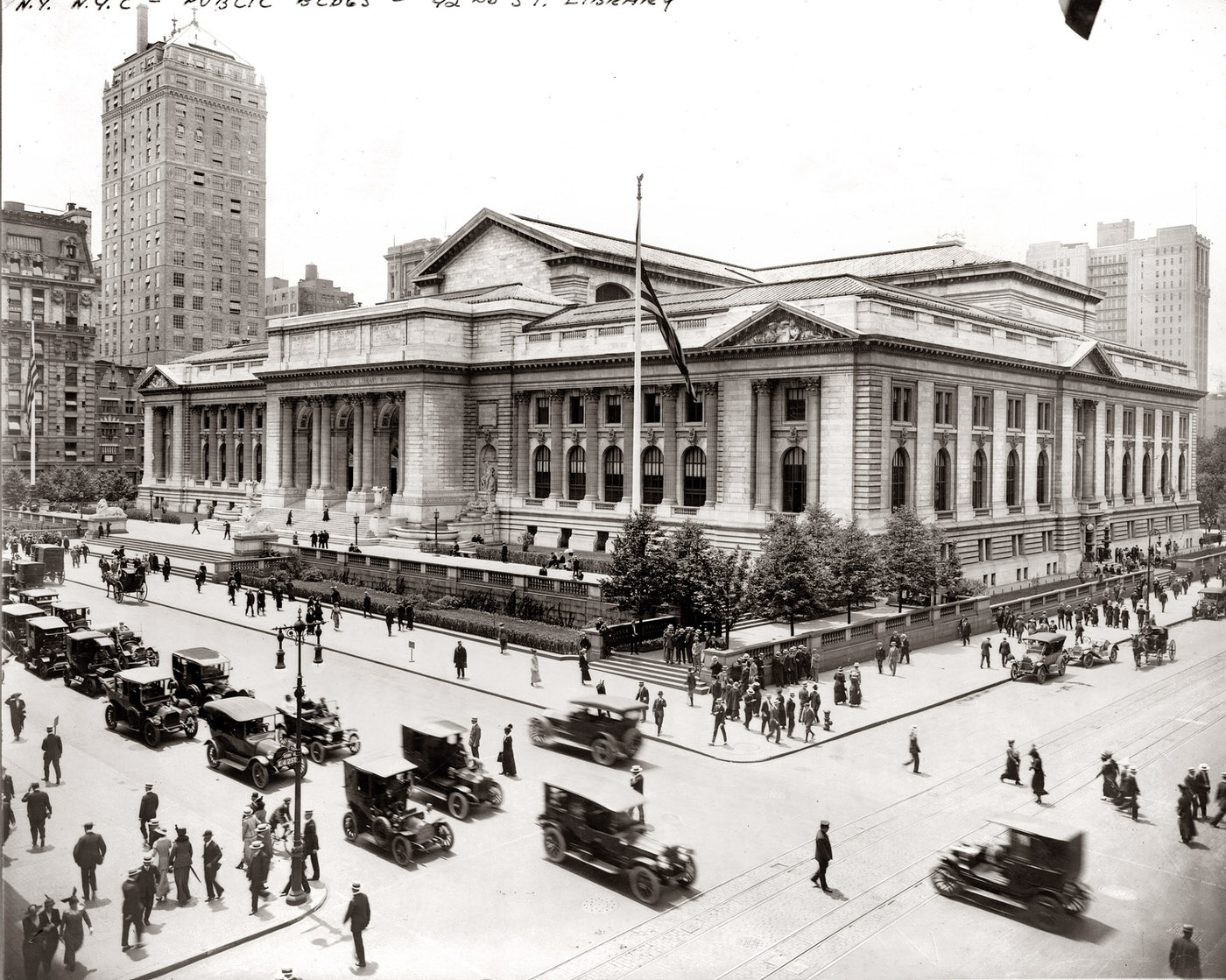

The 1910s marked a decade of rapid and defining transformation for New York’s Fifth Avenue. The street, once the exclusive domain of Gilded Age millionaires, was now a dynamic battleground between residential society and encroaching commerce. This struggle visibly reshaped the avenue’s architecture, its traffic, and its very purpose in the life of the city.

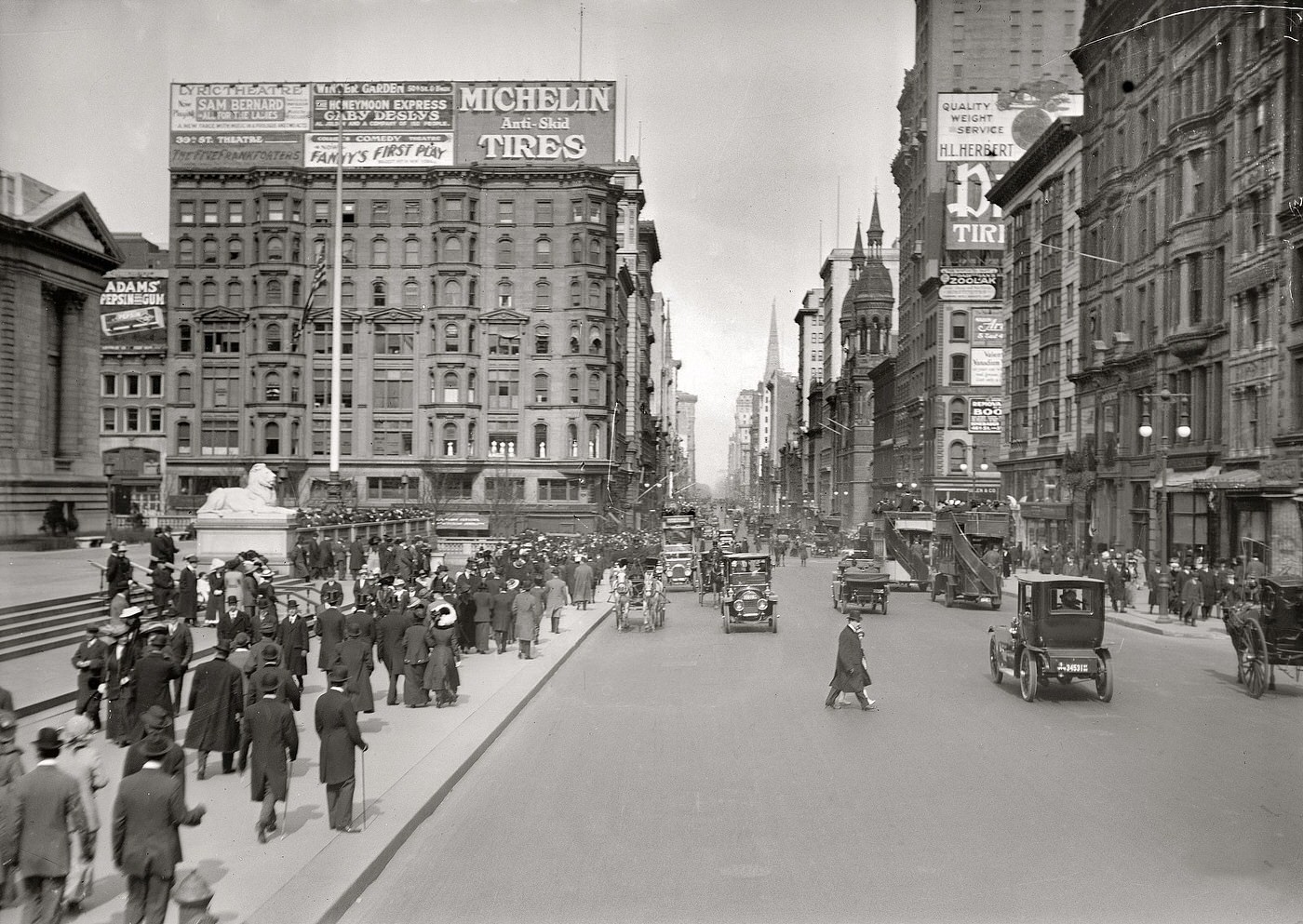

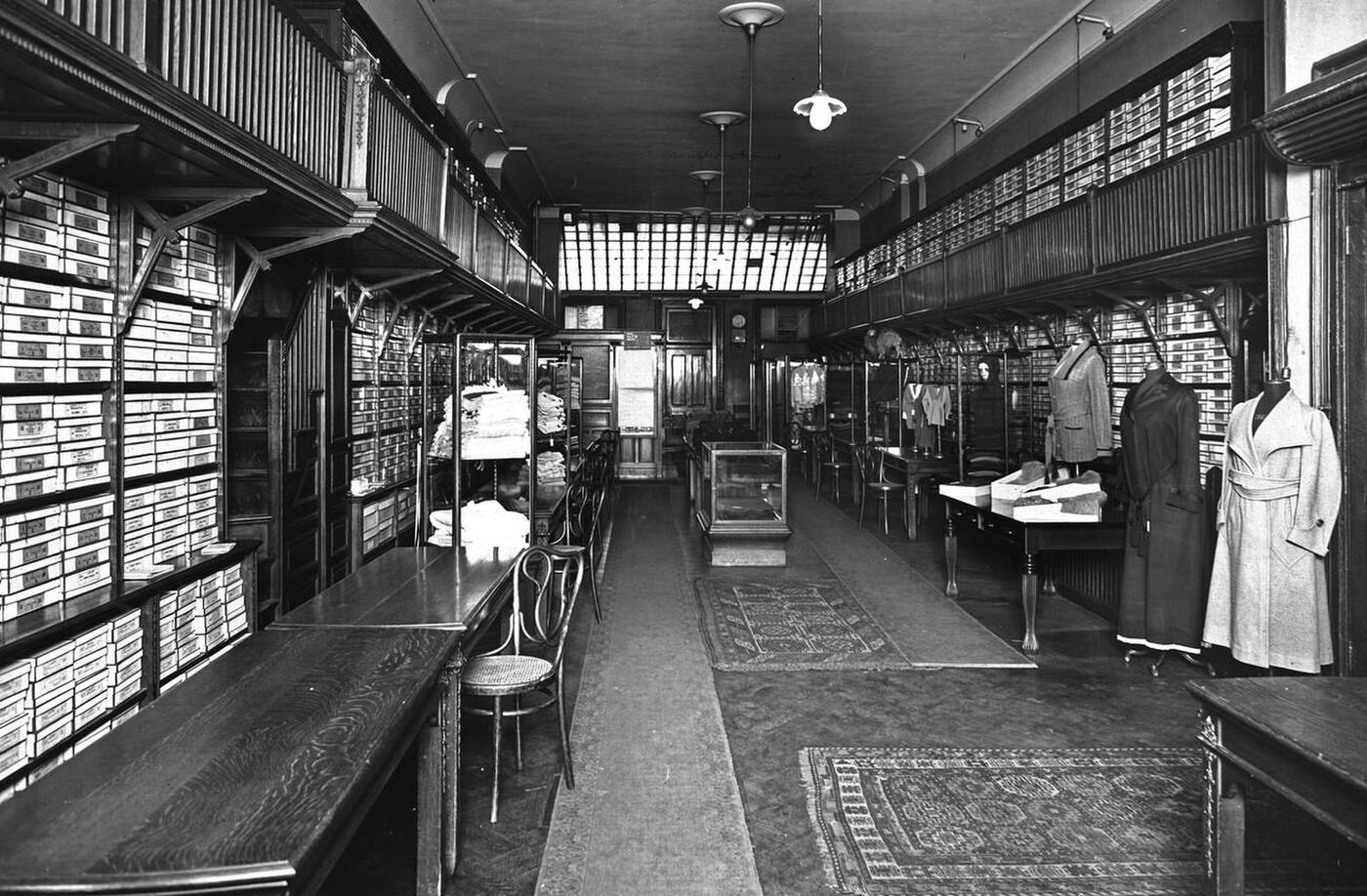

The most dramatic change was the retreat of the grand residential palaces. The southern stretch of “Millionaire’s Row,” below 59th Street, saw its opulent mansions fall one by one. In their place rose elegant, but distinctly commercial, buildings. Retailers like Lord & Taylor, which opened its grand new store at 38th Street in 1914, and B. Altman & Company at 34th Street, established the avenue as the city’s premier shopping destination. These new department stores were designed to be destinations in themselves, with impressive Italian Renaissance-style architecture that attracted the city’s fashionable shoppers.

Higher up the avenue, mansions were also being replaced by exclusive apartment buildings. The construction of 998 Fifth Avenue near 81st Street in 1912 set a new standard for luxury apartment living, offering a socially acceptable alternative for the wealthy who no longer wished to maintain a massive private home on the increasingly busy street. The demolition of the magnificent Vanderbilt “Triple Palace” at 51st Street began during this decade, signaling a definitive end to an era of private splendor on that part of the avenue.

Read more

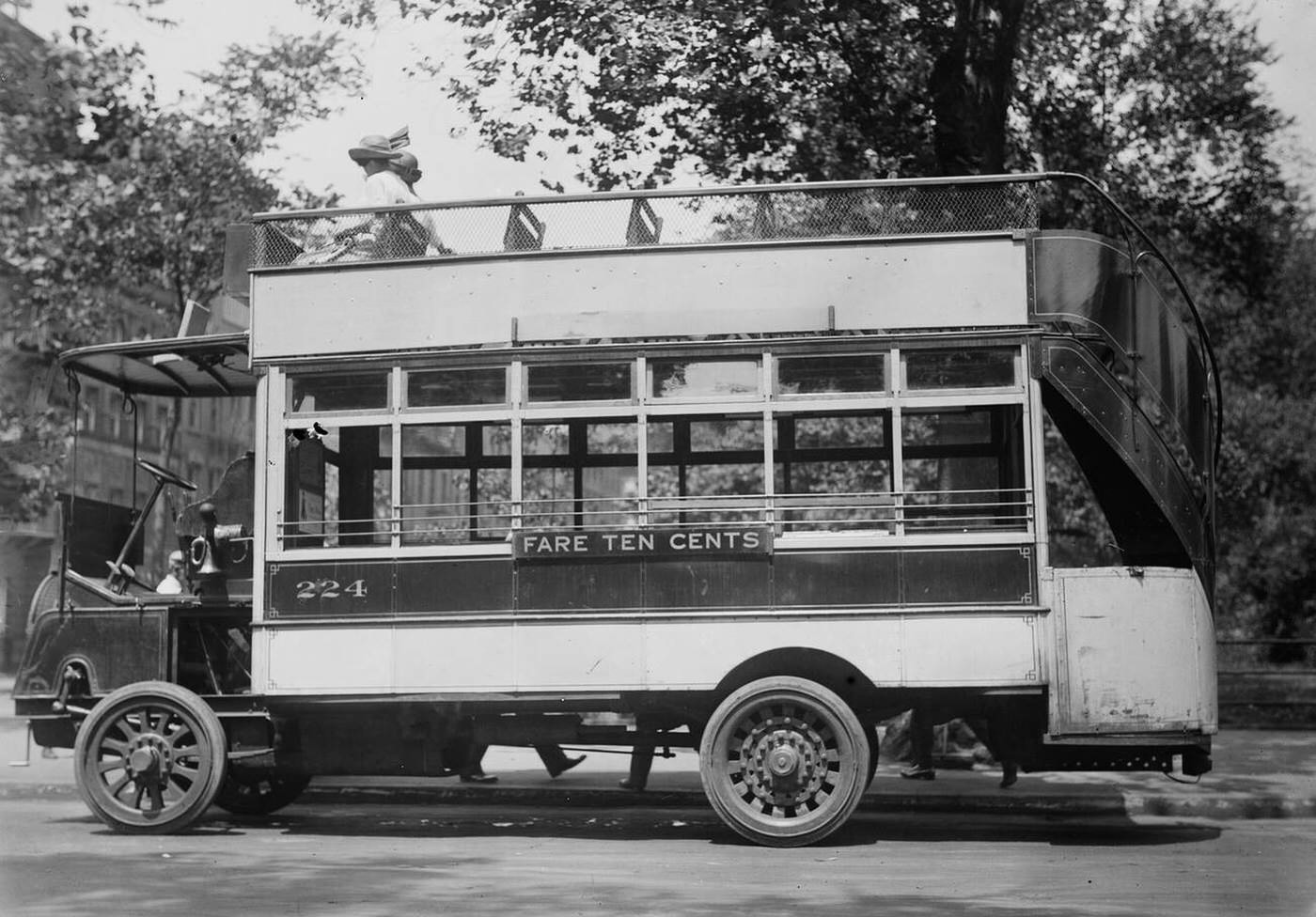

The street itself was a scene of controlled chaos. The 1910s was the decade where the automobile truly began to dominate horse-drawn carriages. This created unprecedented traffic jams. Fifth Avenue became so congested with a mix of motor cars, delivery wagons, and horse-drawn hansom cabs that the city had to take action. To manage the flow, the first traffic officer, Officer William Phelps, was stationed at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue. This effort would eventually lead to the installation of the first traffic light towers in the following decade.

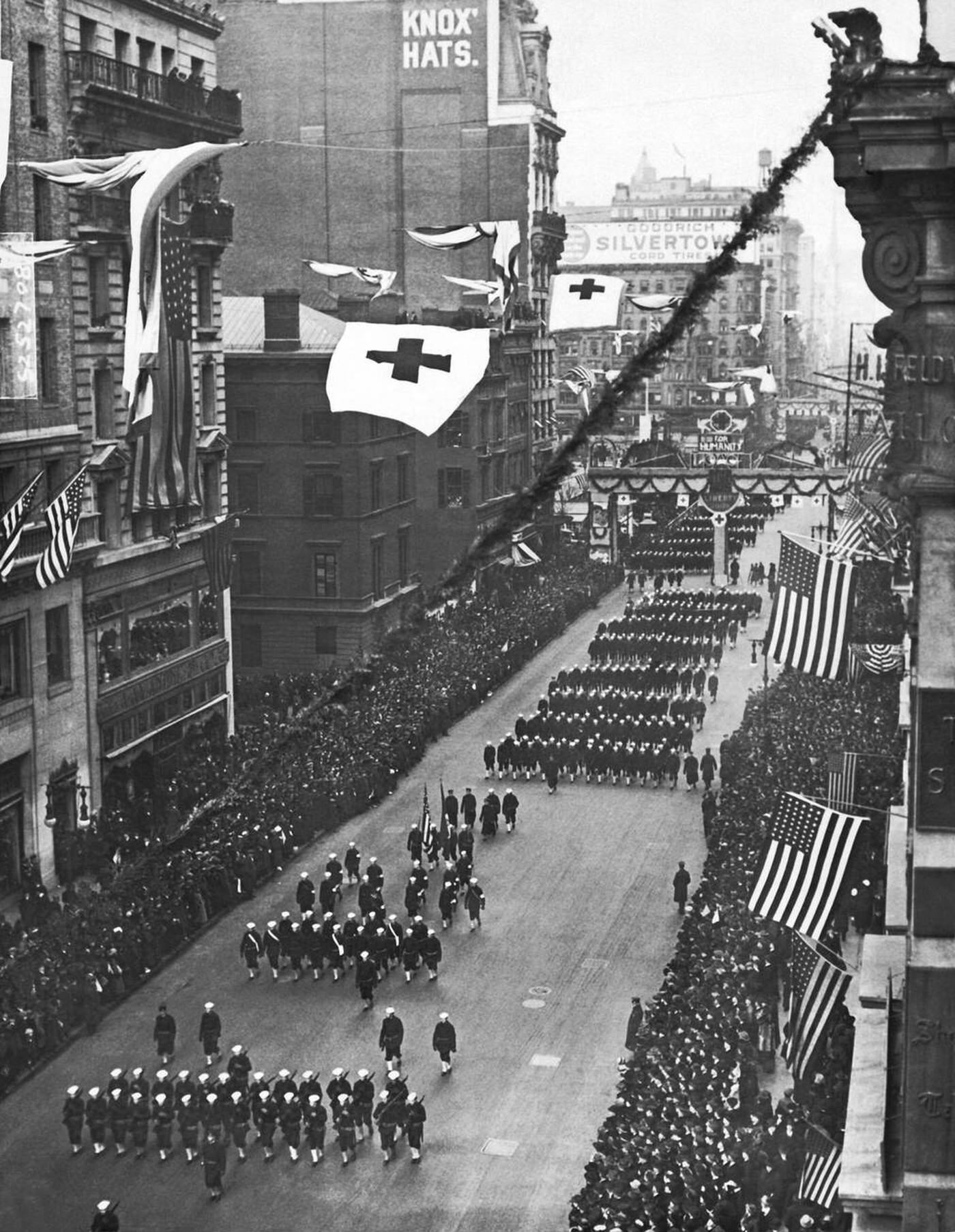

Fifth Avenue also solidified its role as the city’s ceremonial parade route. The street hosted events that captured the national mood. In August 1914, it was the site of the somber Women’s Peace Parade, where 1,500 women marched in silence to protest the outbreak of World War I. Just a few years later, the same avenue was filled with jubilant crowds and the sounds of marching bands, as soldiers, including the famous “Harlem Hellfighters” of the 369th Infantry Regiment, paraded up the avenue upon their return from the war in 1919.

Throughout the decade, the Fifth Avenue Association, a powerful group of business owners and residents, worked to regulate the avenue’s development. They fought to keep factories out of the area and established strict building codes to ensure that new construction maintained an air of sophistication. This preserved the street’s high-end character even as its function shifted from a private enclave to a public commercial thoroughfare.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings