On October 25, 1917, New York City transformed Central Park into a full-blown war exhibit for Liberty Day. This event was part of a massive national push by the federal government to raise money for World War I through the sale of Liberty Bonds. It wasn’t just about fundraising—it was about showing the public what was at stake.

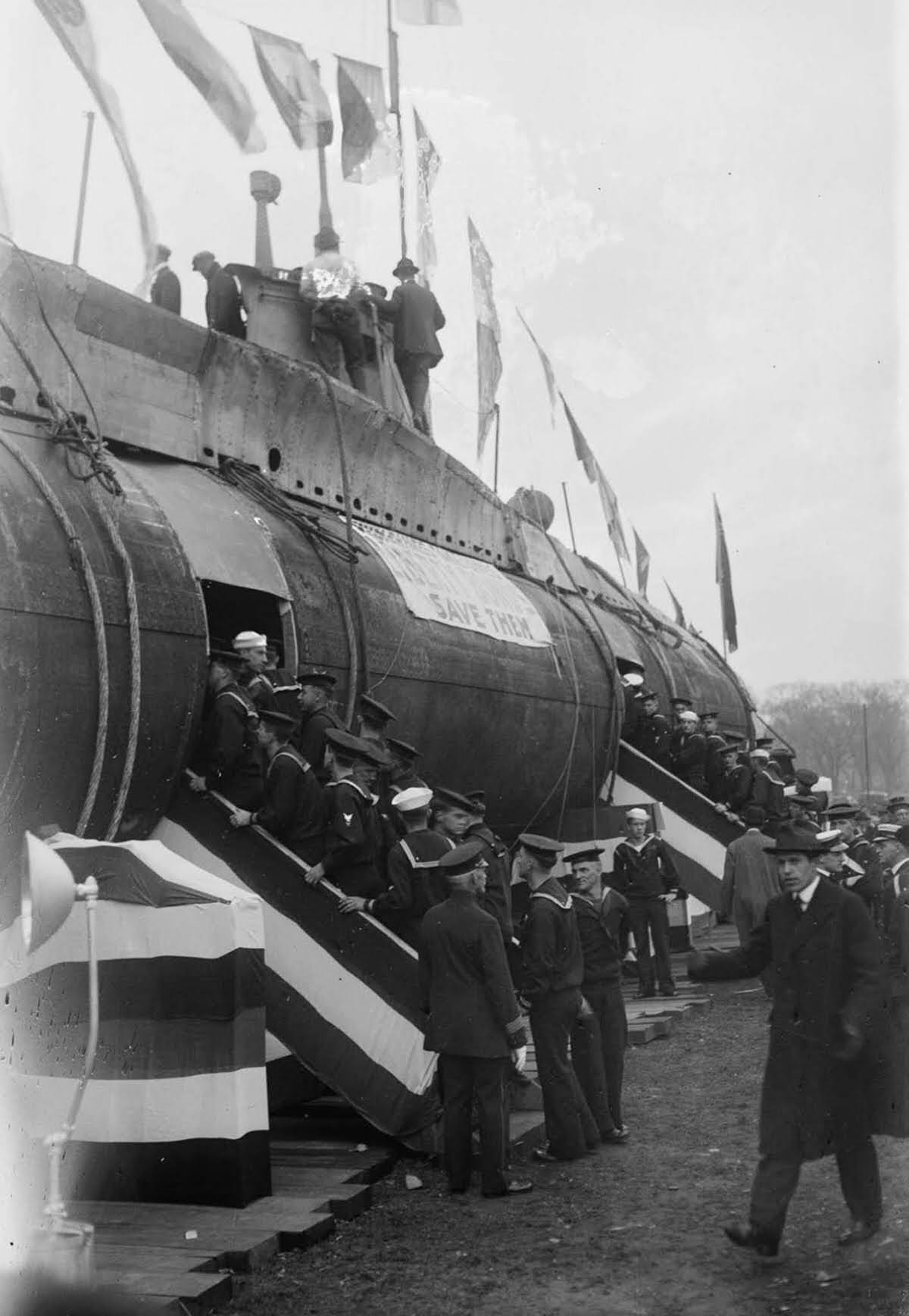

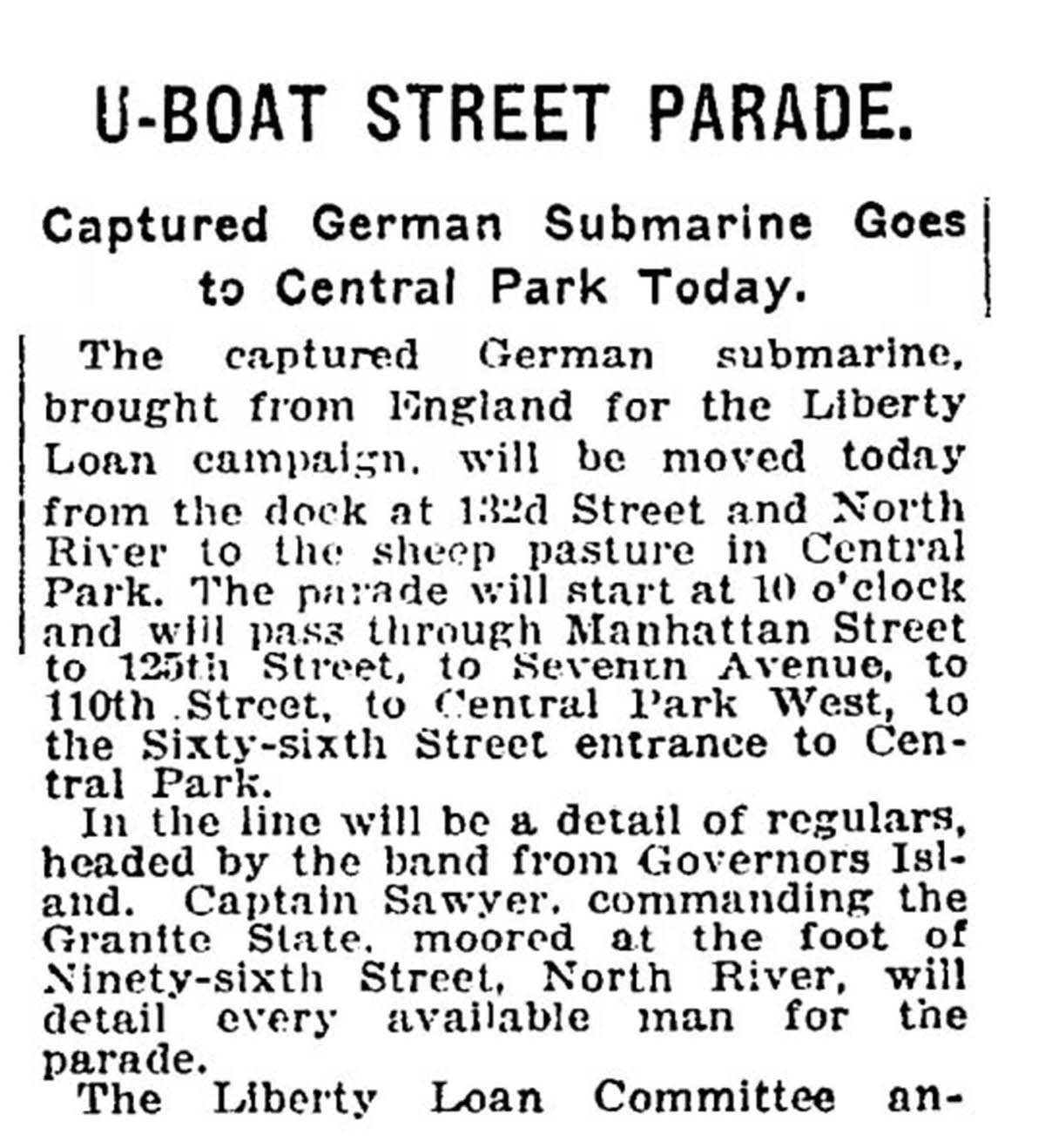

In the middle of Central Park, crowds gathered to see something they had never seen before: a real German U-boat. The SM UC-5 was a captured enemy submarine, and it was placed in the park as a symbol of victory and warning. It had sunk 29 ships before being caught. The submarine sat silent among trees and grass, now surrounded not by ocean but by American civilians.

Across the city, Liberty Day was in full swing. A Caproni bomber flew low between buildings, its three engines roaring over the heads of New Yorkers. Military motorcycles moved down Fifth Avenue in formation, while tanks and trucks joined the march. Flags hung from buildings. Some people held signs that read, “Submarines take lives; Liberty Bonds save them.” These weren’t just words. The government was serious about selling bonds, and the visuals made the message hard to ignore.

Read more

Liberty Bonds were designed to help pay for the war. The government had a plan. One-third of the war’s cost would come from taxes. The other two-thirds had to come from public investment. The bonds gave everyday people a chance to put money toward the military’s efforts. They were told their money would help win the war and bring American troops home safely.

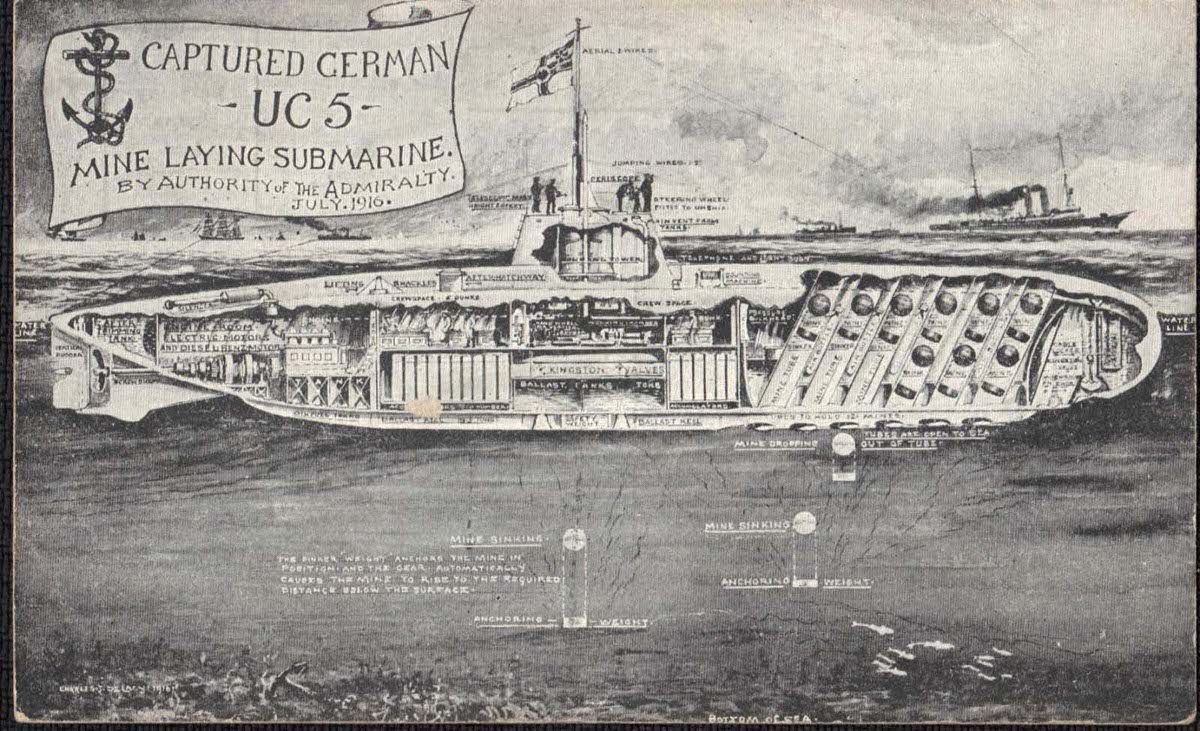

The UC-5 submarine had a dark history. Commissioned into the German Imperial Navy in 1915, it was a small but deadly piece of technology. It had a top speed of just over seven miles per hour and could dive up to 160 feet. A crew of fourteen men operated the vessel, launching torpedoes at Allied ships. It was a cheap but effective weapon in Germany’s plan to cut off supplies to Britain.

In April 1916, the UC-5 ran aground and was captured. The British put it on display in London before sending it to New York. Its arrival in Central Park turned heads. Many had never seen a submarine in real life. Now, they could walk right up to one used by the enemy. The message was clear: the enemy was real, and support was urgent.

The impact of Liberty Day was seen in numbers. More than 20 million people bought Liberty Bonds. At the time, there were only 24 million households in the entire country. The bond drive raised more than $17 billion. Taxes brought in $8.8 billion. Together, the total amount helped fund the war and gave citizens a direct way to participate.

Every part of Liberty Day was designed to pull people in. The war felt far away to many Americans, but seeing weapons, planes, and captured machines made it real. The displays weren’t just for show. They were tools to build emotion and drive action. People didn’t just look—they signed up, bought bonds, and joined the cause.

The Caproni bomber was one of the largest aircraft of its time. Its low flight over the city was a rare sight. The roar of its engines echoed between skyscrapers. It wasn’t carrying bombs over New York, but the symbolism was strong. It showed what American money could support in the skies above Europe.

In the same way, the motorcycles and tanks in the parade weren’t headed to battle, but they gave people a chance to see where their bond dollars were going. Children watched wide-eyed. Adults reached for their wallets. Posters and signs filled the streets with slogans that linked money to safety, and support to patriotism.

Liberty Day in Central Park wasn’t quiet or calm. It was loud, crowded, and built to move people. Seeing a German submarine in the middle of New York City left no doubt that the war was close to home. The event turned Central Park into a display of strength, sacrifice, and national purpose. It made war real for millions of people who would never see a battlefield.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings