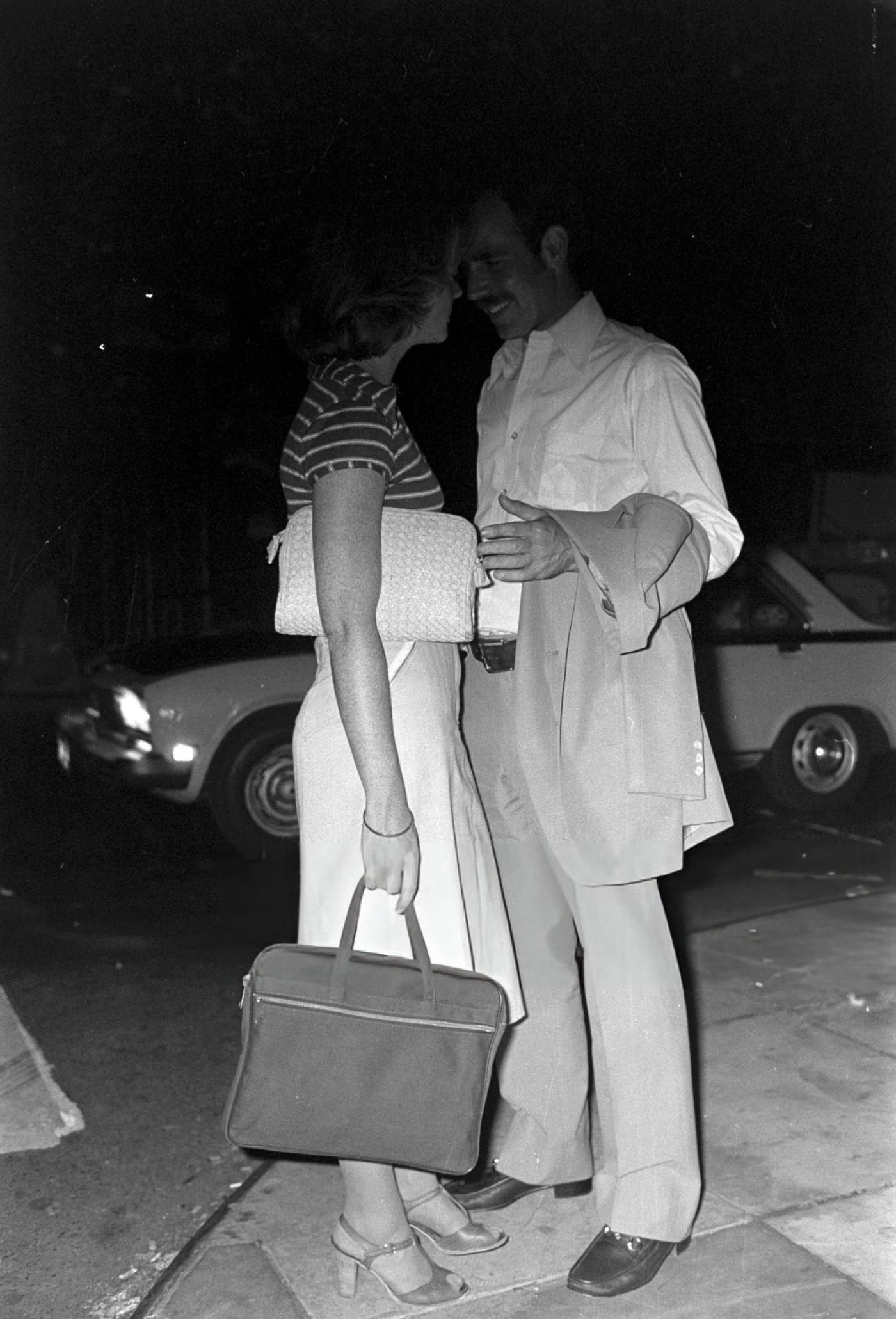

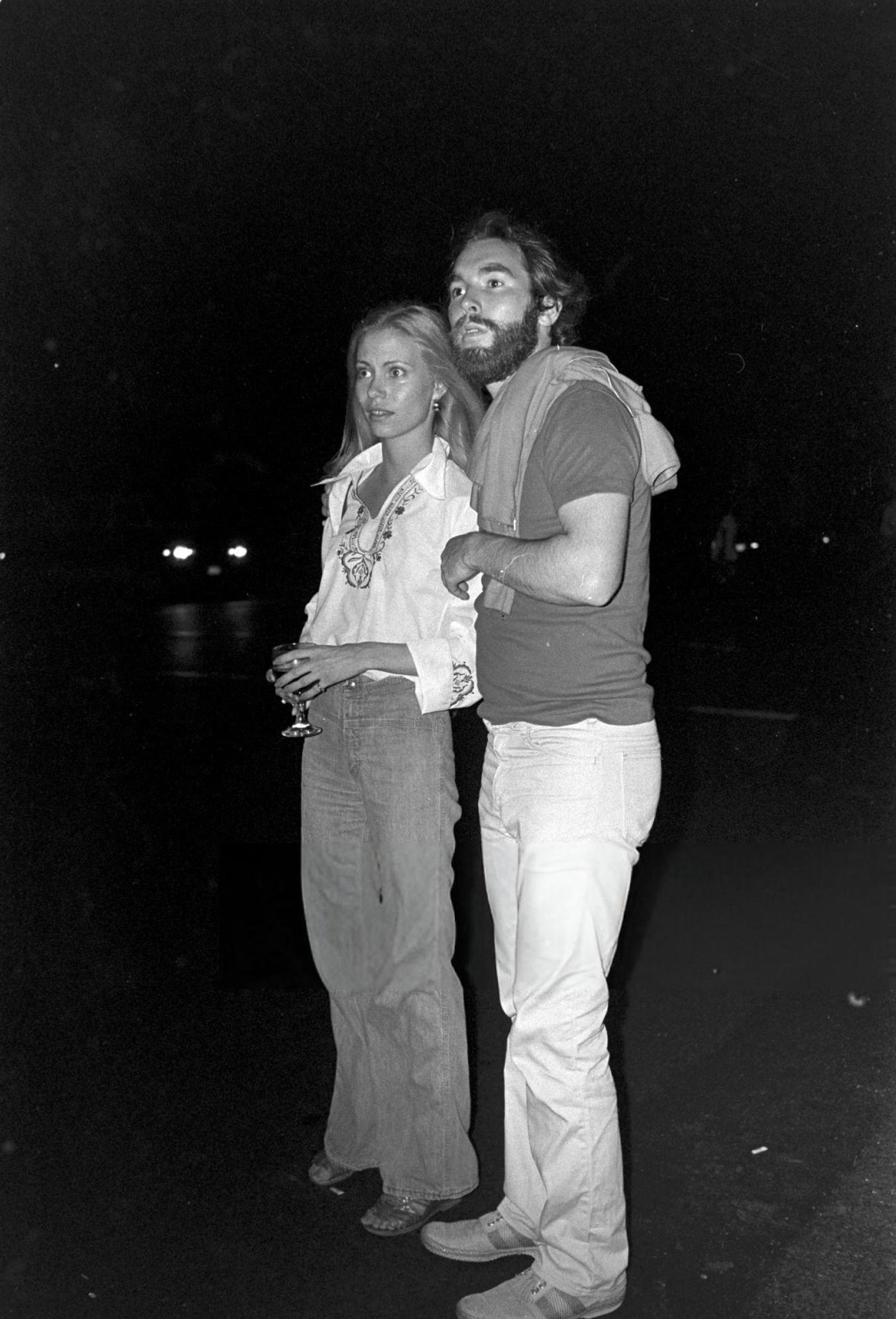

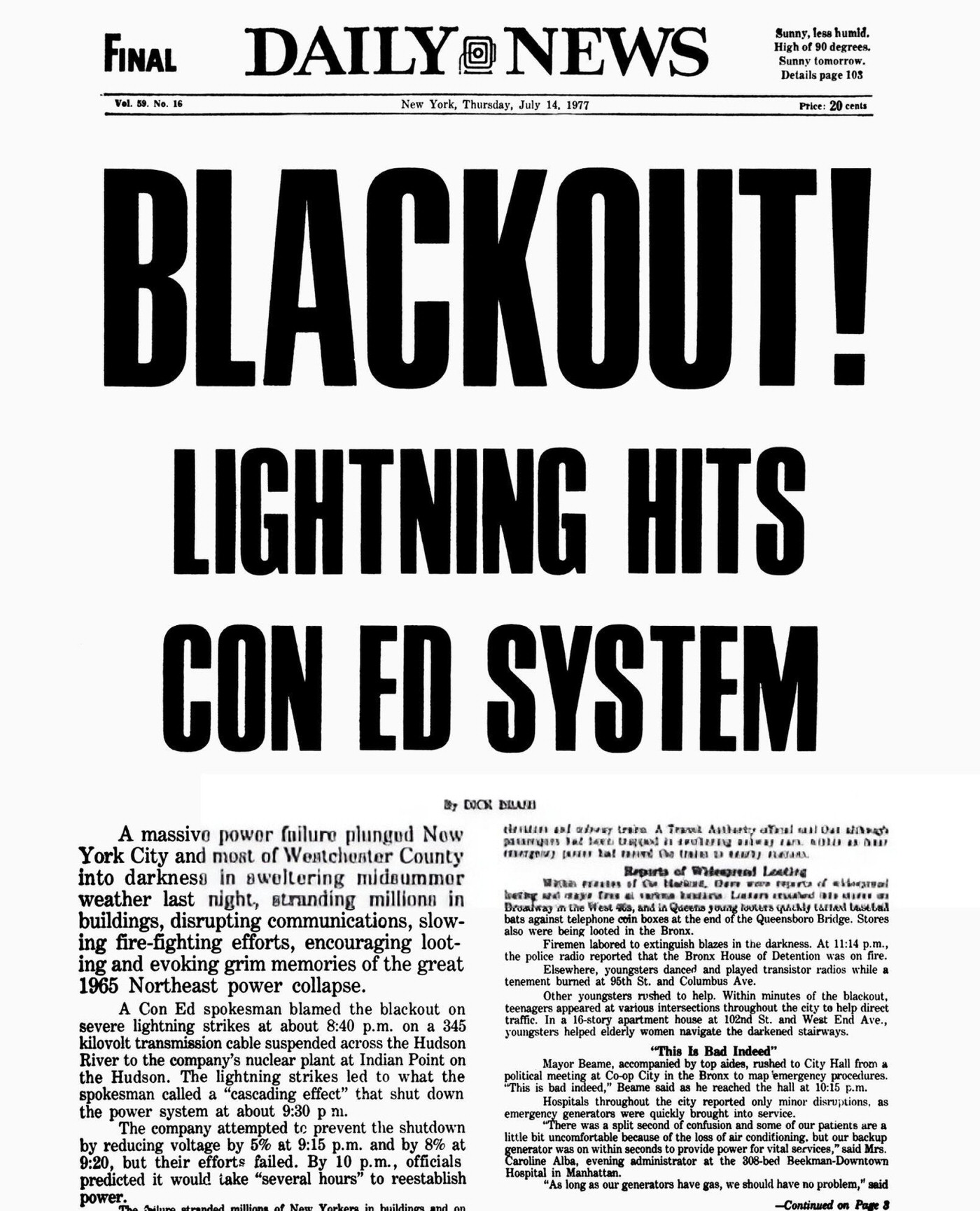

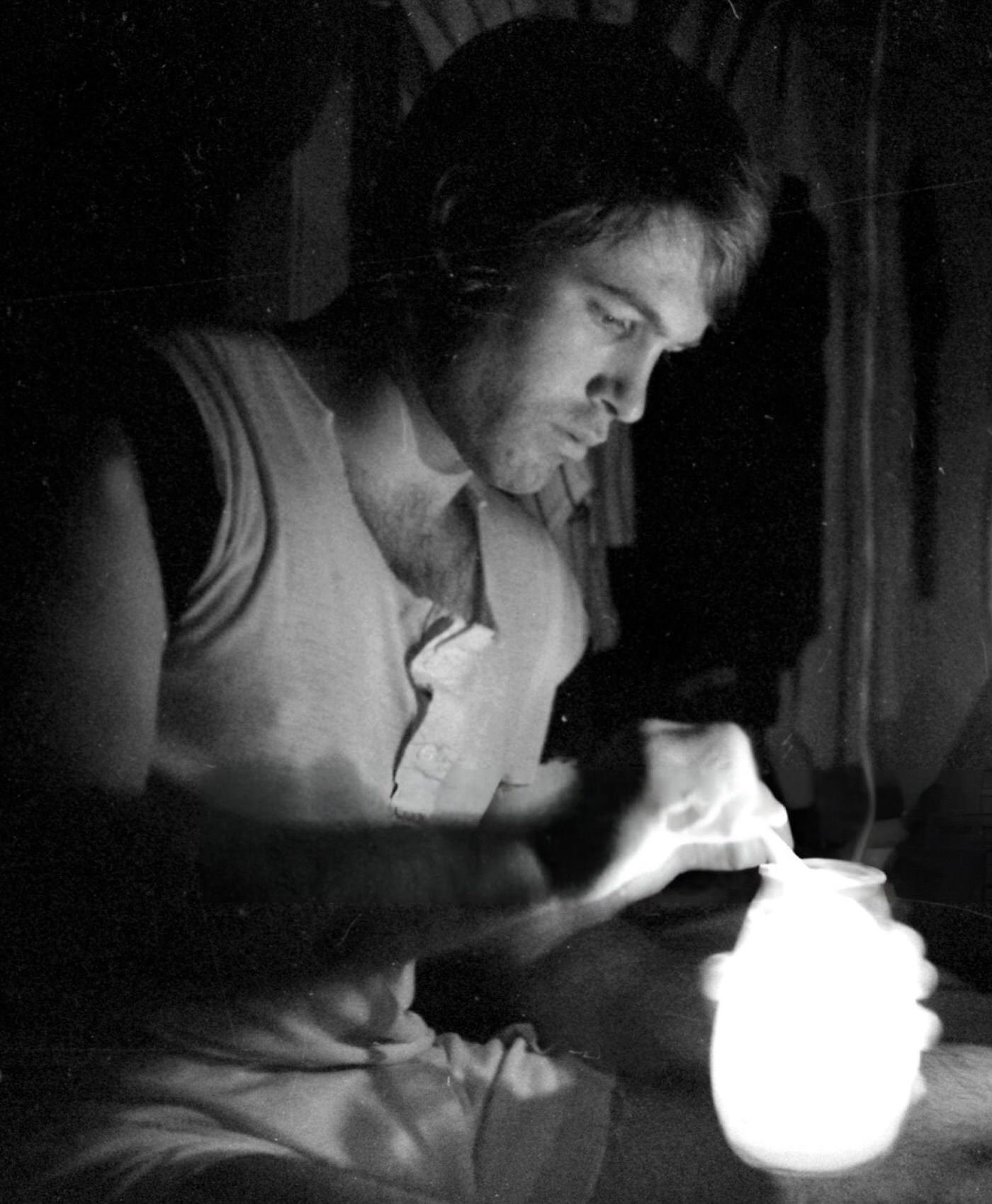

The summer of 1977 was hot and tense in New York City. A strong heatwave hit the East Coast, with temperatures soaring into the 90s. People turned on air conditioners and fans, which put stress on the power system. At the same time, the city was in trouble. New York was almost out of money. City services were cut, and many people were struggling, especially in poorer areas. Crime was going up. People were scared because a serial killer, known as the “Son of Sam,” was still on the loose. All of this made the city feel uneasy. In places like the Bronx, where poverty was common, the tension felt even worse. When the power went out that July, the city did not stay calm like it had during the blackout in 1965. This time, things turned chaotic.

The Spark: Lightning Ignites the Crisis

The chain reaction began on the hot, humid evening of Wednesday, July 13, 1977. A severe thunderstorm rolled over Westchester County, just north of the city. Around 8:37 PM Eastern Daylight Time, lightning delivered the first blow, striking the Buchanan South substation on the Hudson River. This critical facility converted high-voltage electricity—345,000 volts—coming from the large Indian Point nuclear power plant, stepping it down for distribution. The lightning strike immediately tripped two circuit breakers, interrupting the flow of power. This single natural event targeted a vital point in the Consolidated Edison (Con Edison) power system, the company supplying electricity to New York City and parts of Westchester.

Domino Effect: The Grid Begins to Fail

What should have been a manageable disruption quickly escalated due to a combination of factors. At the Buchanan South substation, a crucial circuit breaker failed to automatically reconnect power. A simple loose locking nut, combined with a slow-acting equipment upgrade cycle, prevented the breaker from reclosing as it should have. This mechanical failure compounded the initial problem.

Read more

Moments later, a second lightning strike hit, knocking out two major 345 kV transmission lines carrying power from Indian Point. Only one of these lines successfully reclosed, further straining the remaining pathways. The system was losing both power generation from Indian Point and the lines needed to transport electricity.

Then, at 8:55 PM, a third lightning strike hit another key location: the Sprain Brook substation in Yonkers. This disabled two more critical transmission lines. System protective measures, designed primarily to safeguard the Indian Point plant itself, meant that only one of these lines automatically returned to service. While protecting the nuclear facility, this design choice inadvertently placed an even heavier burden on the rest of the already overloaded Con Edison grid. Within twenty minutes, multiple lightning strikes and equipment issues had severely damaged the network bringing power into the city from the north.

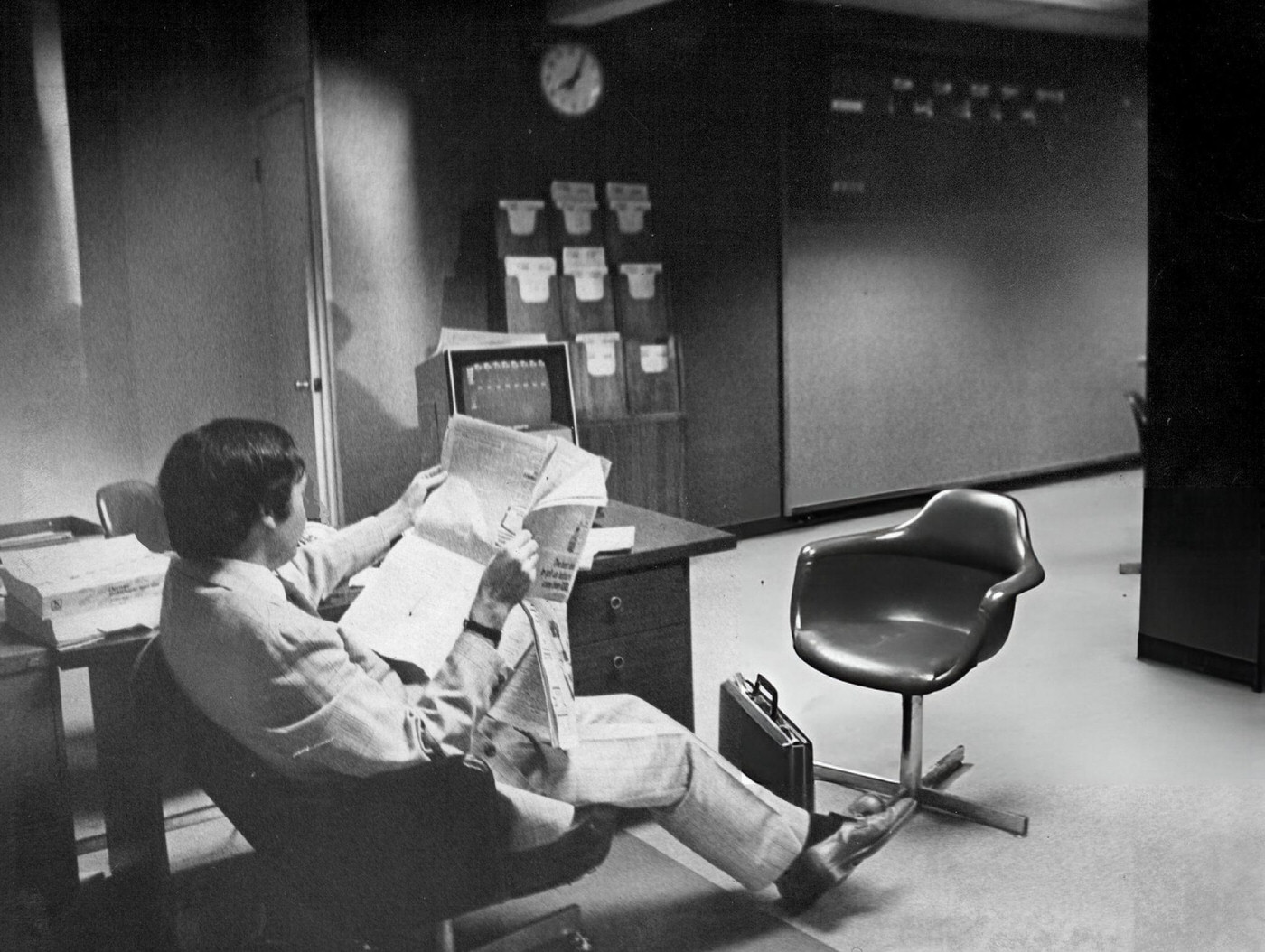

Too Little, Too Late: Attempts to Control the Cascade

Con Edison operators scrambled to respond to the escalating crisis. An attempt to remotely start backup generators at 8:45 PM failed because the station was unmanned. As transmission lines overloaded, operators needed to reduce demand quickly. Around 9:08 PM, they initiated system-wide voltage reductions, first by 5 percent, then by 8 percent. However, this method shed load too slowly compared to the rapid loss of transmission capacity. The New York Power Pool, overseeing the regional grid, had recommended faster action, like immediately disconnecting, or “shedding,” large blocks of customers, but communication issues and differing interpretations of procedure hampered the response. Evidence suggests operators may not have been adequately trained for such a complex emergency, and standard operating procedures were lacking or not followed effectively.

The slow response could not prevent further collapse. At 9:19 PM, the main interconnection carrying power from upstate New York via the Leeds substation tripped offline due to the massive overload. Power surges then overloaded connections to neighboring utilities. At 9:22 PM, the Long Island Lighting Company (LILCO), trying to protect its own system from the instability, opened its connection to Con Edison. Con Edison operators attempted to manually shed load around 9:24 PM, but this effort failed, possibly due to equipment malfunction or improper operation. The final lifeline severed at 9:29 PM when the Goethals-Linden interconnection to New Jersey tripped. Con Edison was now completely isolated, an electrical island cut off from all external power sources.

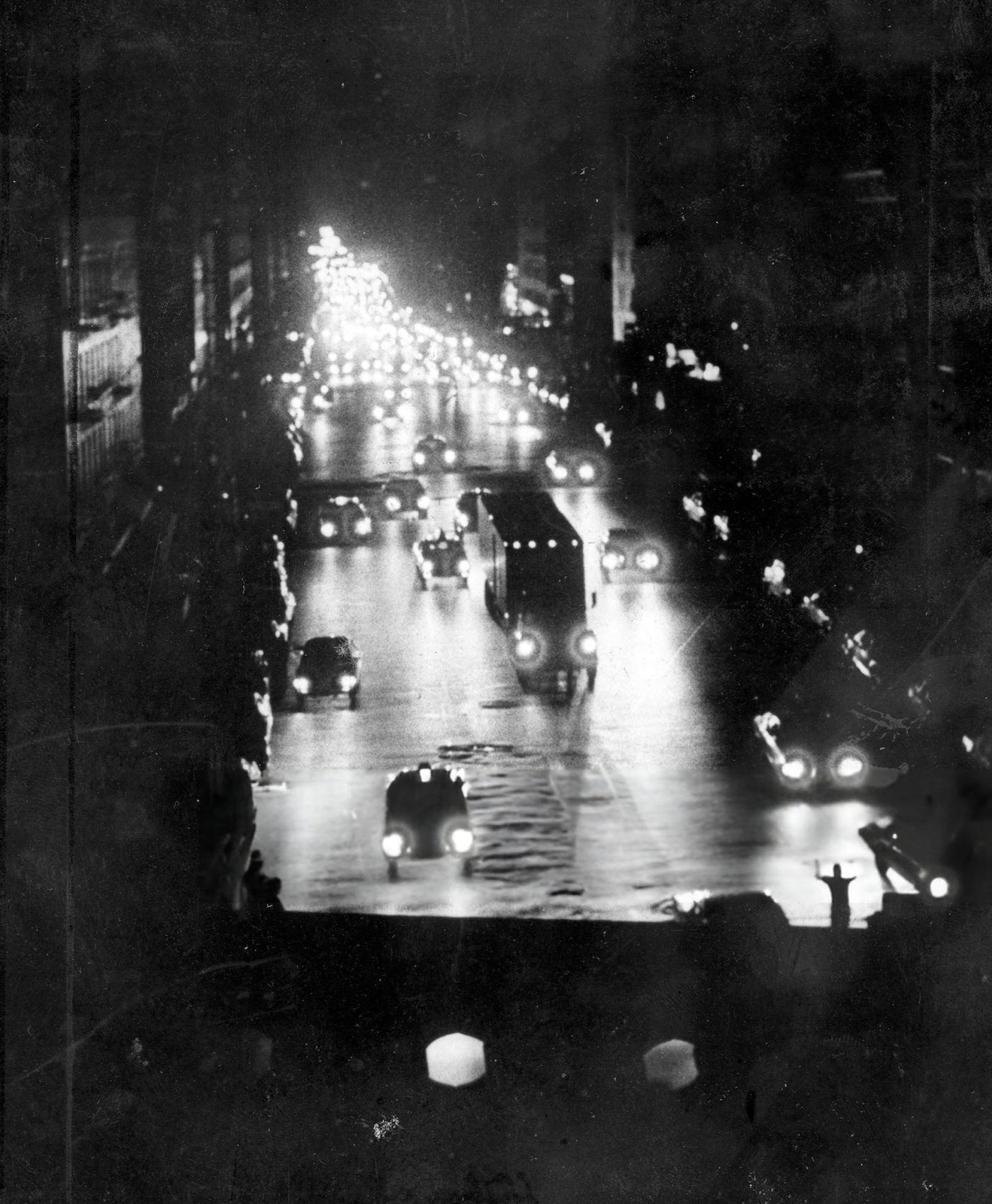

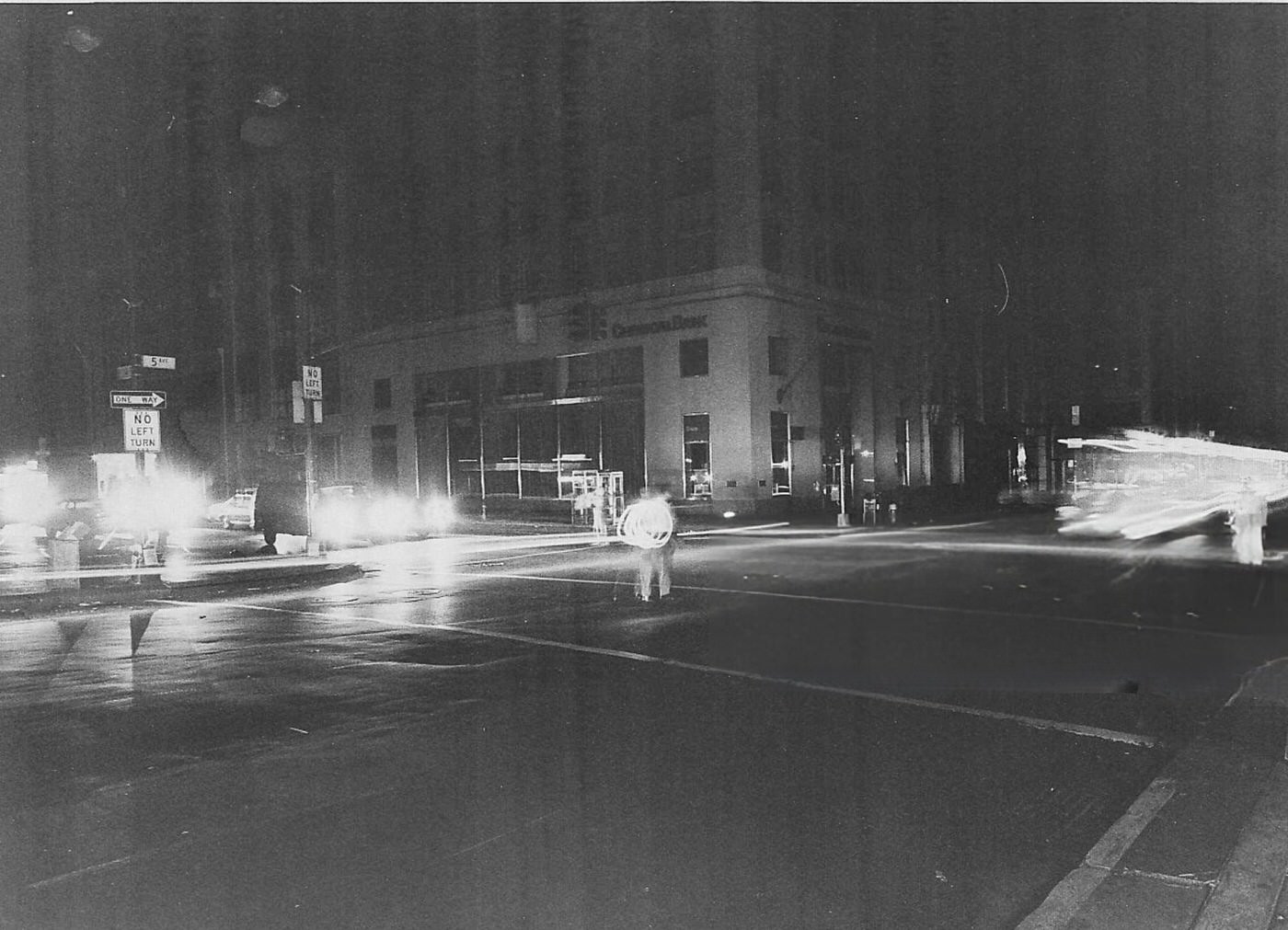

Isolated and losing power sources, the Con Edison system became fatally unstable. The frequency and voltage fluctuated wildly. Just after 9:28 PM, the system’s largest internal generator, the 990-megawatt Ravenswood Unit 3 in Queens, known as “Big Allis,” automatically shut down to protect itself. Its loss removed the last major source of power generation within the city. The collapse was now unavoidable. By 9:37 PM on July 13, almost exactly one hour after the first lightning strike, the entire Con Edison power system shut down. New York City was plunged into darkness.

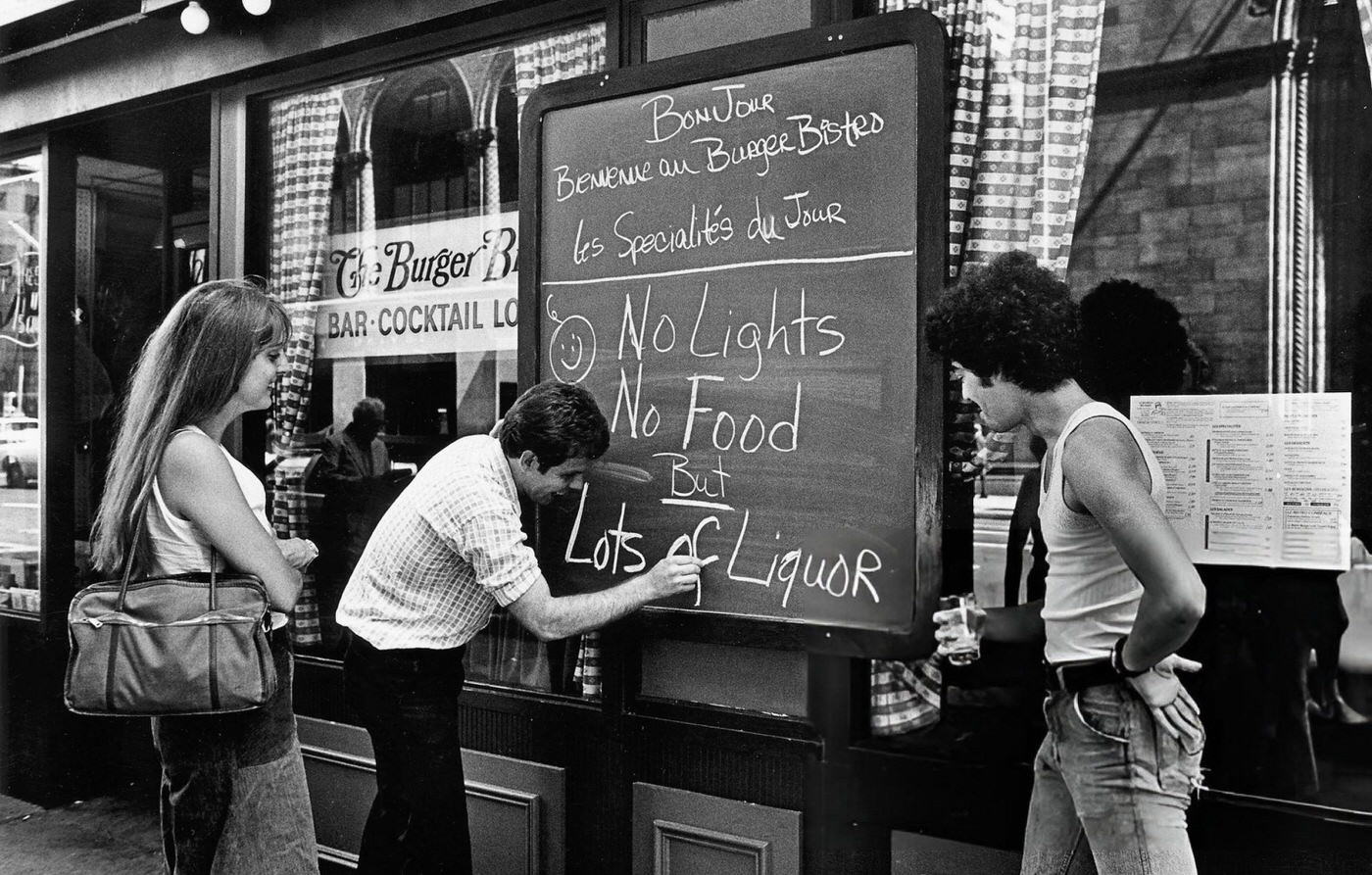

Immediate Shutdown: Infrastructure Grinds to a Halt

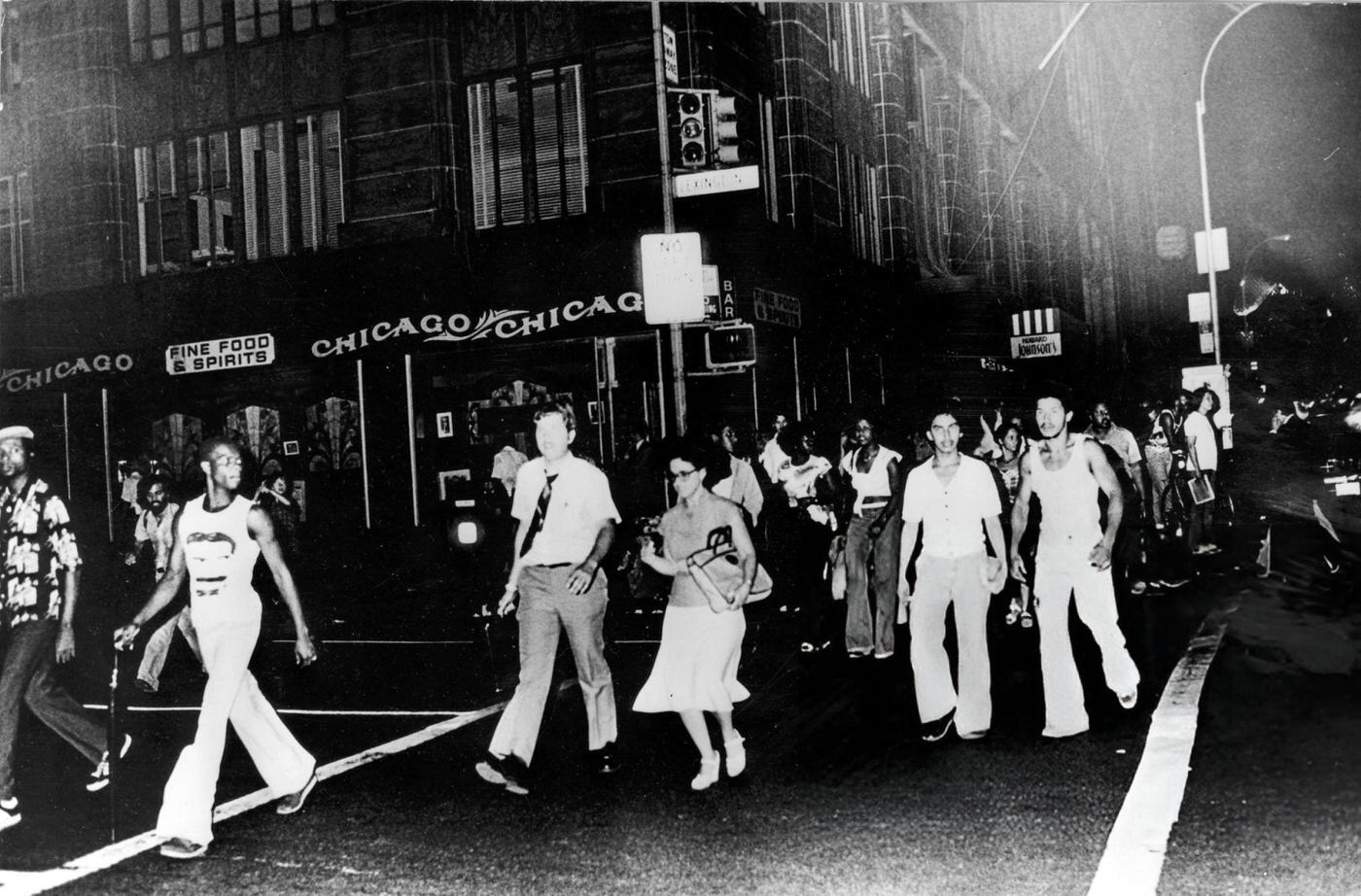

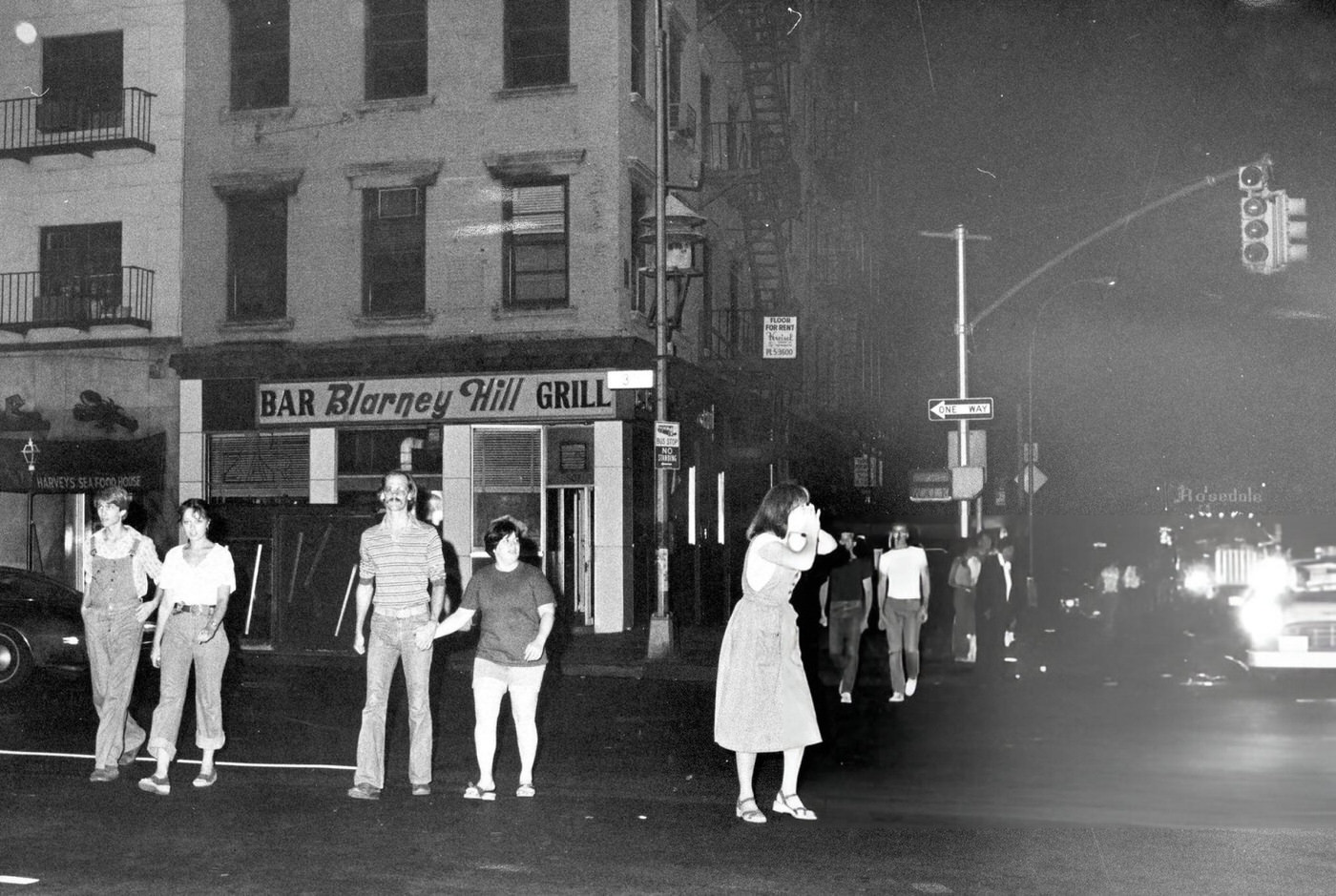

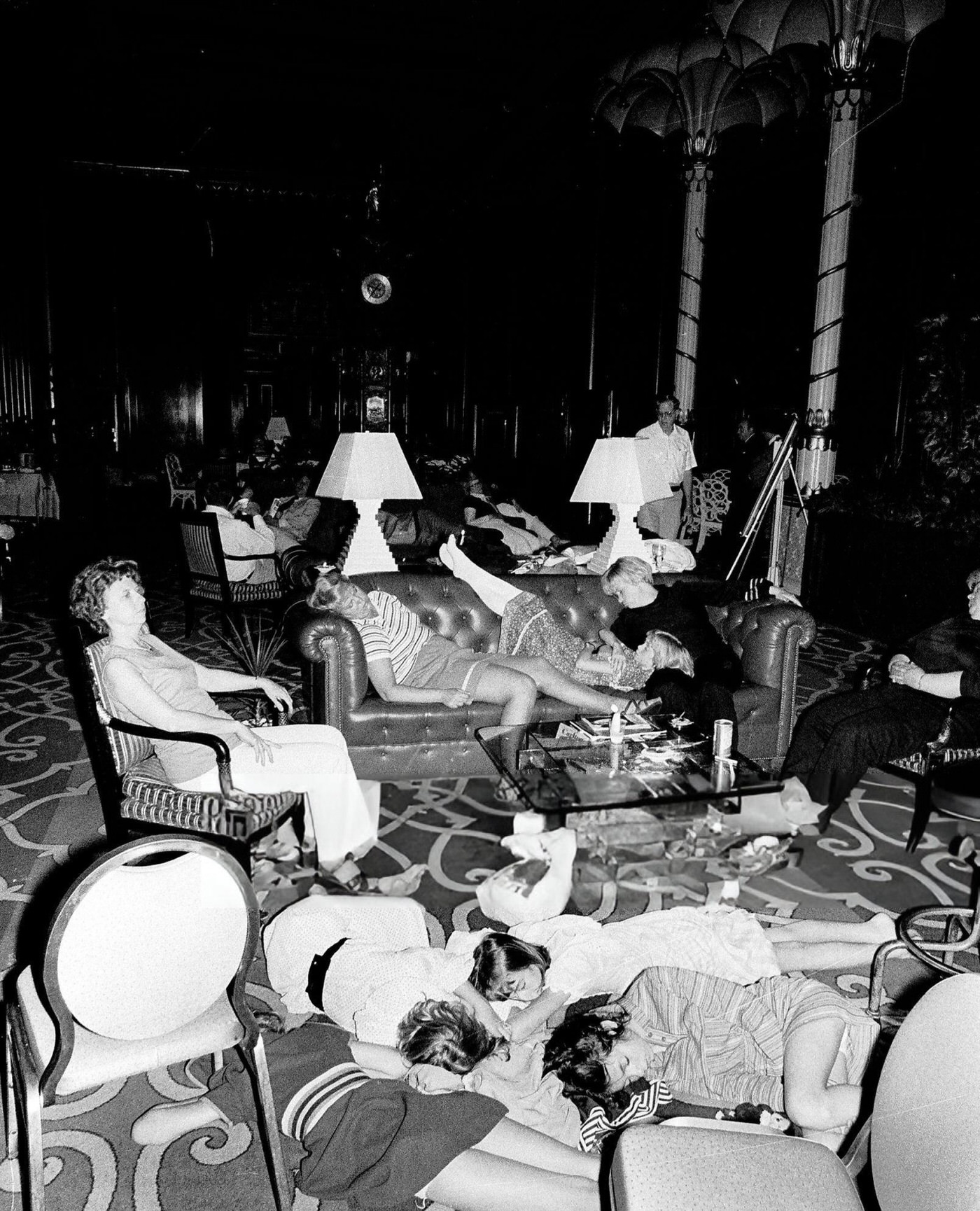

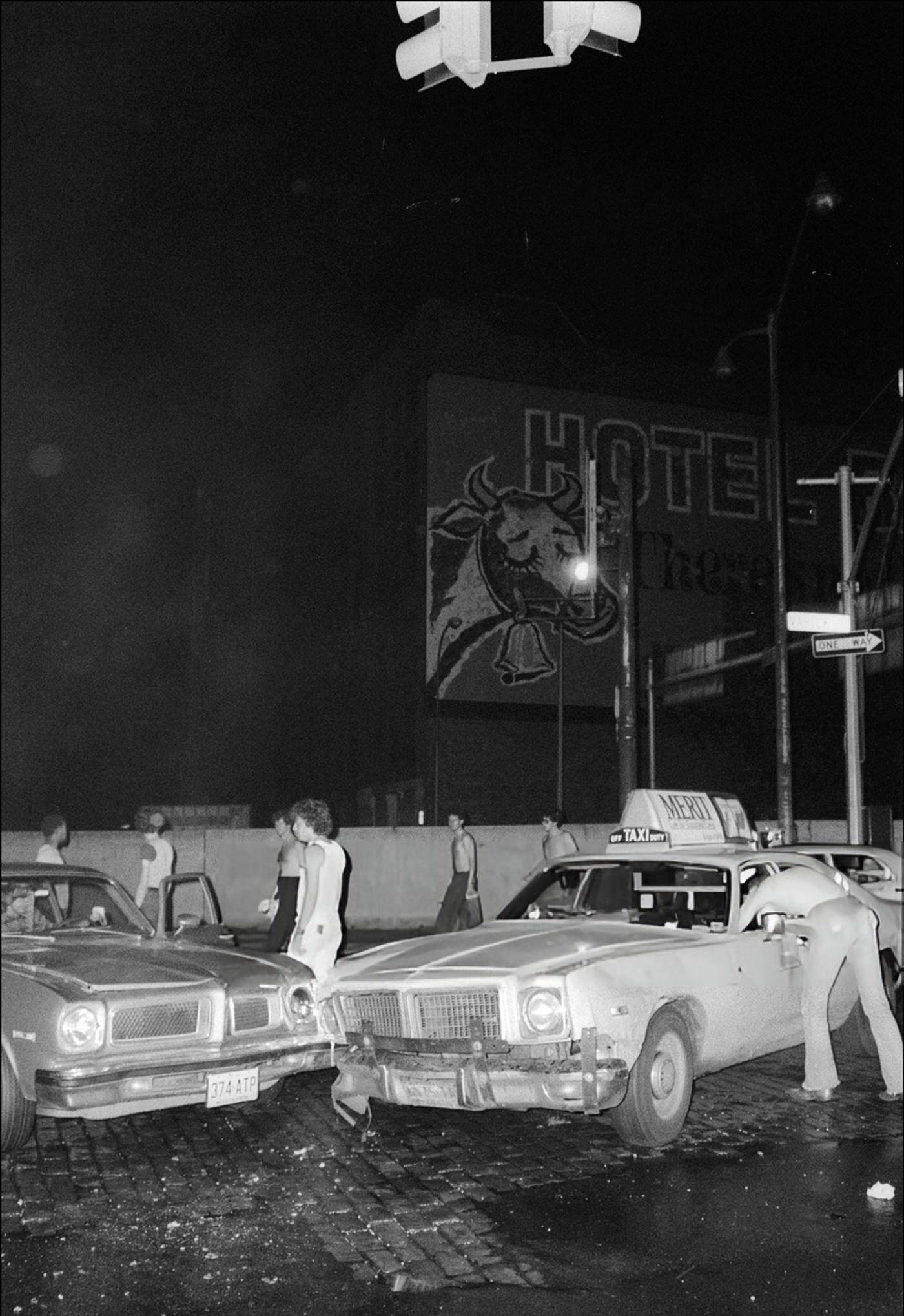

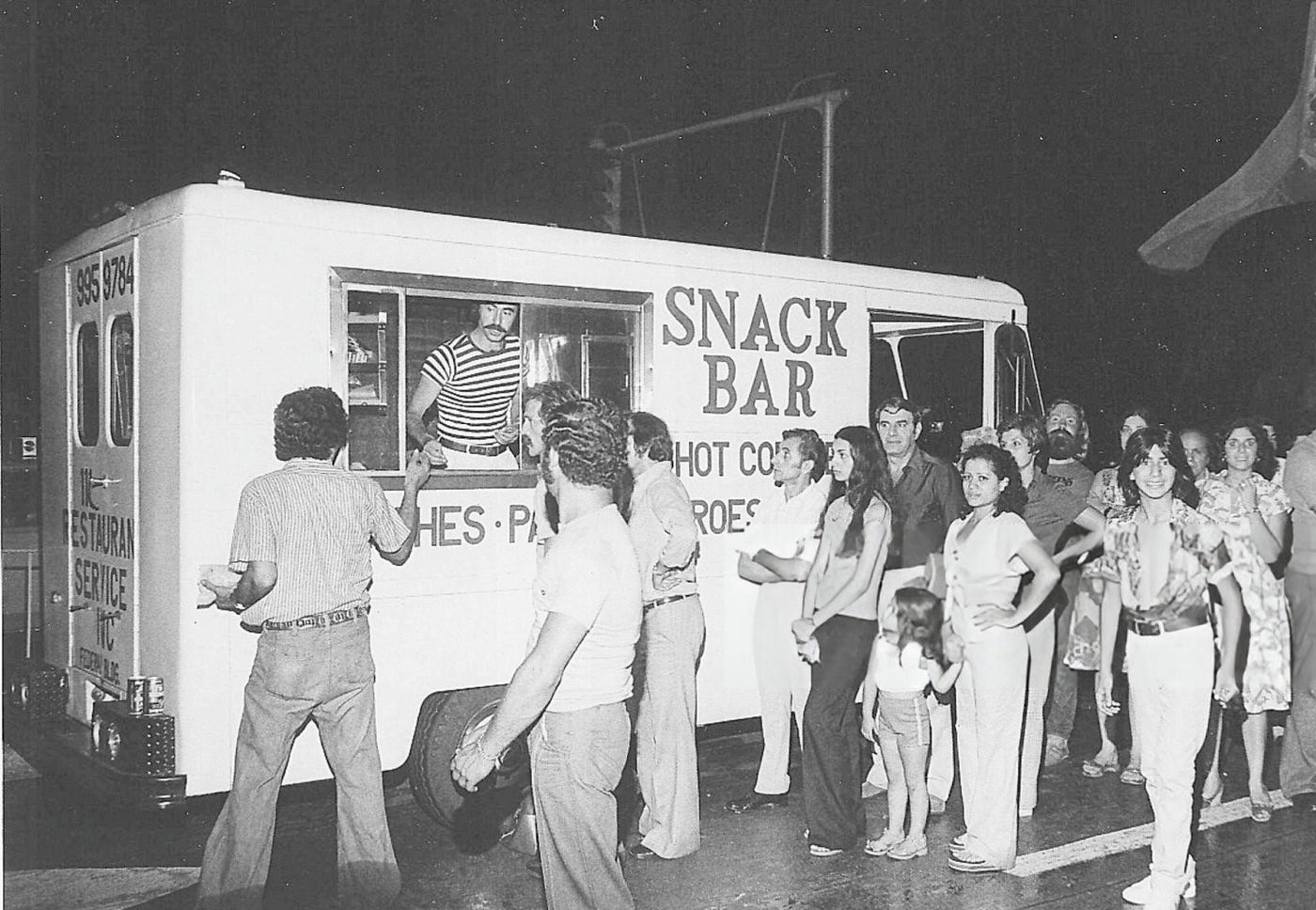

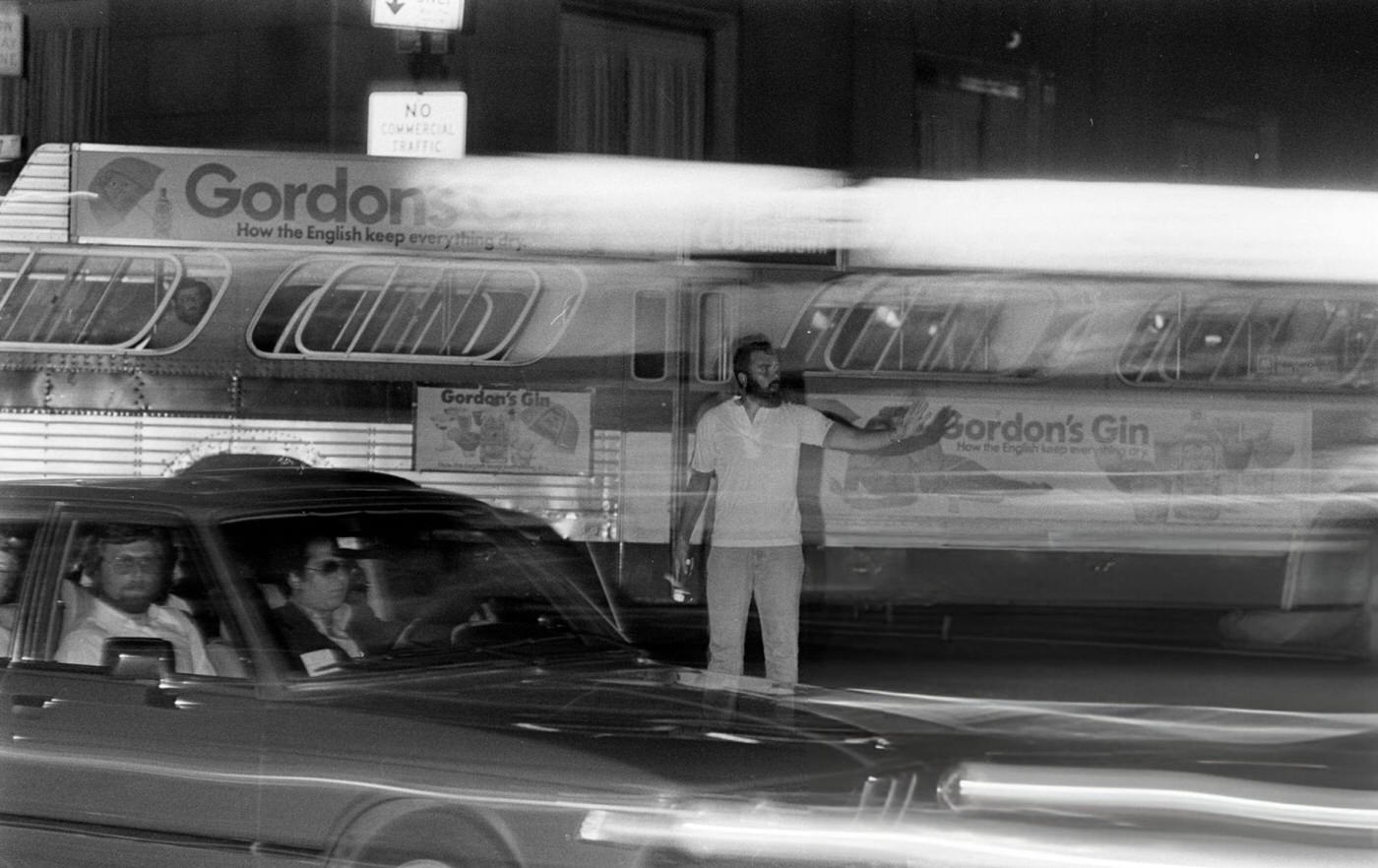

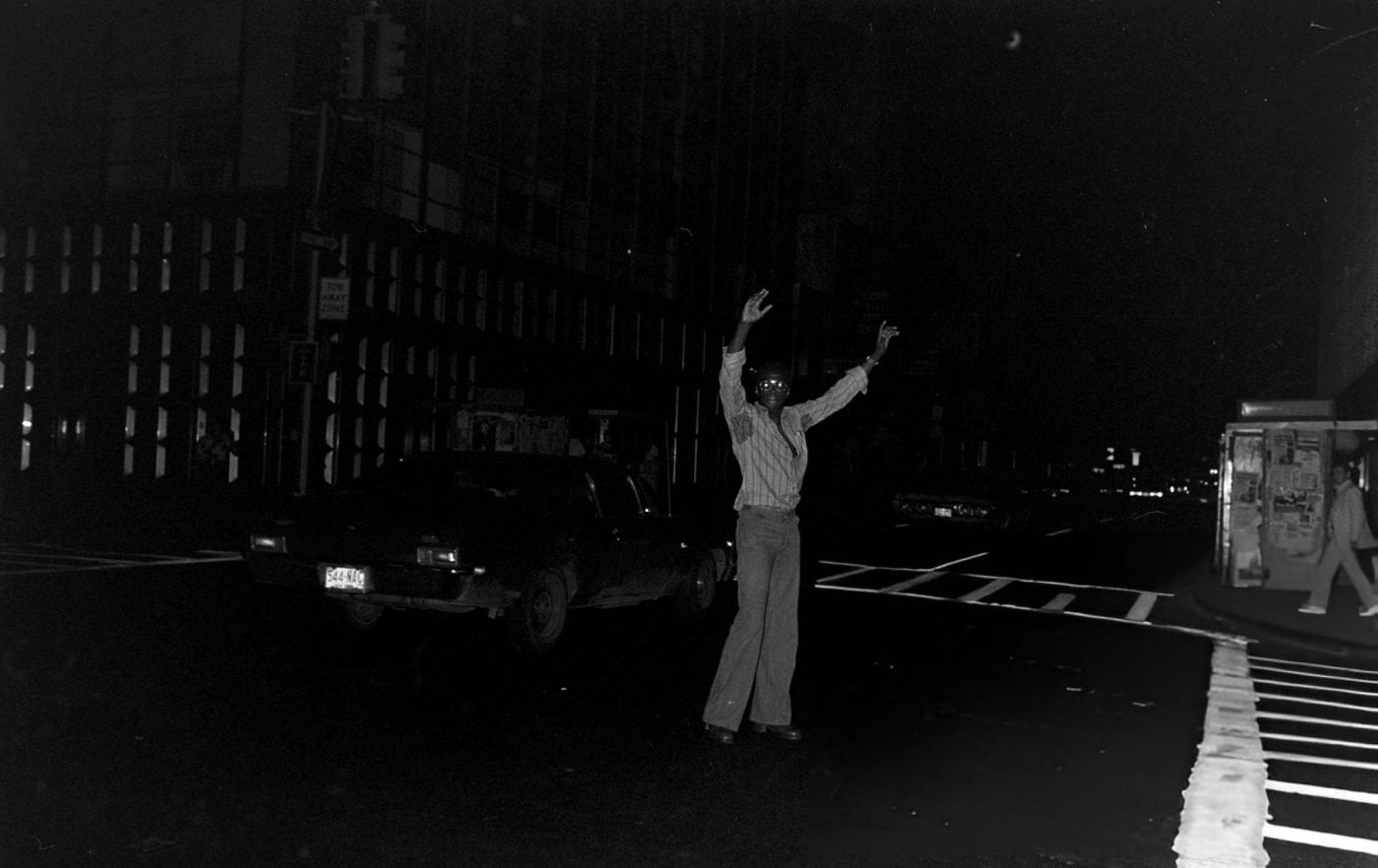

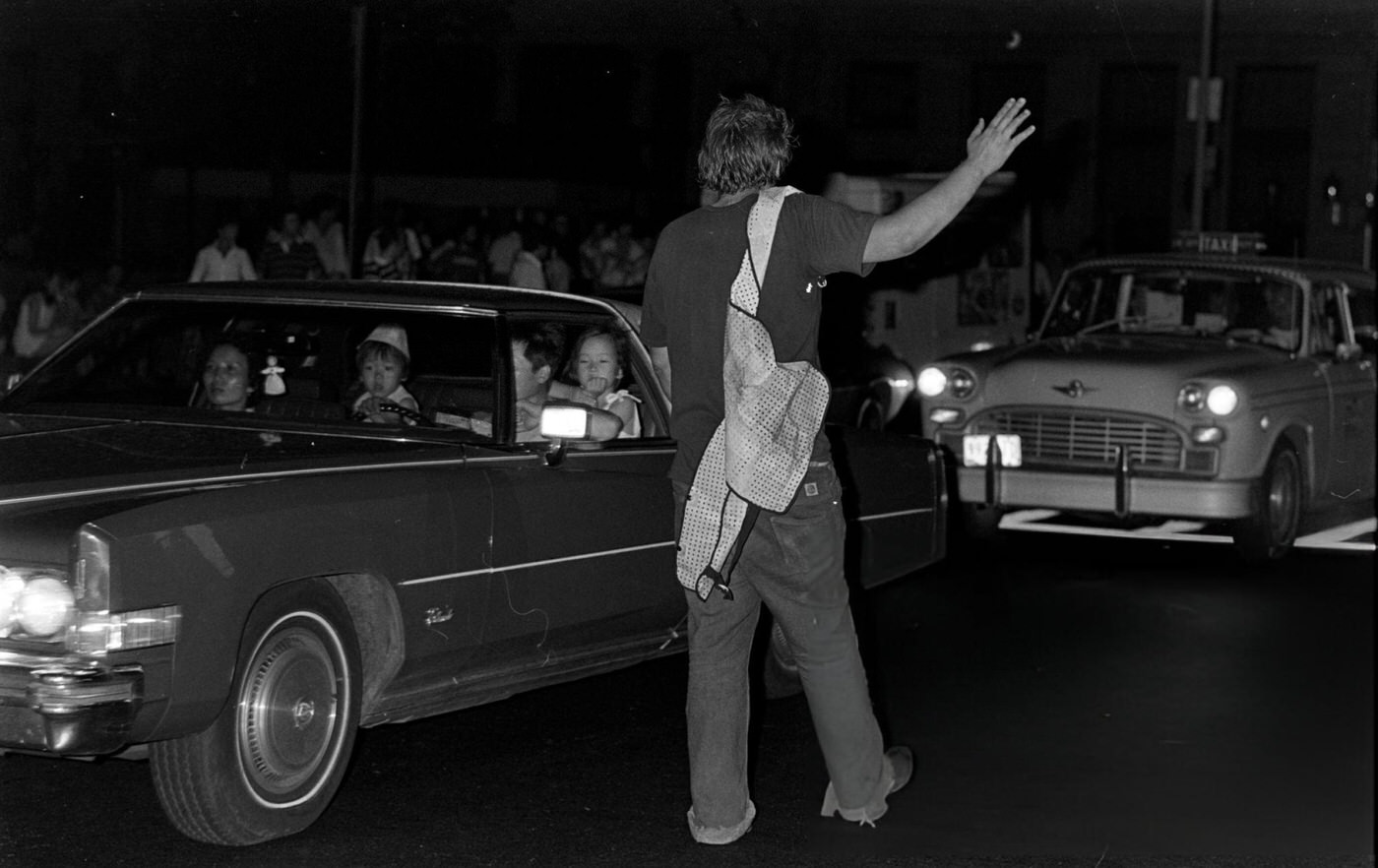

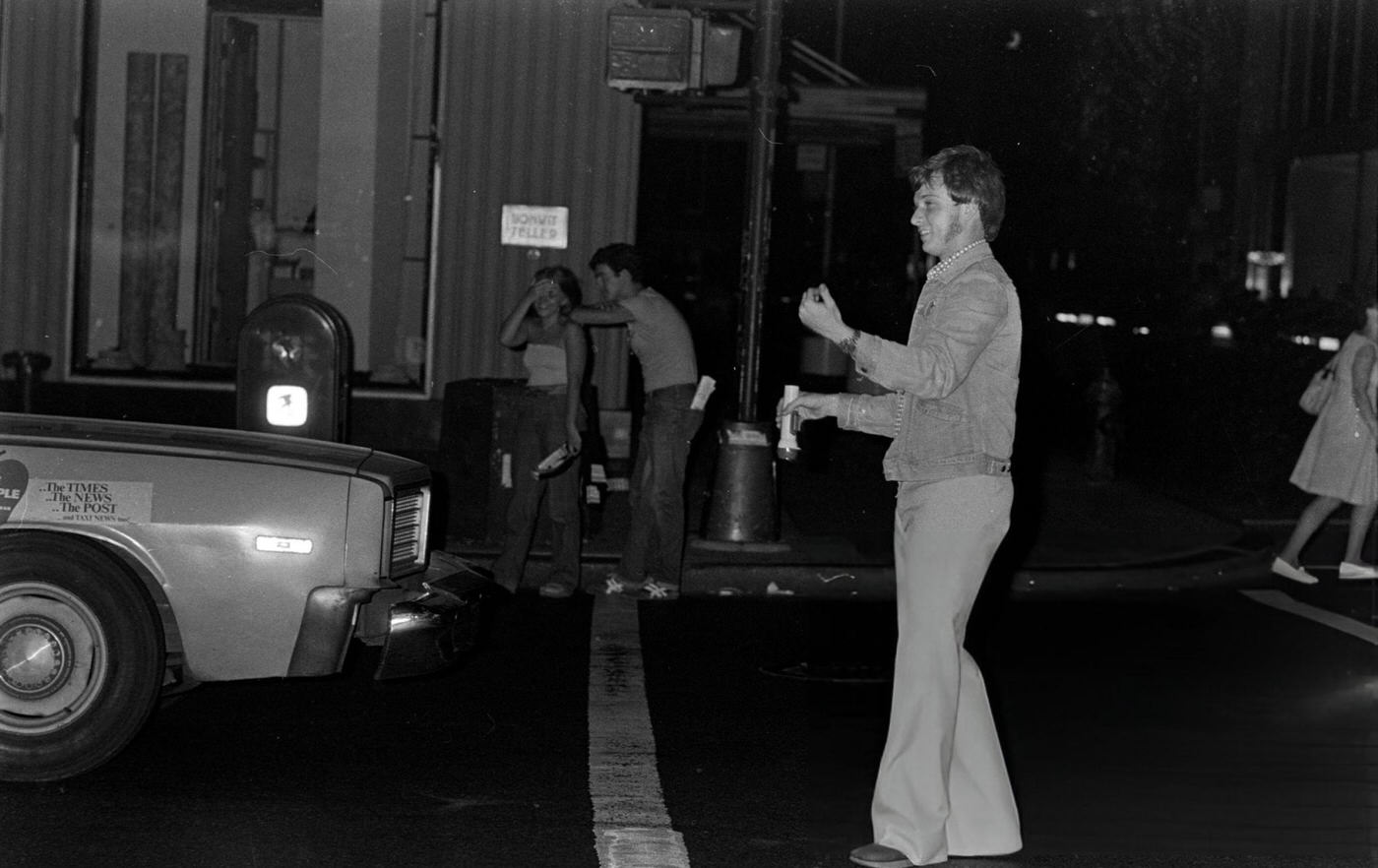

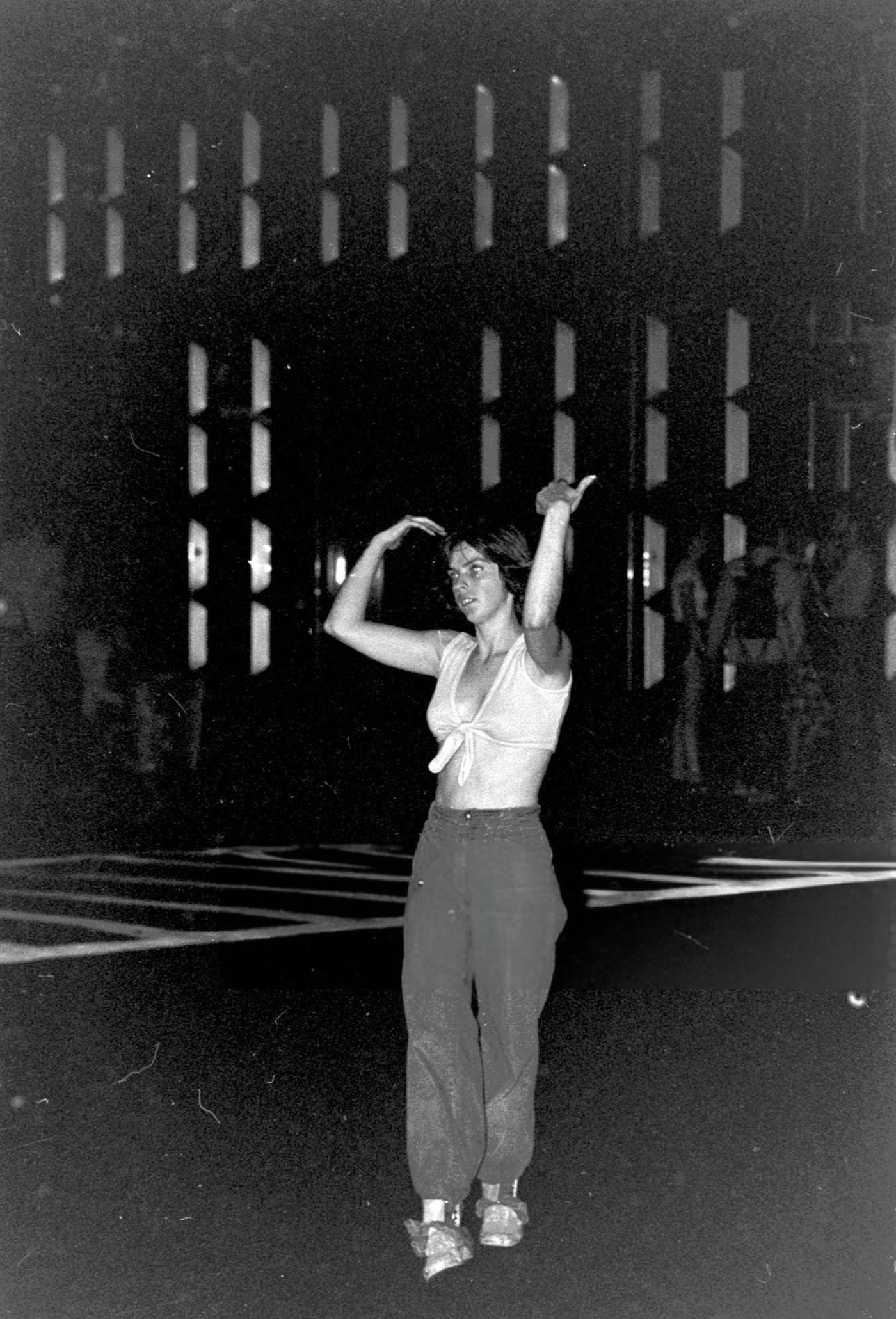

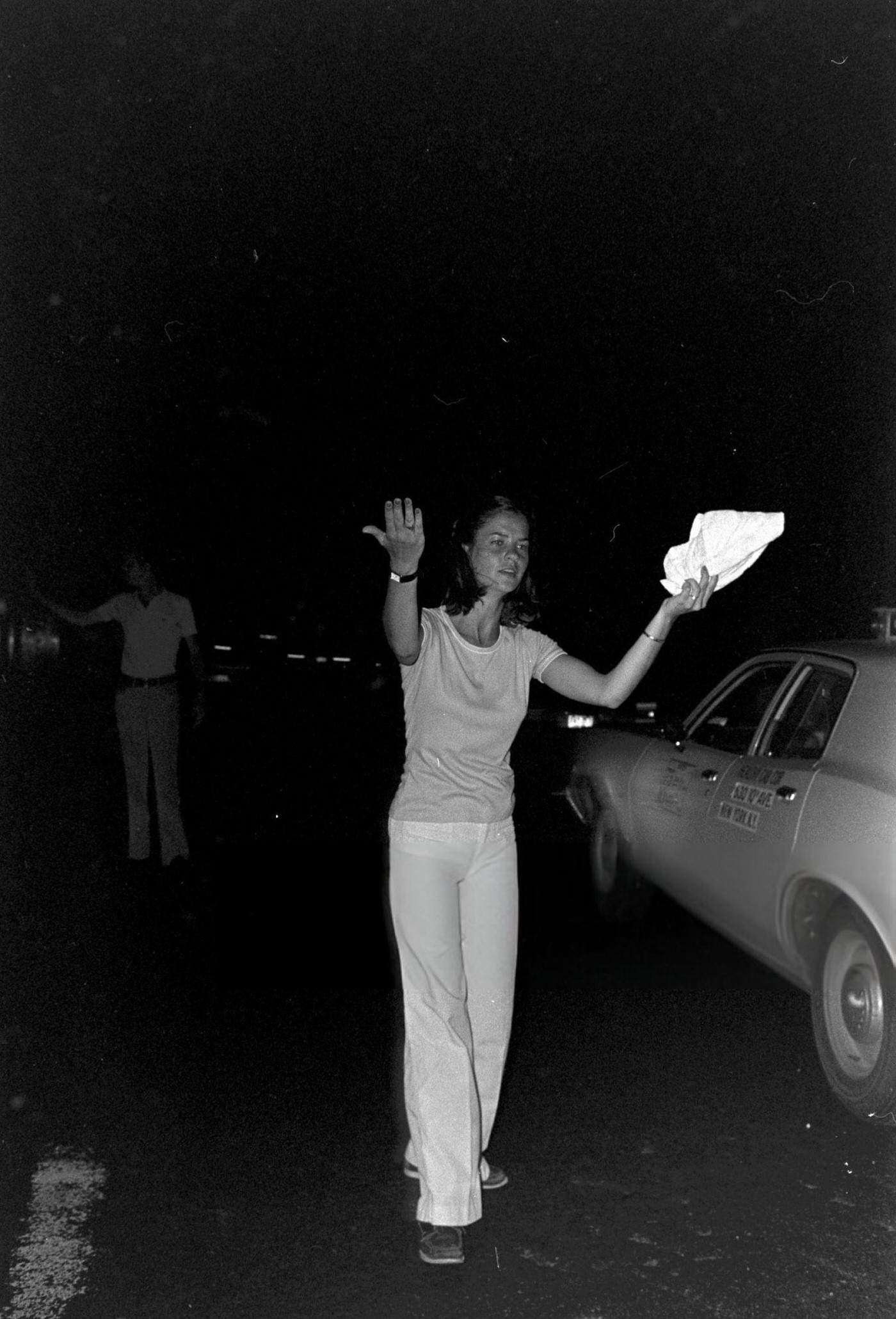

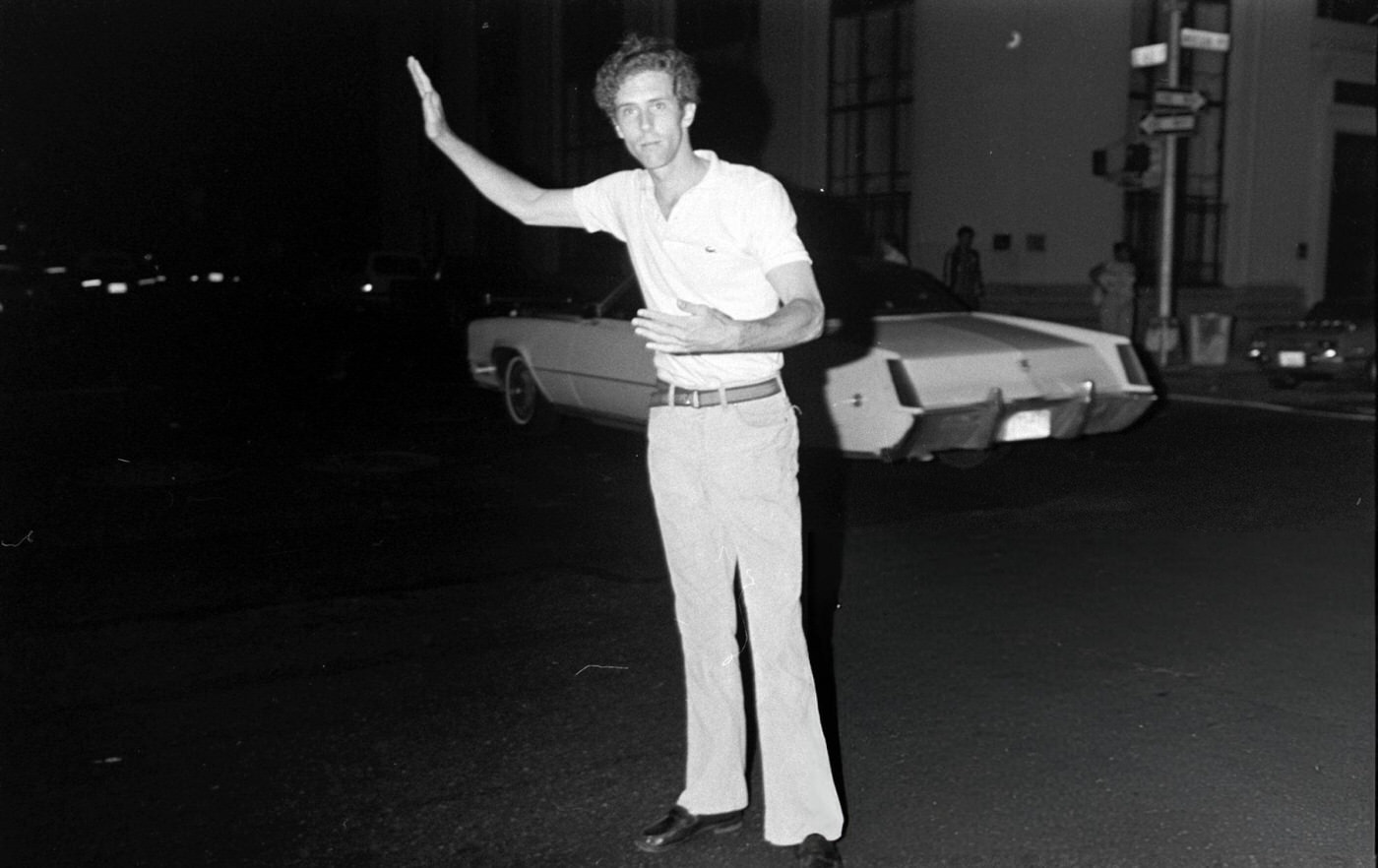

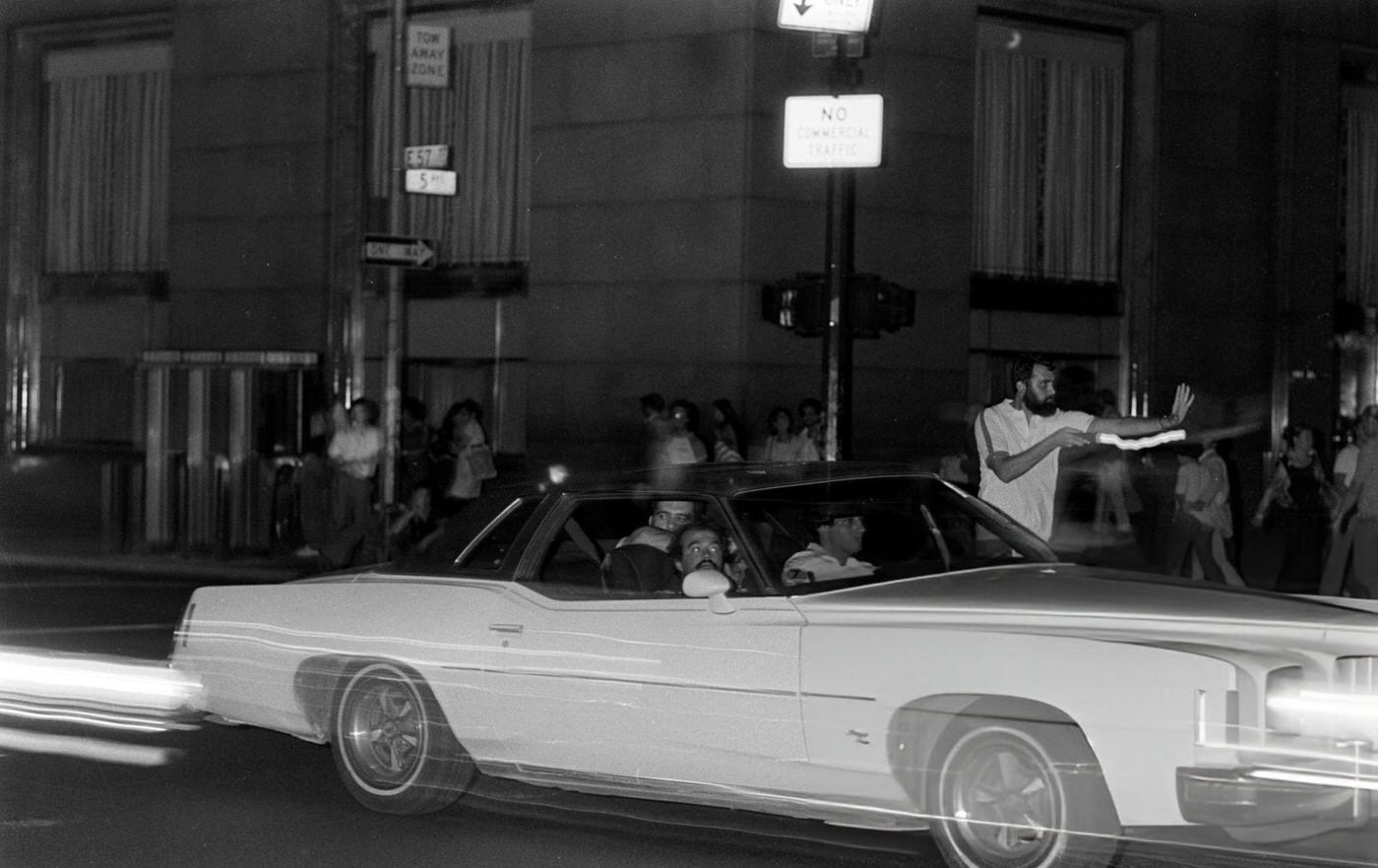

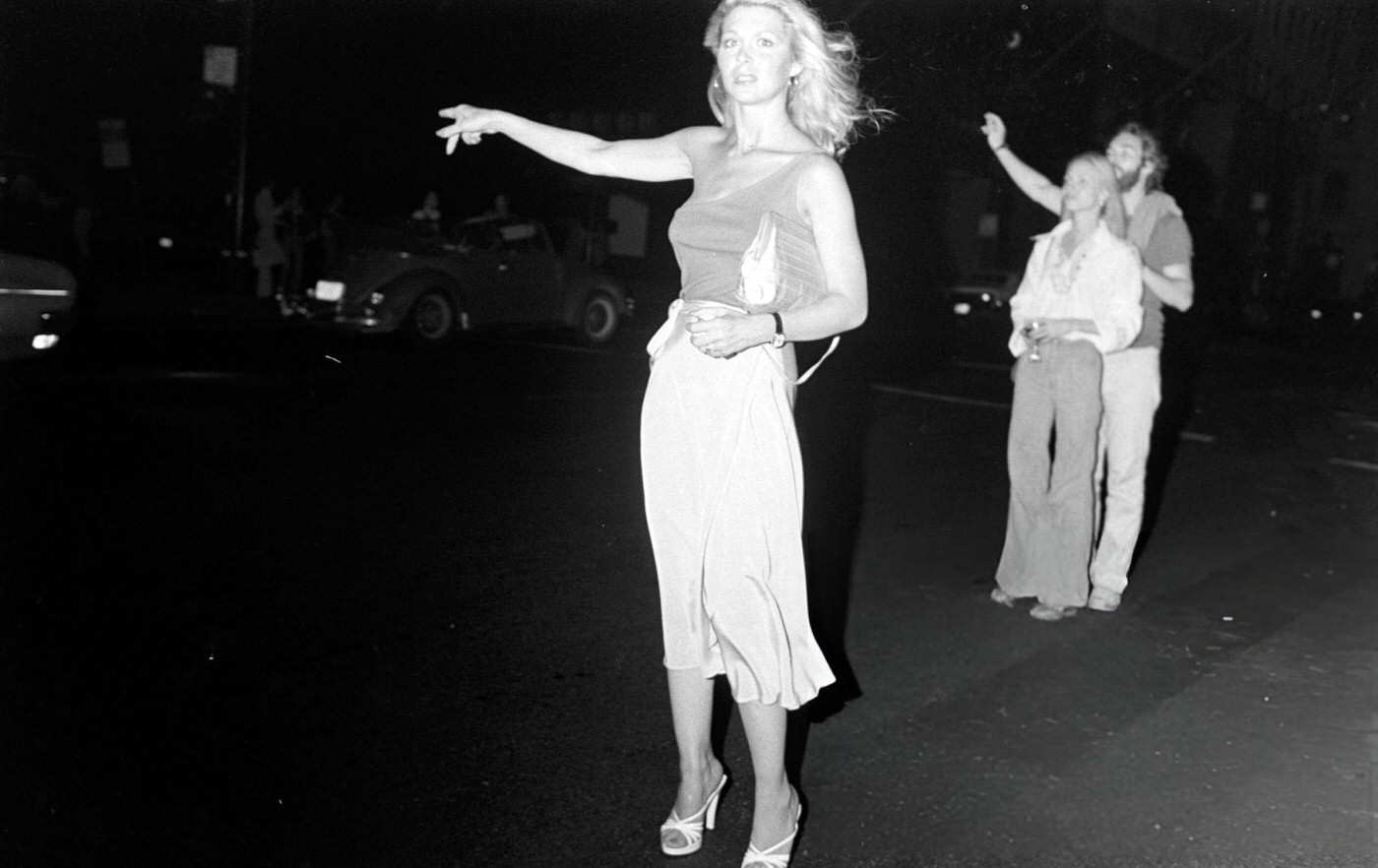

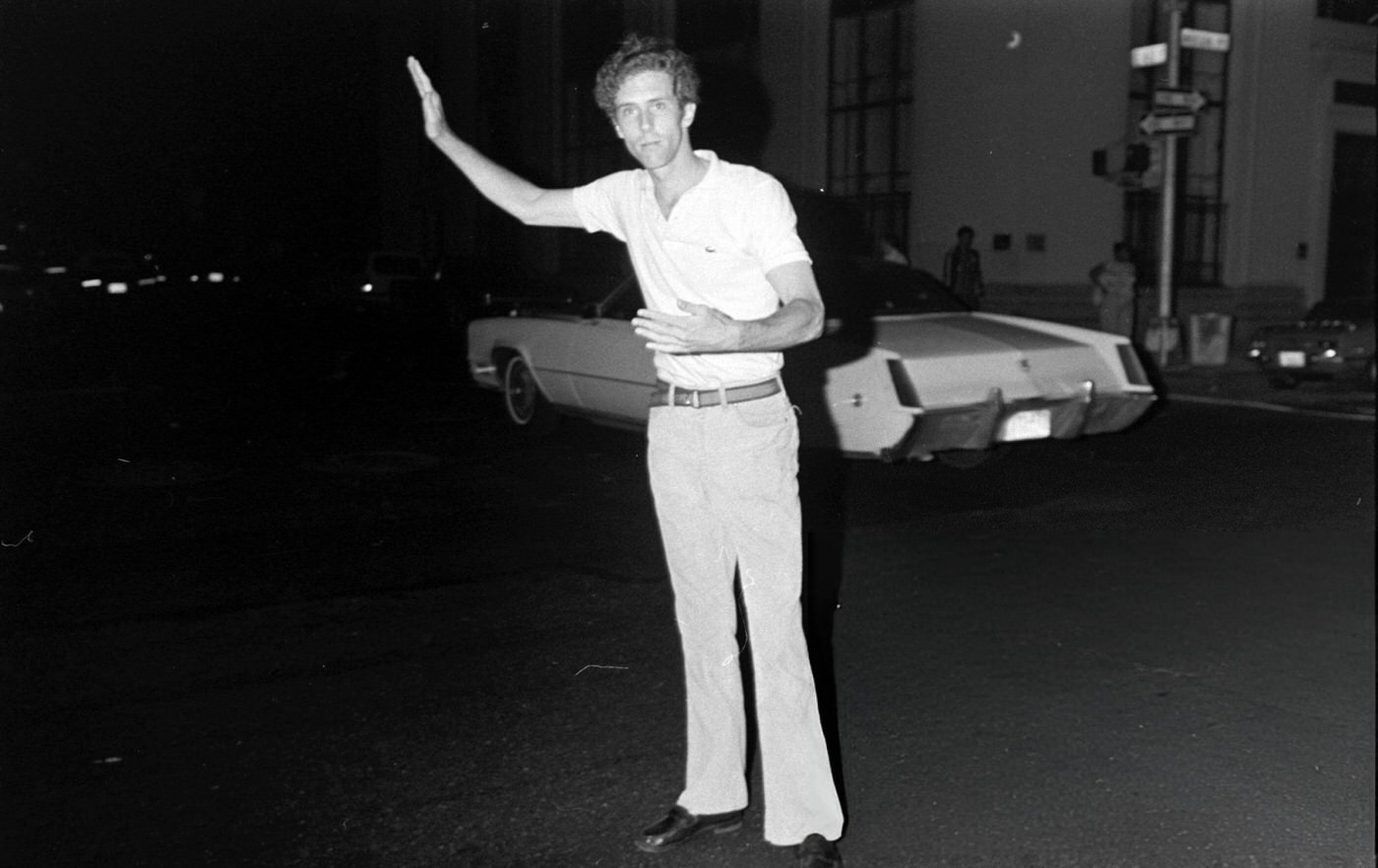

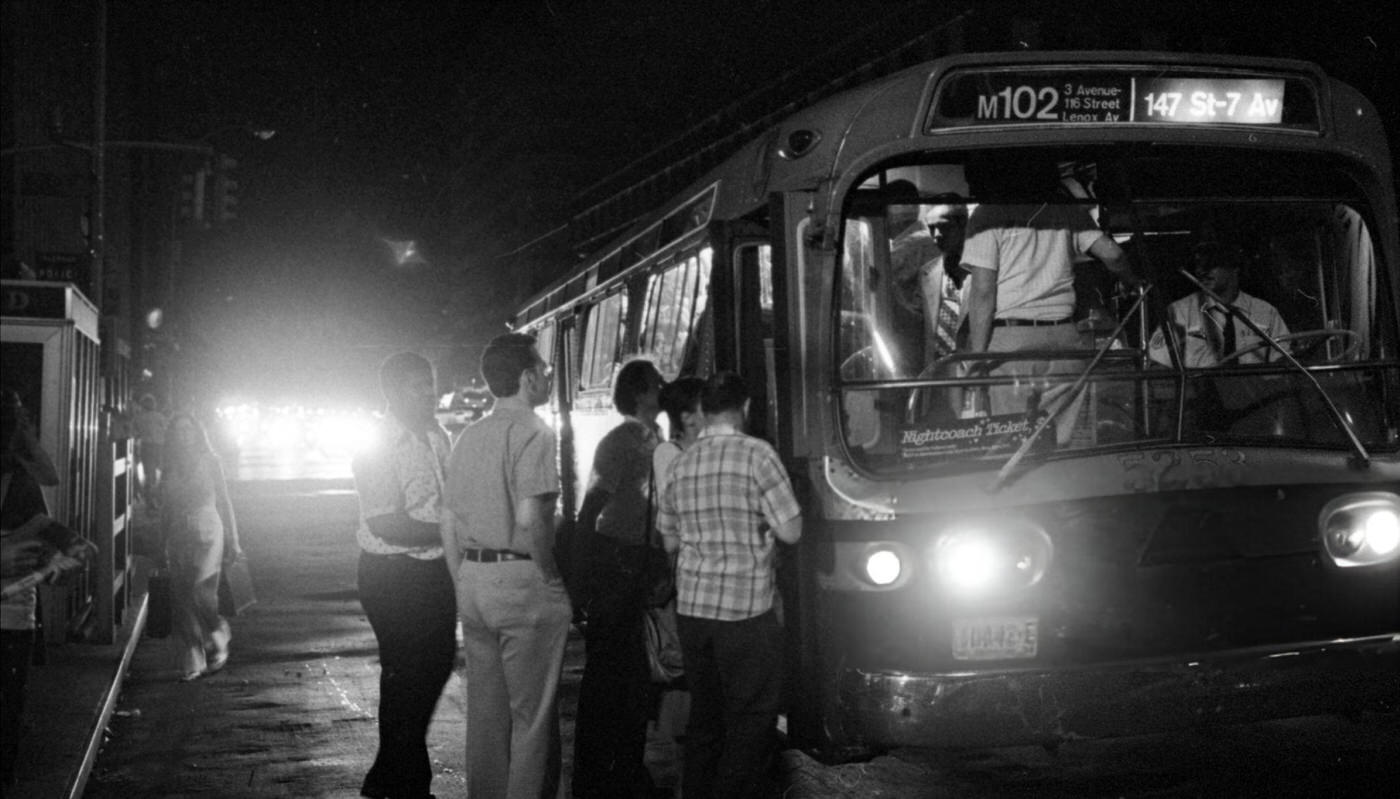

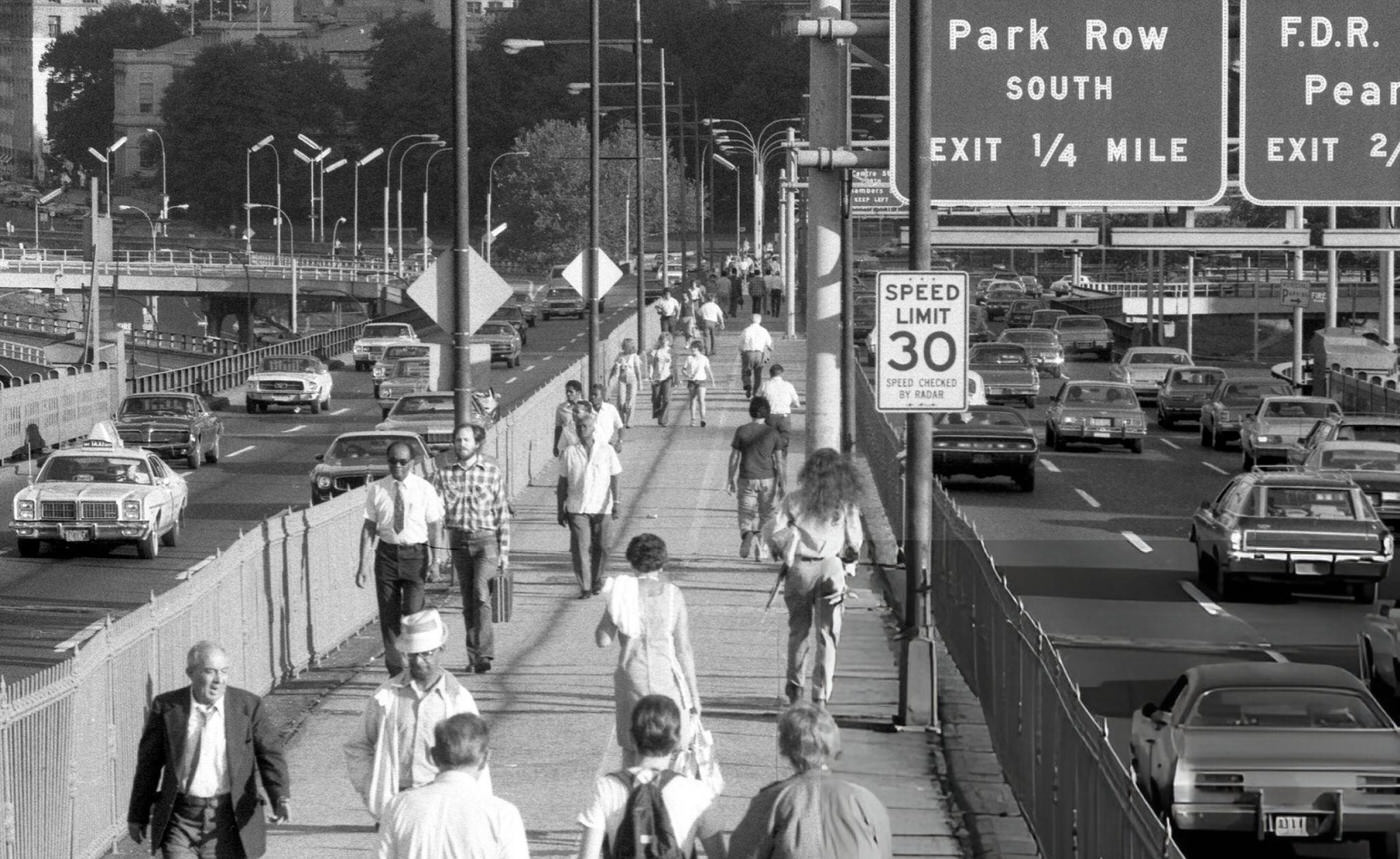

The effect was instantaneous and city-wide. Lights blinked out across Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and parts of Westchester County. Only areas served by different utilities, like southern Queens and the Rockaways (powered by LILCO), remained lit. The oppressive heatwave became unbearable as air conditioners and fans fell silent. Critical city infrastructure ceased functioning. The subway system ground to a halt, trapping commuters underground; ultimately, about 4,000 people had to be evacuated from stalled trains. Traffic lights went dark, leading to confusion at intersections, though some citizens spontaneously stepped in to direct vehicles. Both LaGuardia and John F. Kennedy airports were forced to close for approximately eight hours. Automobile tunnels shut down due to the loss of ventilation systems. Thousands of people were trapped in elevators high above the streets. At Shea Stadium, the lights went out during a Mets baseball game, prompting the crowd to sing. Television stations went off the air, and even the bustling financial center of Wall Street was forced to close.

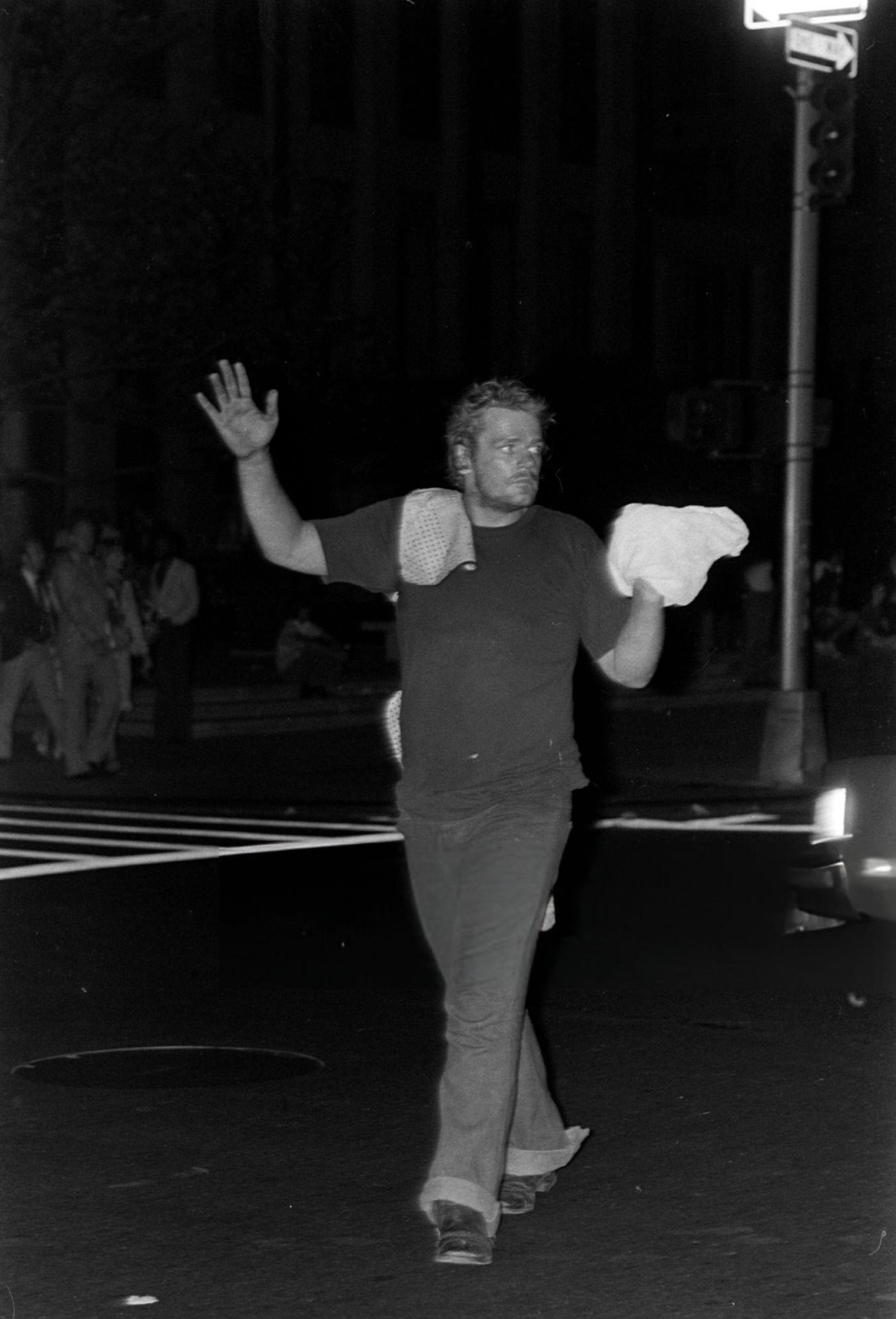

Under the Cover of Darkness: Chaos Unleashed

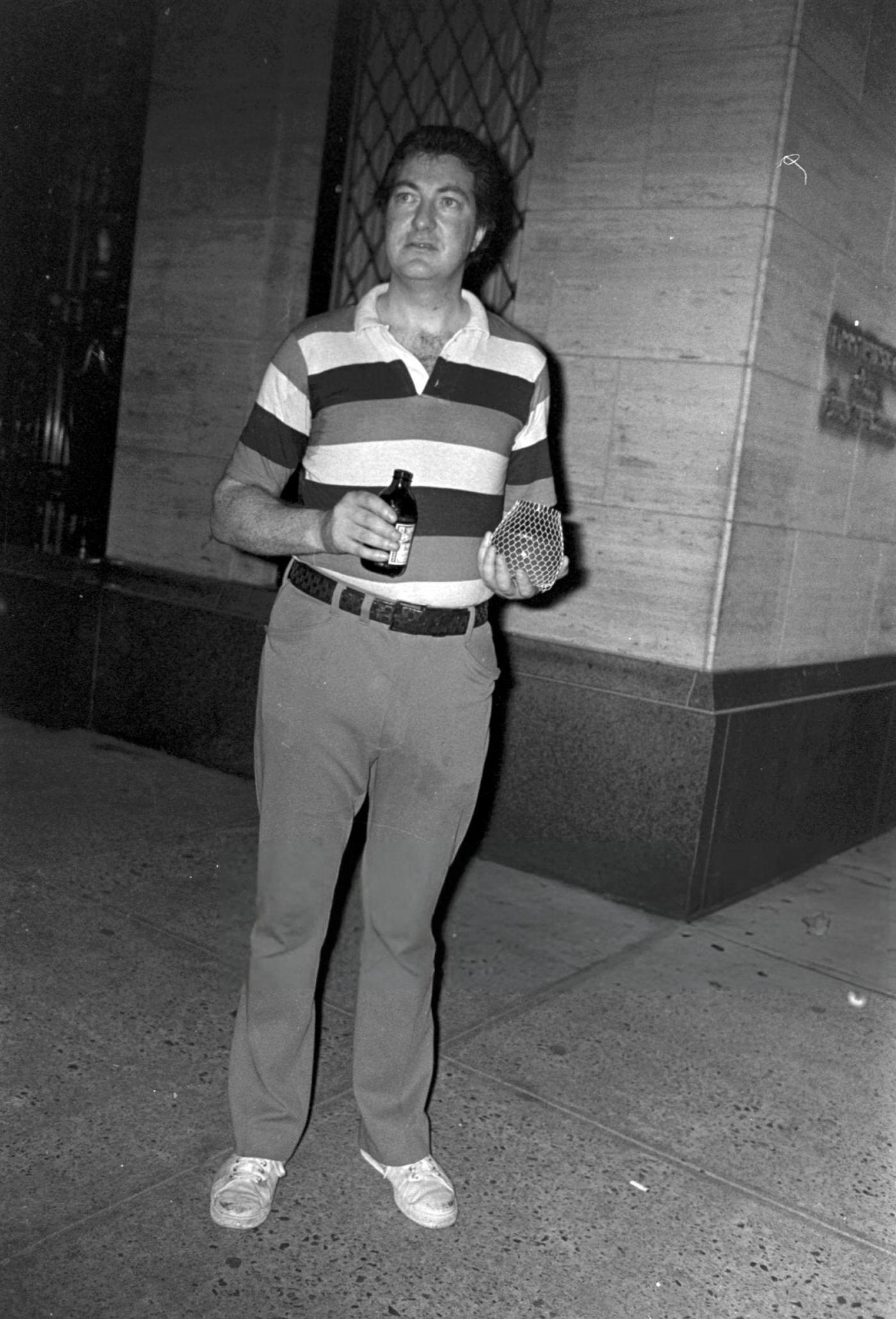

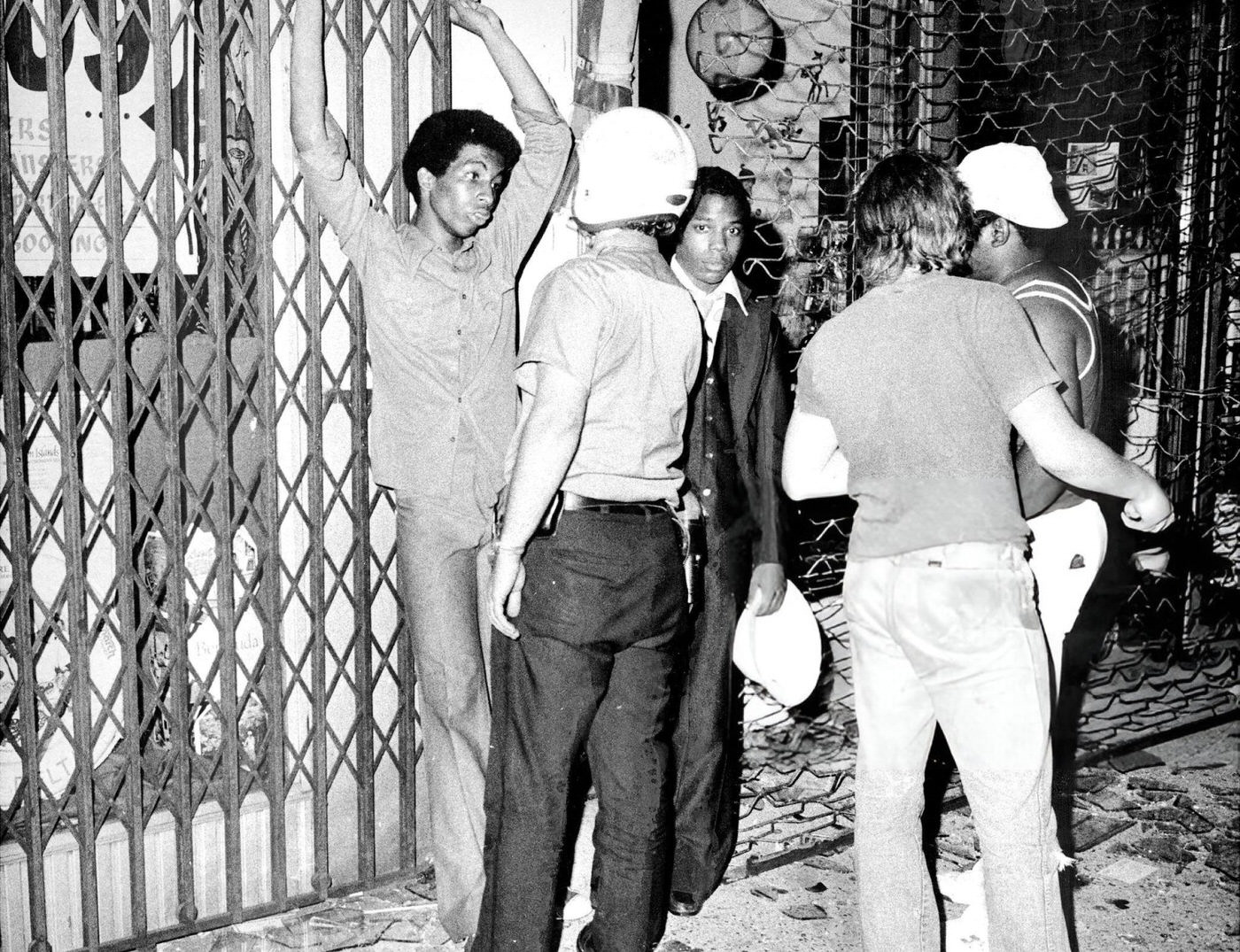

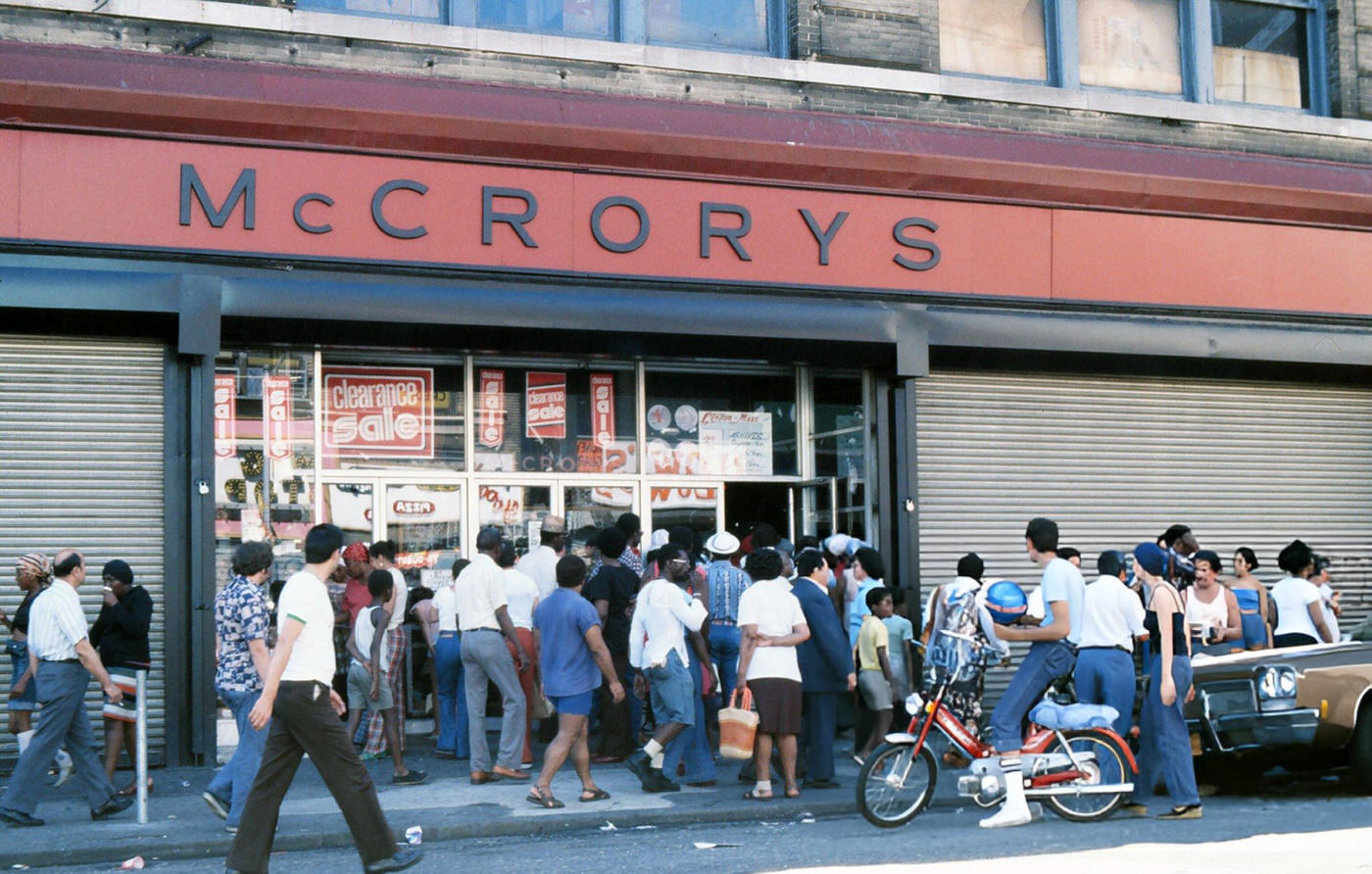

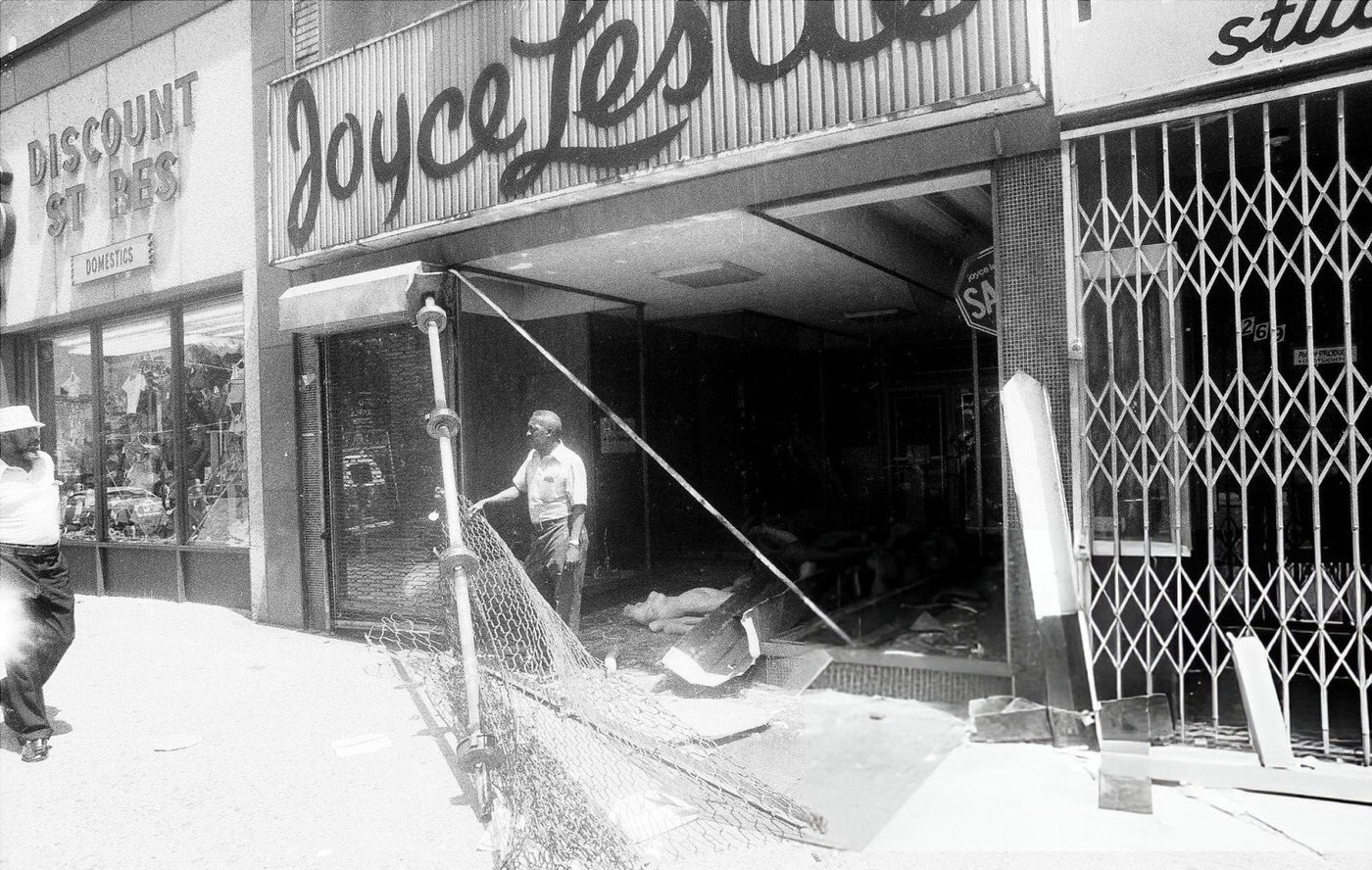

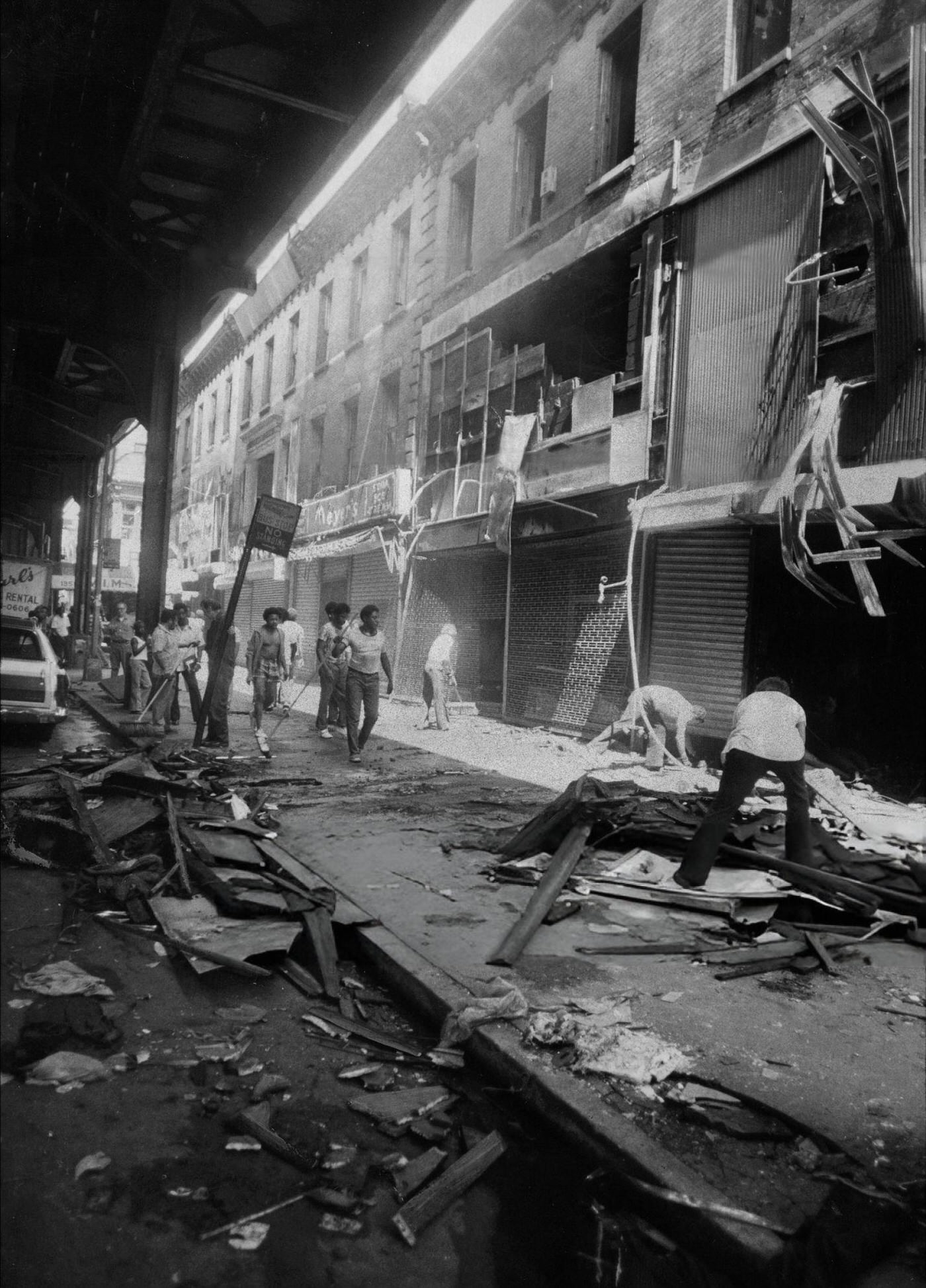

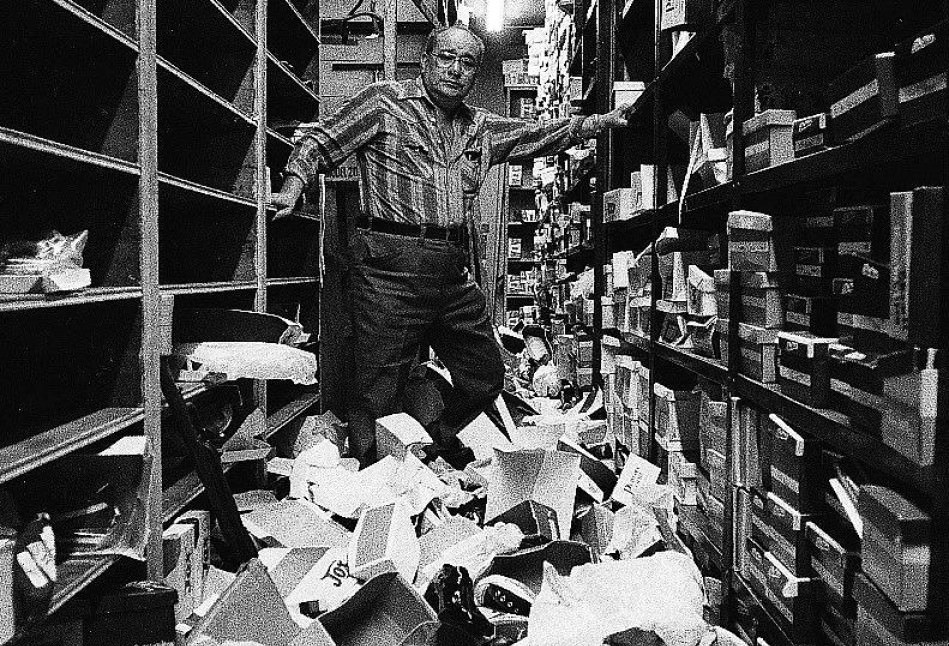

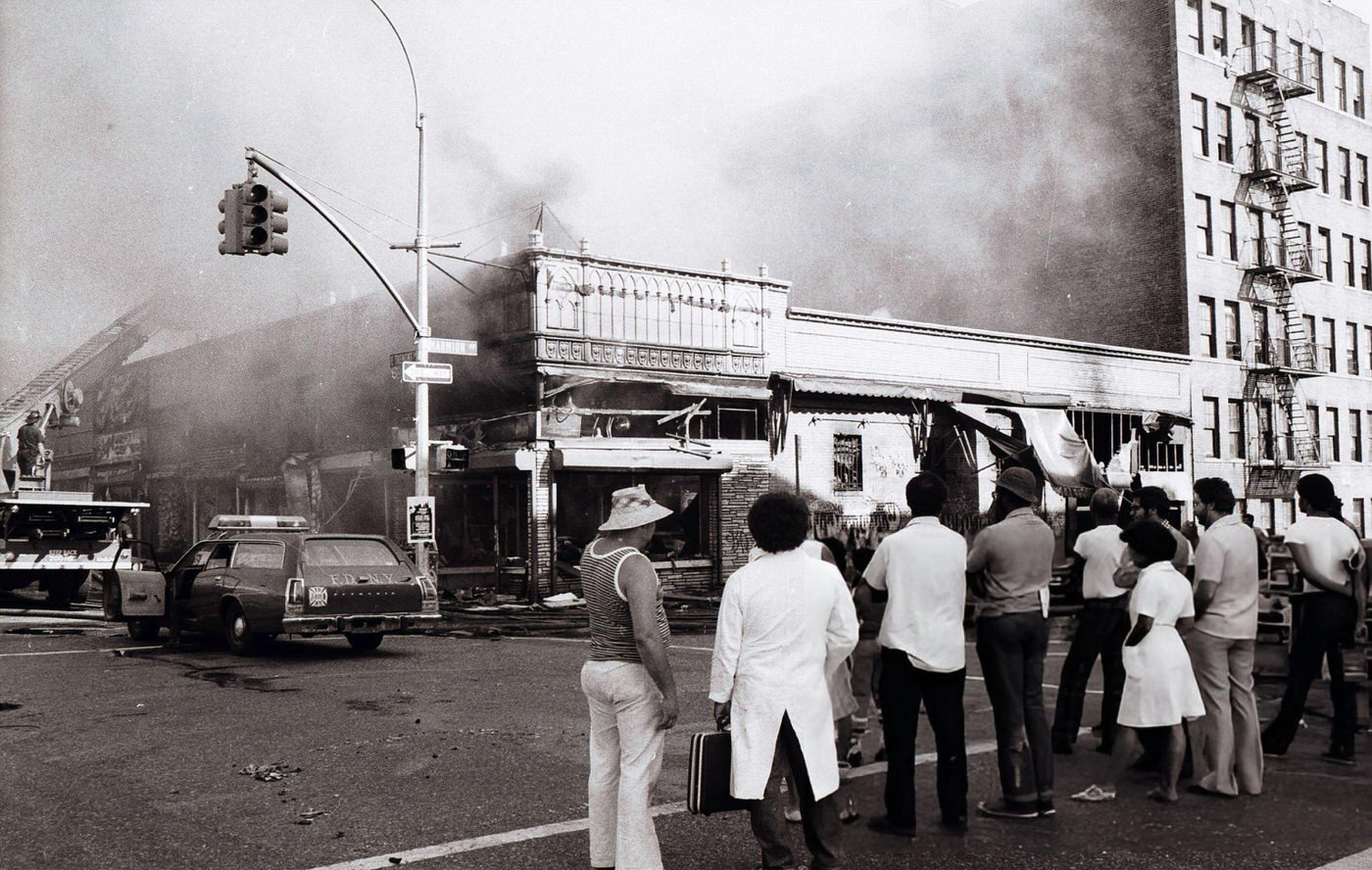

Within minutes of the city going dark, the simmering tensions of the summer exploded into widespread civil disorder. Looting, vandalism, and arson erupted across numerous neighborhoods, particularly affecting poorer communities already strained by the economic crisis. Areas like Bushwick, Bedford-Stuyvesant, and Crown Heights in Brooklyn, along with Harlem in Manhattan and parts of the South Bronx, saw intense activity.

Stores of all kinds were targeted. Vandals smashed windows and, in some cases, used cars with ropes to tear protective metal grates off storefronts. People streamed into broken shops, hauling away anything they could carry—television sets, radios, clothing, jewelry, furniture, appliances, and food. Mannequins were stripped bare on Broadway. Supermarket aisles were emptied, with people filling shopping carts. One Bronx car dealership had 50 new Pontiacs stolen. The darkness provided cover for acts driven by a complex mix of opportunism, desperation, and anger.

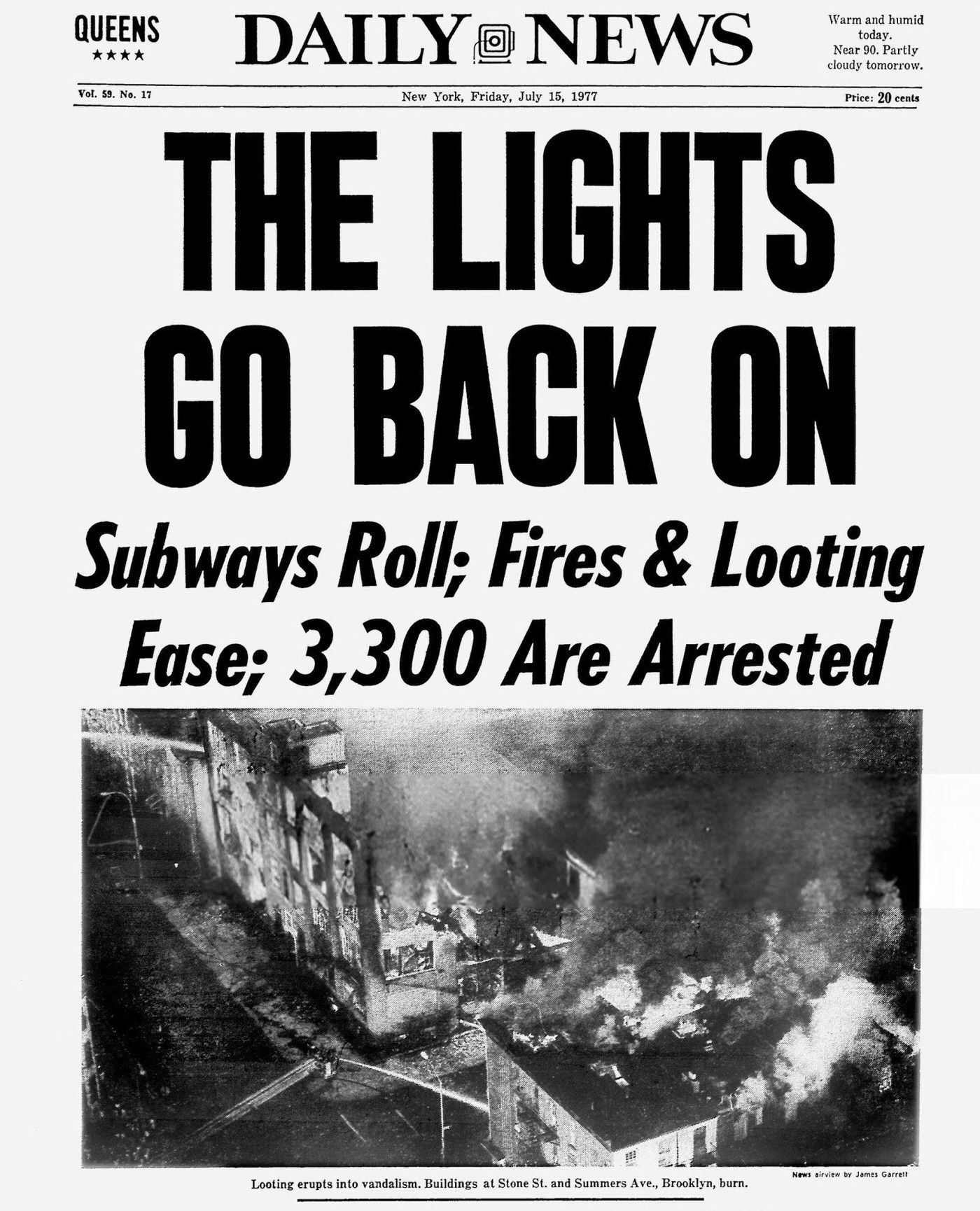

The Scale of the Disorder

The chaos lasted throughout the 25-hour blackout period. Official reports and studies documented the staggering scale of the destruction. Looting and rioting damaged 1,616 stores across 31 distinct neighborhoods. The Fire Department responded to 1,037 fires, including 14 severe multiple-alarm blazes. Arson was rampant in some areas; Bushwick saw about 25 fires still burning the morning after the blackout began. Along a stretch of Broadway separating Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant, roughly 35 blocks were devastated, with 134 stores looted and 45 of those set on fire. A congressional study estimated the total cost of damages at just over $300 million in 1977 dollars.

Responding to the Crisis: Emergency Services Overwhelmed

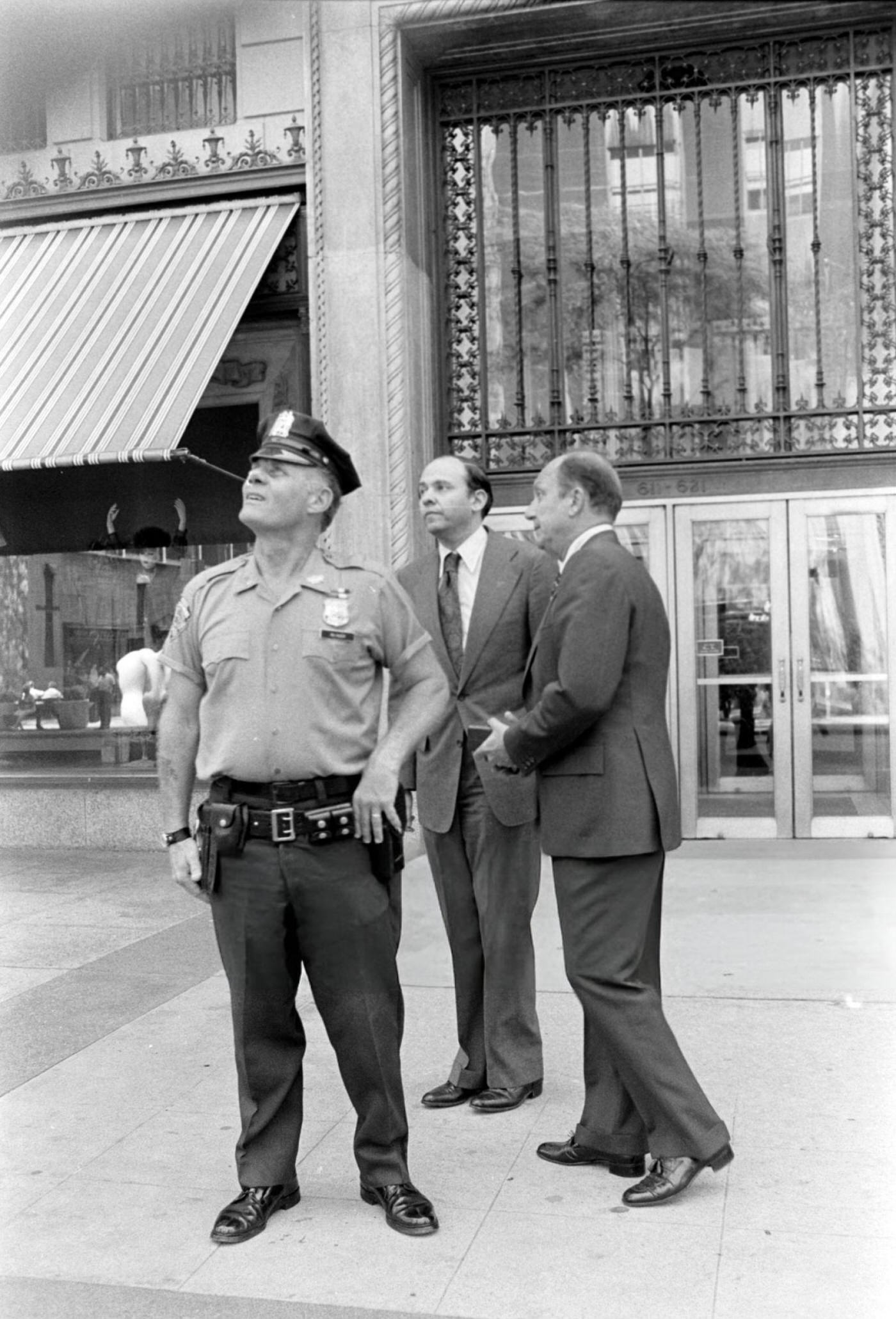

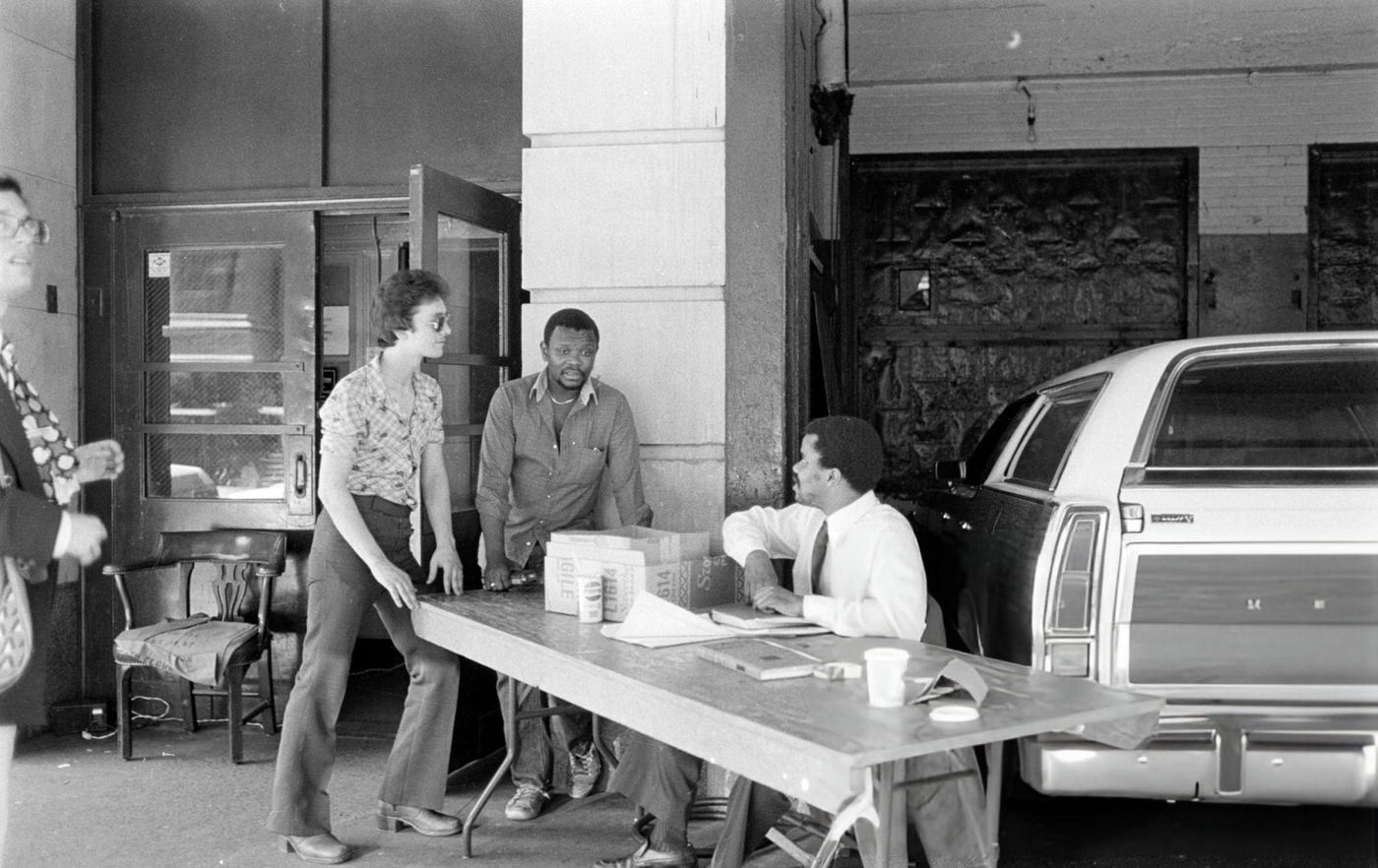

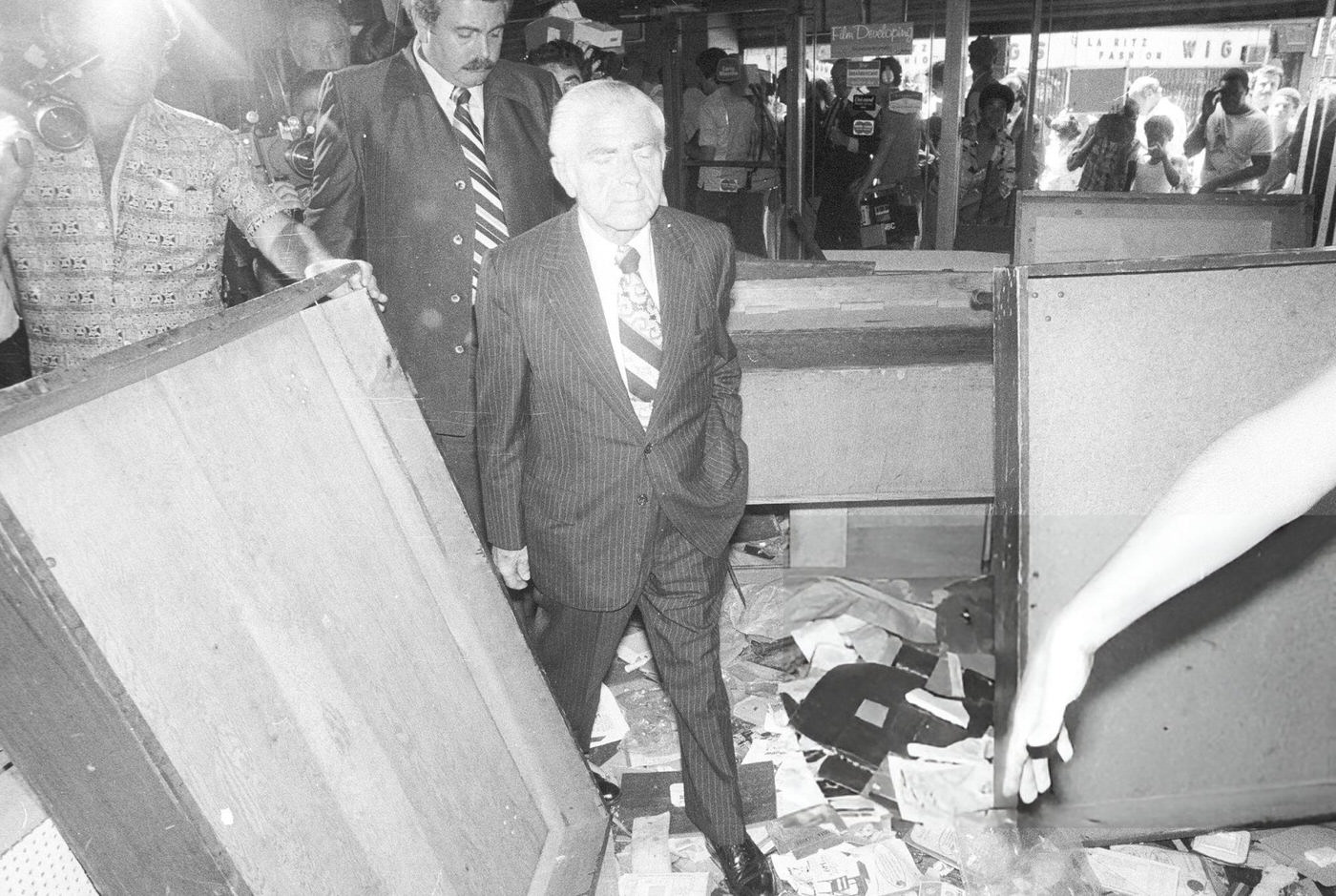

City authorities struggled to cope with the simultaneous power failure and massive outbreak of civil disorder. Mayor Abraham Beame declared a state of emergency and ordered all available police officers and firefighters to report for duty, though many had difficulty reaching their posts due to the transportation shutdown. The New York City Police Department (NYPD) and Fire Department (FDNY) faced immense challenges, operating in darkness often without functioning radio equipment. They were vastly outnumbered by the crowds engaged in looting and arson. Firefighters battled blazes across the city, hampered by false alarms that were double the usual number. Police officers attempted to restore order and make arrests amidst the mayhem. Over the 25 hours, law enforcement made between 3,776 and 4,500 arrests—the largest mass arrest in the city’s history. Holding facilities became so overcrowded that precinct basements and other makeshift areas had to be used. The crisis took a toll on emergency responders, with reports indicating around 550 police officers were injured. Some reports also noted injuries to dozens of firefighters.

Restoring Power: A 25-Hour Ordeal

While chaos gripped parts of the city, Con Edison engineers worked frantically to bring the power system back online. Restoration procedures began around 10:26 PM on July 13, less than an hour after the system collapsed. However, restarting a complex urban power grid from a complete shutdown proved exceptionally difficult. Initial attempts to re-energize major parts of the system failed. Engineers had to adopt a painstaking, sectionalized approach, restoring power to small areas one at a time.

Several technical challenges specific to New York’s infrastructure slowed the process considerably. The city’s extensive network of underground transmission cables, while normally efficient, created excessively high voltage conditions when engineers tried to feed power back into the dormant system from outside sources. This high voltage damaged equipment like transformers and delayed the safe re-energization of lines. Additionally, the pressure needed to maintain the insulation in some critical underground cables was lost during the outage, partly because the pumps themselves relied on the power grid, and partly due to pre-existing leaks. Restoring pressure took time, further delaying the reactivation of key transmission paths.

The first customers to have power restored were in Westchester County, just after midnight on July 14. Within New York City, the Jamaica network in Queens was among the first areas brought back online around 1:44 AM. Restoration proceeded network by network throughout the day and into the evening of July 14. The final network, Yorkville in Manhattan, was restored at 10:39 PM on Thursday, July 14. After approximately 25 hours of darkness and turmoil, full power finally returned to the city.

![[Factually Corrected] A Crowd At The Twa Terminal At Kennedy Airport In Queens, New York During The Blackout, 1977.](https://seeoldnyc.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/New_York_City_1977_Blackout_10.jpg)

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings