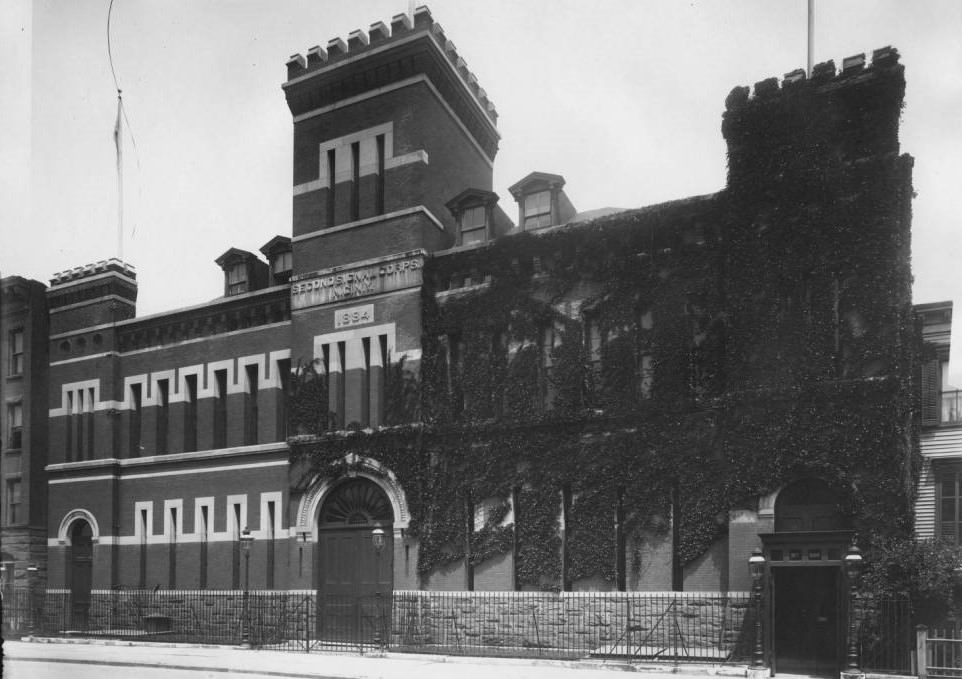

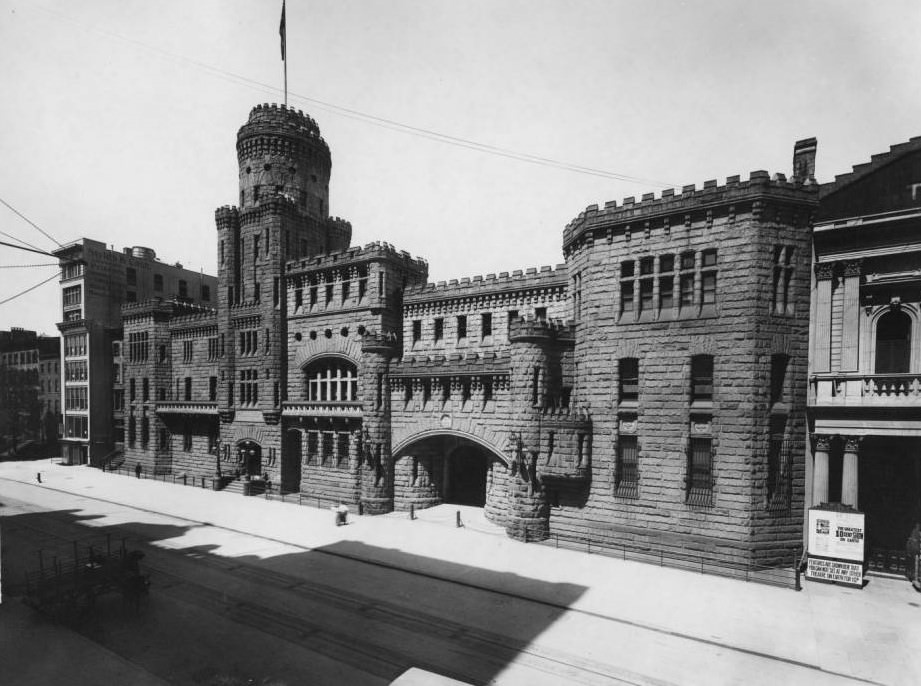

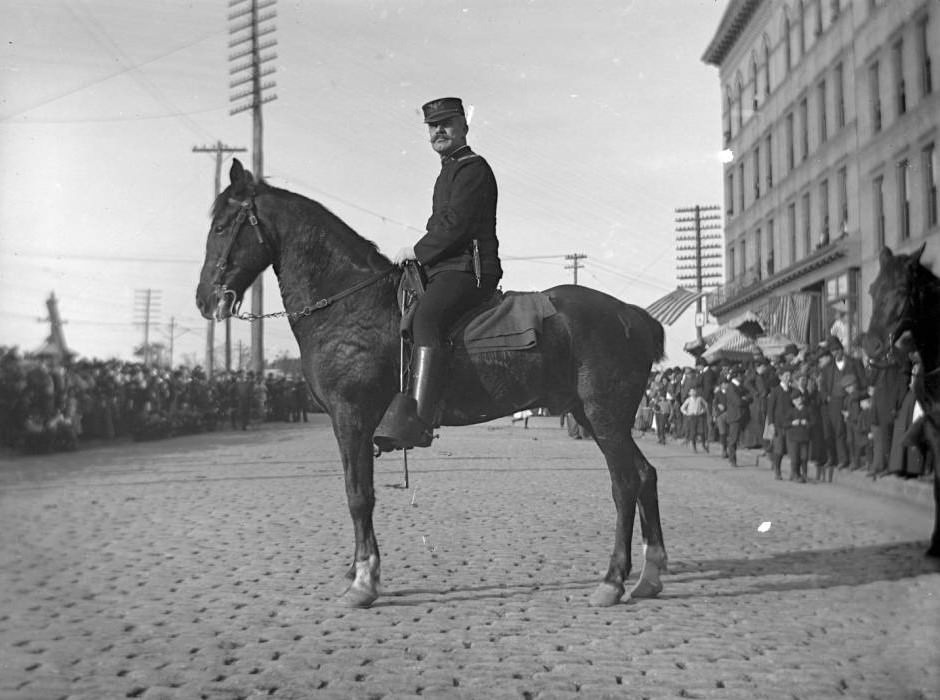

In the New York City of the early 1900s, massive, castle-like buildings stood on prominent avenues, looking more like medieval fortresses than modern structures. These were the city’s armories, the headquarters and training centers for the volunteer soldiers of the New York National Guard. Each armory was a symbol of civic power, a private clubhouse for its regiment, and a versatile public venue, all encased in thick walls of brick and stone.

These buildings were designed to be imposing. Their architecture featured crenelated towers, slit windows, and massive arched entrances, all intended to project an image of military strength and impenetrable security. They were built to be defensible, a lesson learned from the Draft Riots of the Civil War. Famous examples dotted the city. The Seventh Regiment Armory on Park Avenue was a socially exclusive institution, its membership filled with the sons of New York’s wealthiest families. The Ninth Regiment Armory on 14th Street and the Eighth Regiment Armory on Park Avenue, known for its gray stone facade, were other major Manhattan landmarks. Brooklyn also had its share of grand armories, including the large 23rd Regiment Armory on Bedford Avenue.

Read more

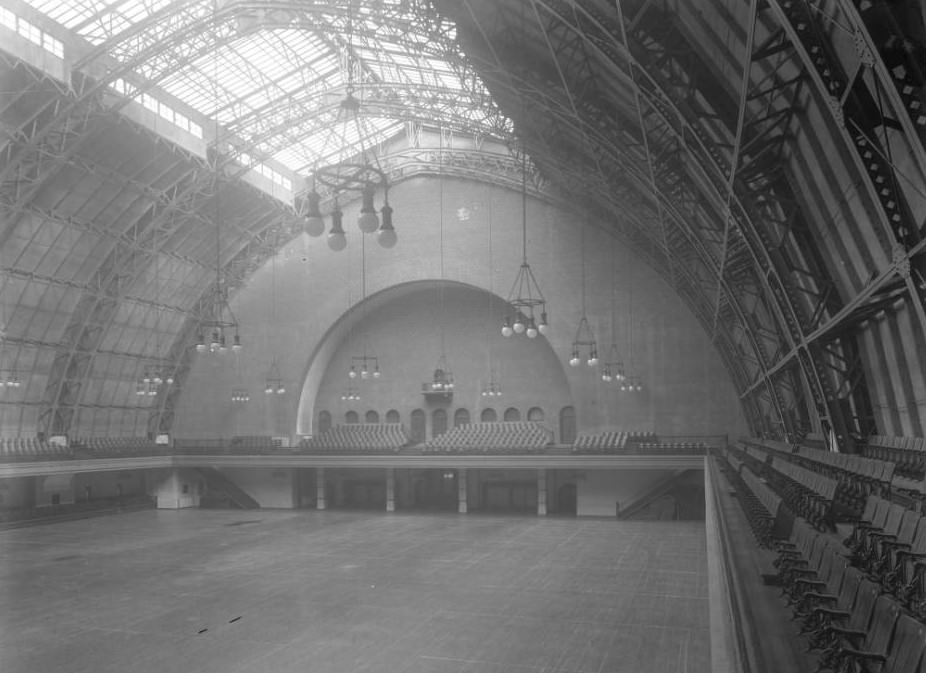

The heart of every armory was the vast, open drill hall. These enormous spaces, often measuring hundreds of feet in length, were engineering marvels of the time. Their arched roofs were supported by massive iron or steel trusses, creating an unobstructed interior large enough for a whole regiment to practice military formations and drills, safe from the weather. The floors were typically made of durable wood, strong enough to withstand the marching of a thousand men.

These drill halls also made the armories ideal venues for large-scale public events. When not being used for military training, their immense open spaces hosted track and field competitions, boxing matches, horse shows, and industrial exhibitions. The most famous event of the era took place in 1913 at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue. This was the International Exhibition of Modern Art, now known as the Armory Show. For the first time, a wide American audience was exposed to the shocking new works of European artists like Marcel Duchamp, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, making the armory the unlikely epicenter of a cultural revolution.

Beyond the public drill hall, the armories had a more private, club-like function. Each company within a regiment had its own dedicated room within the building. These company rooms were often lavishly decorated, funded by the members themselves. They featured wood-paneled walls, ornate furniture, libraries, and trophy cases displaying the regiment’s honors. For the guardsmen, the armory was not just a place to train; it was a social club, a second home where they could foster camaraderie and preserve the unique identity of their regiment.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings