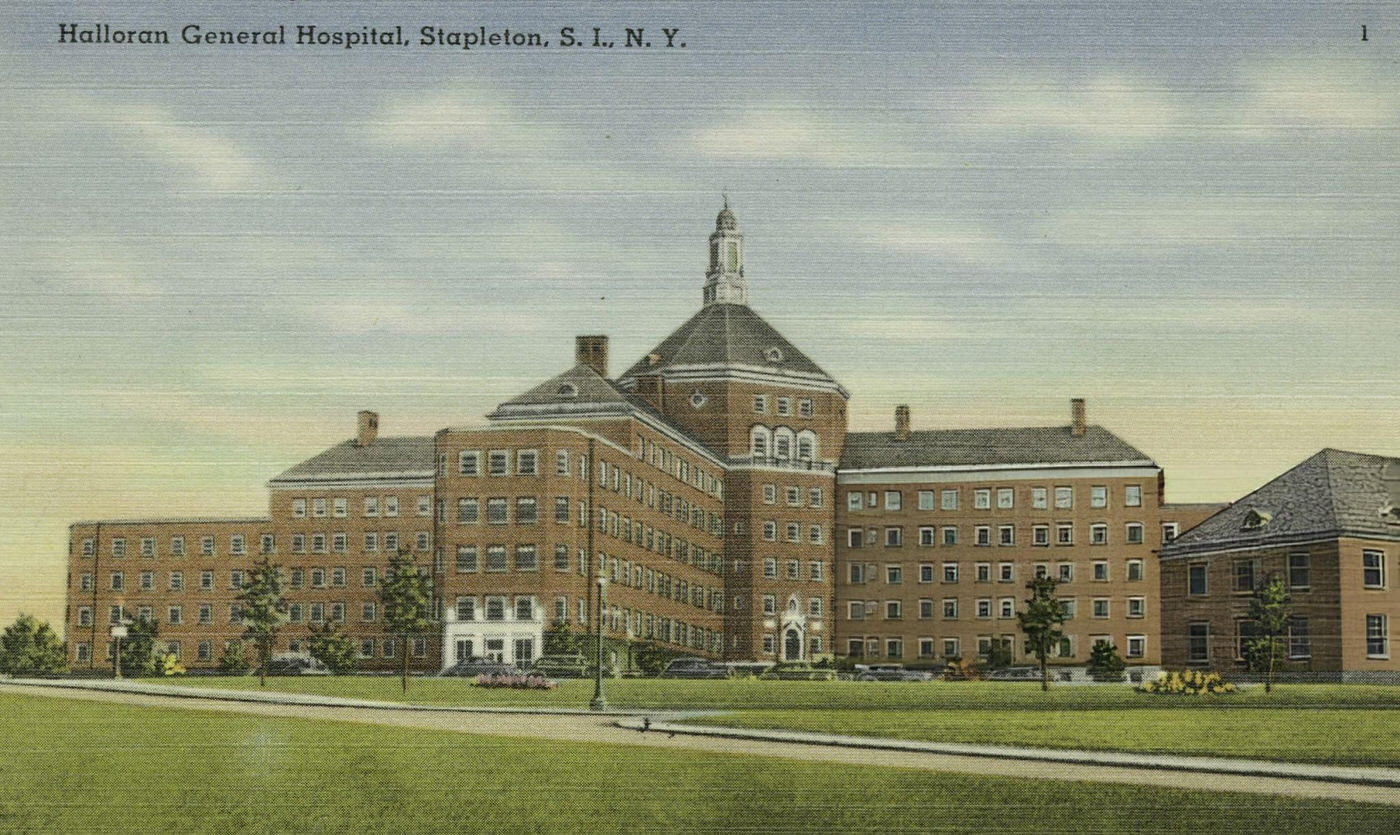

In the early decades of the 20th century, New York City hospitals were institutions undergoing a profound transformation. They were caught between a past of basic custodial care and a future of scientific medicine. For the average New Yorker, entering a hospital was often a last resort, a step taken only in cases of serious injury or severe illness. The city’s hospitals were a mix of massive public institutions, charitable voluntary hospitals, and specialized facilities for specific ailments.

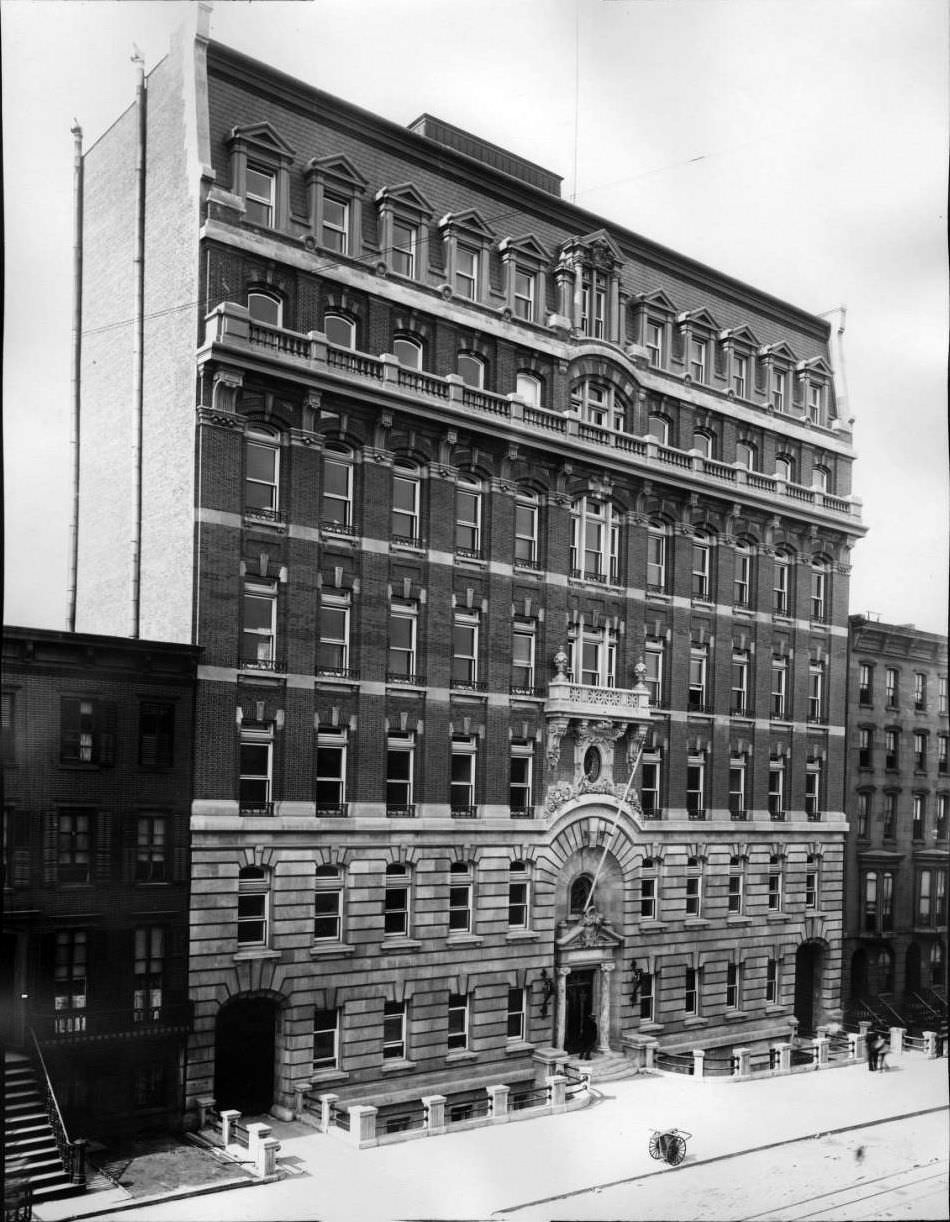

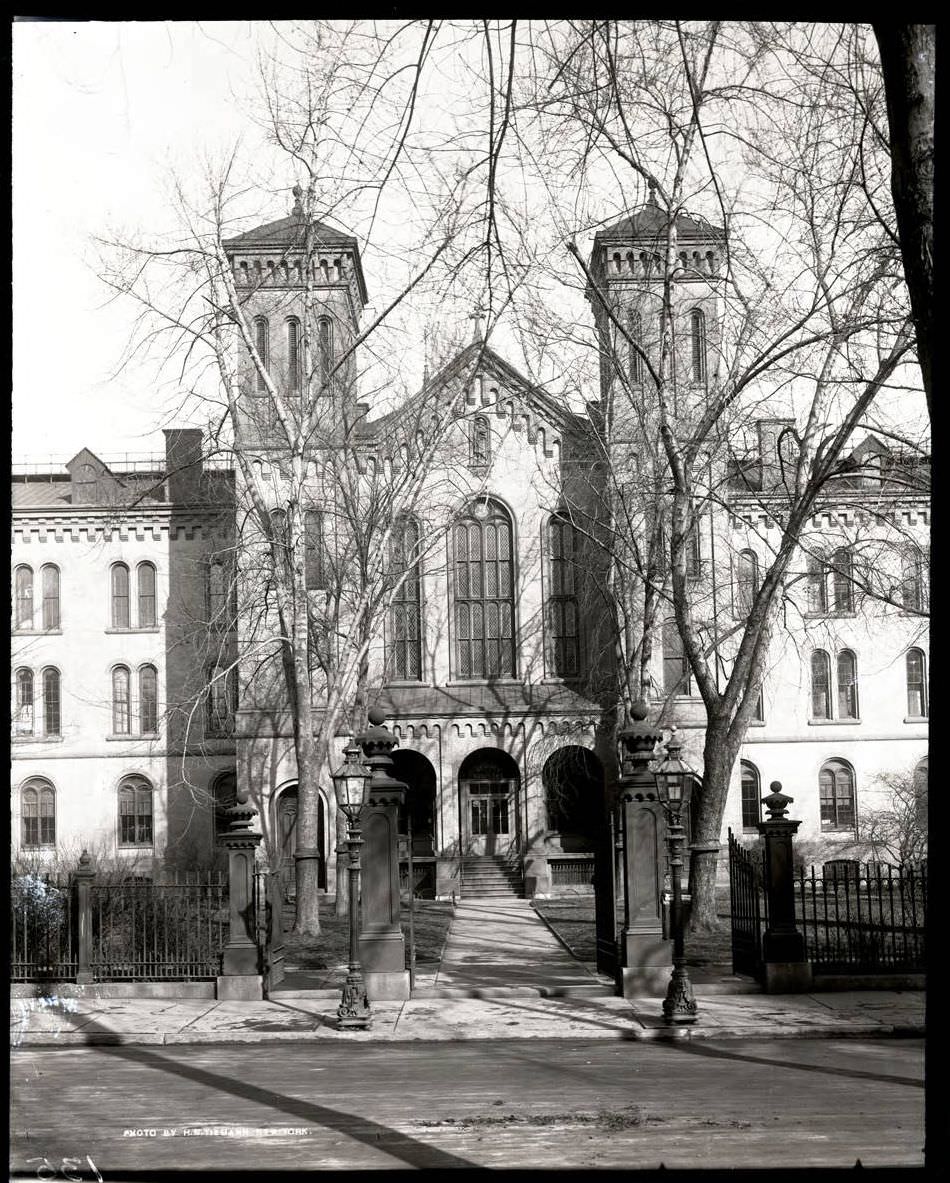

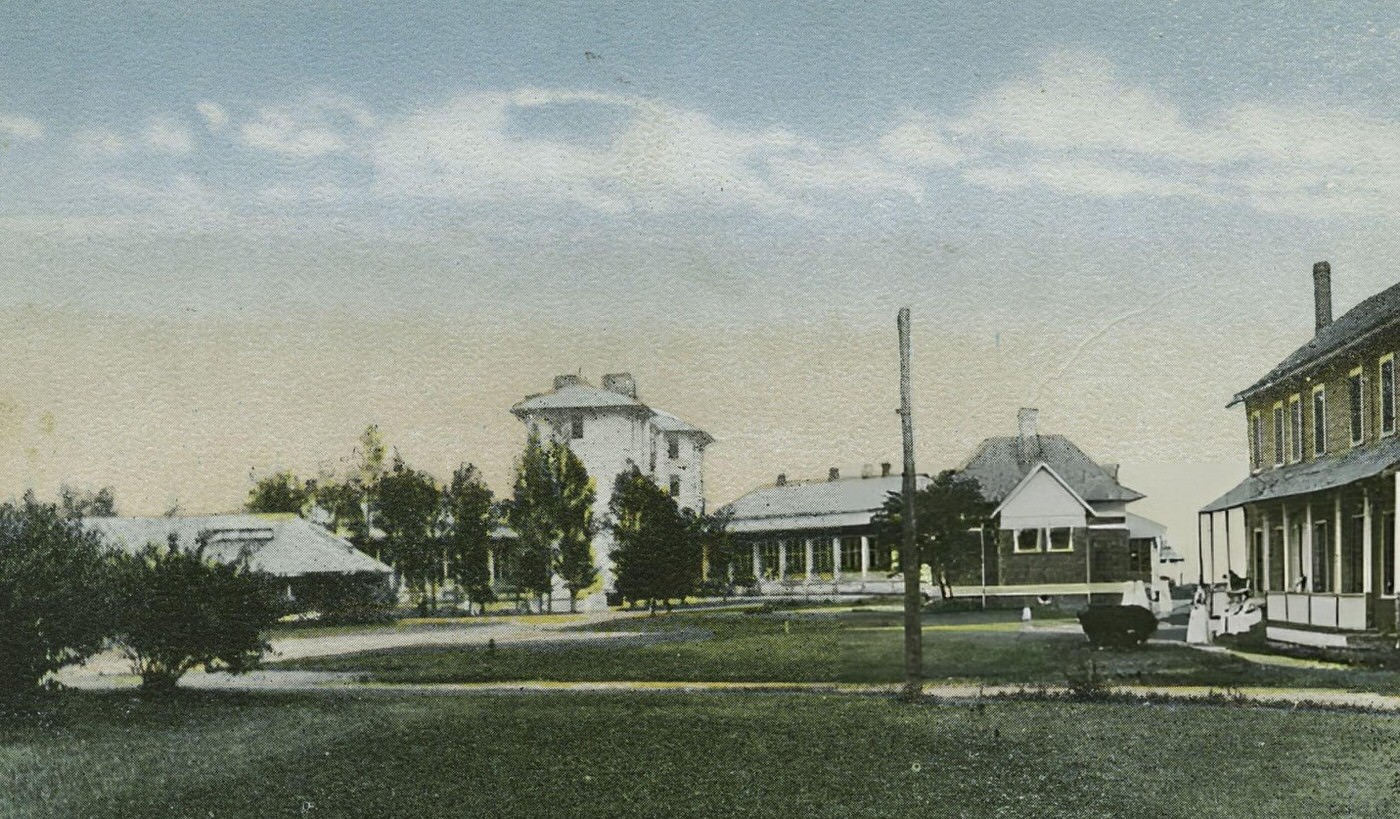

The most famous of the public hospitals was Bellevue, a sprawling campus on the East River that served as the primary destination for the city’s poor and for emergency cases. Its horse-drawn, and later motorized, ambulances were a common sight on city streets. Voluntary hospitals were often founded by specific religious or ethnic communities. Mount Sinai Hospital, for example, was established by the city’s Jewish community, while St. Luke’s and Roosevelt hospitals had Episcopalian and Presbyterian roots. These institutions were funded by wealthy philanthropists and catered to the city’s working and middle classes.

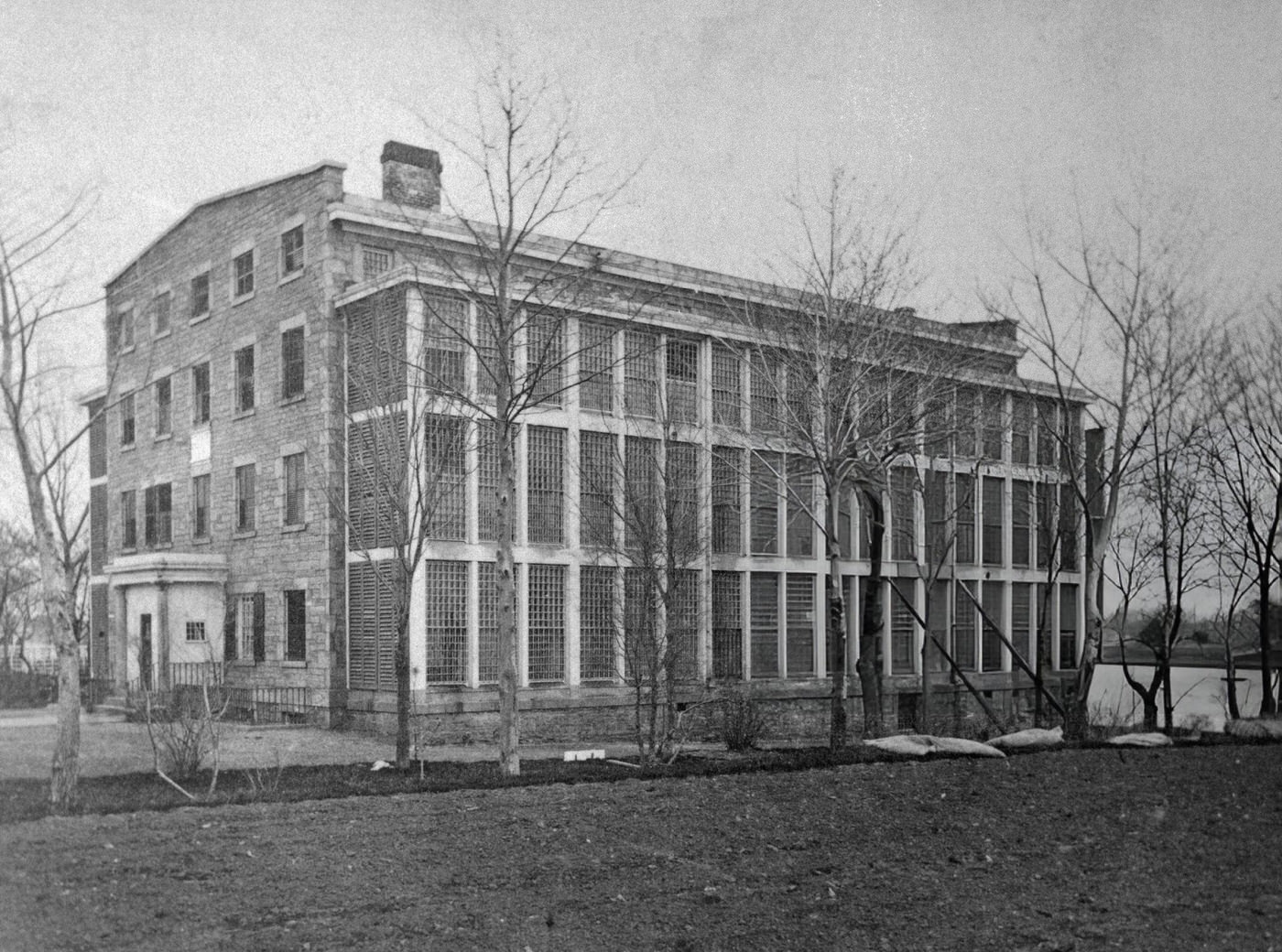

Inside the majority of these hospitals, the primary feature was the open ward. Wards were enormous, long rooms lined with dozens of metal-framed beds, often spaced only a few feet apart. A single large ward could hold 30, 40, or even more patients with various illnesses. Nurses, now increasingly professional and trained in specific hospital schools, moved efficiently through these spaces, monitoring patients, changing linens, and administering medications under the direction of a small staff of doctors. The atmosphere was one of disciplined routine, with set times for meals, doctors’ rounds, and visitors.

Read more

This was a critical era for medical advancement. The principles of antiseptic and aseptic surgery were becoming standard practice. Operating rooms were now frequently white-tiled spaces where surgeons and nurses wore gowns and masks to prevent infection. The discovery of the X-ray in 1895 meant that larger hospitals in the early 1900s were installing their first primitive X-ray machines, allowing doctors to see inside the human body without surgery for the first time. Professional laboratories were also becoming central to hospital work, enabling the diagnosis of diseases like diphtheria, typhoid, and tuberculosis through scientific analysis.

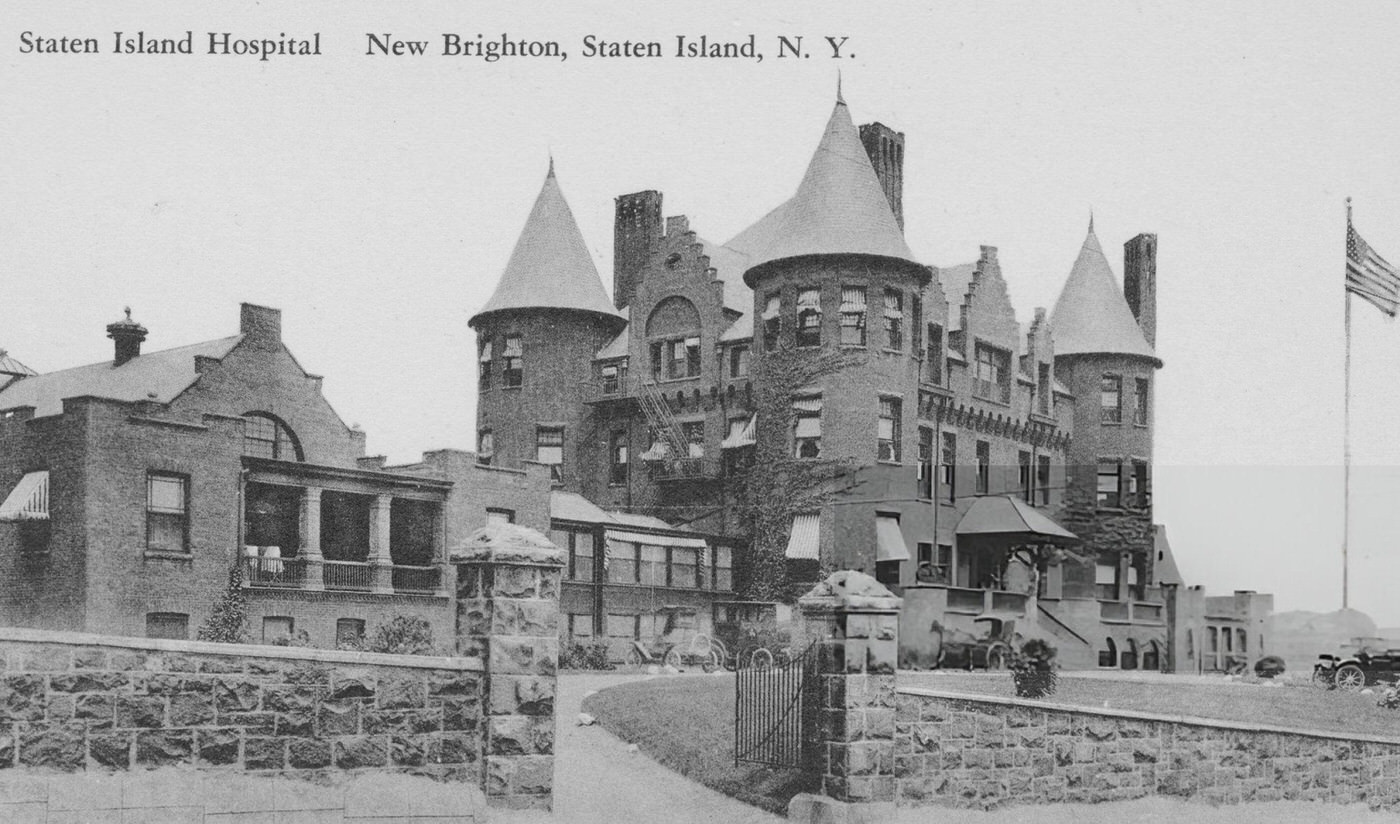

Specialized hospitals handled specific public health crises. The Willard Parker Hospital was dedicated solely to treating patients with contagious diseases, especially scarlet fever and diphtheria, placing them in isolation to prevent wider outbreaks in the crowded city. The New York Lying-In Hospital was one of the first institutions dedicated specifically to childbirth, aiming to provide a safer environment for mothers than a home birth in a crowded tenement. These hospitals were on the front lines of the city’s constant battle against injury and infectious disease.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings