On the morning of May 30th in the early 1900s, the Bronx would awake to the sounds of brass bands and marching feet. This was Decoration Day, a solemn and patriotic holiday set aside to honor the nation’s war dead. For the residents of the rapidly growing borough, it was a day of parades, speeches, and remembrance, an event that brought entire communities out onto the streets.

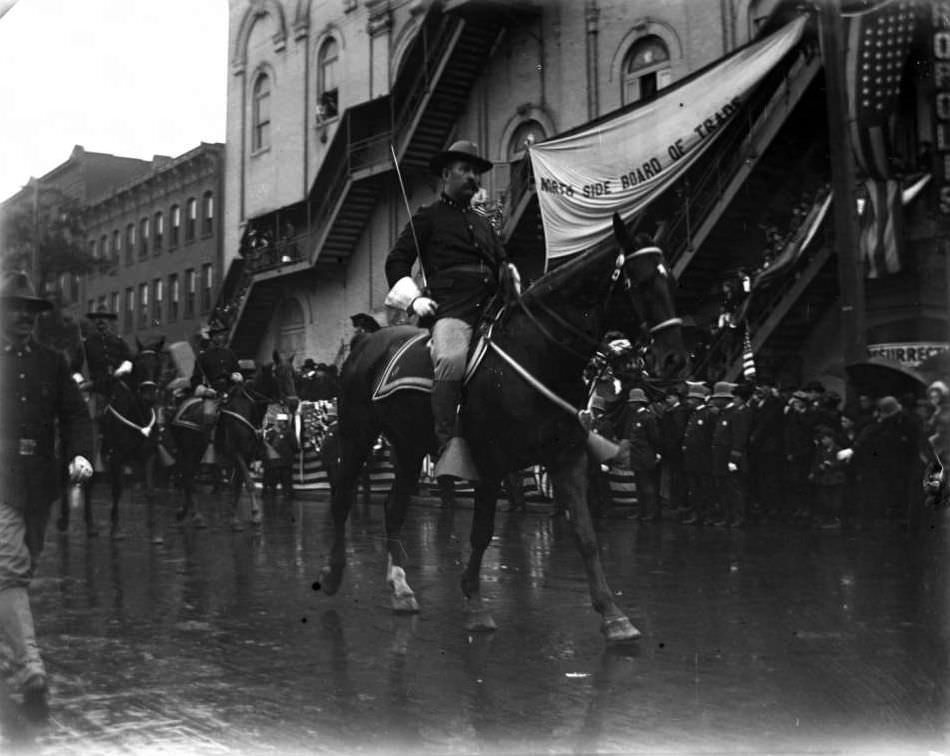

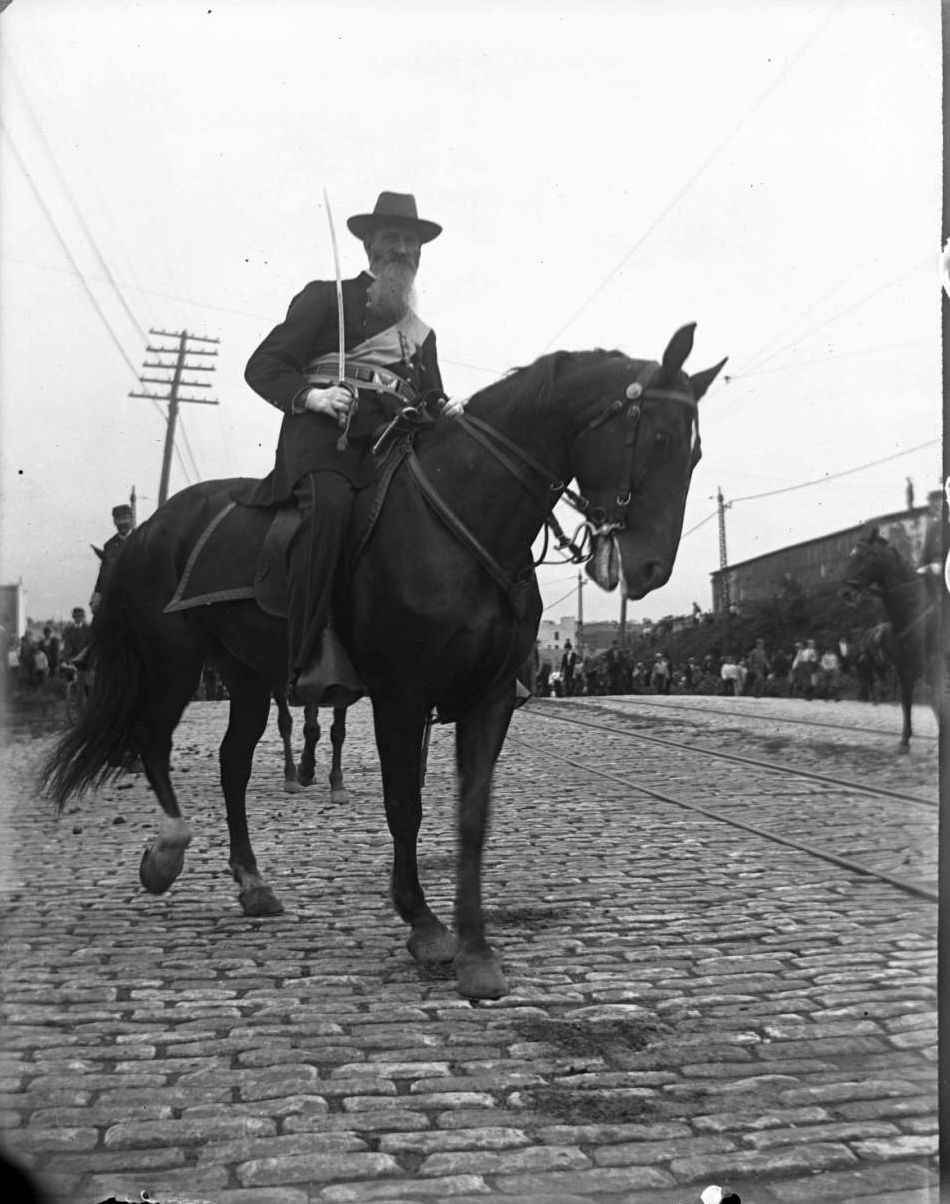

The processions were organized and led by the veterans themselves. Chief among them were the aging members of the Grand Army of the Republic, or G.A.R., men who had fought for the Union in the Civil War. Local chapters, like the Oliver Tilden Post and the Vanderbilt Post, formed the heart of the parade. By this decade, most of these veterans were in their 60s and 70s. While some still marched, many rode in open carriages provided for the occasion, their dark blue, brass-buttoned uniforms a direct link to the battles of a previous century.

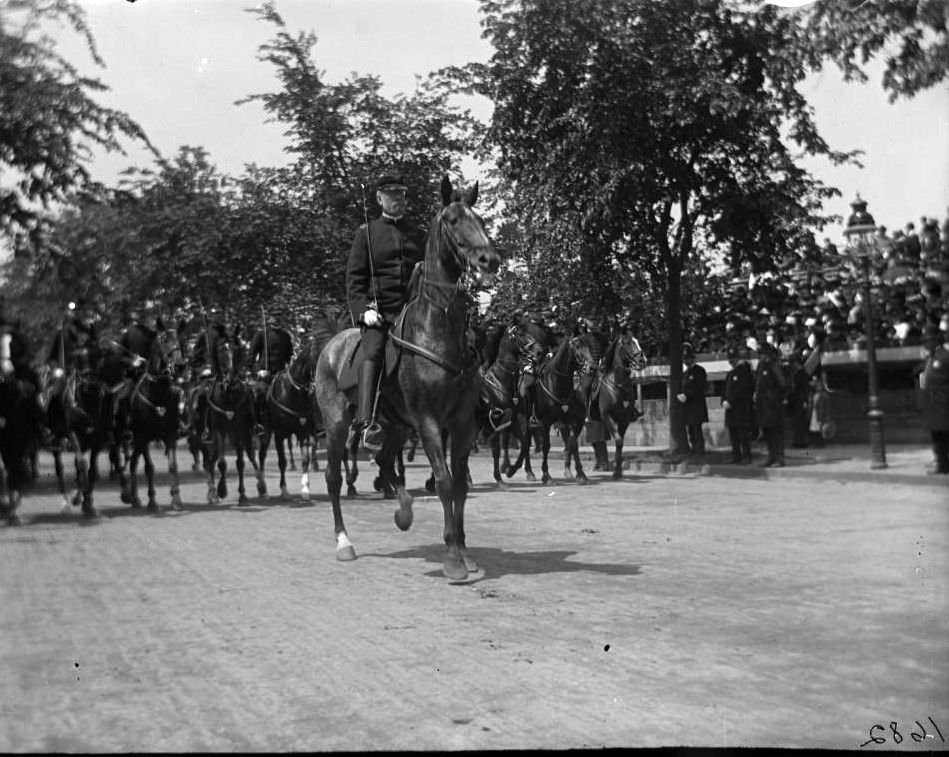

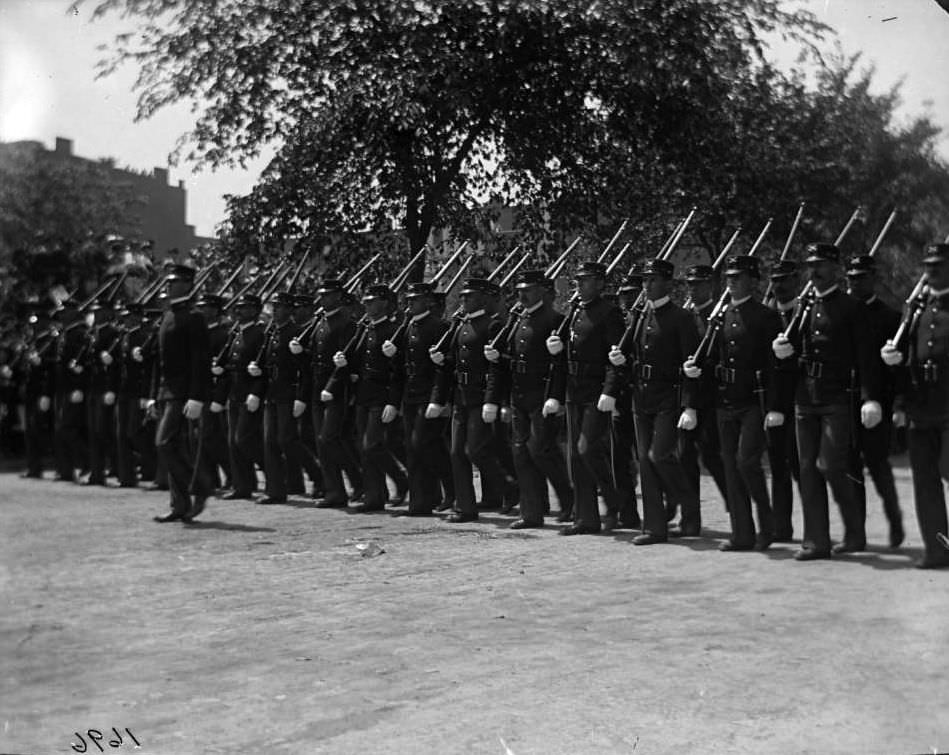

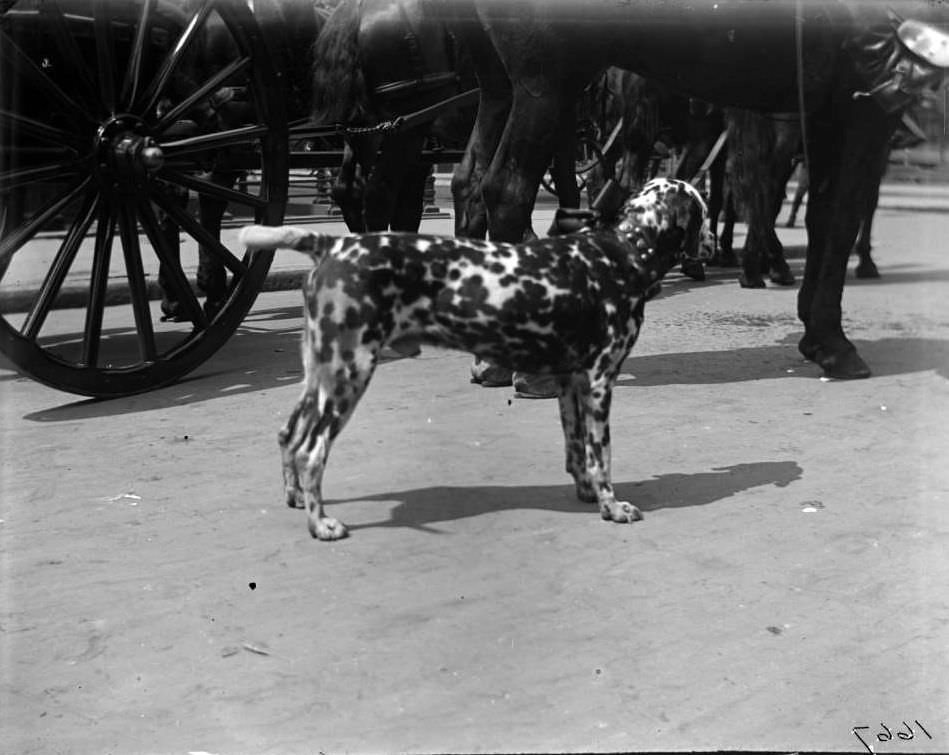

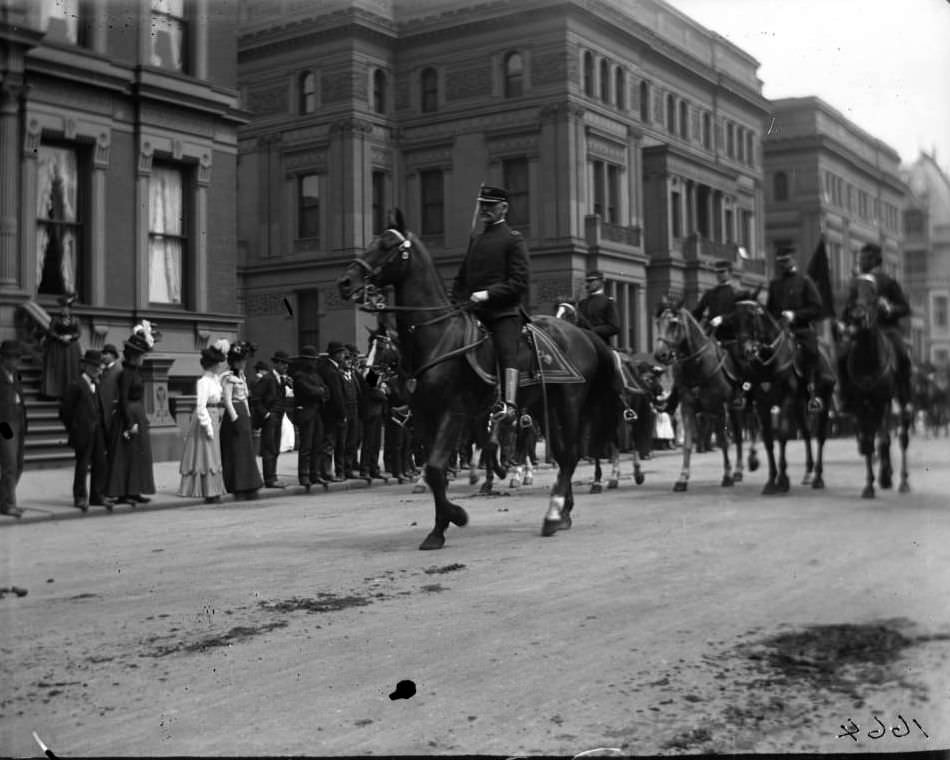

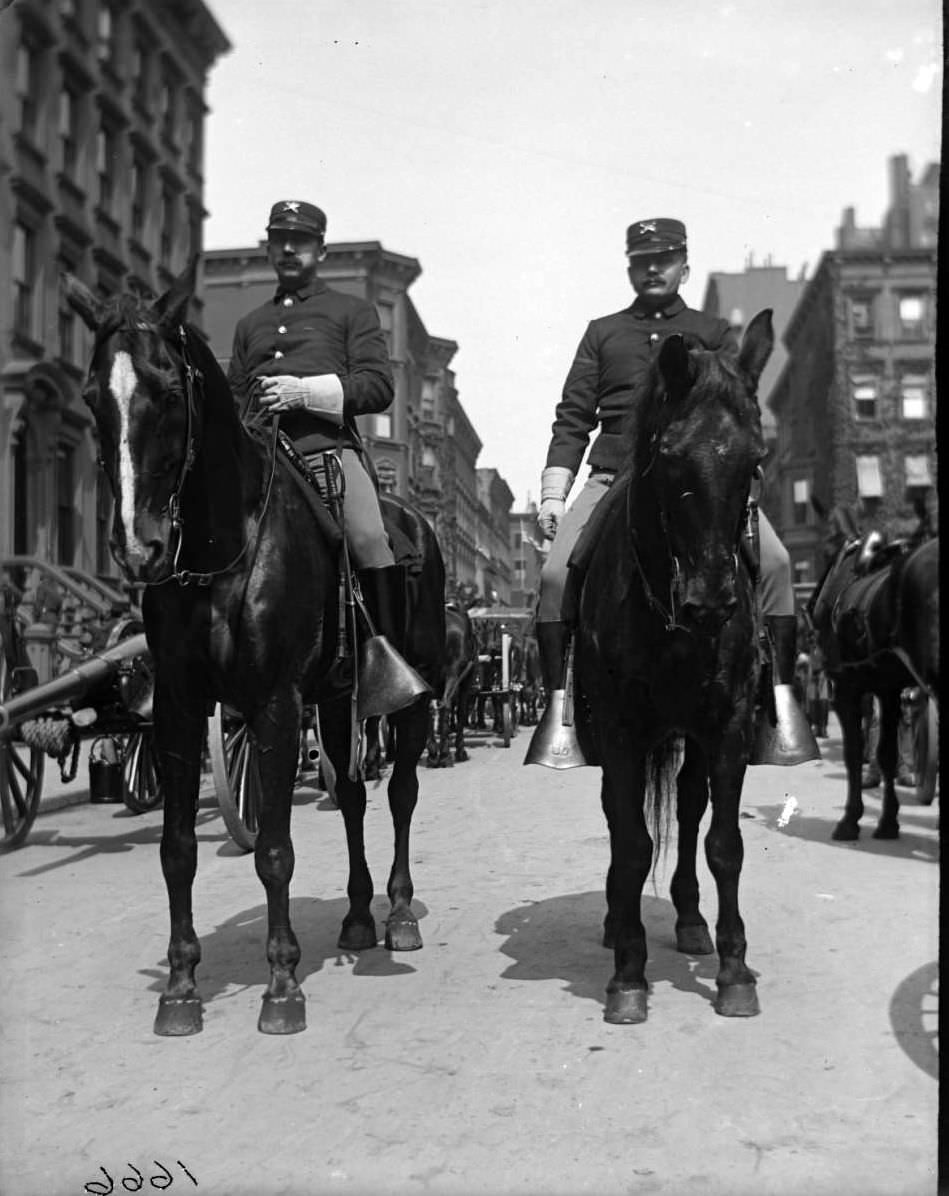

Following the Civil War veterans were the younger, more vigorous men of the United Spanish War Veterans. These men, who had served in the War of 1898, marched with military precision. The parade also featured local militia companies, the fife and drum corps of community organizations, and hundreds of public schoolchildren, each carrying a small American flag and a bouquet of fresh spring flowers.

Read more

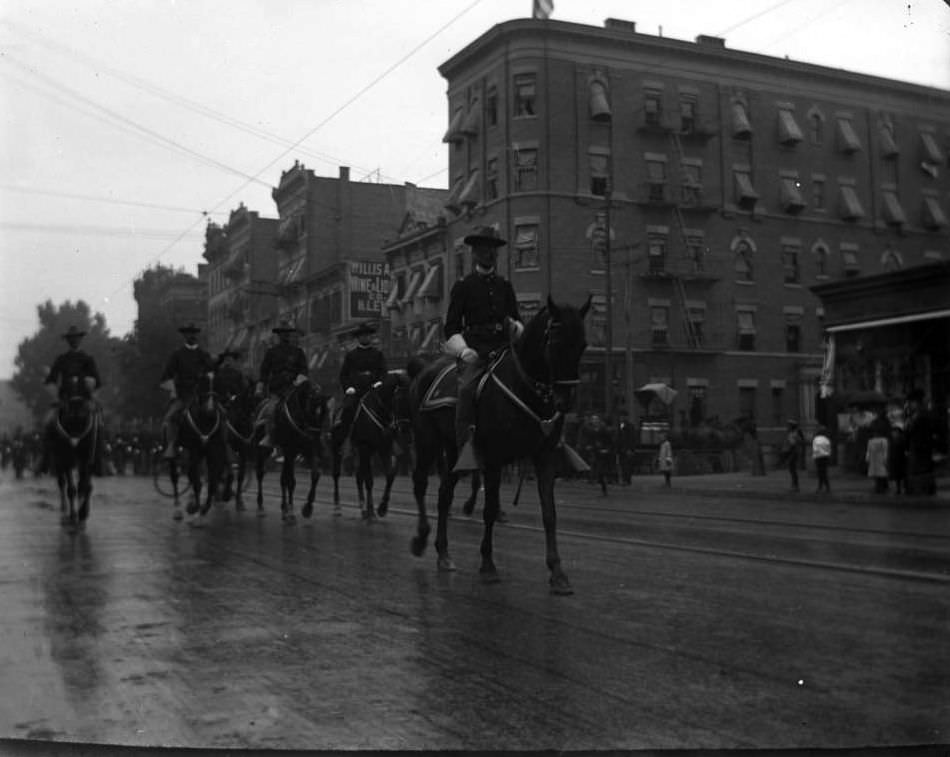

A typical parade route would form on a major thoroughfare like Washington or Third Avenue. Led by a police escort and a Grand Marshal chosen from the veterans’ ranks, the procession would move north through the borough. Families crowded the sidewalks, the men with their hats held over their hearts as the American flag passed by. The fronts of apartment buildings and businesses were decorated with flags and patriotic bunting.

The final destination for the main Bronx parade was often the soldiers’ plot at Woodlawn Cemetery. Here, the festive air of the procession gave way to a more somber ceremony. The veterans and spectators would gather among the gravestones, which were each marked with a small flag. A local clergyman would offer a prayer, and a dignitary would deliver a formal address.

The core of the service was steeped in tradition. A chosen student or veteran would recite Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, its words echoing across the quiet grounds. A band would play somber hymns like “Nearer, My God, to Thee.” At the ceremony’s conclusion, a firing squad from a local National Guard unit would fire a three-volley salute into the air. The final act belonged to the children. Moving through the rows of headstones, they would place their bouquets on the graves of the soldiers, fulfilling the original purpose of Decoration Day.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings