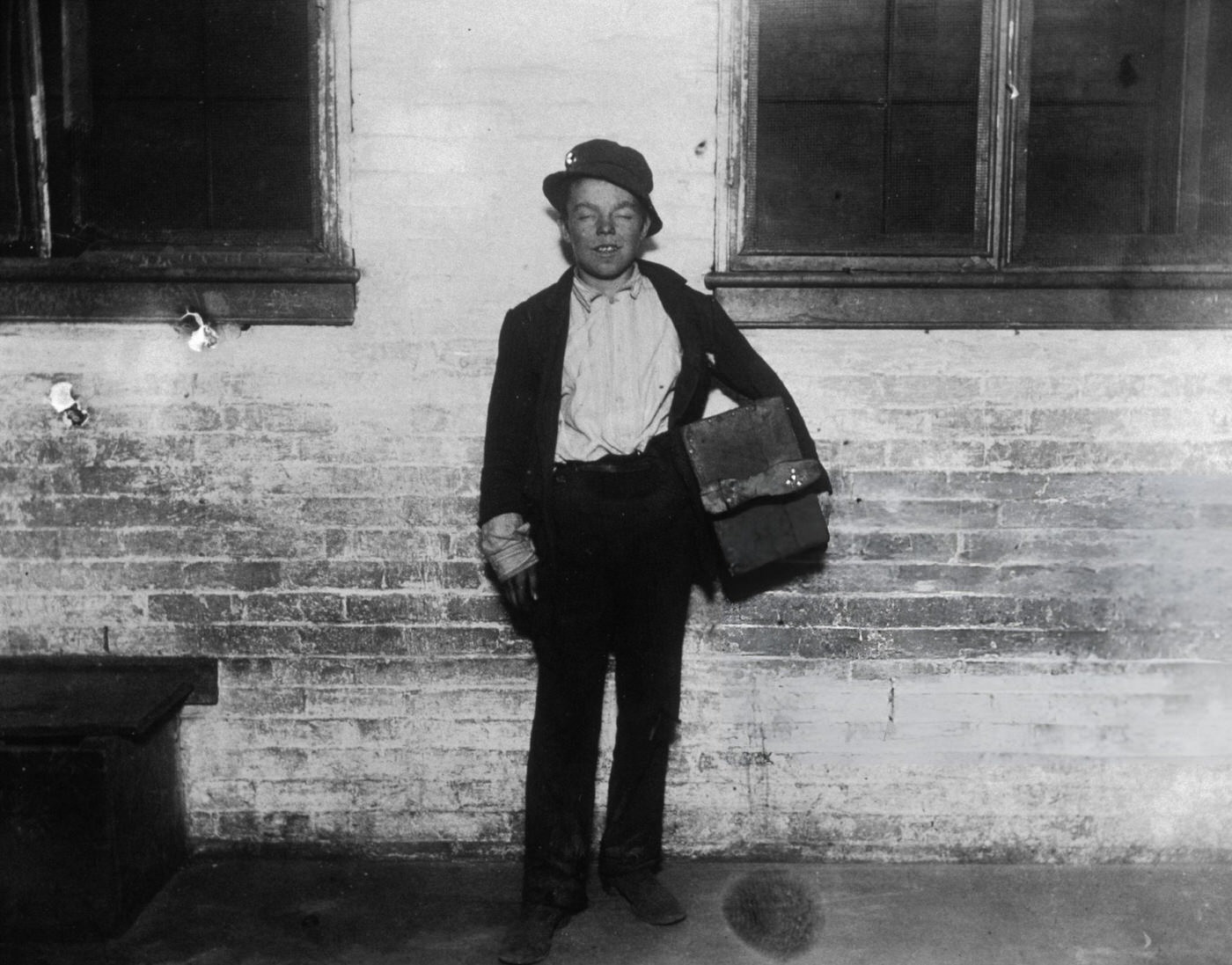

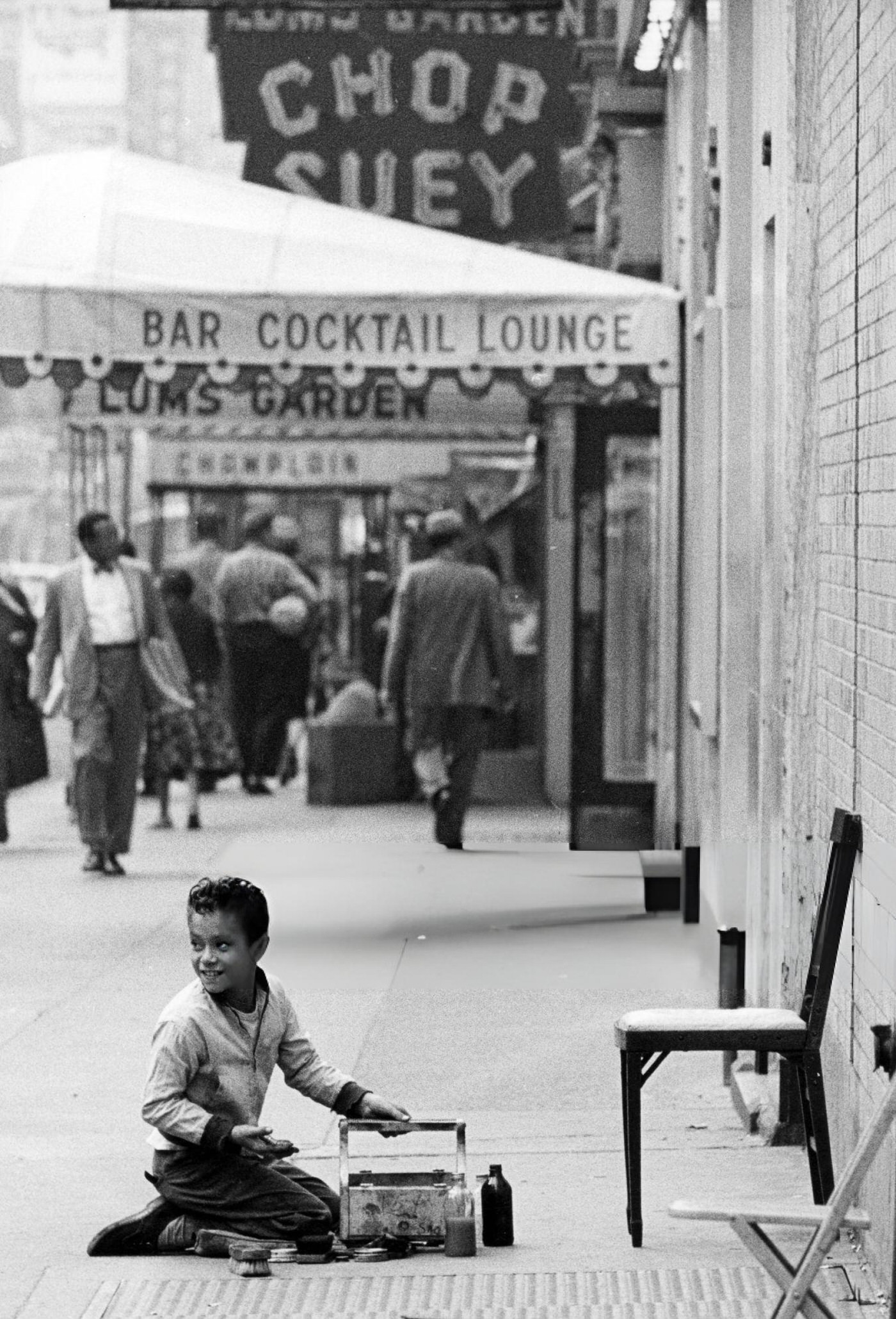

On the bustling streets of late 19th and early 20th century New York City, shoe shine kids were a constant presence. Often as young as six or seven, these boys, known as “bootblacks,” worked to earn a few crucial pennies for themselves and their families. They were a visible part of the city’s massive street-level economy.

The Tools of the Trade

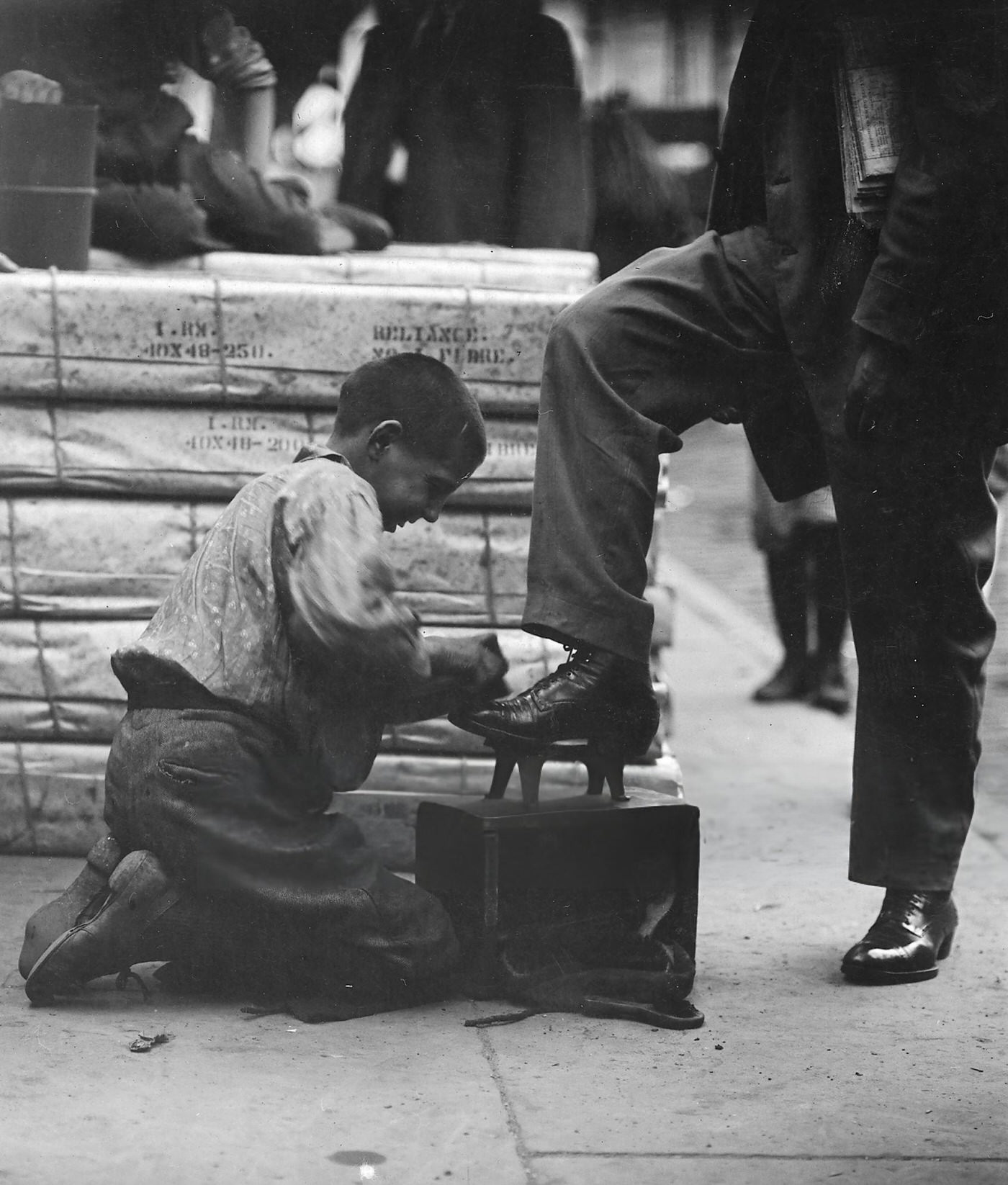

A bootblack’s entire business was contained in a single wooden box. This box, often homemade, served as a tool chest, a storage unit, and a stool for the customer. The top of the box was fitted with a metal footrest for the client’s shoe.

Inside, a boy kept his essential equipment: at least two brushes, one for applying the polish and another for buffing the shoe to a high gloss. He carried tins of polish, called “blacking,” and a collection of soft rags or scraps of flannel for the final shine. This simple, portable kit was his workstation and his livelihood.

The Battle for Customers

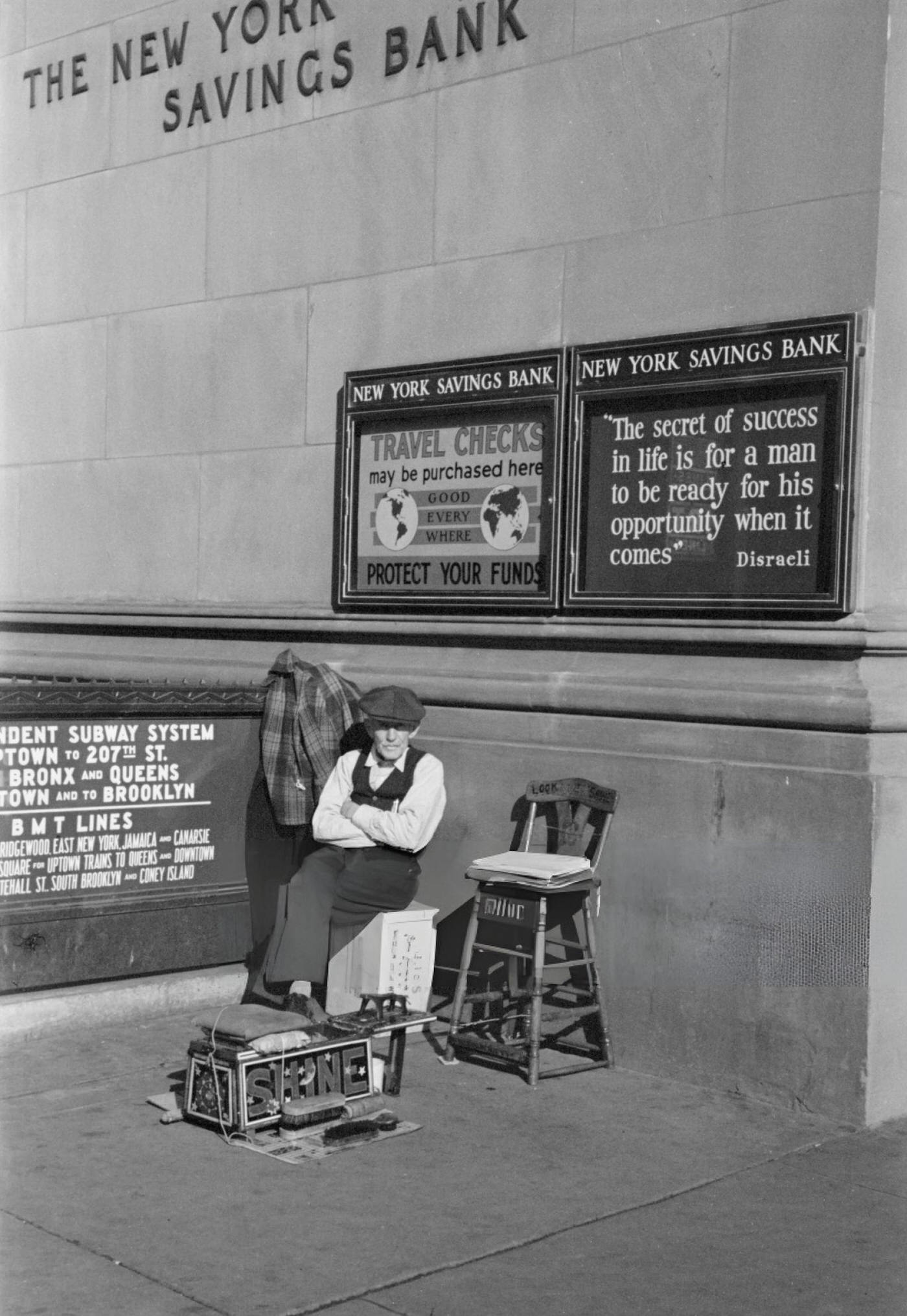

Shoe shine kids strategically positioned themselves in areas with heavy foot traffic. They were found near City Hall Park, along Wall Street, outside ferry terminals, and at the entrances to major hotels and theaters. These were the places where businessmen, clerks, and gentlemen in leather shoes were most likely to pass.

Read more

The competition was fierce. A boy had to be quick, loud, and persuasive to secure a customer before another did. Their call of “Shine ’em up, mister?” was a familiar sound on the city’s sidewalks. They vied for the best corners and developed rivalries and territories to protect their business.

Pennies for Survival

The majority of these boys were the children of recent immigrants from Italy, Ireland, and Eastern Europe, living in crowded tenements. This was not a hobby; it was a job born of necessity. A single shine cost between three and five cents. The money earned each day contributed directly to food and rent for their families.

Many bootblacks were independent entrepreneurs, buying their own supplies and keeping their profits. Others, particularly younger Italian boys, worked for a “padrone.” This system involved an adult who would provide the kits and supplies in exchange for a large portion of the boy’s daily earnings.

An Unofficial Network

Working long hours on a single corner made these boys experts on the neighborhood’s daily rhythms. They knew the schedules of police officers, the habits of local businessmen, and the general gossip of the street. They witnessed everything from business deals to street fights, making them an integral part of the flow of information in their corner of the city.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings