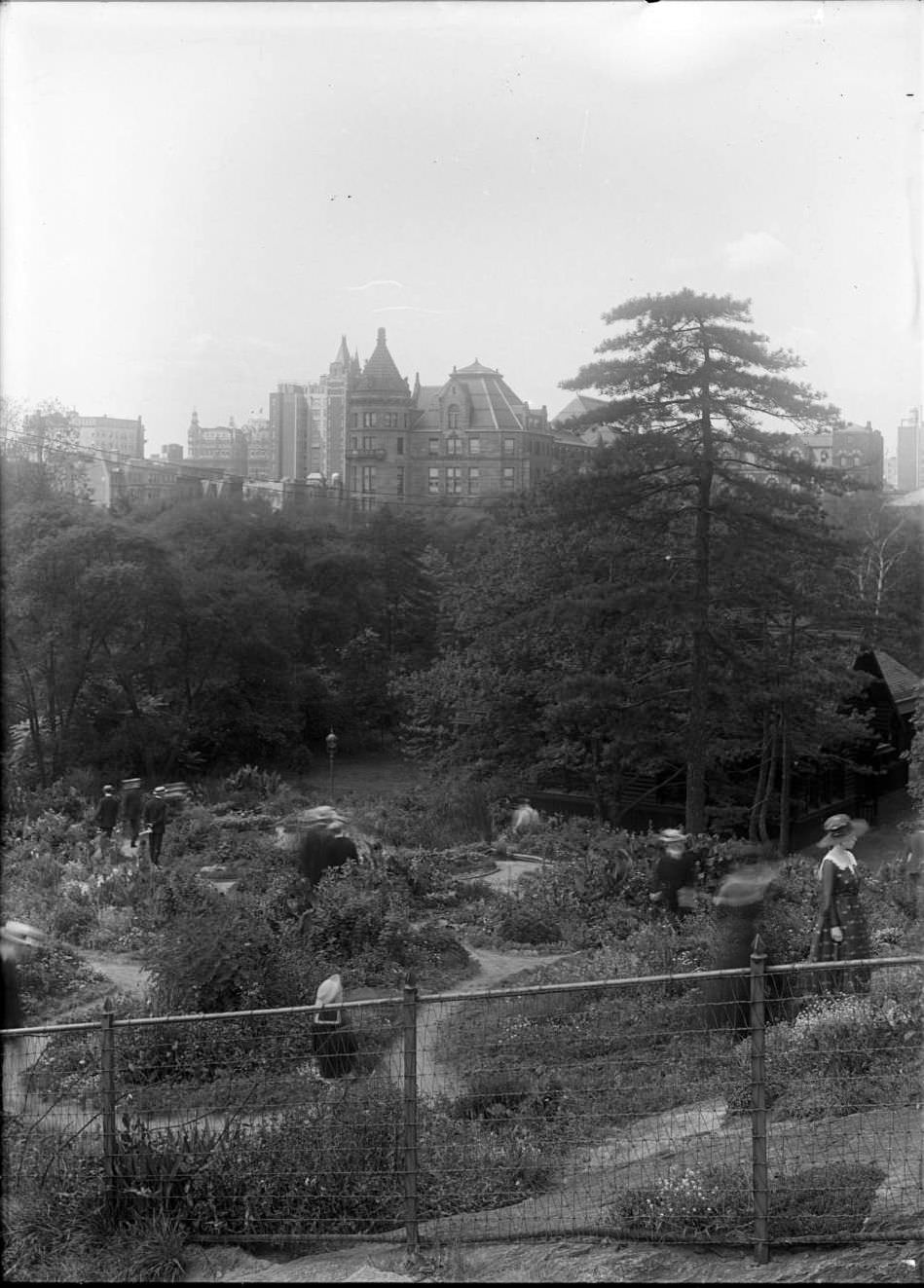

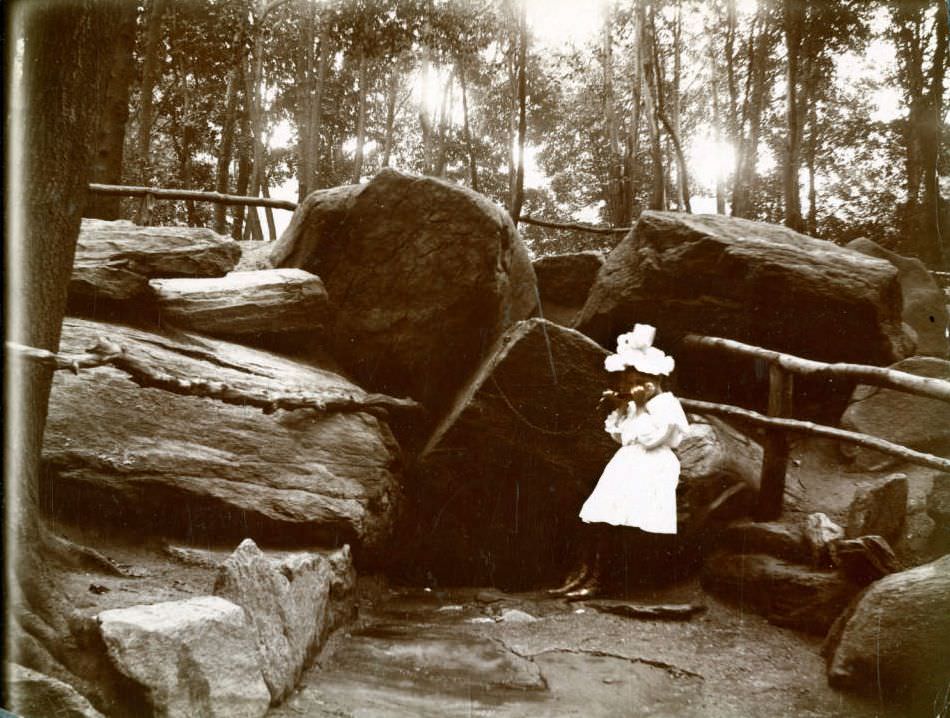

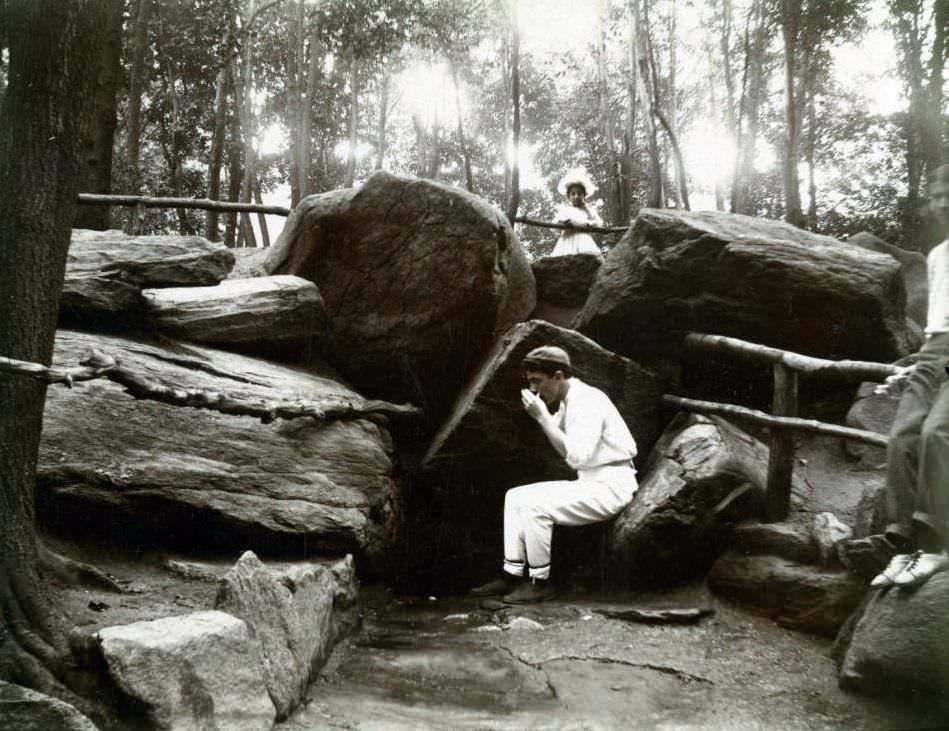

In the 1890s, more than thirty years after its completion, Central Park was the great stage for New York City’s public life. It was a meticulously managed landscape of winding paths, formal promenades, and rustic woodlands, where the city’s social rituals were on full display. The decade was a time of transition, when the elegant, horse-drawn carriage began to share the park’s drives with a revolutionary new machine: the bicycle.

The primary social event of any fair-weather day was the carriage parade. Each afternoon, a procession of New York’s wealthiest families would circle the park’s main drives. They rode in elegant Victorias, Broughams, and other fine carriages, pulled by perfectly groomed horses and driven by coachmen in formal livery. This slow-moving parade was a chance to see and be seen, a rolling display of wealth and status against the backdrop of the park’s curated scenery. The most popular routes were along the East and West Drives, where spectators could sit on benches and watch the procession.

This traditional scene was disrupted by the “bicycle craze” that swept the nation. The new “safety bicycle,” with its two equal-sized wheels, was easier and safer to ride than earlier models, and it became enormously popular with both men and women. Central Park’s smooth, winding drives were the ideal place to ride. Cycling was seen as a modern and liberating activity. It allowed for more freedom of movement than a chaperoned carriage ride and brought different social classes into closer contact on the park’s paths.

Read more

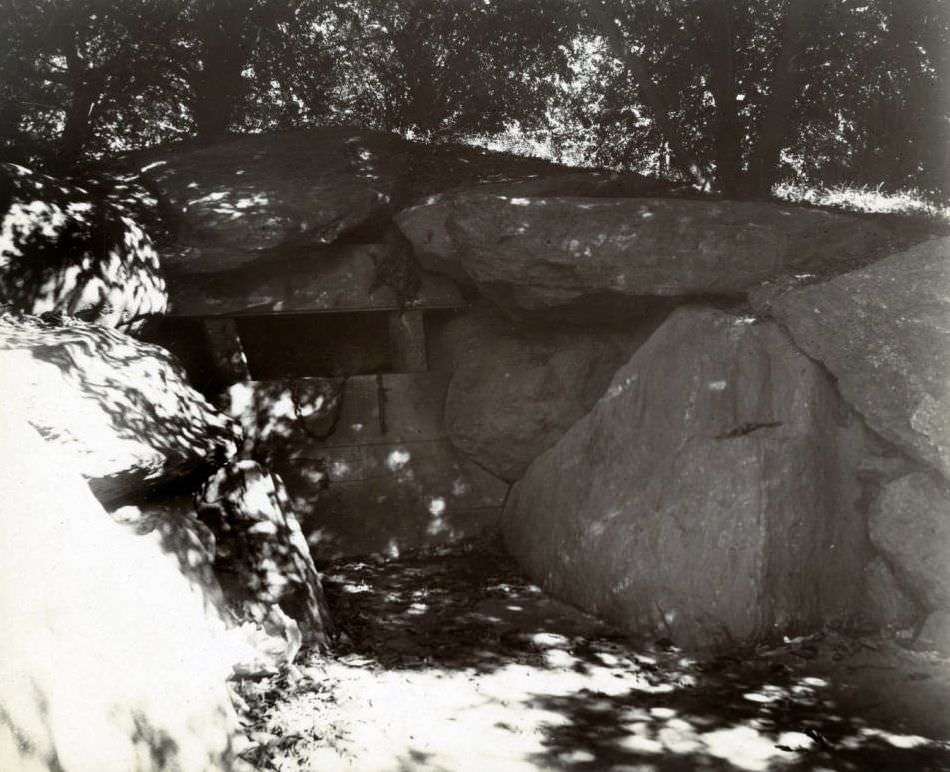

Visitors to the park flocked to its well-established landmarks. The Mall, a wide, straight promenade lined with American elm trees, was the park’s formal centerpiece, a place for strolling. It led to Bethesda Terrace, the ornate, two-level plaza with its grand staircase and the famous Angel of the Waters statue. The Menagerie, the park’s early zoo located near the Arsenal building, was a popular destination for families to see its collection of animals. The Belvedere Castle, a stone folly perched high on Vista Rock, offered panoramic views of the park’s landscapes.

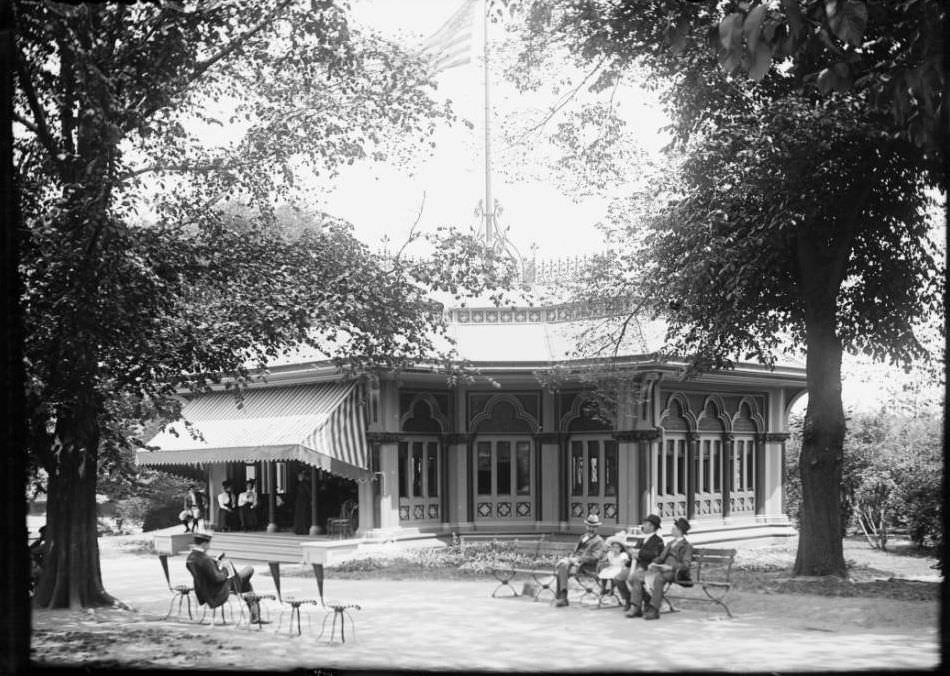

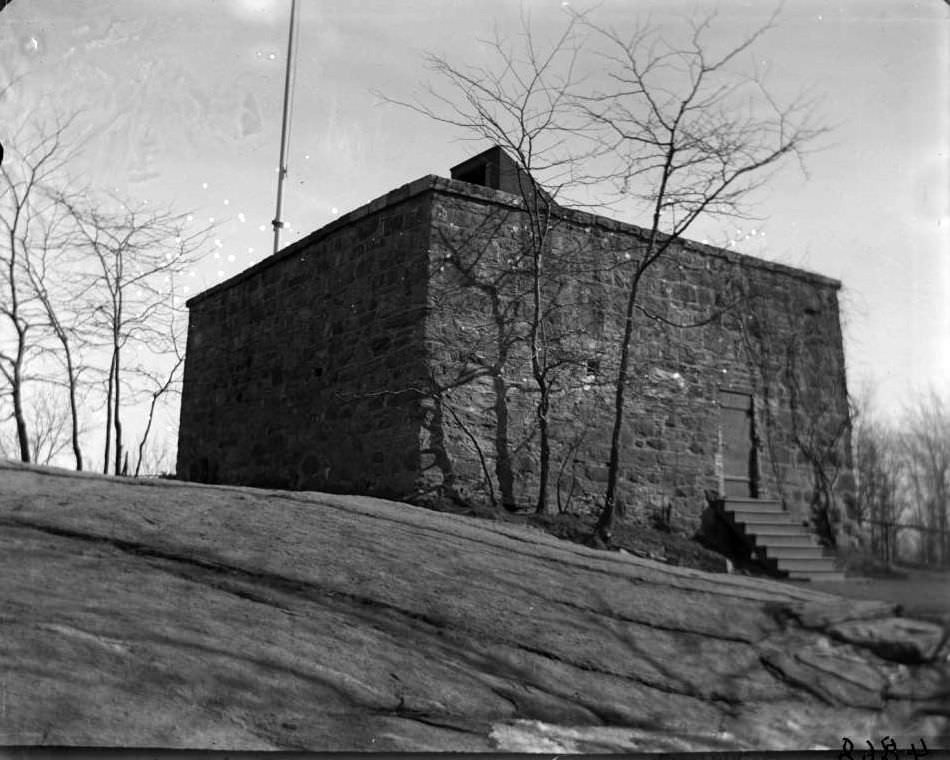

The park’s use changed dramatically with the seasons. In the summer, New Yorkers would hire rowboats on the Lake or attend concerts at the music pavilion. But the most popular activity of the year was ice skating. As soon as the ice on the Lake was thick enough, a red ball would be hoisted on a pole at the Belvedere Castle, signaling to the city that skating was permitted. Tens of thousands of people from all walks of life would descend on the park, spending the day gliding across the vast frozen surface.

Throughout this decade, the park was still governed by strict rules. The ethos of its designers, which favored quiet contemplation and scenic appreciation, was enforced by numerous “Keep off the Grass” signs. The park’s great lawns were largely seen as visual elements, not spaces for active, unstructured recreation like picnics or games.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings