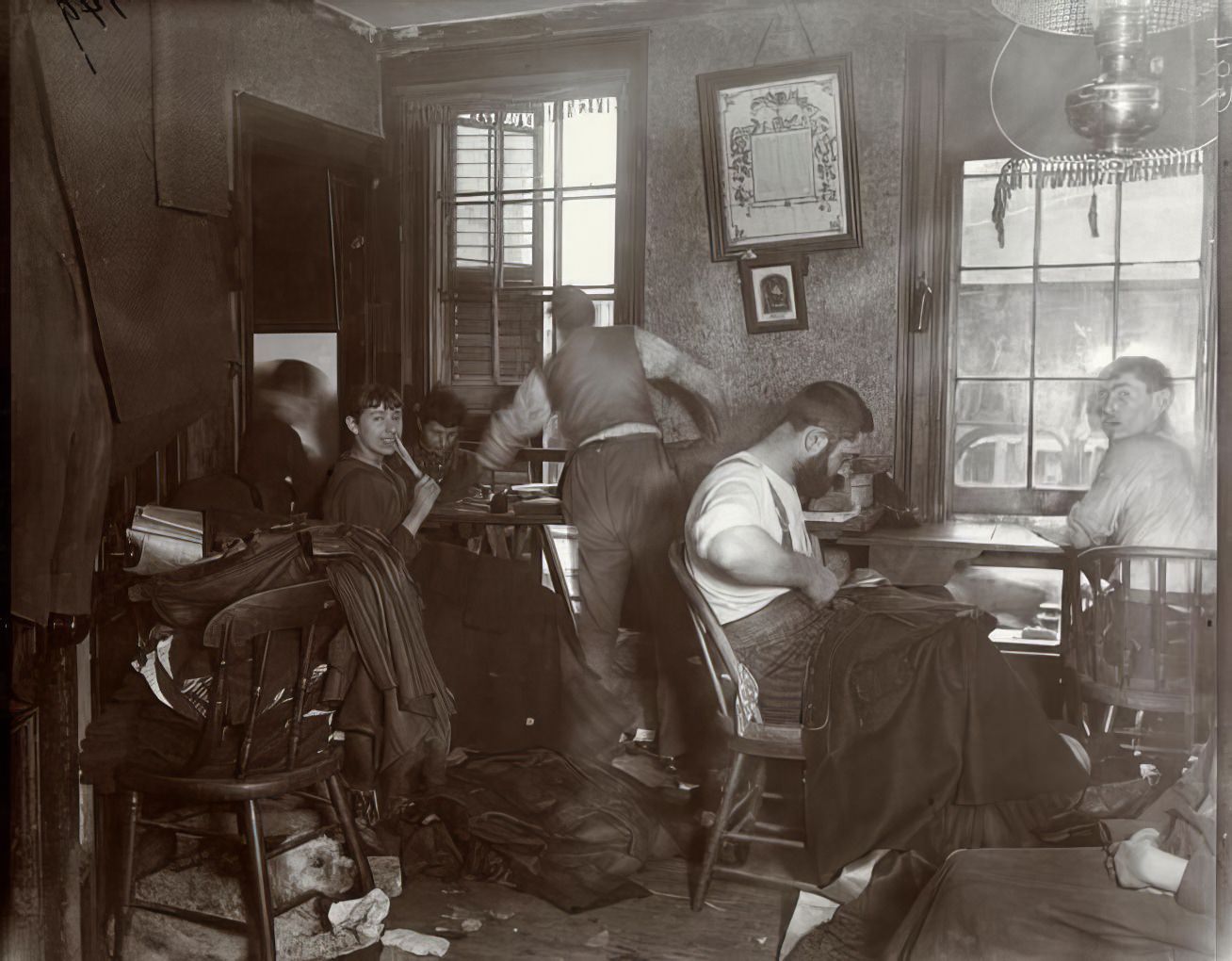

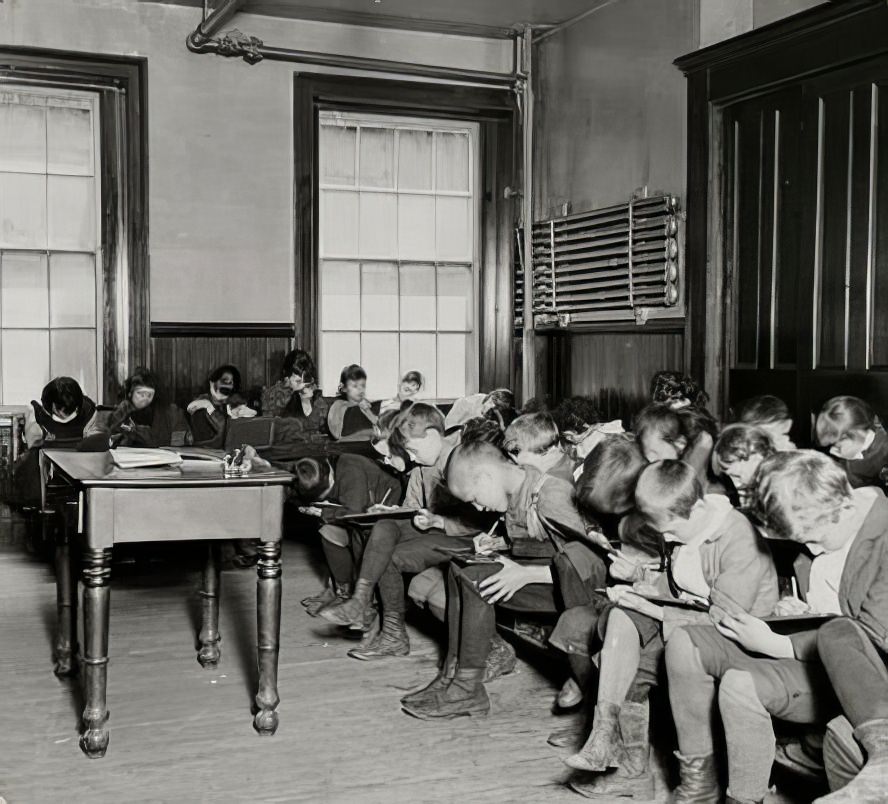

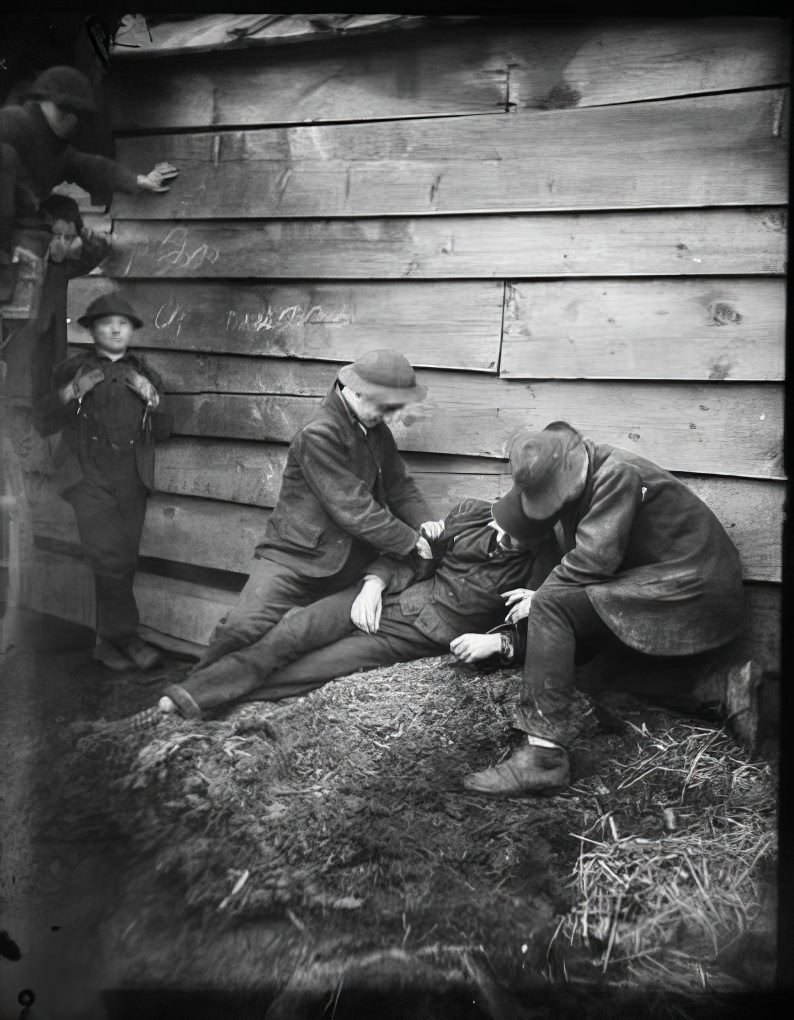

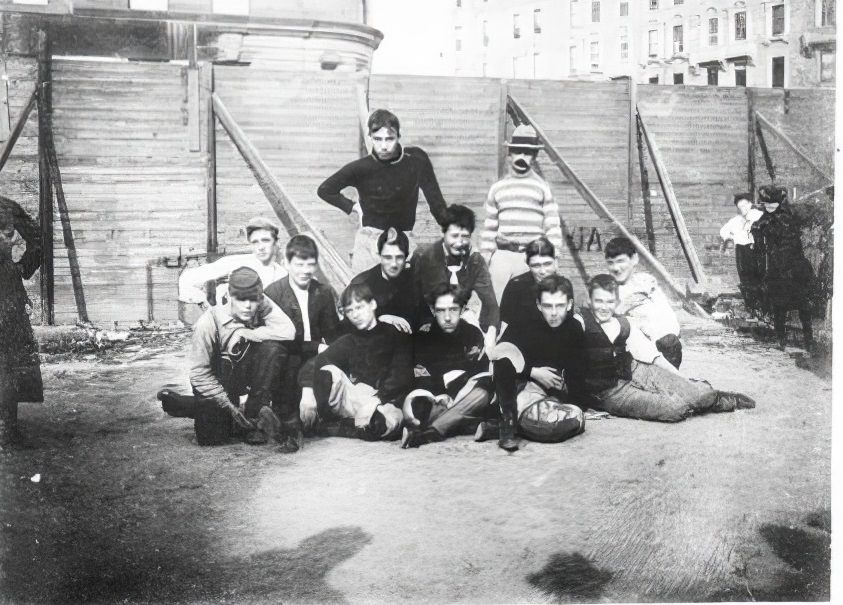

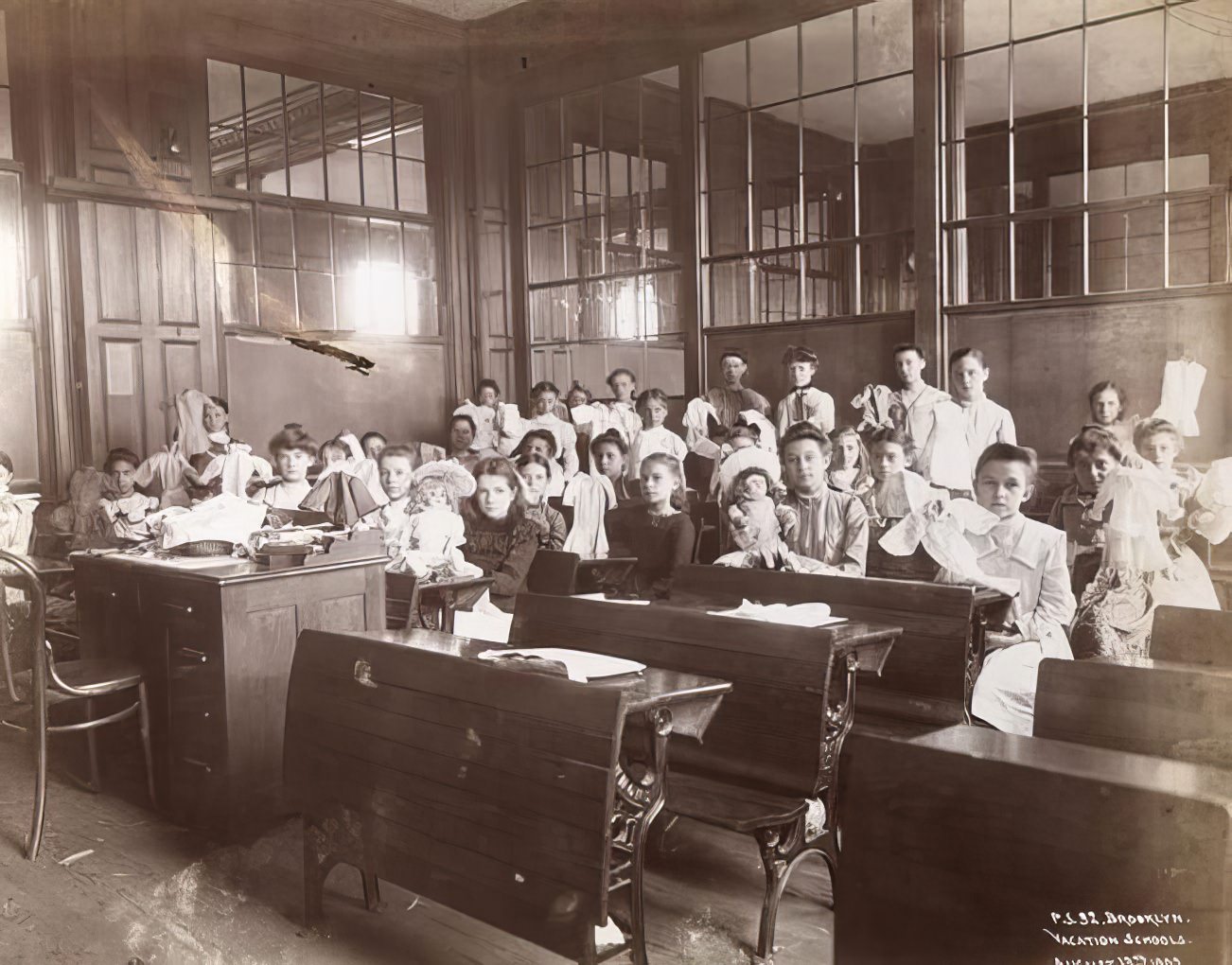

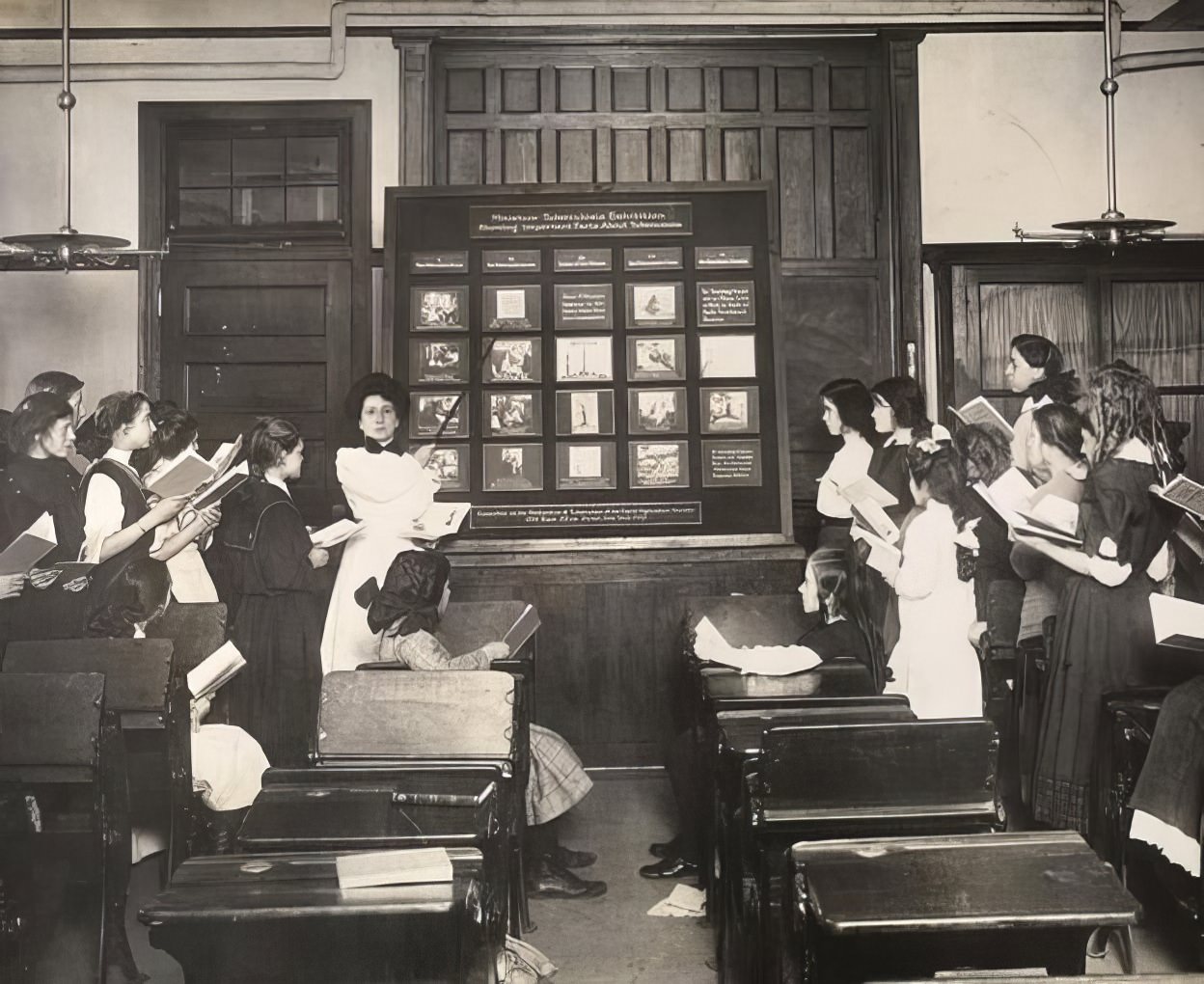

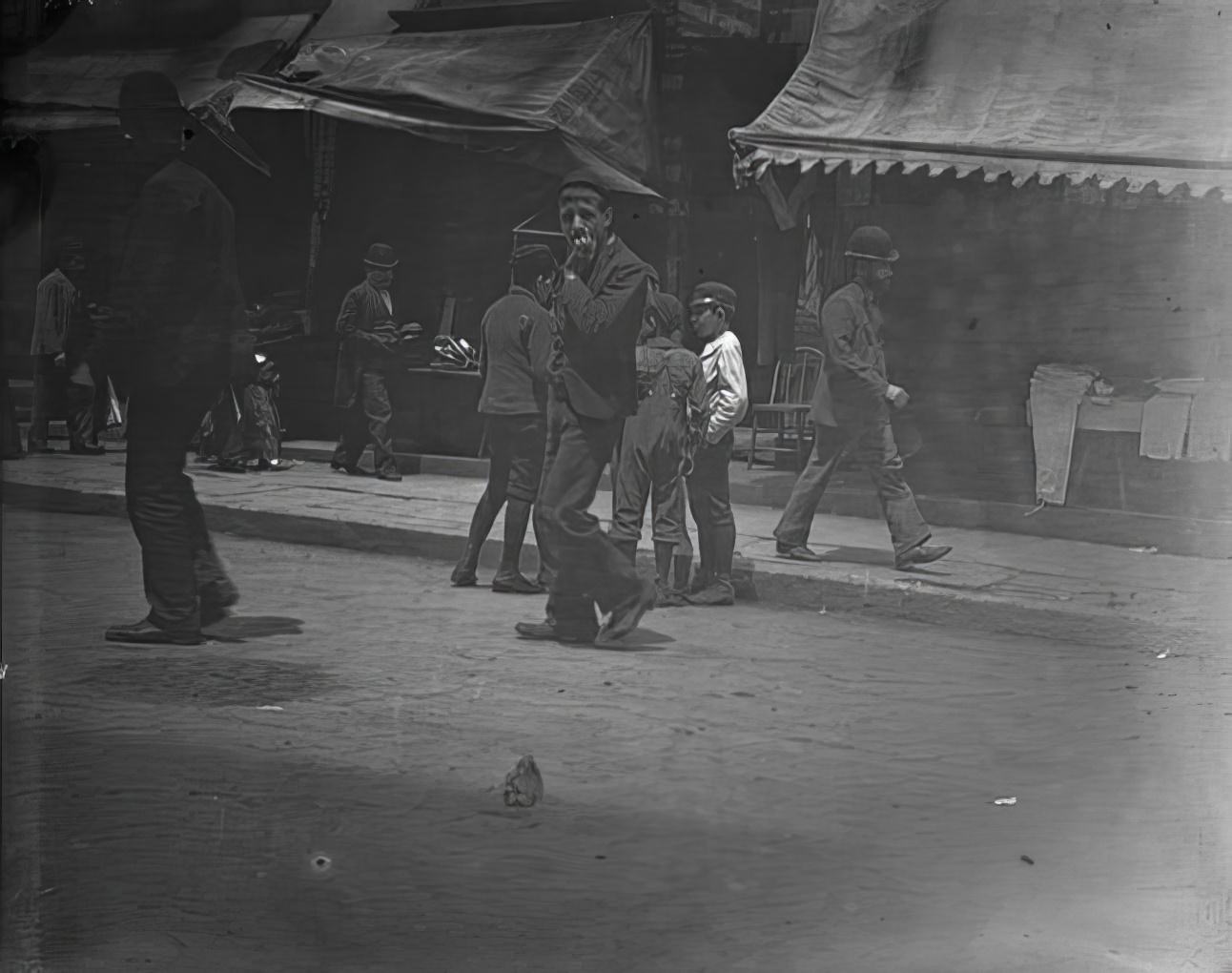

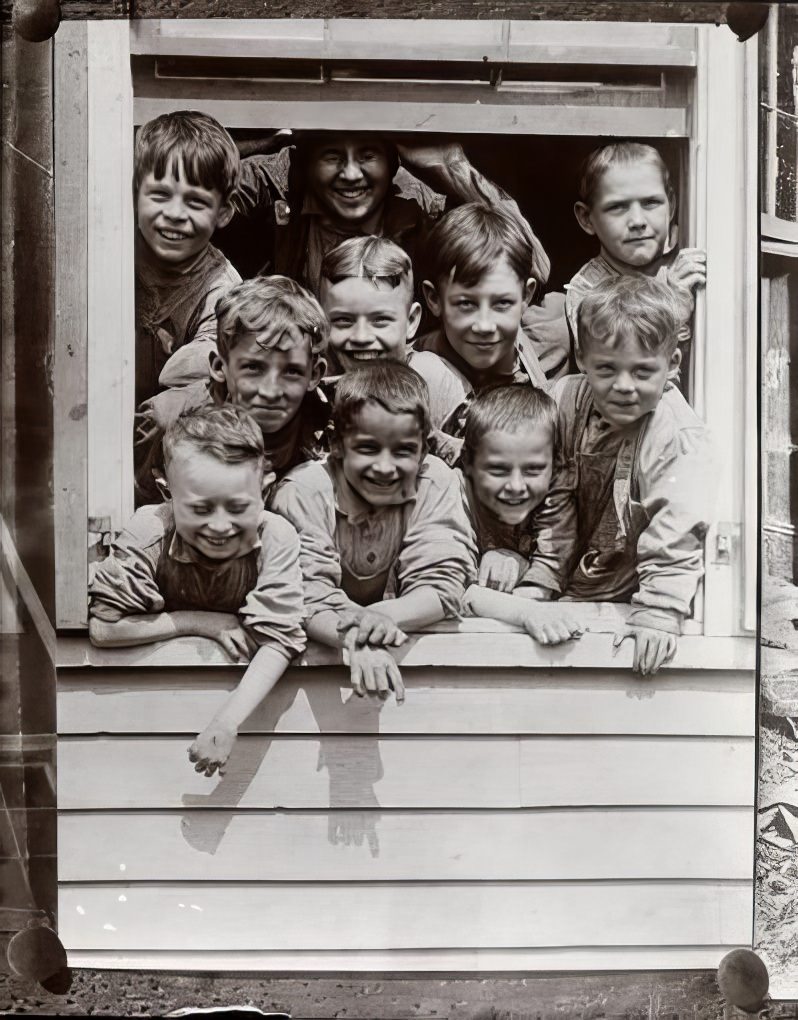

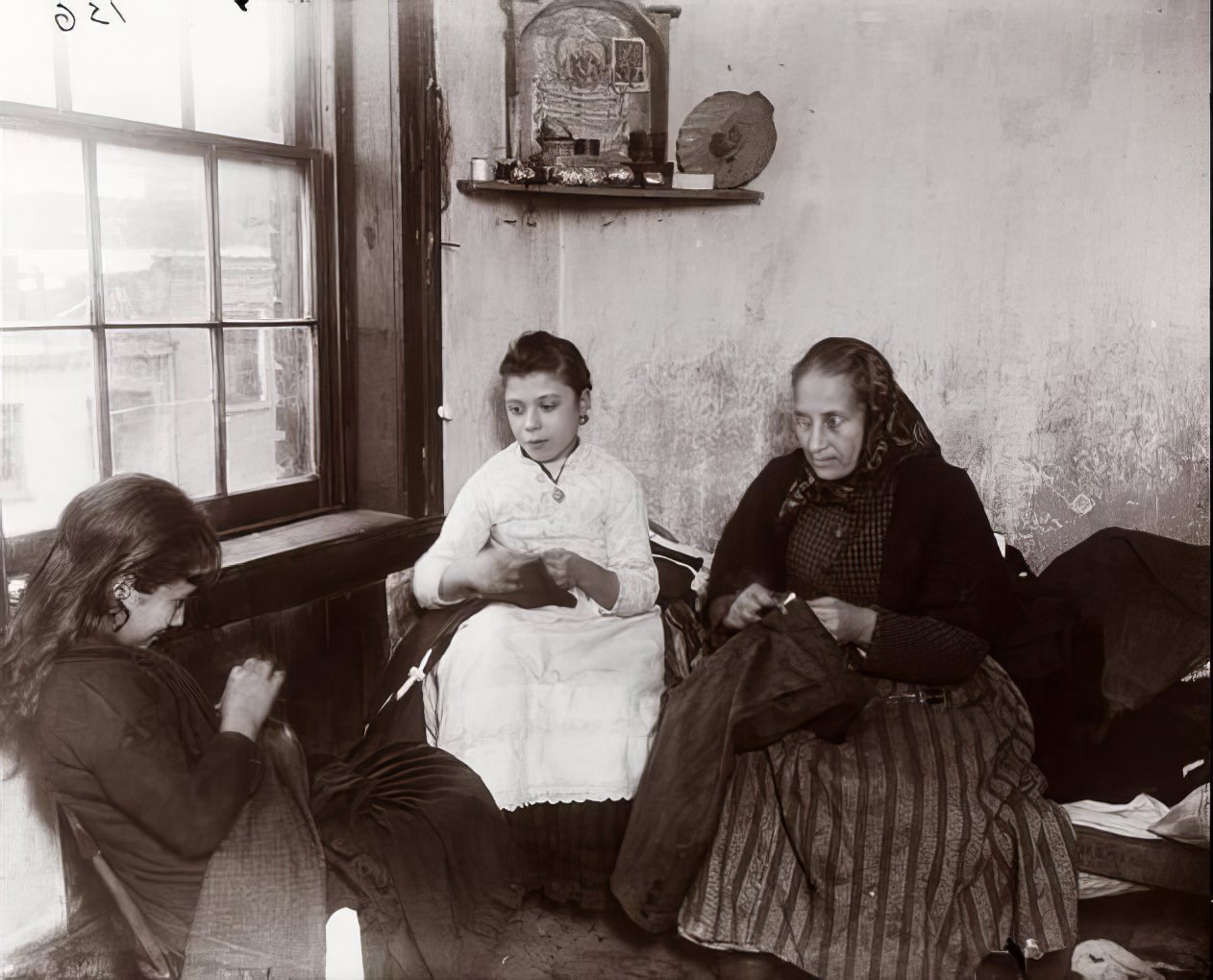

Children worked as soon as they could walk. Boys sold newspapers or shined shoes. Girls worked in factories or took care of younger siblings. School was a luxury. Many families needed every member to bring in money. Adults worked long hours in factories, sweatshops, and on the streets.

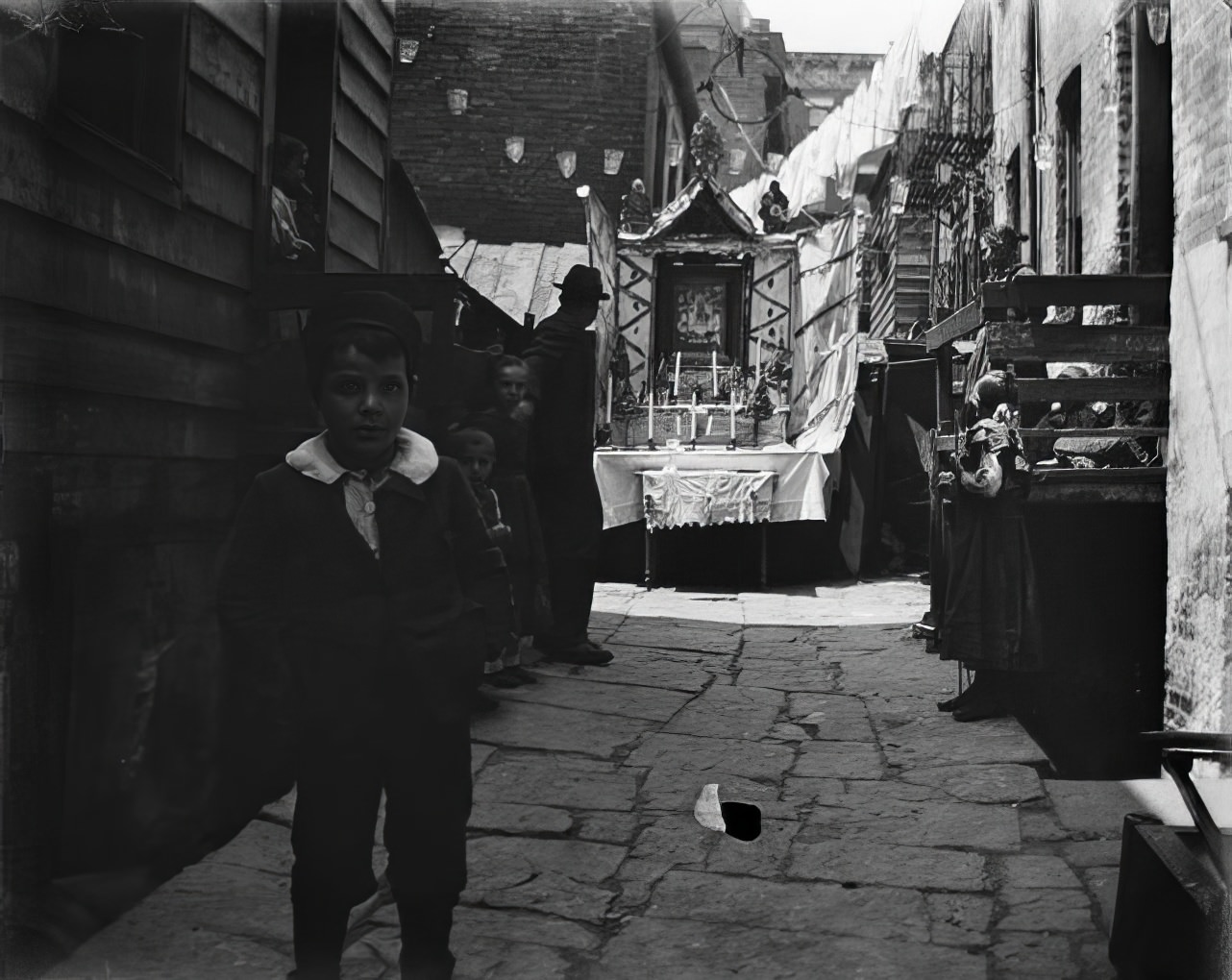

Many immigrant groups stayed in their own communities. Italians lived near other Italians. Jewish families stayed close to their synagogues. Each group brought their own customs and languages. This created busy, crowded neighborhoods full of shops, food carts, and markets. Despite poverty, these areas were rich in culture.

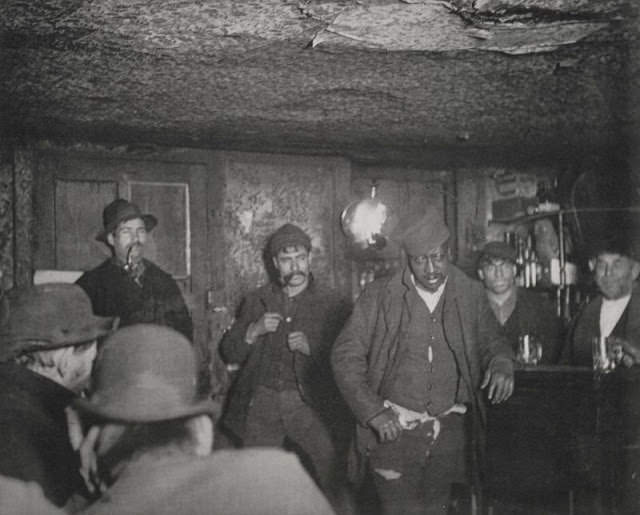

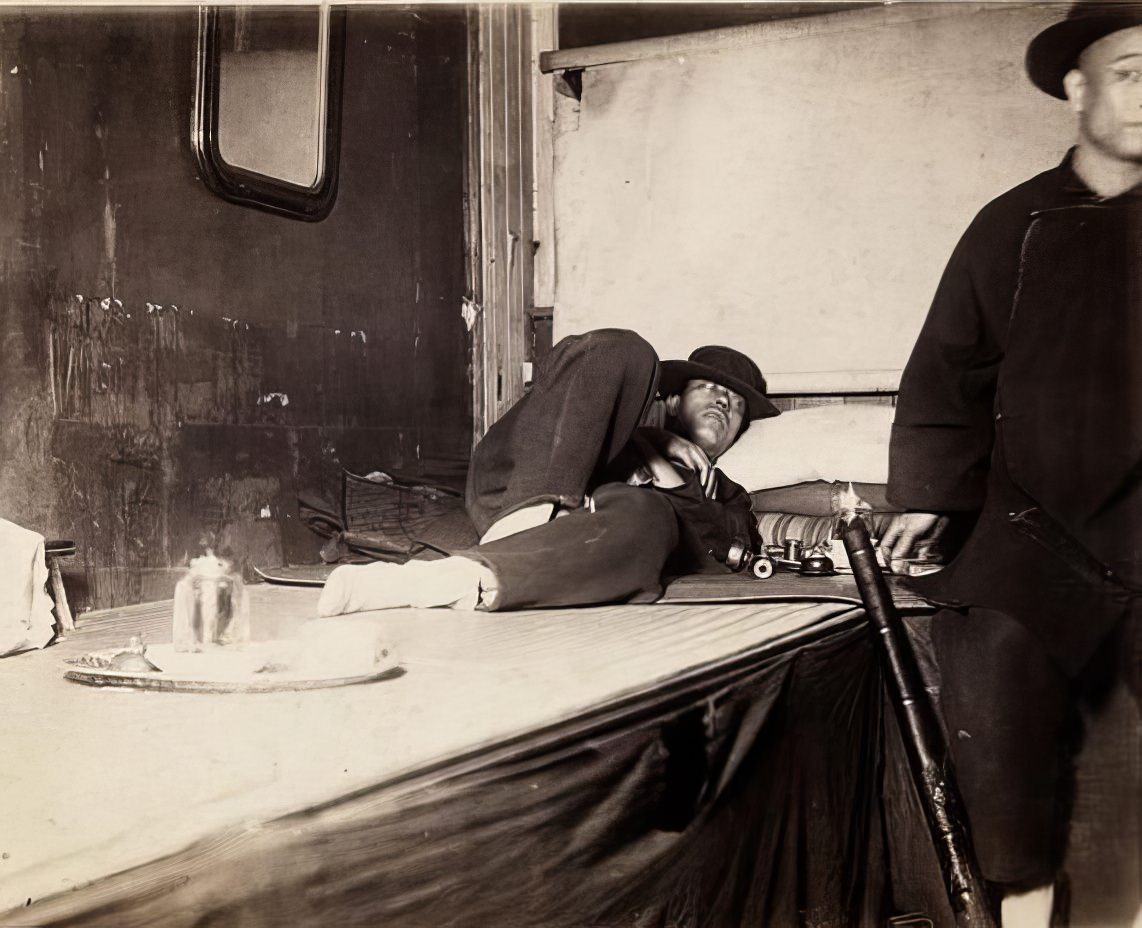

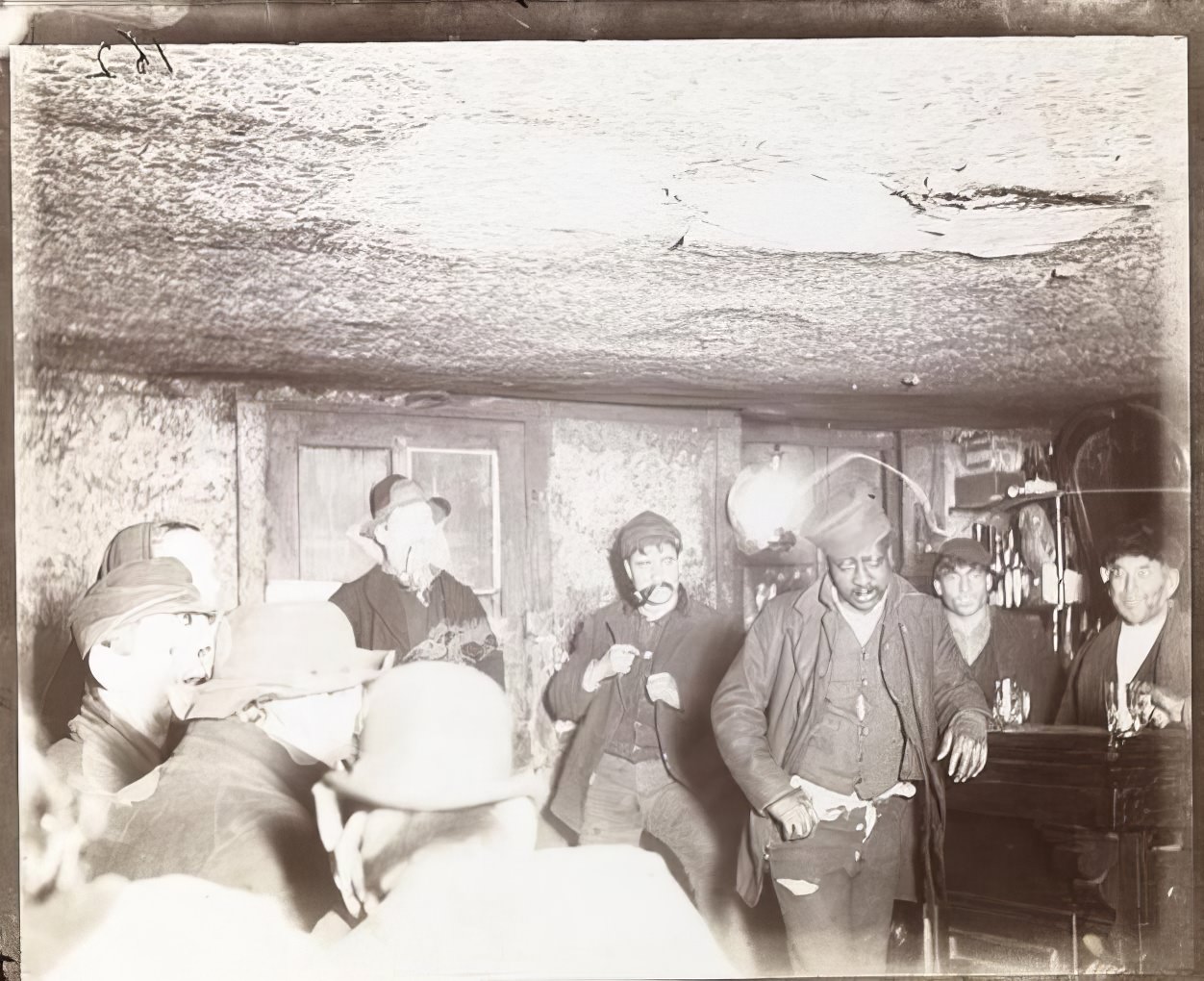

Riis used flash photography, a new technique at the time. It allowed him to photograph dark interiors. He walked into the worst buildings at night with police escorts. He often surprised people with his camera flash. This shocked the public when the photos were published. Most middle- and upper-class New Yorkers had never seen how the poor lived.

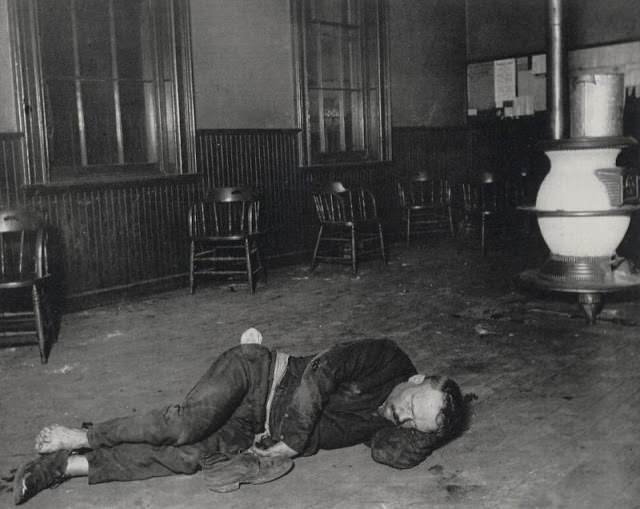

Alcohol was a major problem in the slums. Many men spent their few coins on drink. Taverns were crowded day and night. Domestic violence and neglect were common. Women were often left to raise children alone. Some turned to begging or sex work to survive.

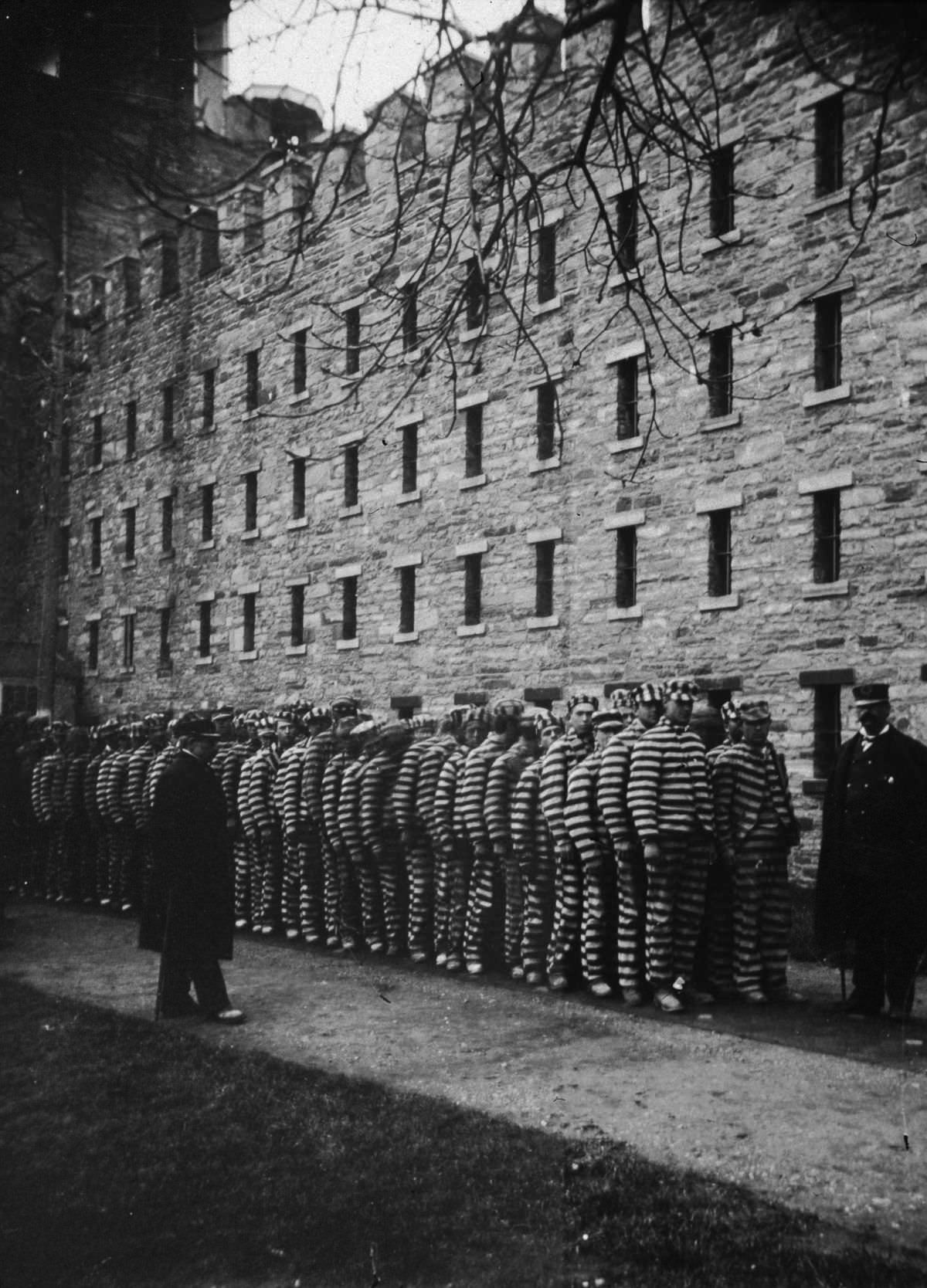

The police were present but often corrupt. Officers took bribes or ignored crimes. Riis saw this during his investigations. He showed how law enforcement failed the poor. In some cases, police helped landlords evict tenants who could not pay.

Factories and sweatshops filled every available space. It was not unusual for sewing machines to be set up in the same room where families slept. Long hours, low pay, and unsafe conditions were standard. Injuries and illness went untreated.

The smell of the tenements was unforgettable. There was the scent of rotting food, human waste, sweat, and smoke. Rats and cockroaches were everywhere. Garbage piled up on the streets. There were few trash services, and no one took responsibility for cleanup.

Women carried heavy burdens. They washed clothes by hand, cooked meals, and cared for children while often working for extra income. Many took in laundry or sewed clothing for shops. They had little help or rest.

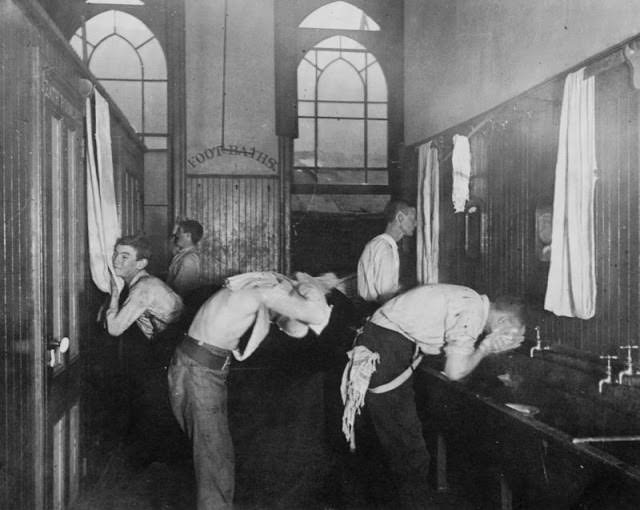

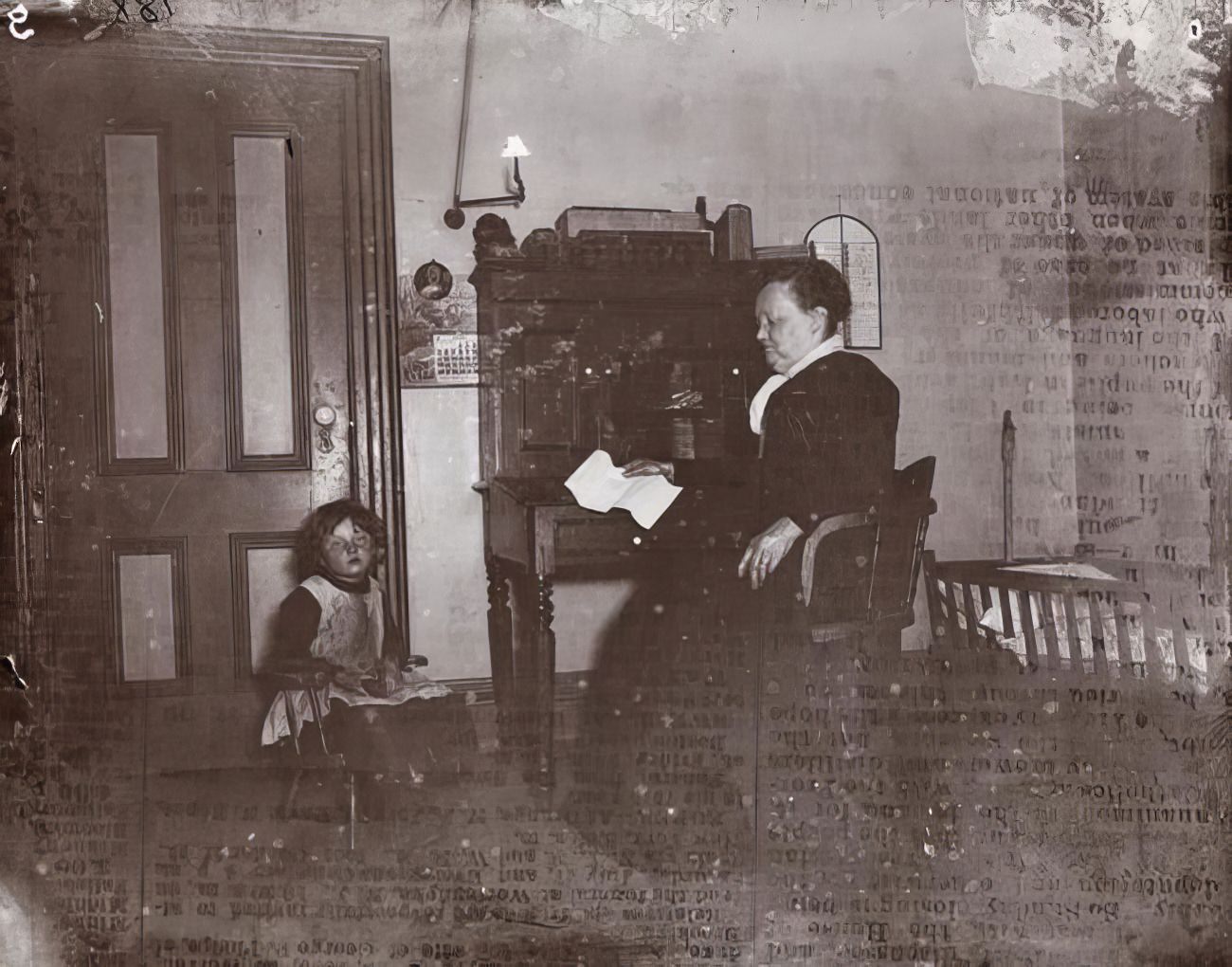

Some religious and charity groups tried to help. Churches opened soup kitchens and shelters. Volunteers visited sick families. These efforts were small compared to the size of the problem. Riis believed in hard work and personal responsibility, but he also pushed for laws to improve housing.

Five Points was one of the worst slums. It had once been a pond, filled in during the early 1800s. The ground was soft and the buildings on it sank and cracked. By the 1850s, it was home to gangs, crime, and extreme poverty. By the late 19th century, it was still one of the city’s most dangerous places.

Riis continued to speak and write about slum life. He worked with city leaders to make changes. He guided police and politicians through the neighborhoods. He believed showing the truth could bring reform. Theodore Roosevelt, then the city police commissioner, supported his work. They walked the tenements together.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings