On the bright, sunny morning of Wednesday, June 15, 1904, the paddle-wheel steamboat PS General Slocum left a pier on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. On board were over 1,300 members of St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, mostly German immigrant women and their children. They were dressed in their Sunday best for their 17th annual church picnic, a highly anticipated trip up the East River to a grove on Long Island Sound.

The ship, a large wooden vessel built for excursions, steamed north. As it passed by East 90th Street, smoke was first spotted coming from a forward cabin. This room, known as the Lamp Room, was used for storage and was filled with highly flammable materials, including straw, oily rags, and lamp oil. A fire had started, and it began to spread with incredible speed.

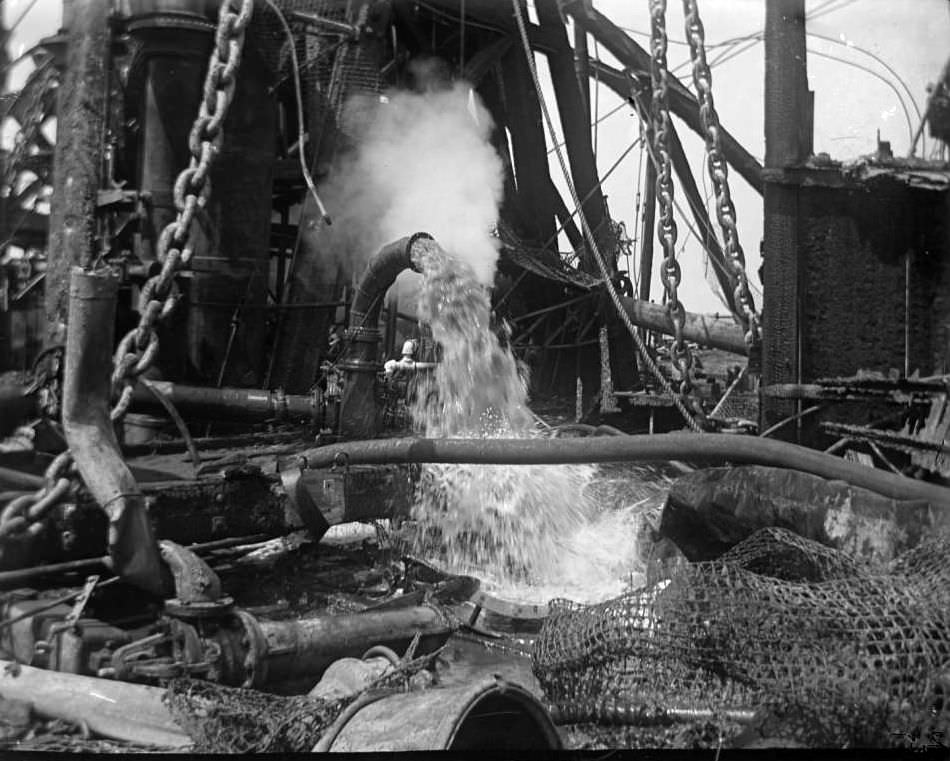

The ship’s crew was slow to react and poorly trained. When they finally attempted to use the fire hoses, the canvas material was so rotted from age that it broke apart under the water pressure. The blaze, fed by the ship’s wooden construction and a recent coat of flammable paint, quickly became an uncontrollable inferno. A strong wind from the south fanned the flames, pushing the fire toward the stern where most of the passengers were gathered.

Read more

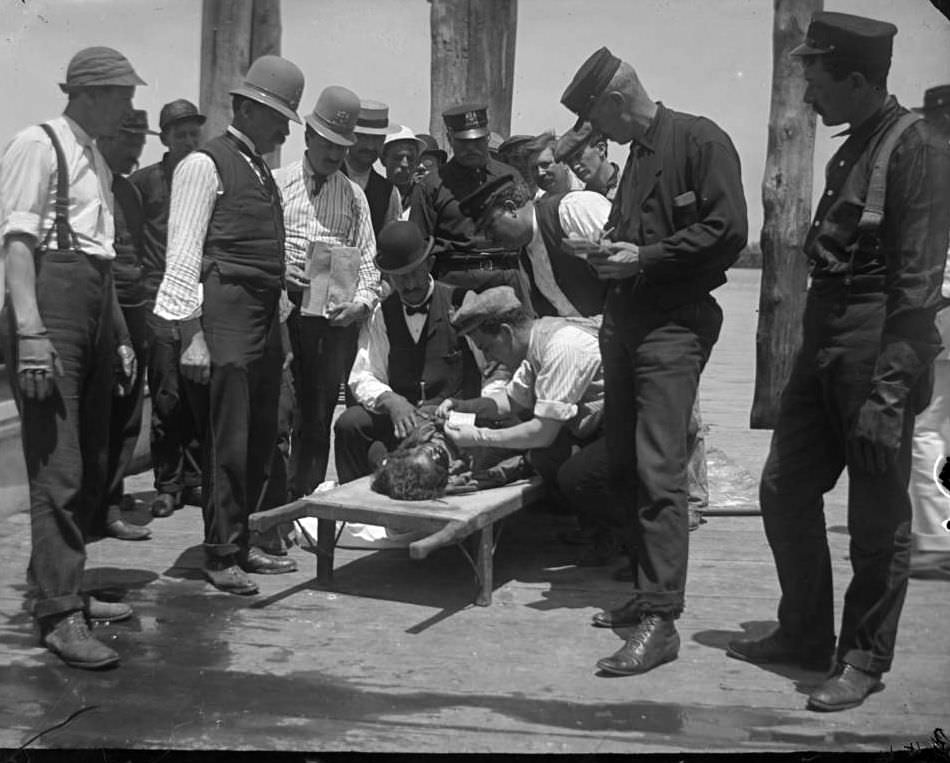

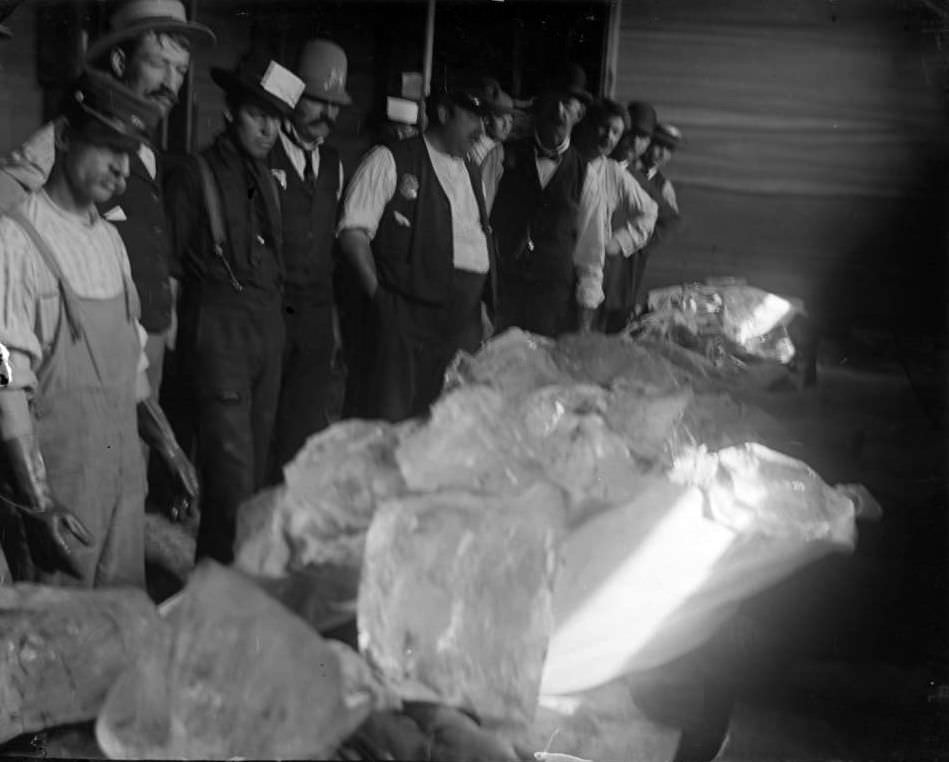

Panic erupted on the decks. Mothers and children, desperate to escape the intense heat and flames, rushed for the life preservers. The preservers, however, were just as useless as the fire hoses. They had been filled with cheap, granulated cork dust that had turned to useless powder over the years. The canvas covers had been painted and repainted, making them stiff and brittle. To meet weight requirements, iron bars had been placed inside many of them. When passengers put on the preservers and jumped into the river, the devices absorbed water, became waterlogged, and dragged them under.

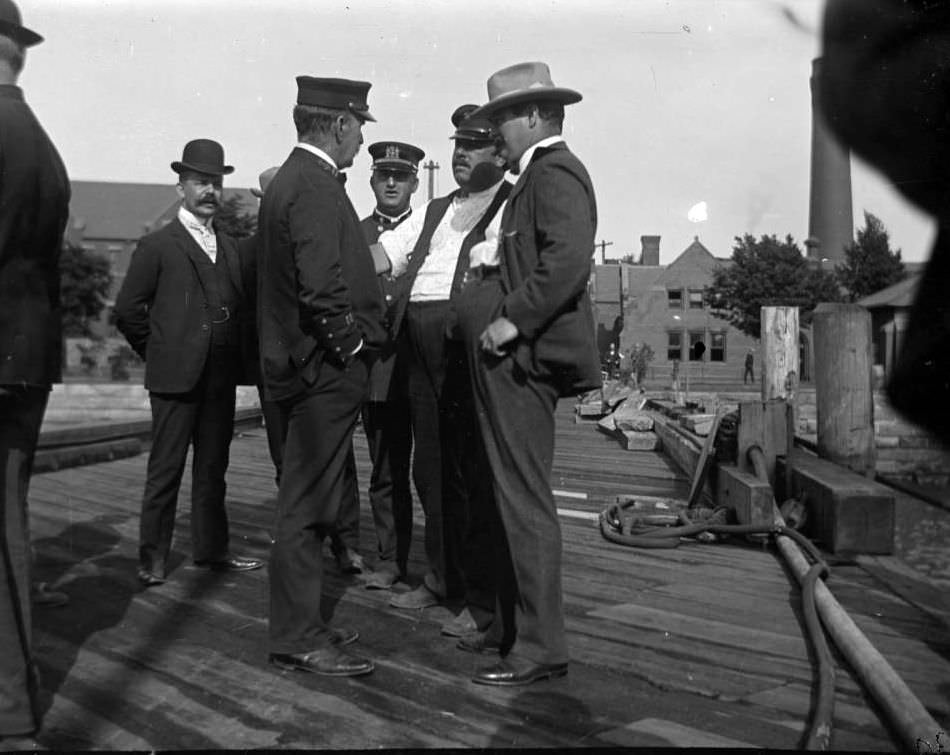

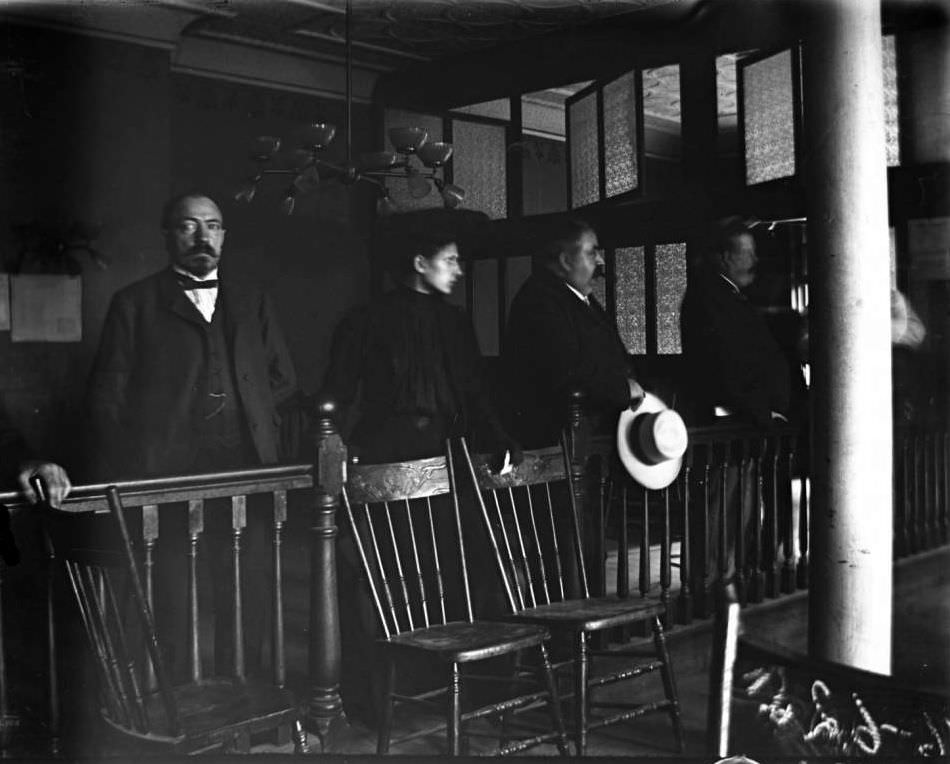

The ship’s captain, William Van Schaick, made a fateful decision. Instead of immediately running the ship ashore on the nearby banks of Manhattan or the Bronx, he chose to continue steaming forward at full speed into the wind. His stated reason was to avoid spreading the fire to waterfront buildings. This action, however, acted like a bellows, dramatically intensifying the fire and turning the ship into a floating furnace.

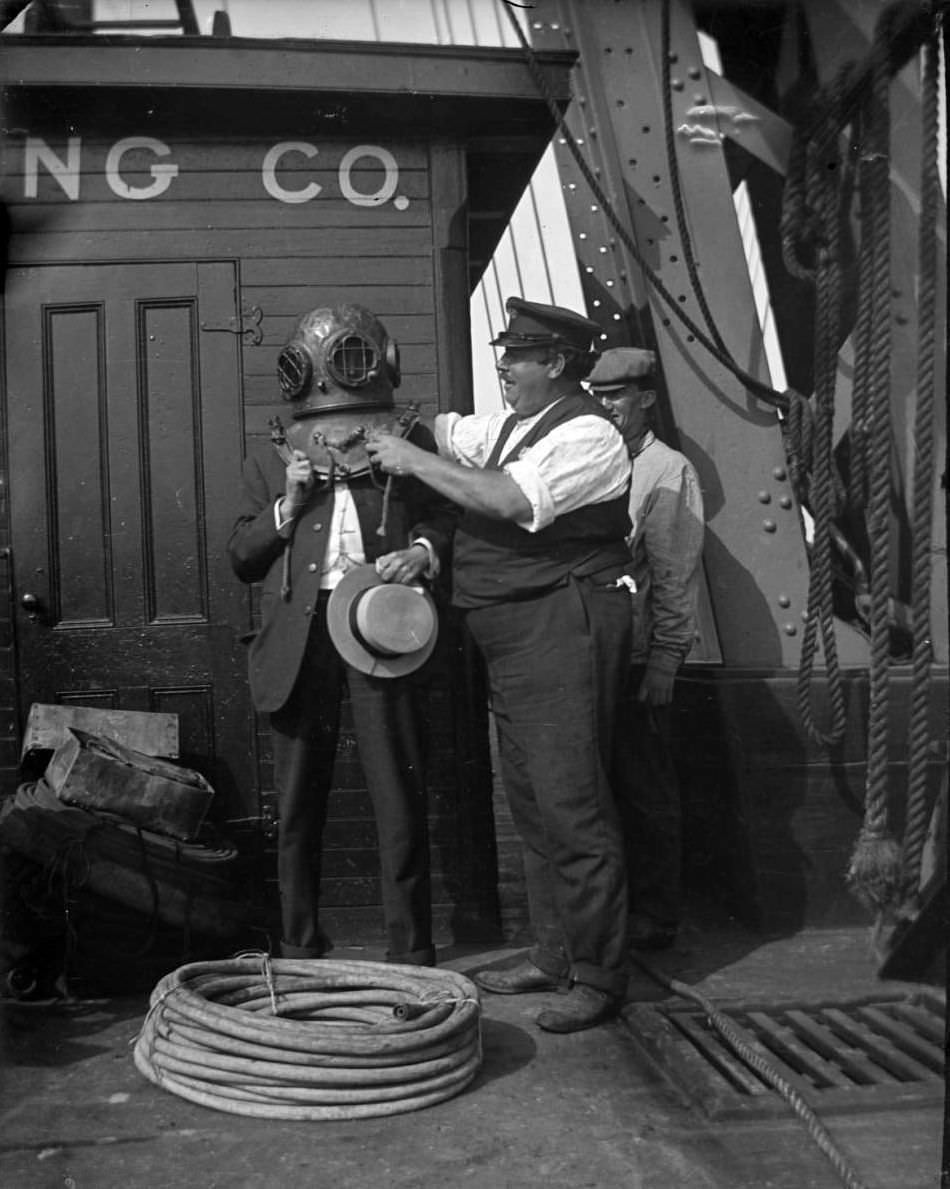

By the time the General Slocum reached the waters near North Brother Island, off the coast of the South Bronx, it was completely engulfed in flames. The captain finally beached the burning wreck on the island’s shore. The scene was one of chaos and horror. The superheated decks collapsed, sending hundreds of people into the fiery hull. Others who jumped or were pushed into the water drowned in the strong currents of the East River, weighed down by their heavy wool clothing and the faulty life preservers. Over 1,021 of the 1,342 people on board died from the fire or by drowning. It was the deadliest single disaster in New York City’s history until the attacks of September 11, 2001.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings