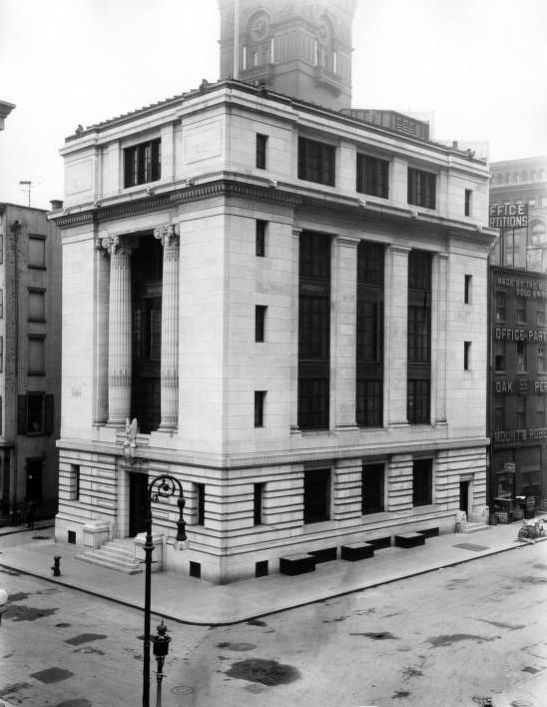

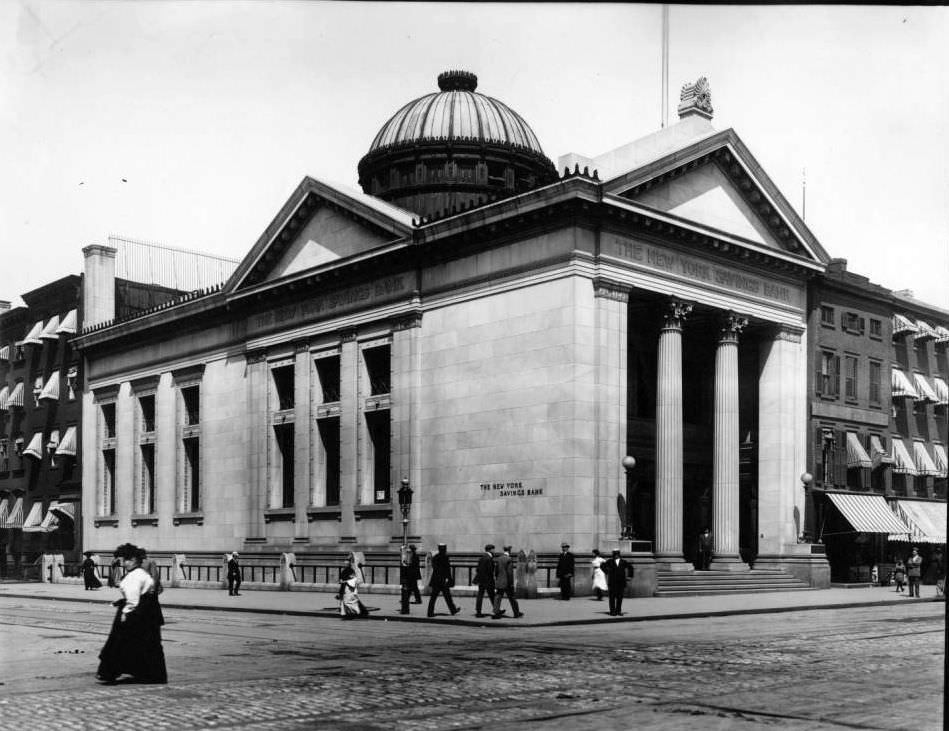

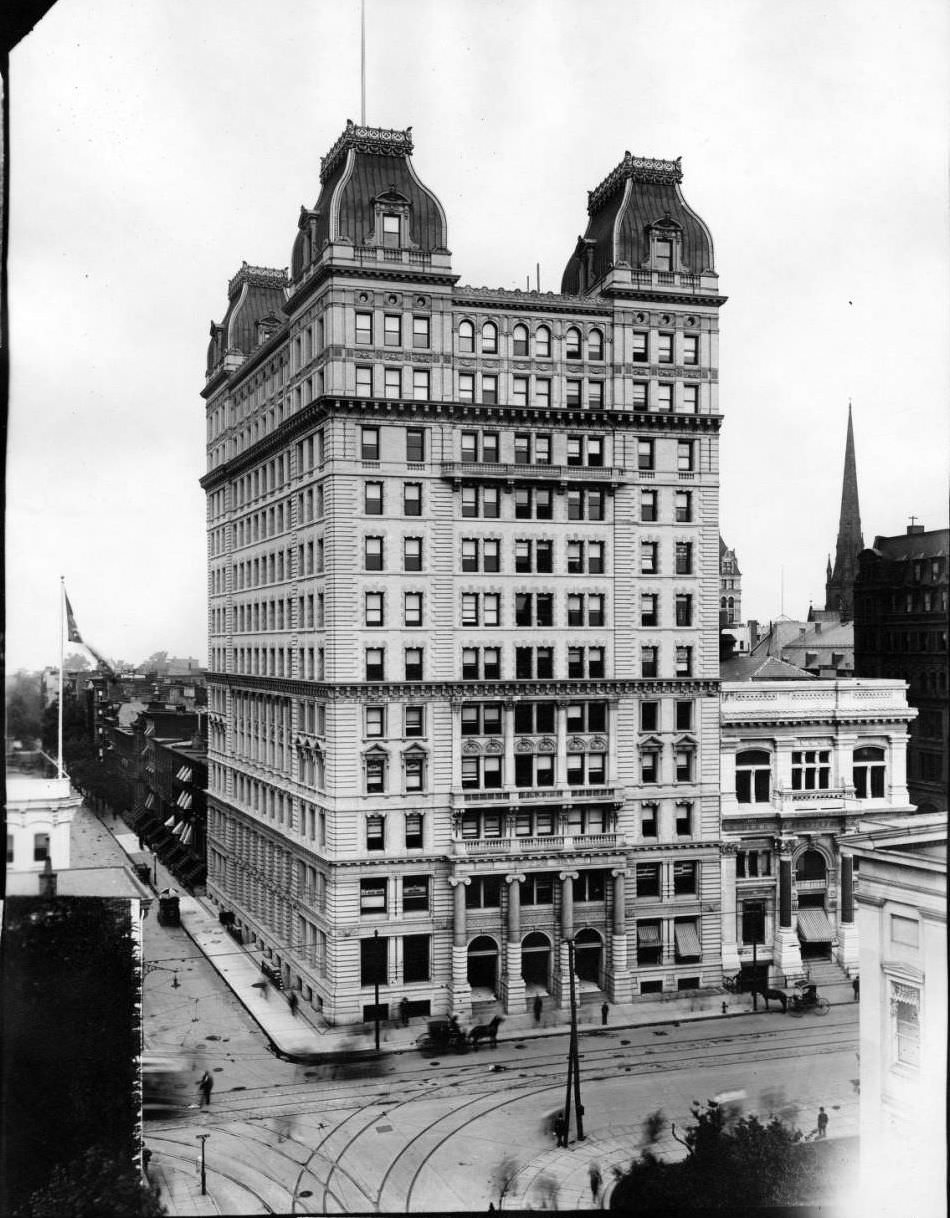

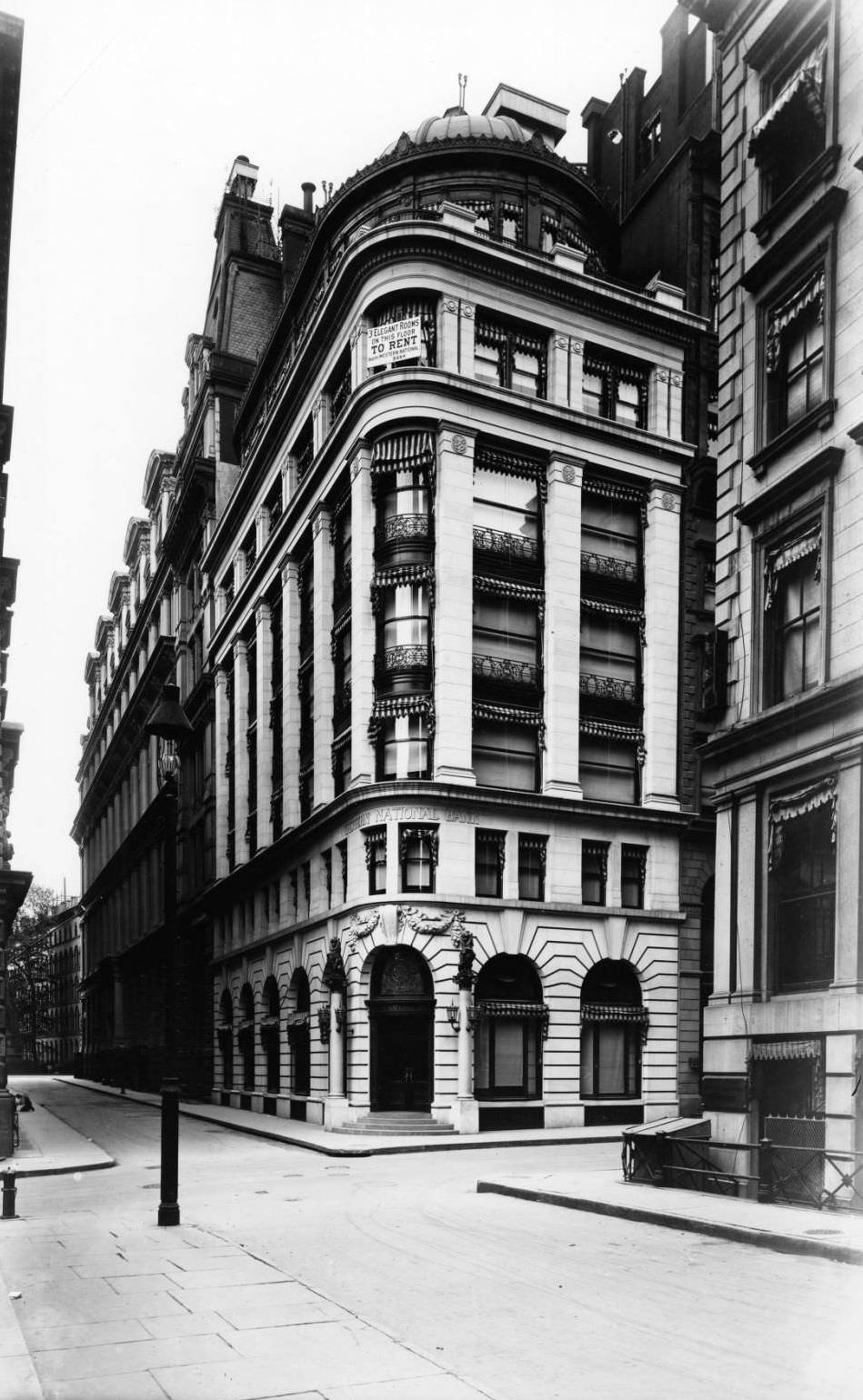

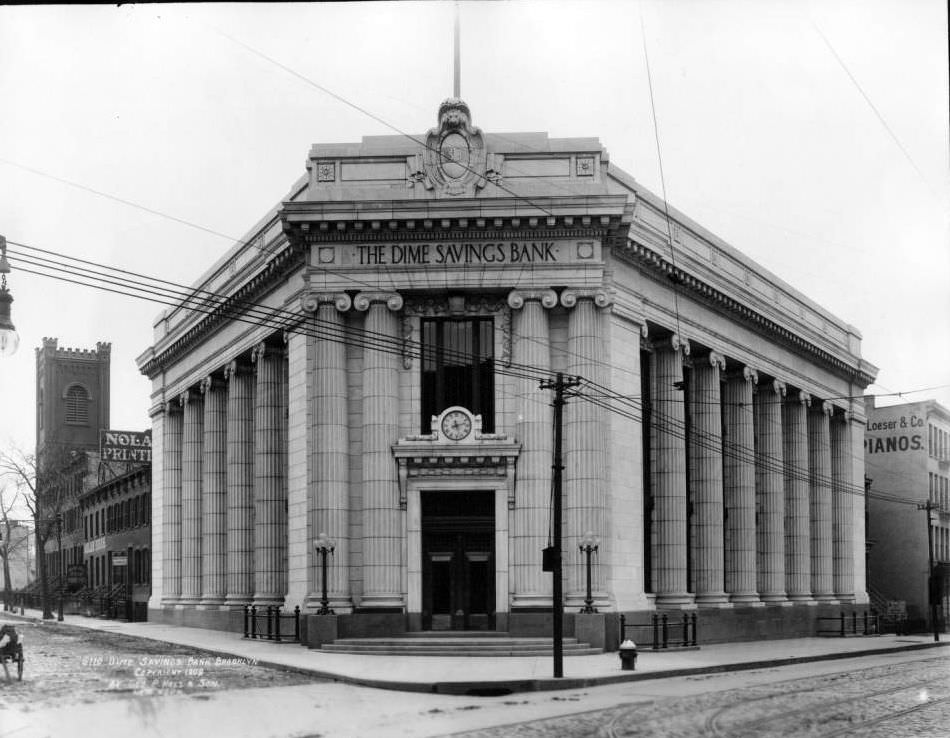

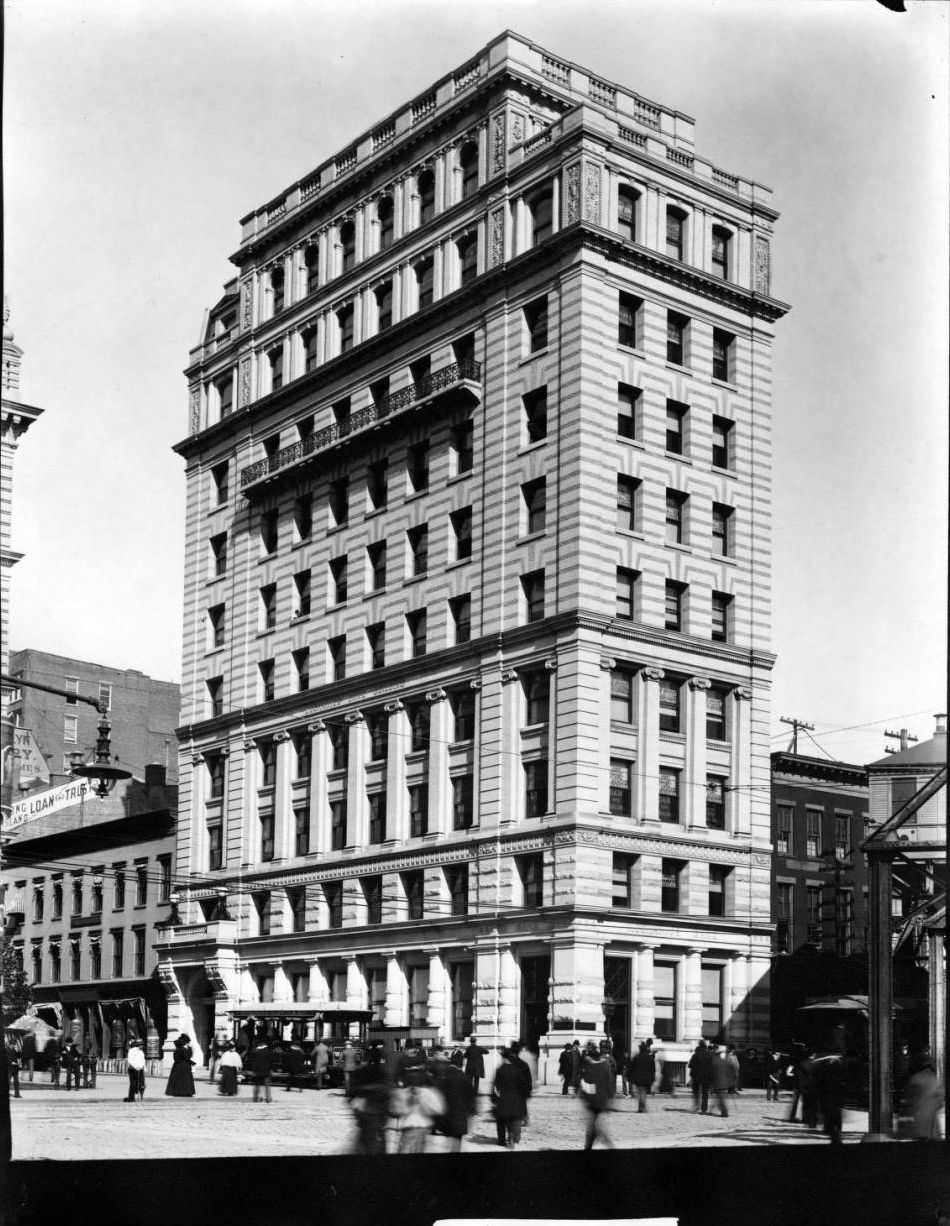

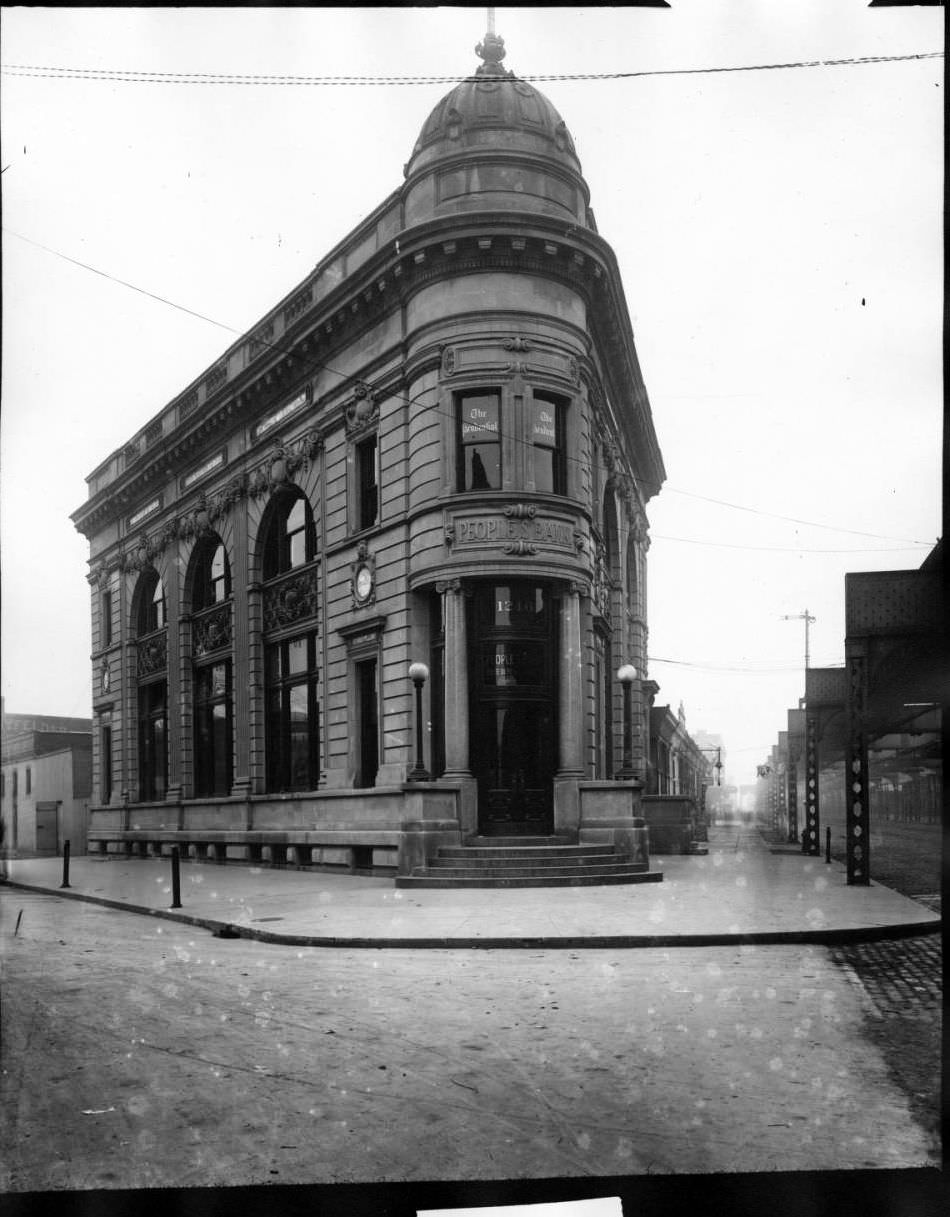

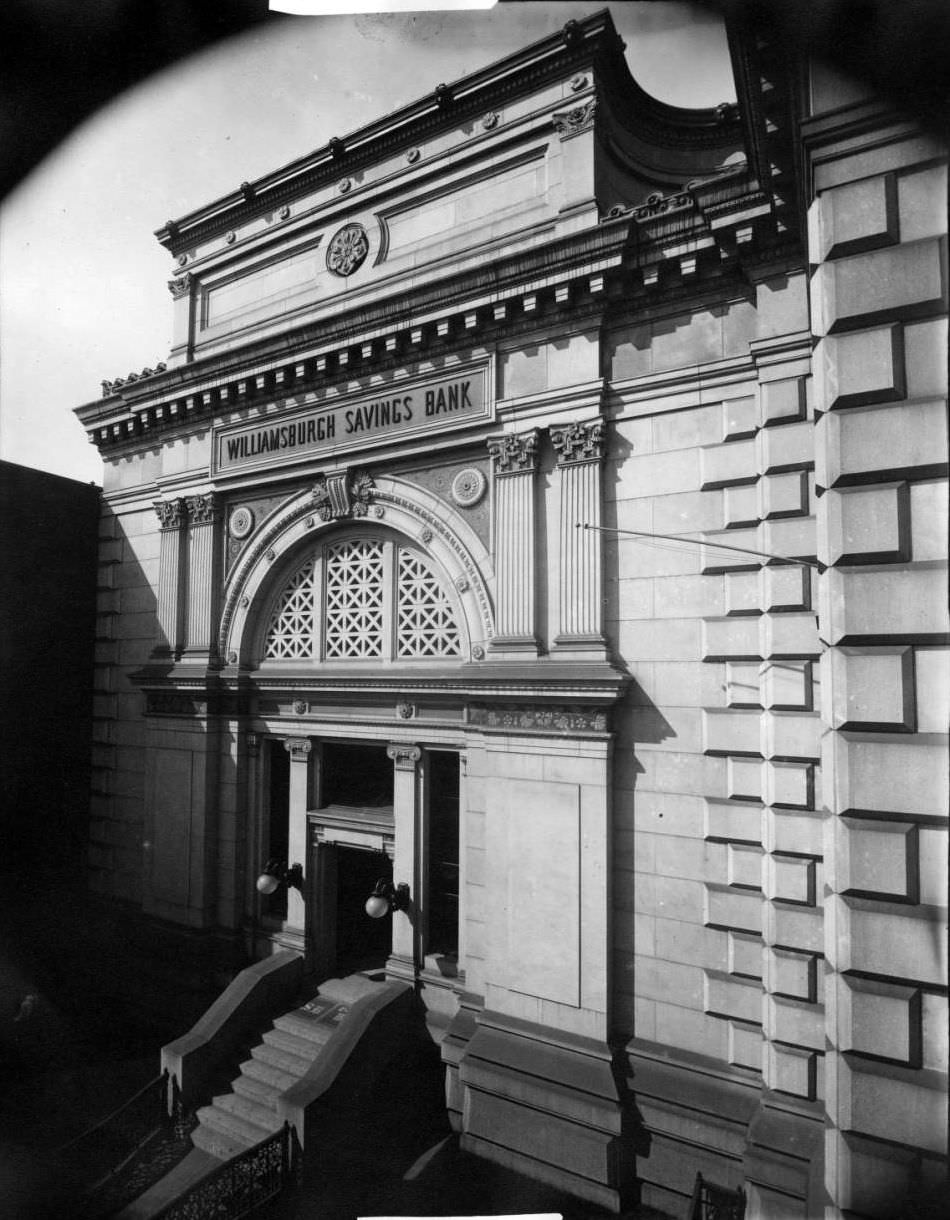

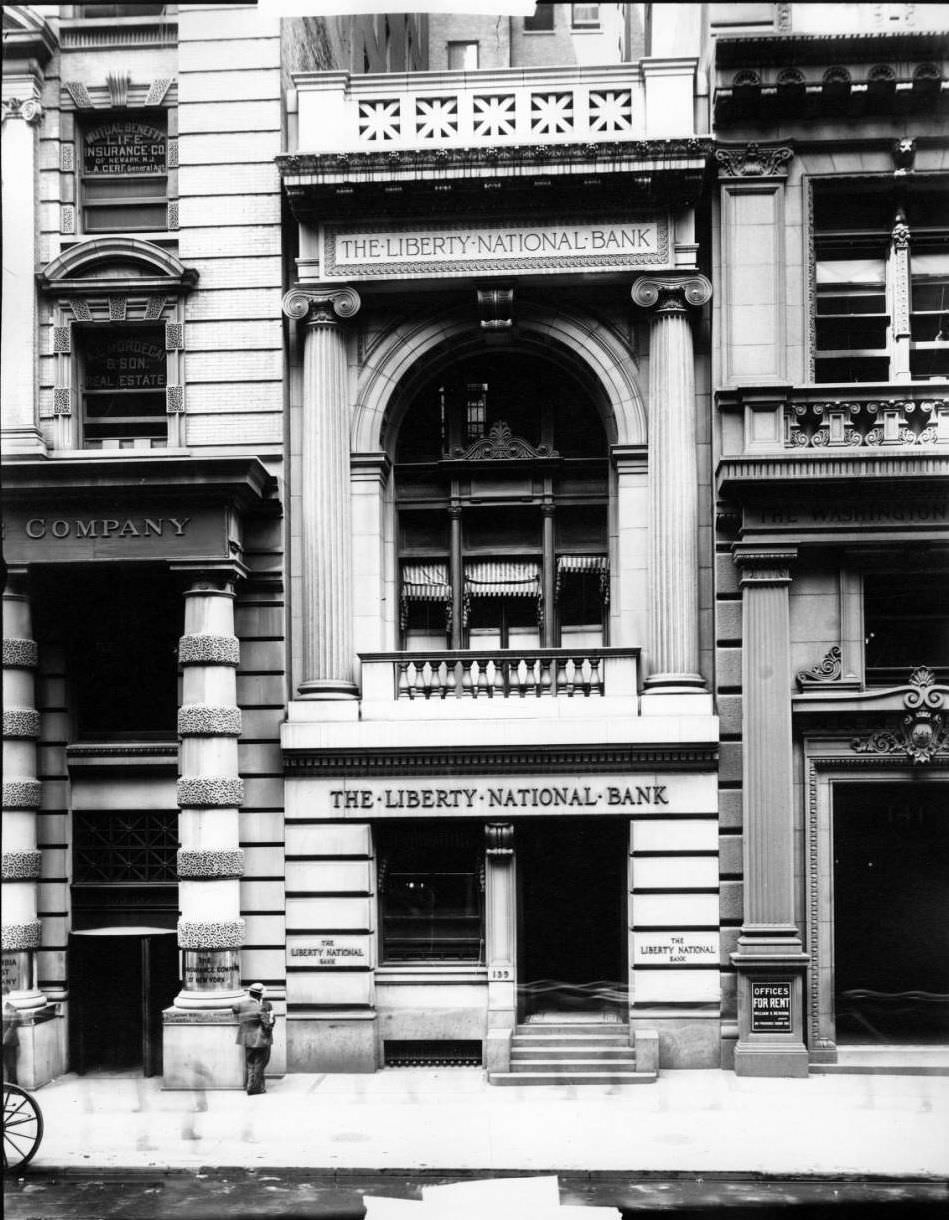

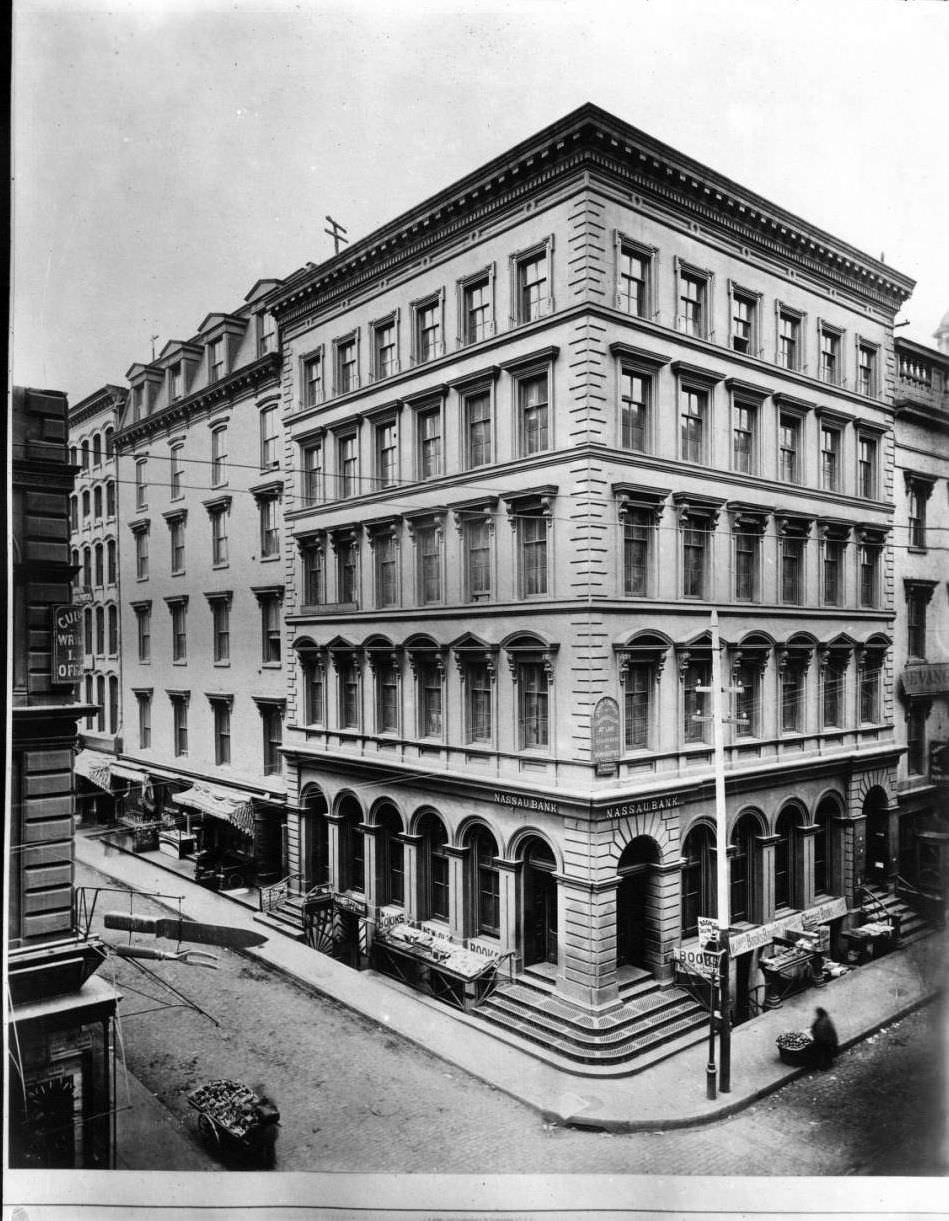

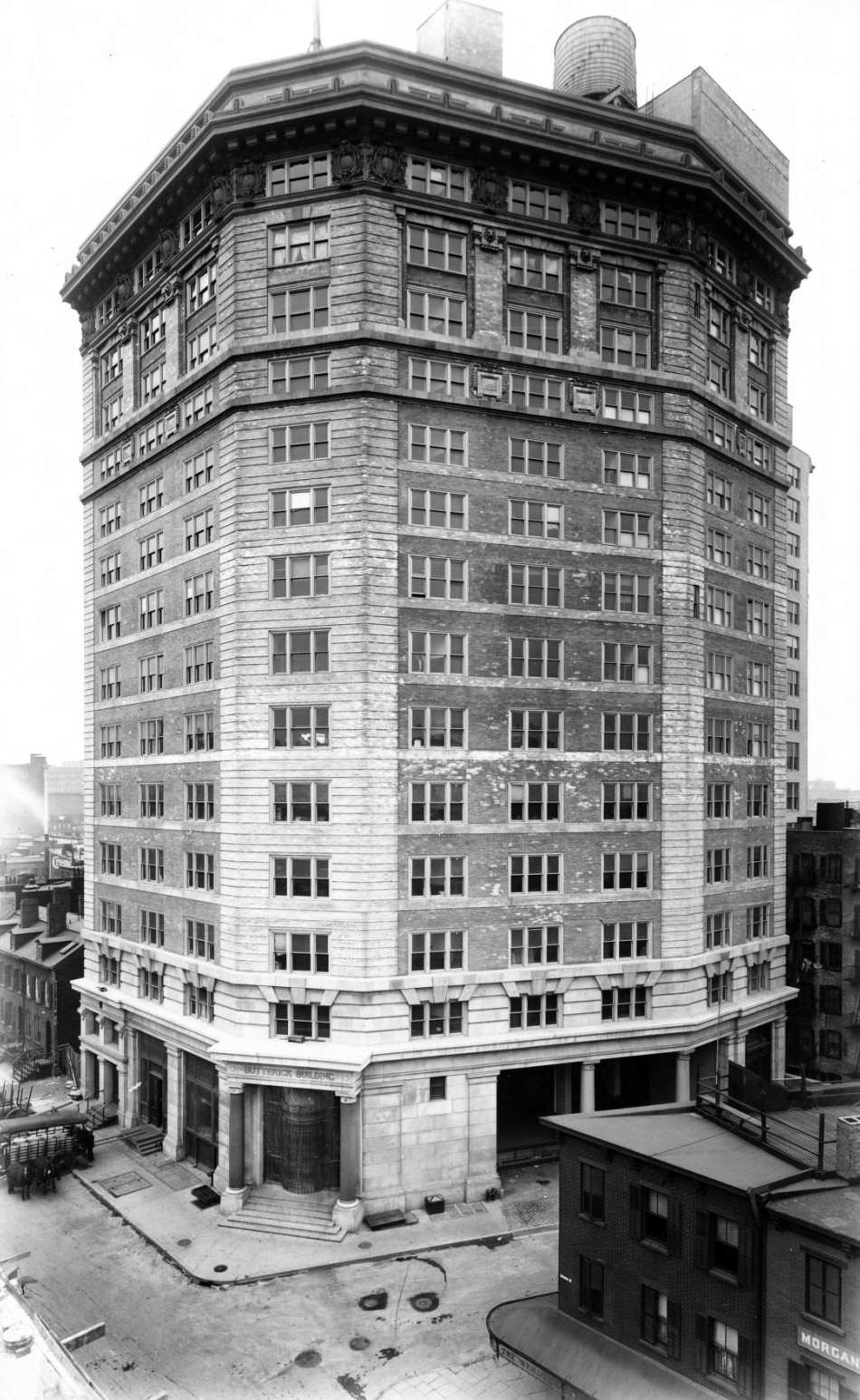

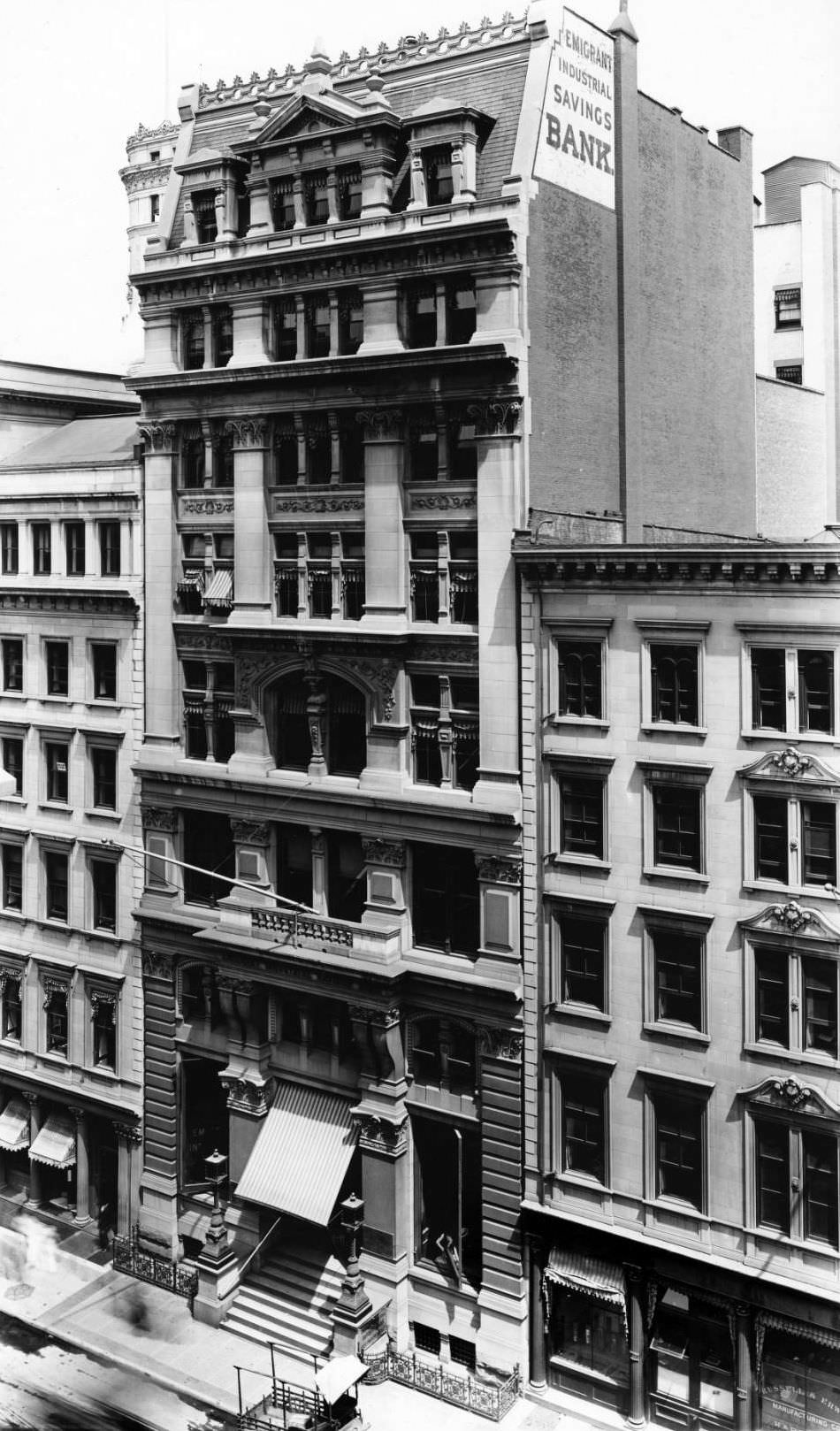

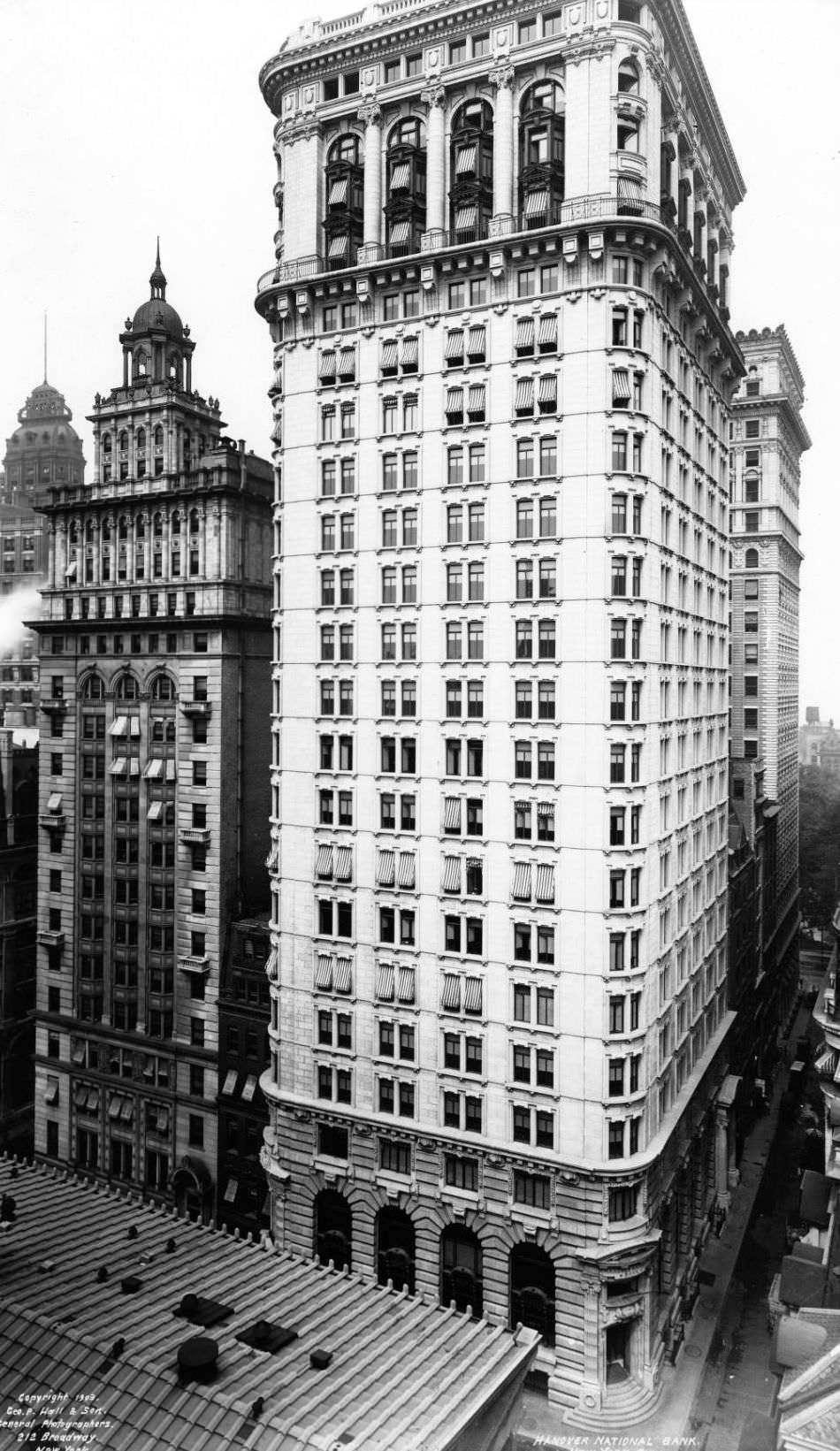

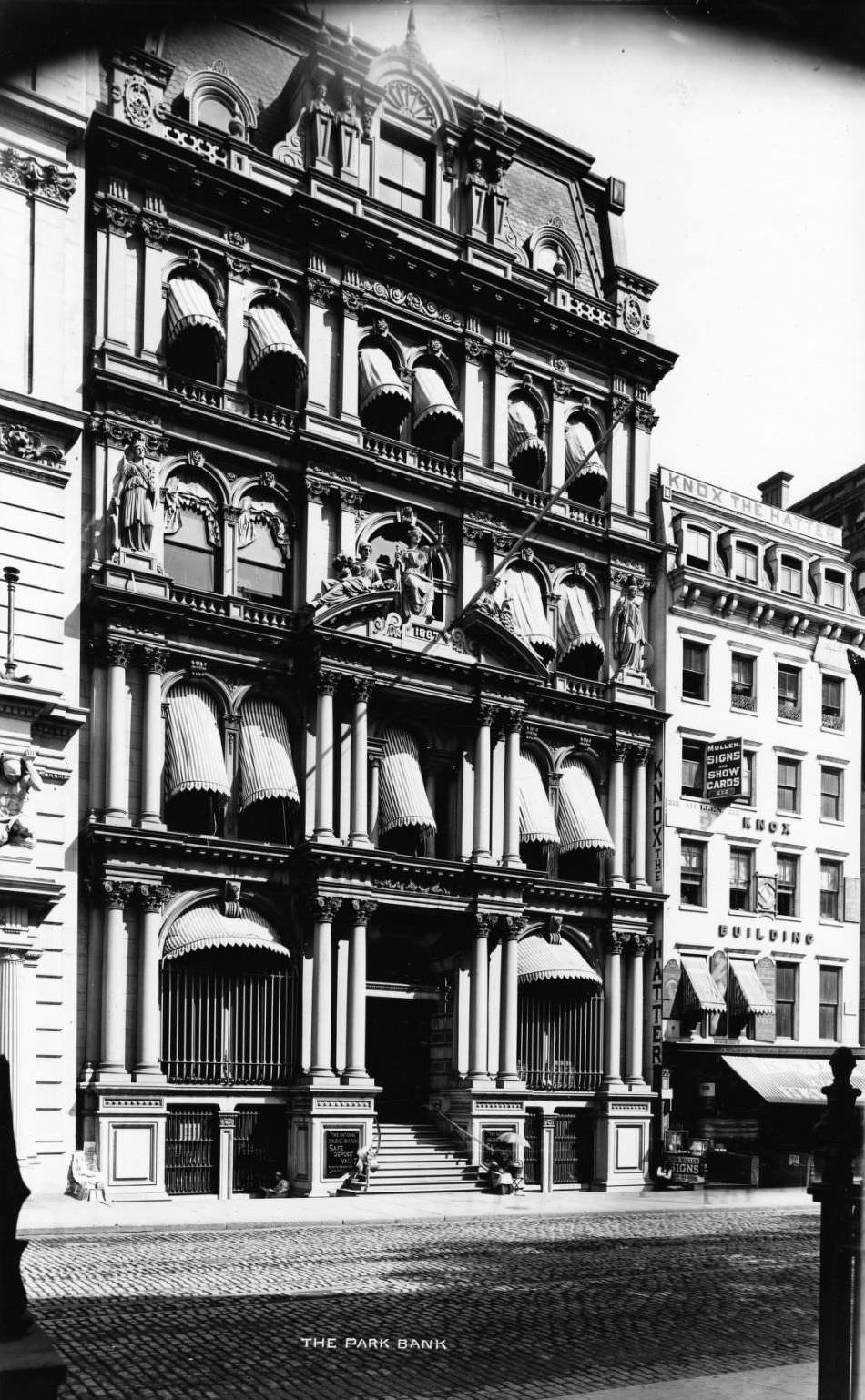

In the early decades of the 20th century, New York City’s banks were built to look like ancient temples. Clustered in the narrow streets of Lower Manhattan, these institutions were designed to project an image of immense power and permanence. The architecture was a direct message to the public and the world: the money inside was safe, protected by thick stone walls, massive bronze doors, and a forest of marble columns.

The area around Wall Street was the undisputed center of American finance. Here stood the headquarters of the most powerful financial firms. The National City Bank of New York, a forerunner of Citibank, operated out of a massive building at 55 Wall Street that had formerly been the Merchant’s Exchange. The First National Bank, another giant, had its own imposing headquarters. The most famous address was 23 Wall Street, the headquarters of J.P. Morgan & Co. The Morgan building was a low, austere, classical structure of solid marble that stood directly across from the New York Stock Exchange. It had no large signs, only the small inscription of the company name, a symbol of its immense, understated power.

Inside these banking halls, the atmosphere was one of quiet reverence and serious business. Floors were made of polished marble or intricate tile mosaics. Soaring ceilings, often with decorative plasterwork or painted murals, rose high above the main floor. Sunlight streamed through tall, arched windows. Customers did not approach an open counter but stood before ornate metal cages. Tellers, known as bank clerks, worked behind these brass or bronze grilles, handling transactions with a formal, professional demeanor. Every deposit and withdrawal was meticulously recorded by hand in a small, palm-sized passbook that served as the customer’s personal record of their account.

Read more

The city had different types of banks for different needs. The powerful commercial and investment banks like J.P. Morgan & Co. dealt with financing railroads, steel mills, and other massive industrial projects. They were the engines of the national economy. For ordinary New Yorkers, savings banks and trust companies were more common. Institutions like the Bowery Savings Bank and the Emigrant Savings Bank were built to serve the city’s working class and growing immigrant populations. They encouraged thrift by accepting small, regular deposits.

The financial system of this era was volatile. There was no Federal Reserve to act as a safety net. This reality was made clear during the Panic of 1907. A failed stock market speculation triggered a run on the city’s banks, with panicked depositors lining up for blocks to withdraw their money. As trust companies and smaller banks began to fail, the entire system neared collapse. In response, the financier J.P. Morgan personally took control. He gathered the presidents of the major banks in the library of his mansion and, through a combination of force of will and his own vast fortune, organized a private bailout to shore up the struggling institutions and restore order.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings