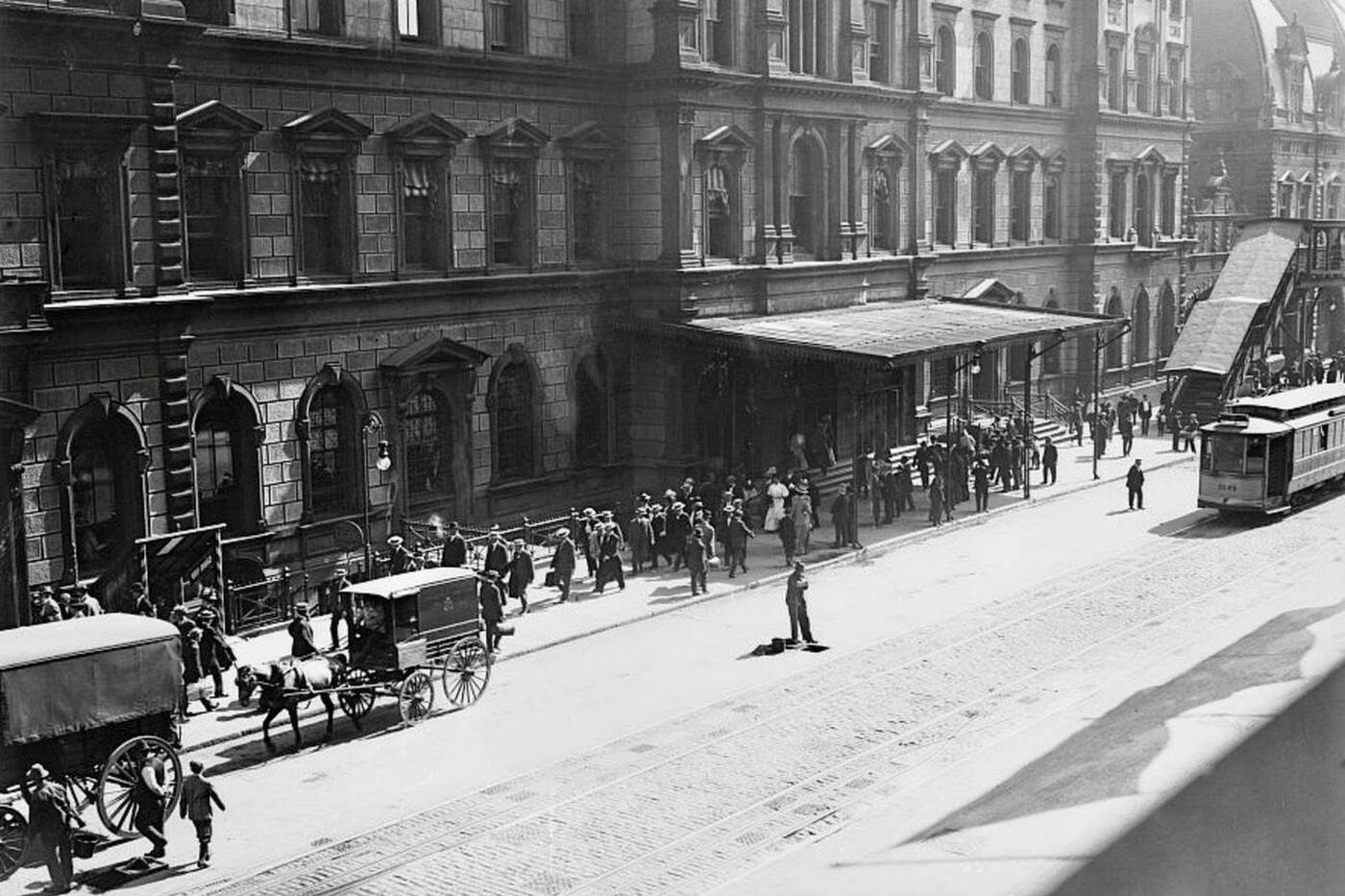

At the dawn of the 20th century, the existing Grand Central Station was a cramped and dangerous place. Smoke and steam from locomotives filled the train shed and the Park Avenue tunnel, leading to a deadly train collision in 1902. The disaster made it clear that a radical change was necessary. The New York Central Railroad embarked on one of the most ambitious engineering projects of the era: to demolish the old station, electrify the train lines, and sink all the tracks and train yards beneath the streets of Manhattan.

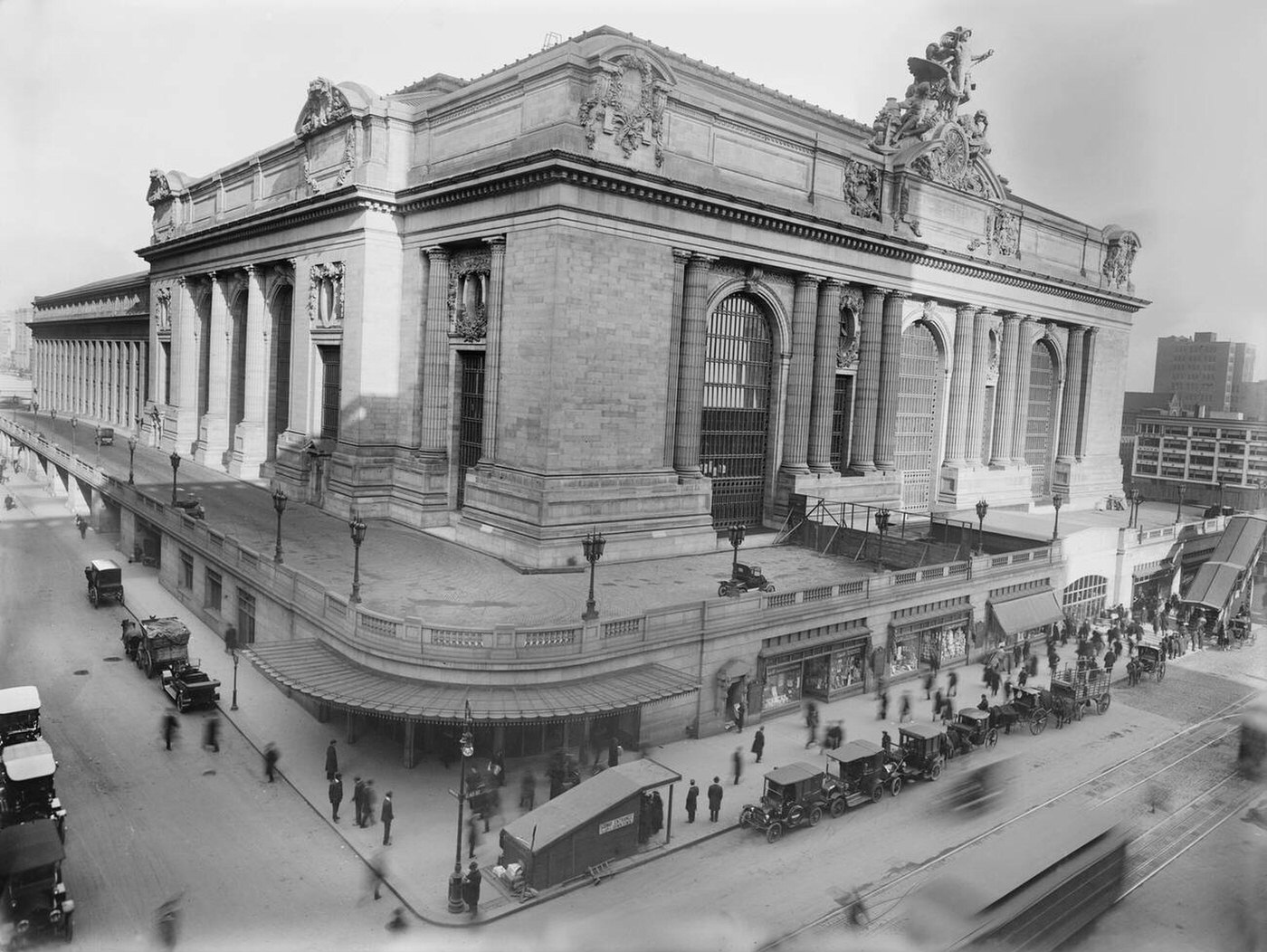

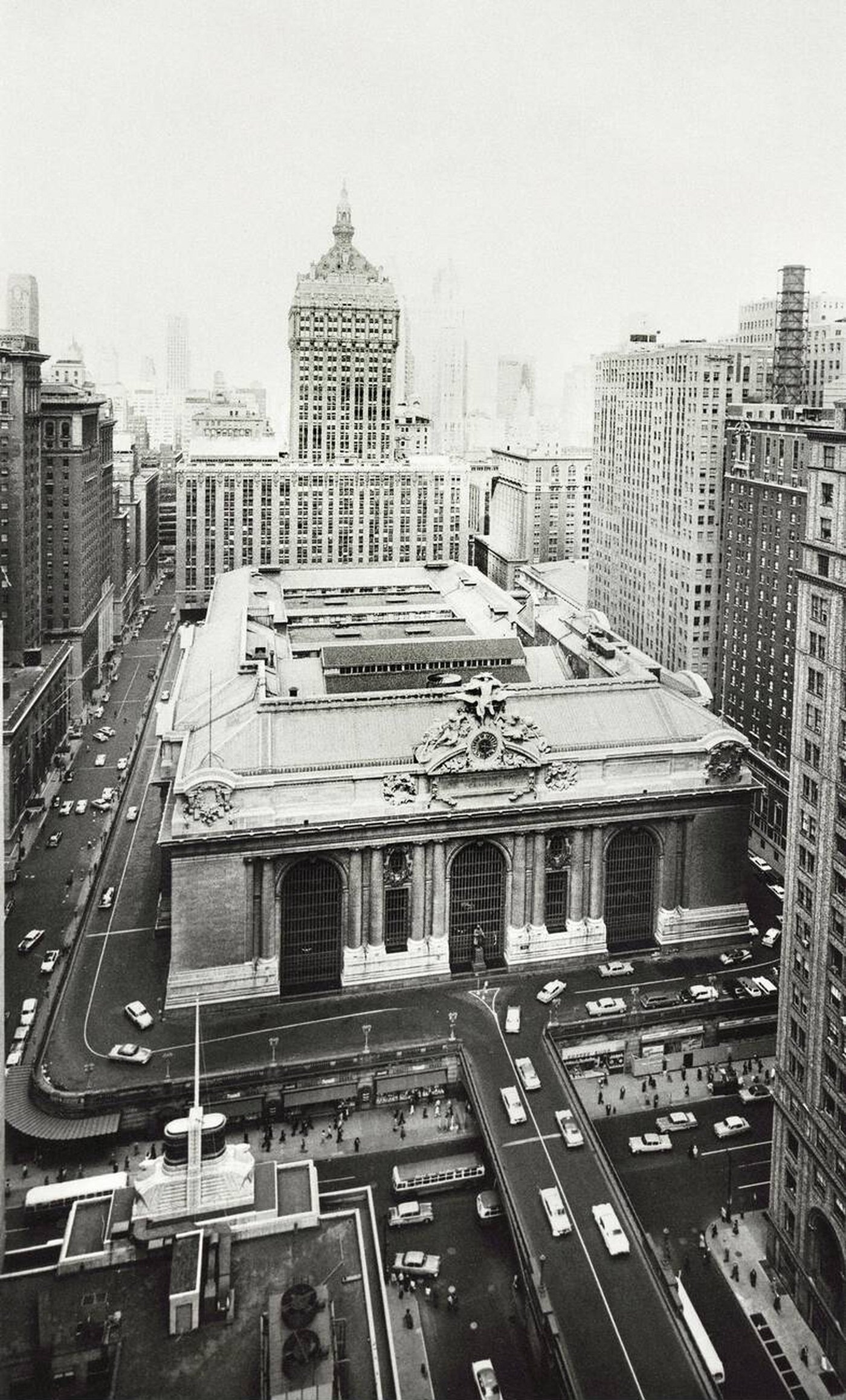

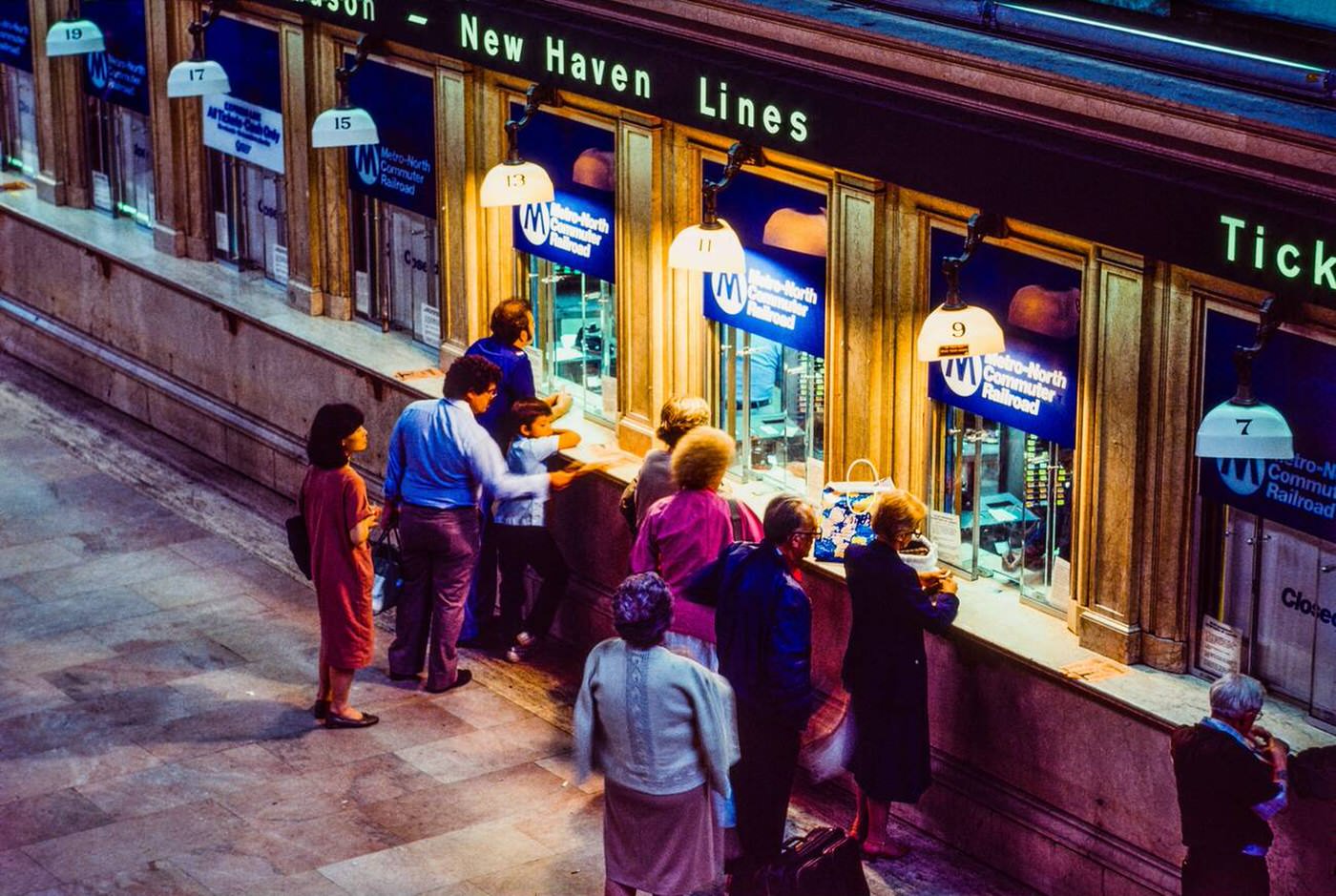

For a decade, a massive open pit stretched across several city blocks, a site often called the “Grand Canyon of Park Avenue.” While this enormous excavation and construction project was underway, hundreds of trains continued to operate daily. The new, two-level station design was revolutionary, with an upper level for long-distance express trains and a lower level for suburban commuter trains. When Grand Central Terminal officially opened on February 2, 1913, it was celebrated as a modern marvel of design and efficiency.

The Golden Age: 1910s-1940s

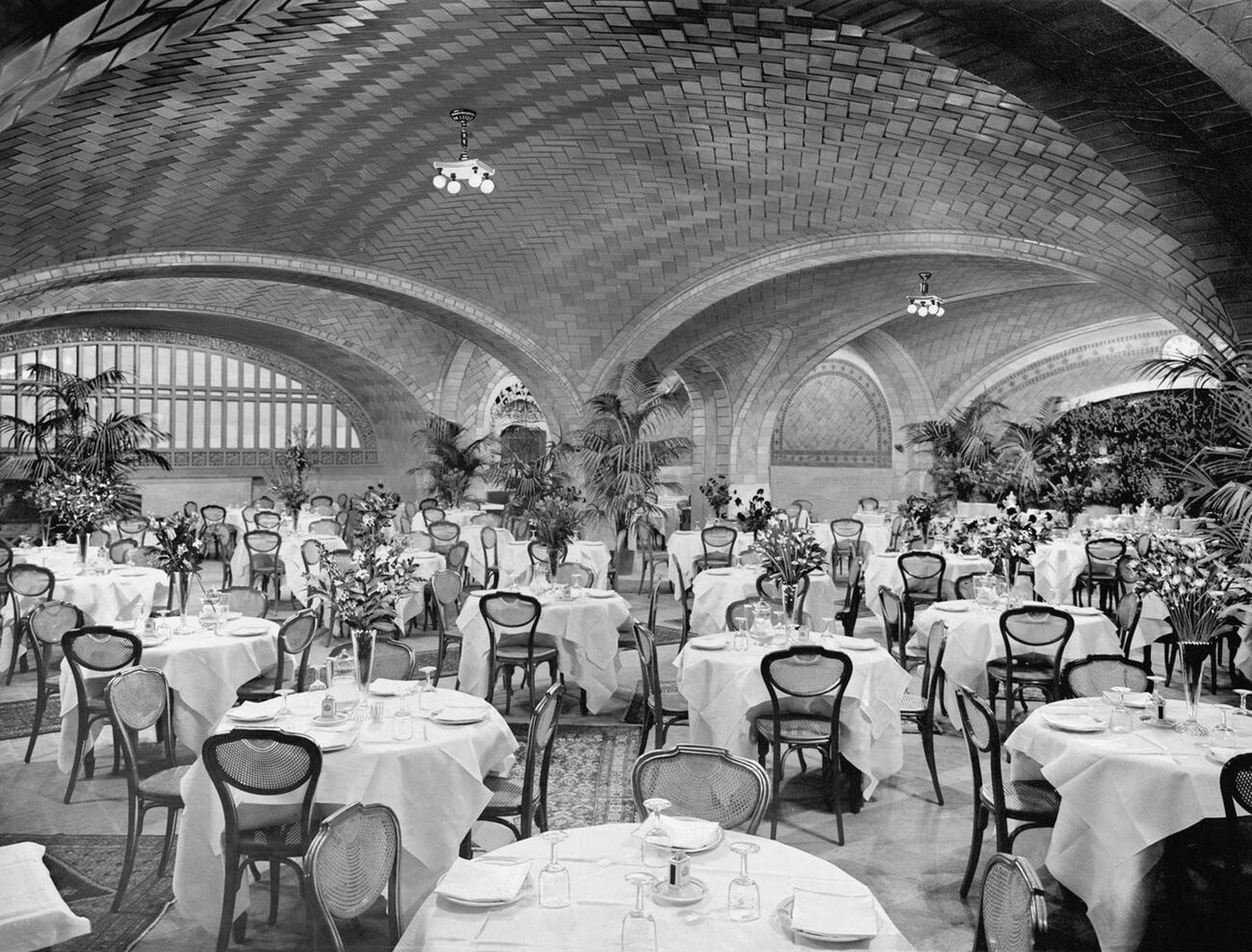

The new Terminal was far more than just a place to catch a train; it was a self-contained city. Inside its walls, travelers found high-end shops, restaurants, waiting rooms, an art gallery, and even a newsreel movie theater. The famous Oyster Bar & Restaurant opened with the Terminal in 1913 on the lower level and quickly became a New York institution.

Read more

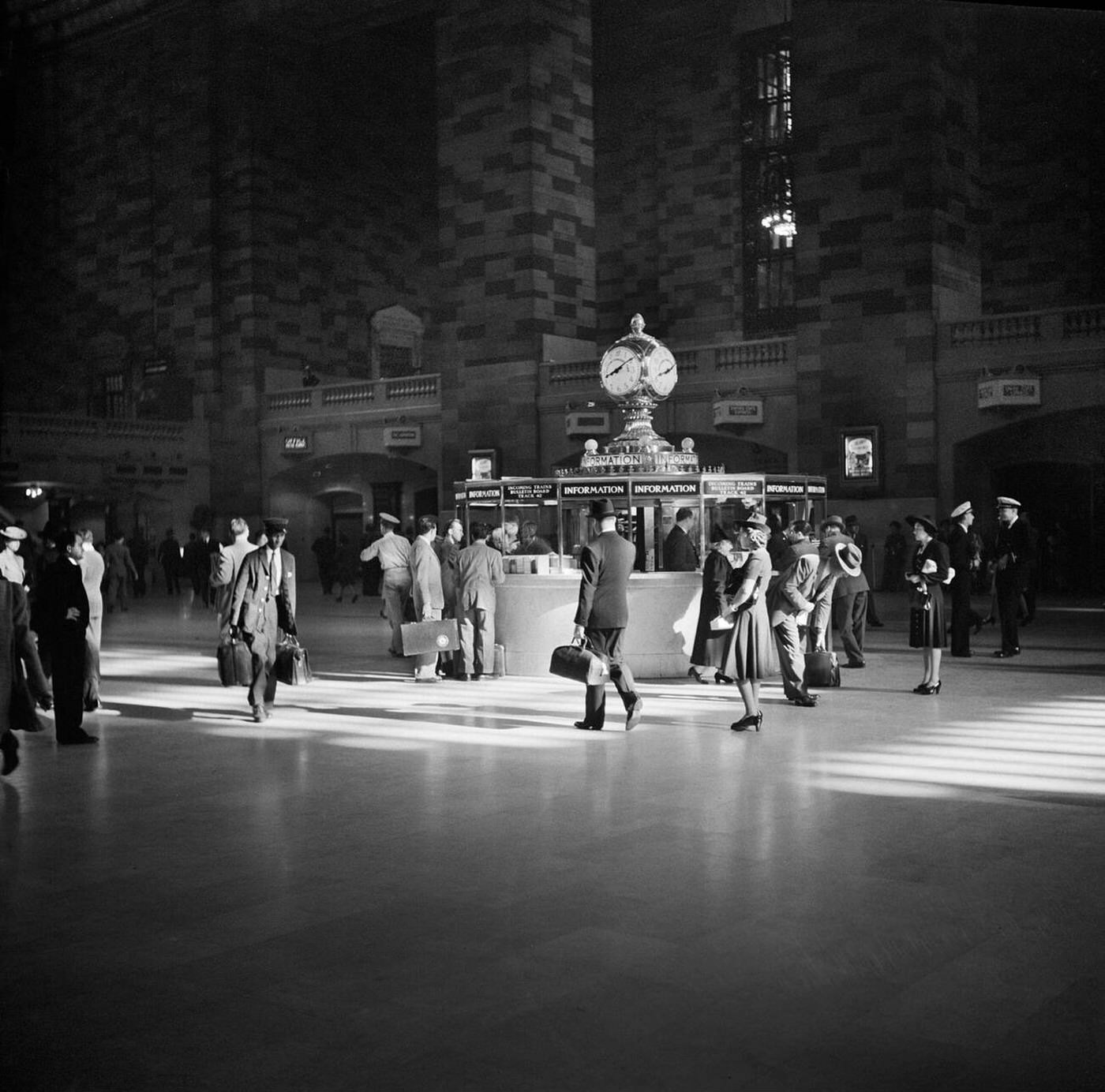

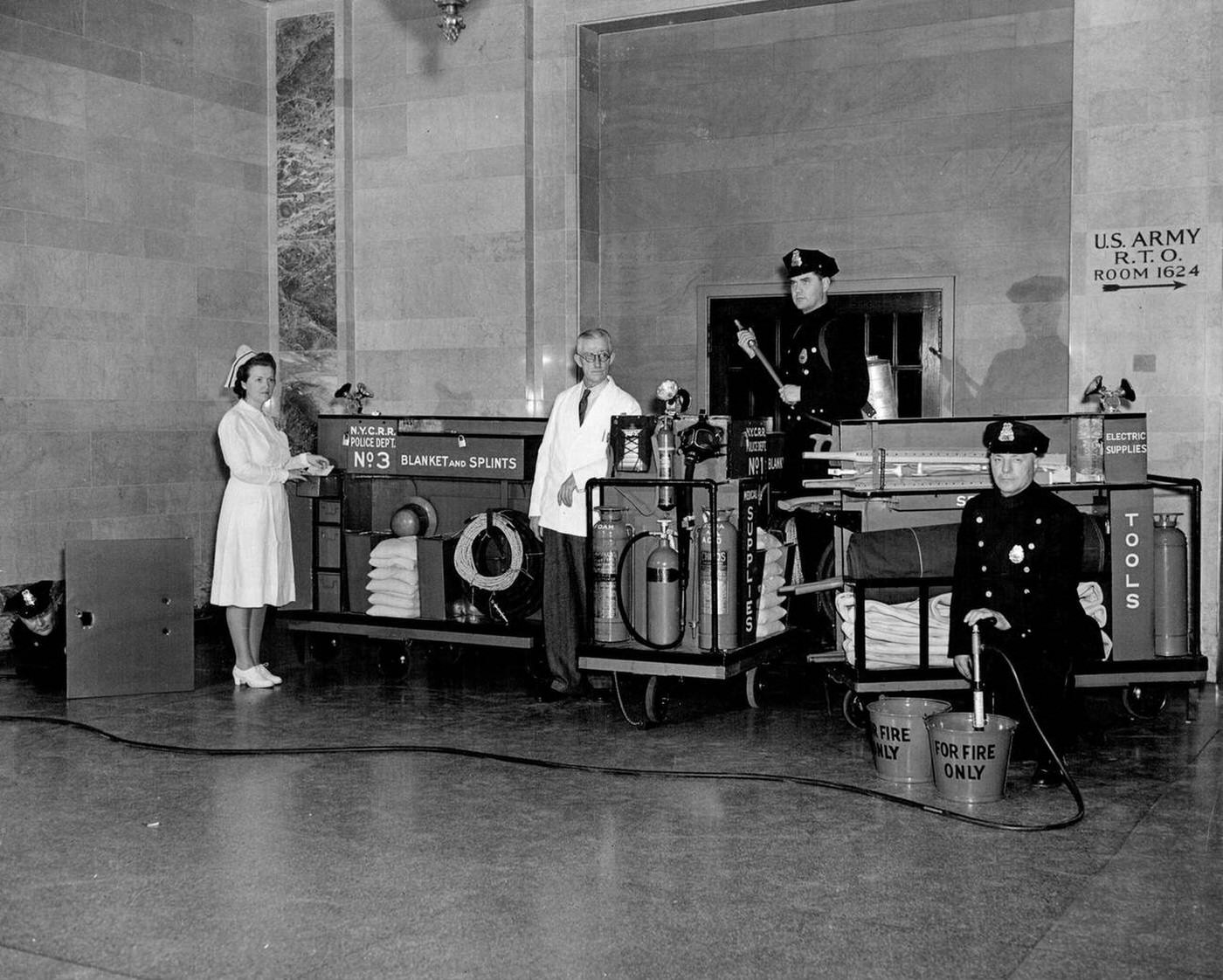

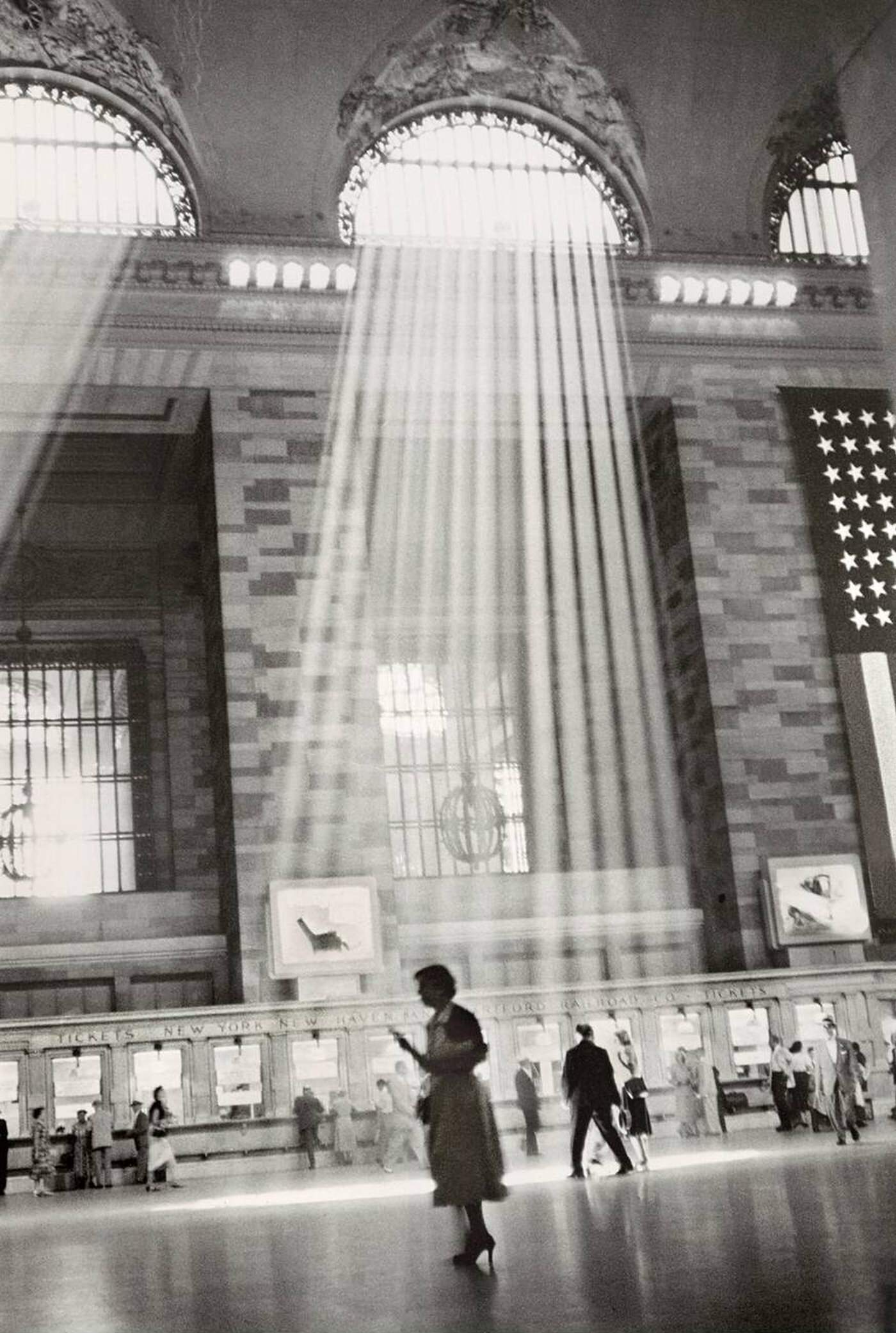

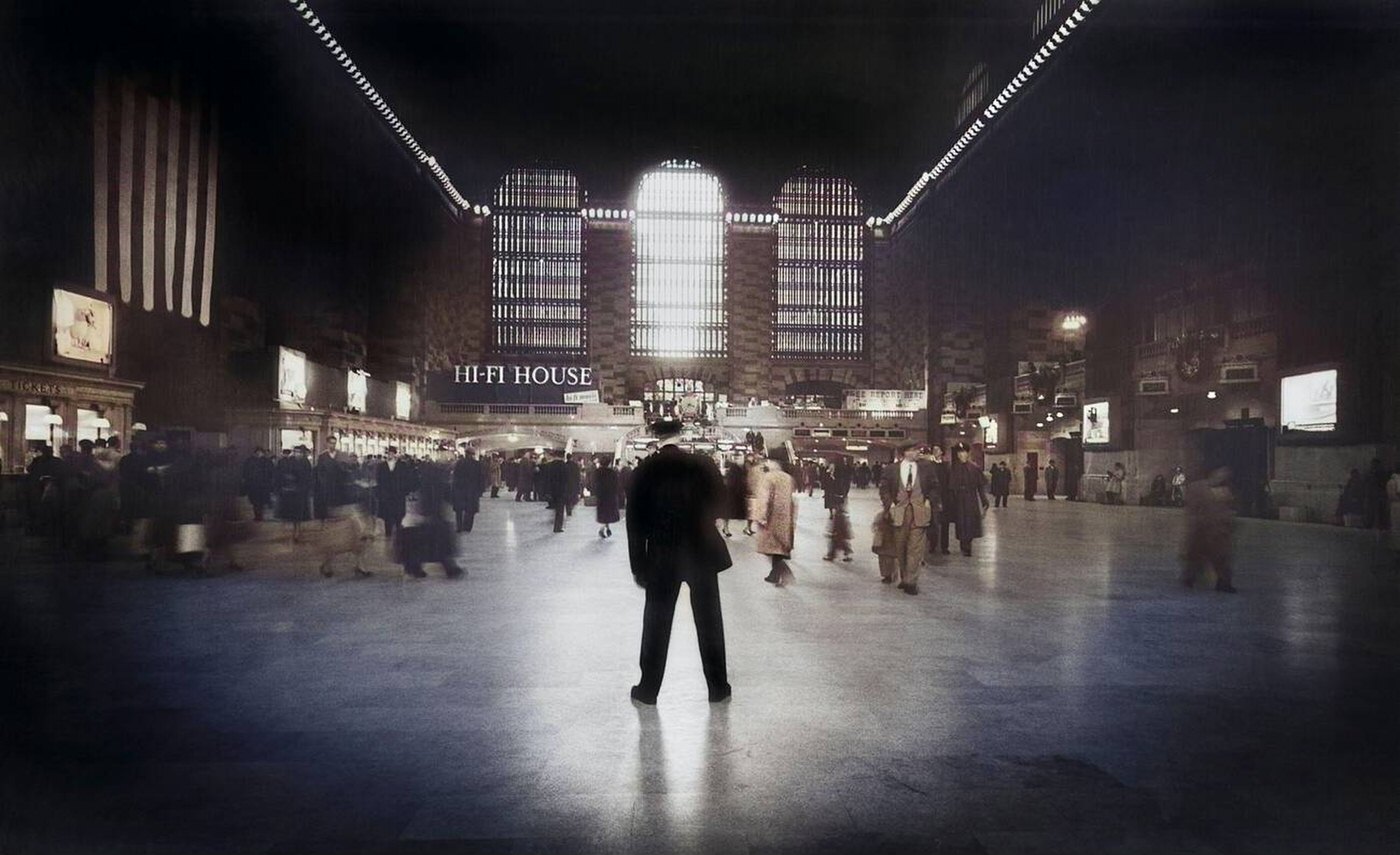

The Main Concourse was the heart of the building. Its vast, 125-foot-high barrel-vaulted ceiling was covered with a celestial mural of the zodiac constellations. At its center stood the iconic four-faced clock atop the main information booth, its opal faces glowing. This clock became the designated meeting spot for generations of New Yorkers. Grand Central was the starting point for America’s most famous long-distance trains. Passengers walked a red carpet to board the luxurious *20th Century Limited*, which offered a high-speed, 16-hour journey to Chicago. During World War II, the Terminal’s windows were blacked out as it became a vital, secret hub for moving troops across the country.

Decline and an Uncertain Future: 1950s-1960s

Following World War II, the fortunes of American railroads began to decline. The growing popularity of air travel and the interstate highway system drastically reduced the number of long-distance train passengers. The New York Central Railroad, the owner of Grand Central, started losing money, and the Terminal began to show signs of neglect. The magnificent sky ceiling became obscured by decades of grime and tobacco smoke.

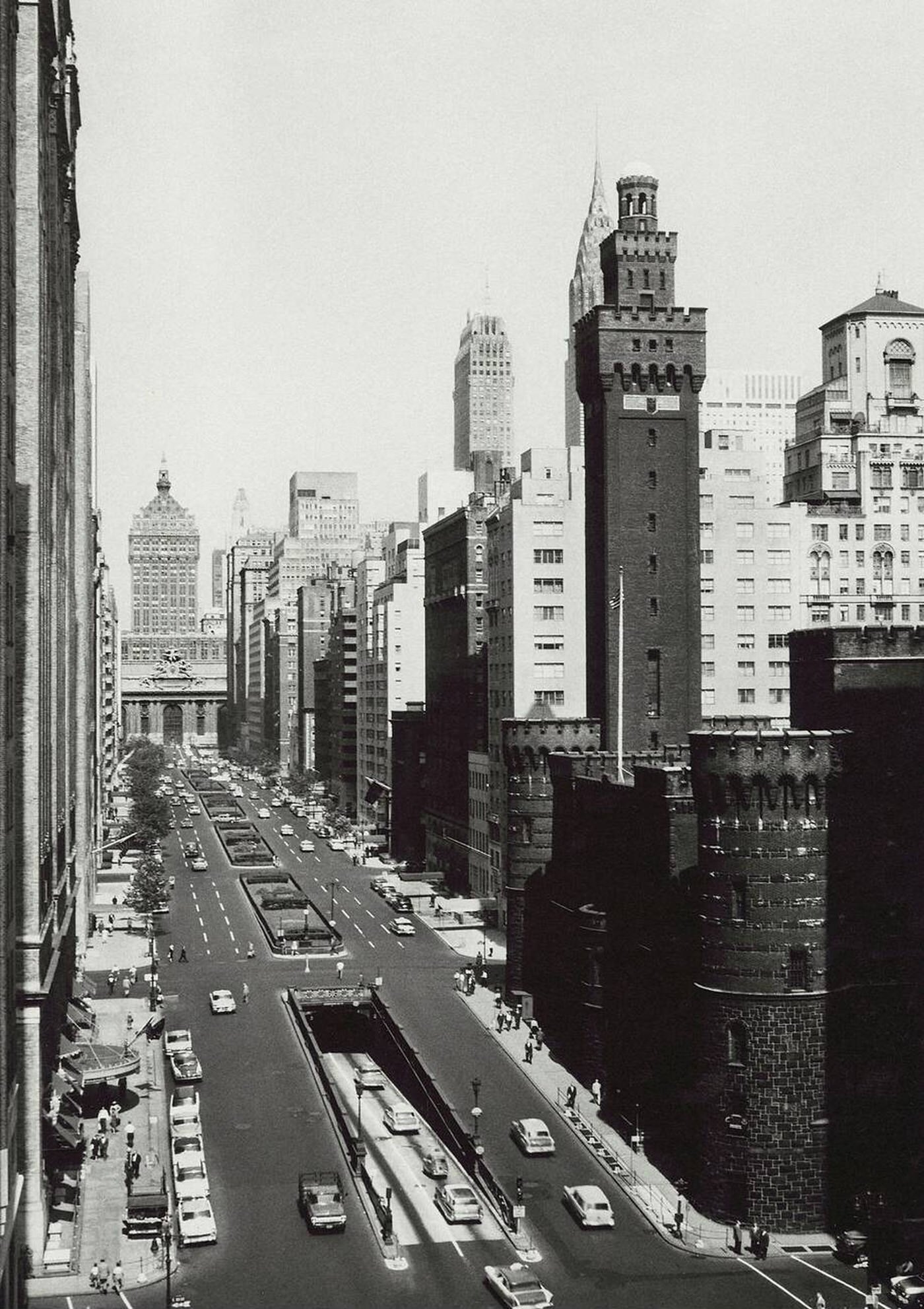

To increase revenue, the railroad made changes that compromised the building’s architectural integrity. A giant, backlit Kodak photograph advertisement, the “Colorama,” was installed across the east balcony of the Main Concourse in 1950. In the mid-1950s, the railroad proposed tearing the Terminal down entirely for a new skyscraper. While that plan failed, it led to the construction of the 59-story Pan Am Building (now the MetLife Building) directly behind the Terminal. Opening in 1963, the massive office tower loomed over the historic structure, casting a literal and figurative shadow over its future.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings