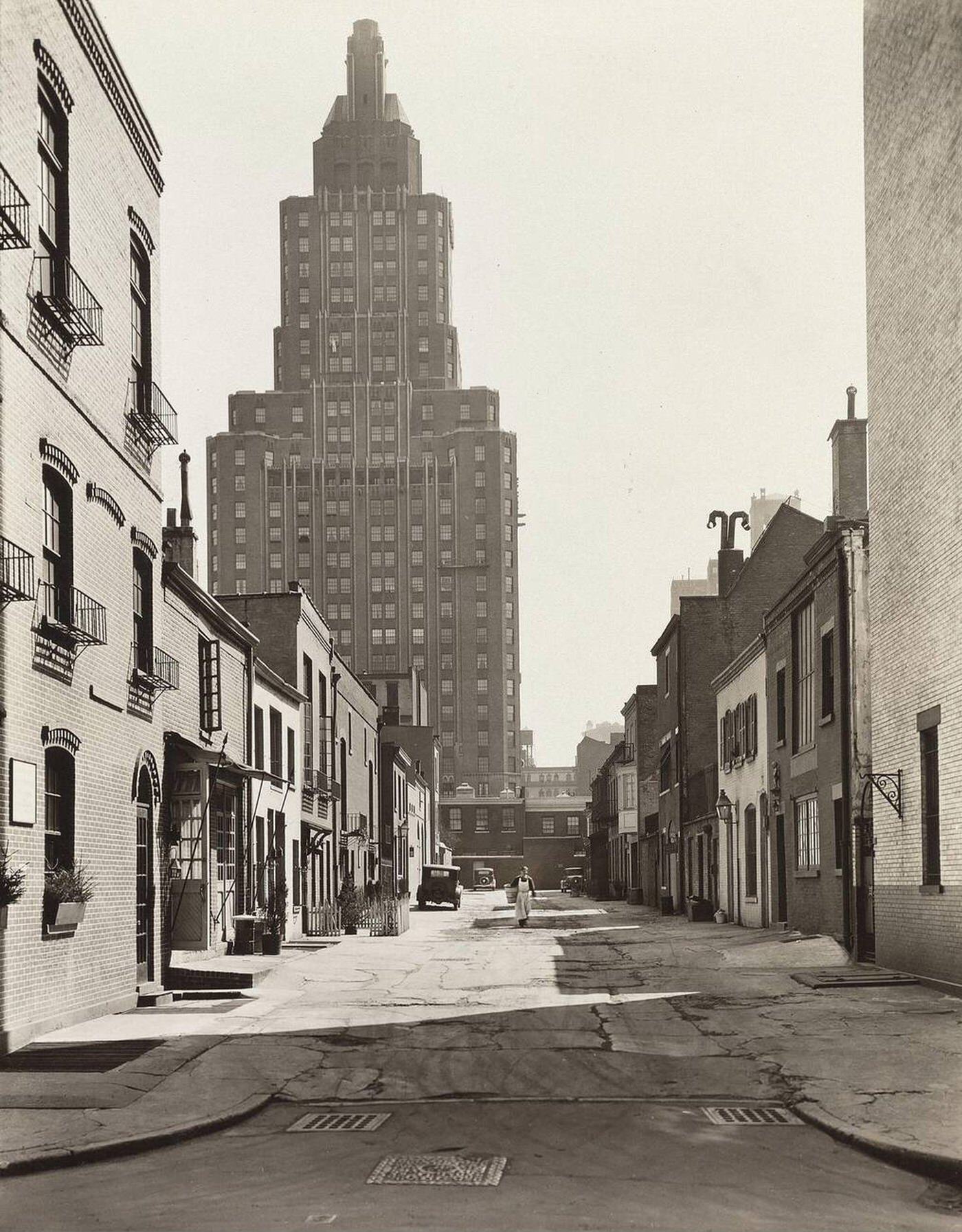

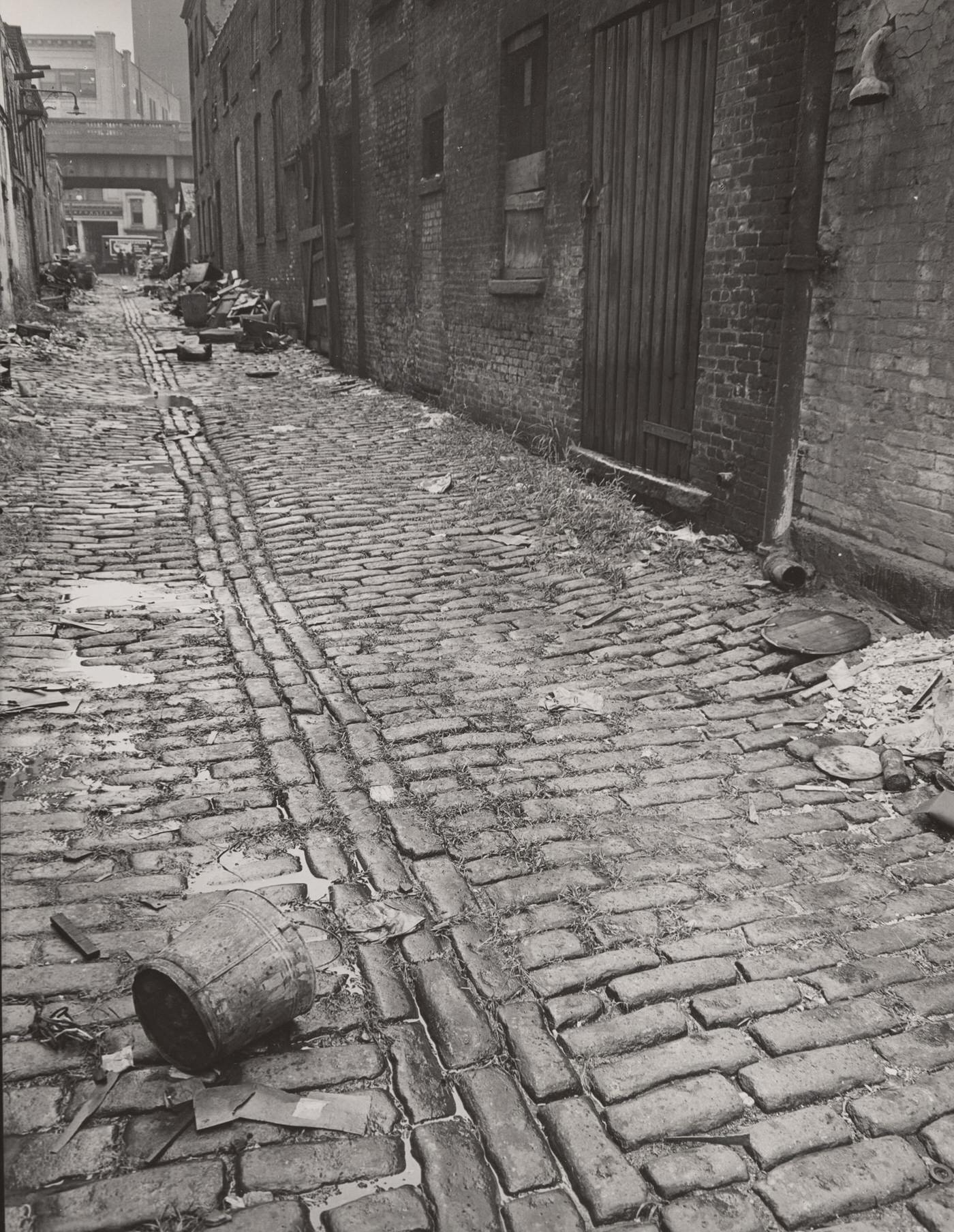

Greenwich Village in the 1930s was a neighborhood shaped by the Great Depression and its long-standing identity as a haven for artists, writers, and thinkers. The economic hardship of the era reinforced the Village’s reputation for affordable living, attracting those who sought a creative life on a limited budget. Its winding streets, brick townhouses, and low-rise tenements stood in contrast to the soaring skyscrapers being built farther uptown.

The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 formally changed the neighborhood’s social landscape. Speakeasies that had operated in secret throughout the 1920s became legitimate bars and restaurants. These establishments, many of them small and intimate, served as gathering places for conversation and debate among the area’s residents.

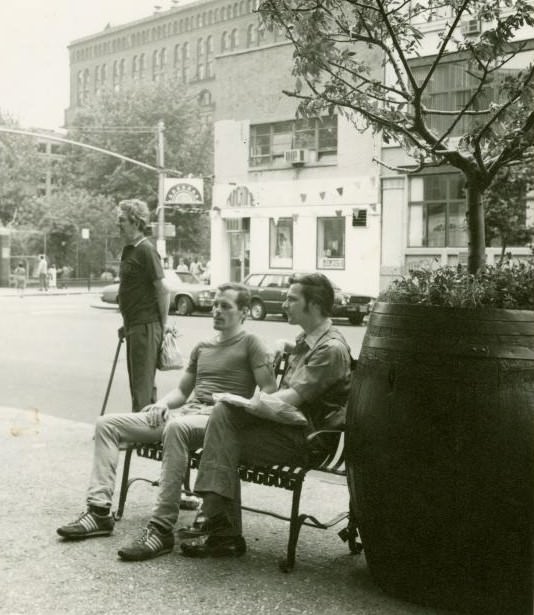

Washington Square Park was the true heart of the Village. On any given day, the park was a cross-section of the community. Unemployed workers sat on benches, artists sketched at their easels, and local residents strolled beneath the Washington Arch. The park served as a public stage for folk singers, poets, and political orators who took advantage of the open space to share their work and ideas.

Read more

The Federal Art Project, part of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration (WPA), had a visible presence in the neighborhood. The program employed hundreds of artists, many of whom lived in the Village. It funded the creation of public murals in schools and post offices and supported painters and sculptors, allowing them to continue their work despite the economic collapse. This government support helped sustain the creative energy of the community.

Nightlife in the Village offered unique alternatives to the glitzy supper clubs uptown. In 1938, Cafe Society opened on Sheridan Square with the specific purpose of being a racially integrated nightclub. It showcased legendary jazz and blues musicians like Billie Holiday, creating a progressive social space that welcomed both black and white patrons. The area’s theaters, such as the Provincetown Playhouse, continued to stage experimental and politically charged plays.

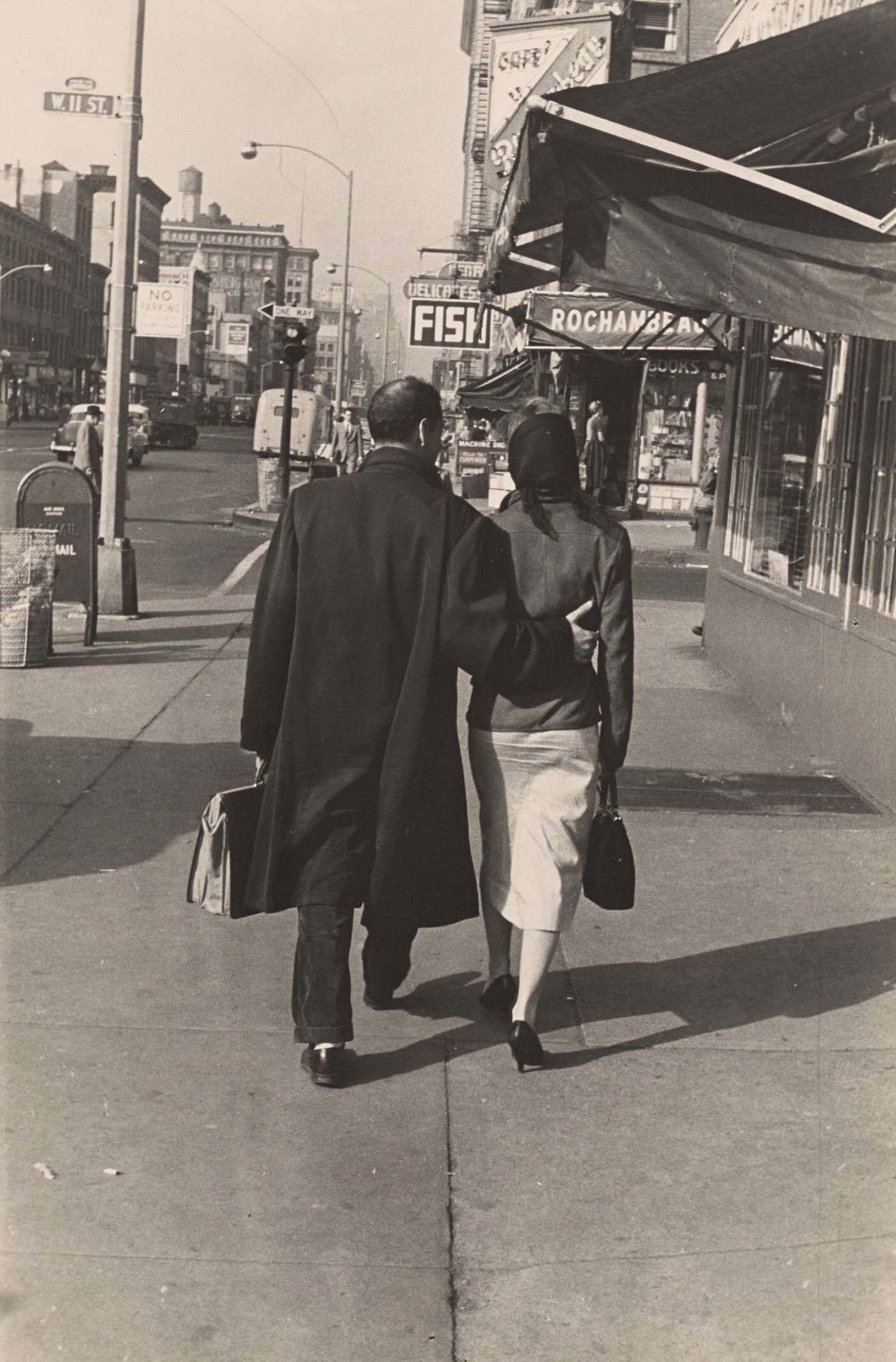

Despite its bohemian reputation, the Village was also a neighborhood of working-class families, particularly Italian-American families in the South Village. These residents maintained strong community traditions, with local bakeries, butcher shops, and social clubs serving their needs. The streets were active with pushcart vendors selling fruits and vegetables, adding to the lively, village-like atmosphere.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings