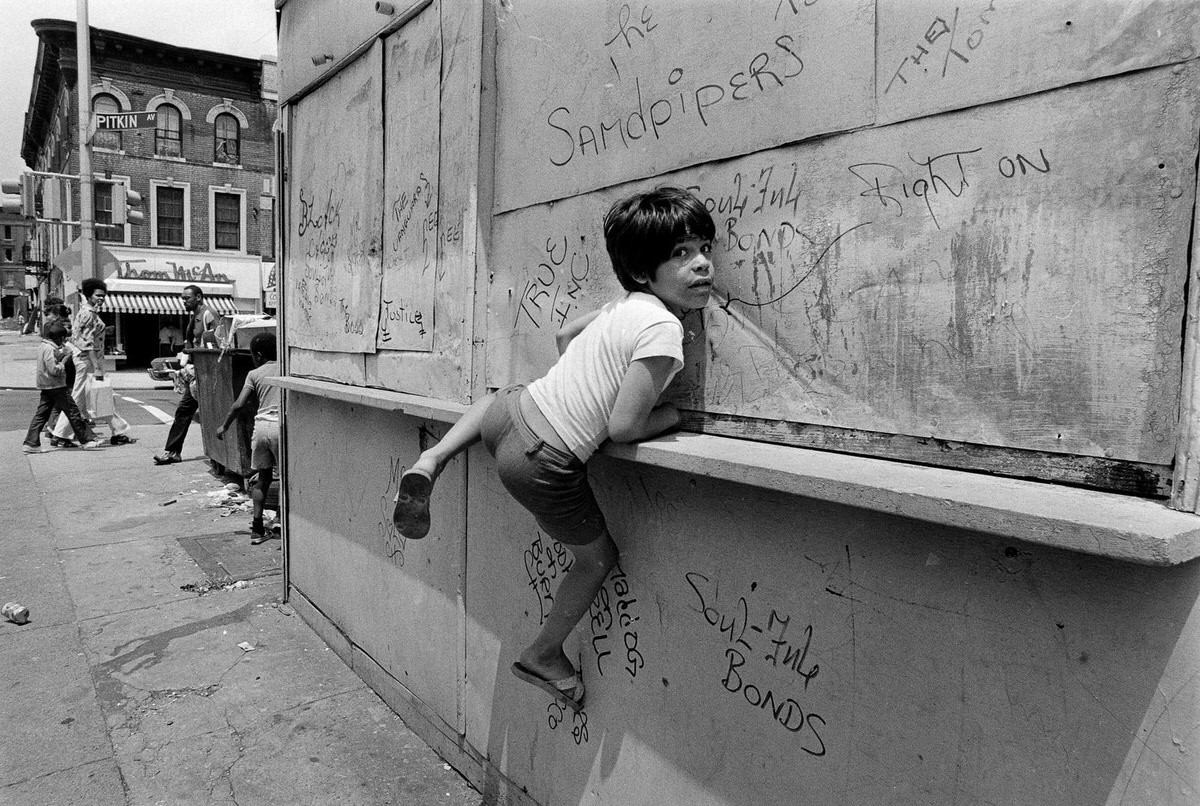

In the 1970s, Brownsville, Brooklyn stood out as one of New York City’s most troubled neighborhoods. Located in eastern Brooklyn, it was marked by high crime, abandoned buildings, and a deep sense of isolation from the rest of the city. City services were stretched thin. Police presence was limited, and emergency response times were slow. Piles of garbage often sat uncollected on the streets. Broken streetlights left entire blocks in the dark for days.

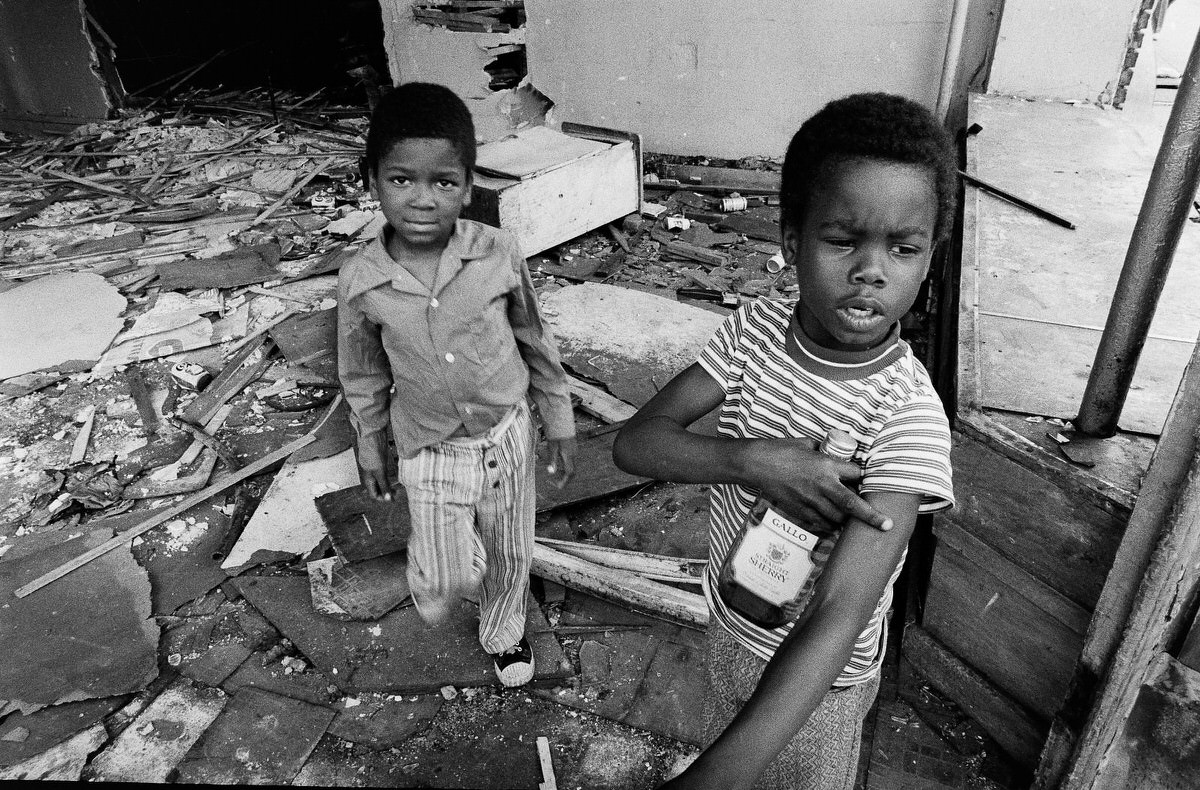

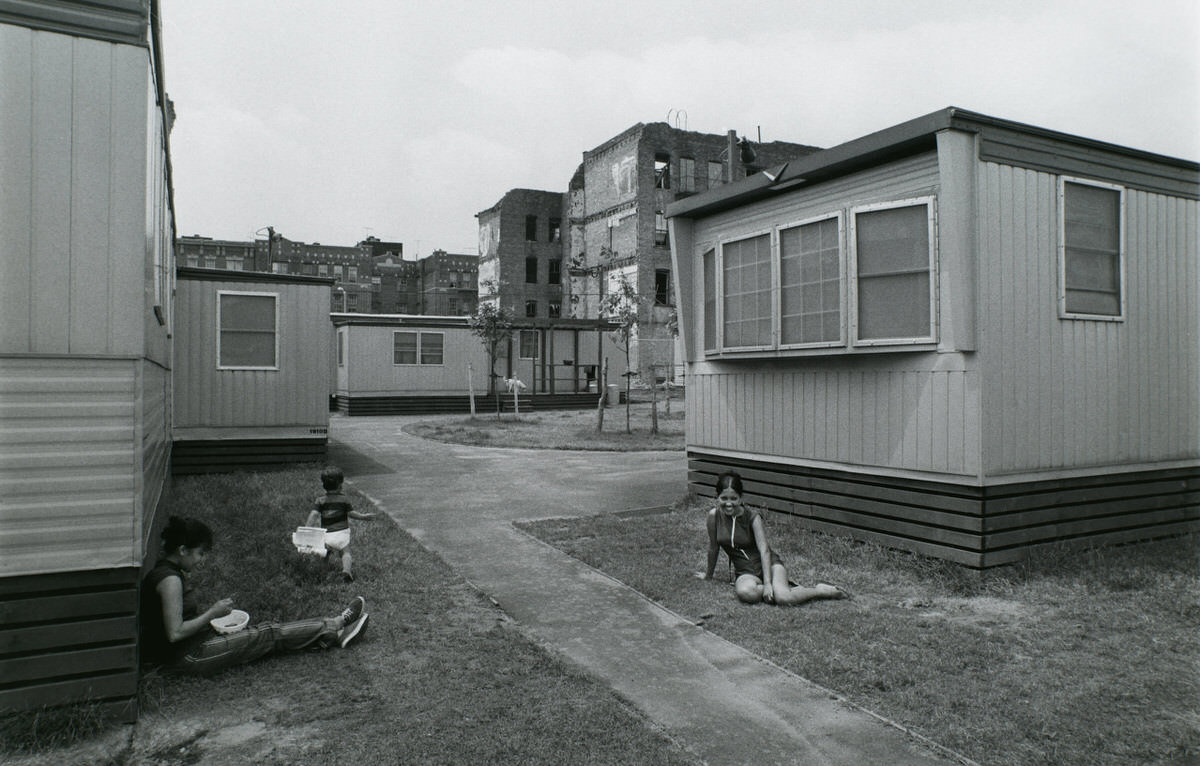

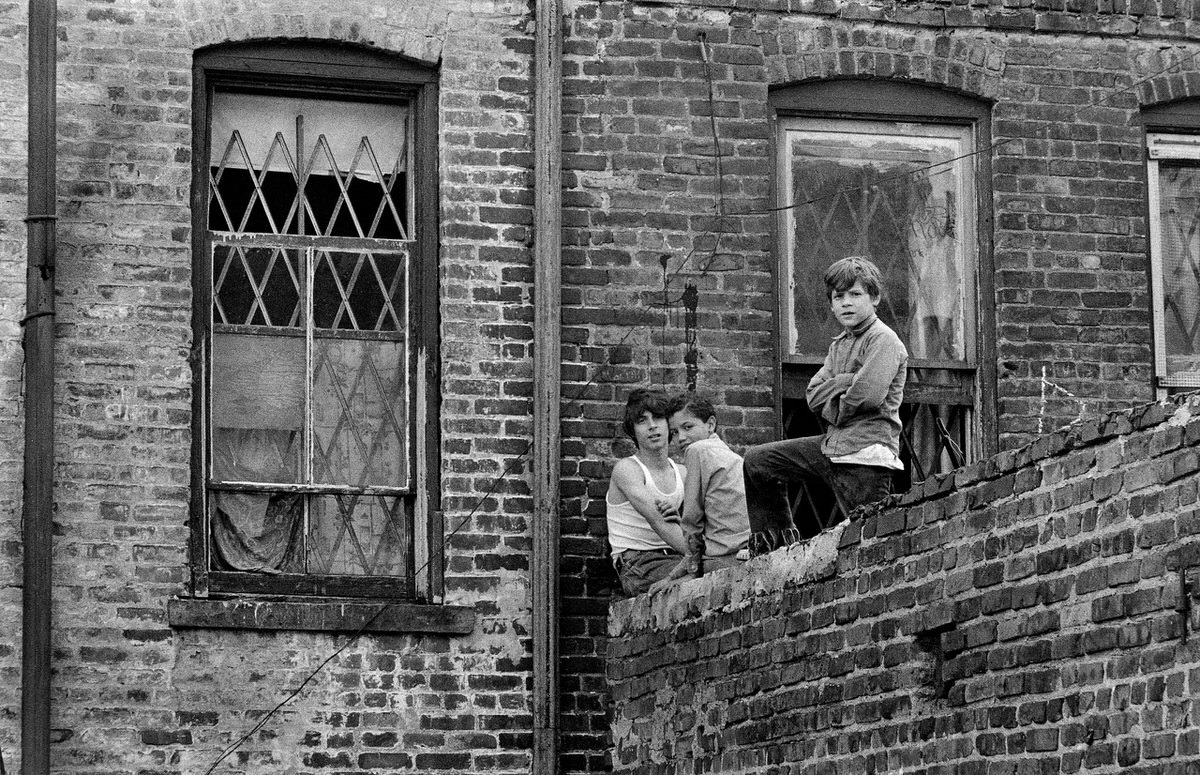

Brownsville’s housing stock had been aging for decades. Many buildings were built in the early 20th century and had not been updated. Tenement-style apartments often lacked working heat or running water. Fires were common. Landlords, unable or unwilling to maintain properties, sometimes walked away. As a result, buildings were left to decay. In some areas, entire blocks had been burned out or bulldozed, leaving gaps of rubble between the surviving homes.

The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) had constructed multiple public housing projects across Brownsville, such as the Langston Hughes Houses and the Van Dyke Houses. These complexes were meant to provide affordable housing, but by the 1970s, many were overcrowded and poorly maintained. Hallways and stairwells smelled of urine and stale air. Elevators were often broken. Residents relied on themselves for security.

Read more

Drugs hit the streets hard during this time. Heroin was sold openly in some parts of the neighborhood. Needles could be found in playgrounds, stairwells, and alleyways. Addiction tore families apart. Many children were raised by grandparents or a single parent. Some dropped out of school early to help support the family or simply to survive.

Public schools in Brownsville struggled. Overcrowded classrooms, low test scores, and old materials were common. Some schools had metal detectors at the entrance. Students faced daily challenges outside and inside the classroom. Teachers often came from outside the neighborhood and didn’t stay long. Despite these challenges, local parents fought to improve conditions.

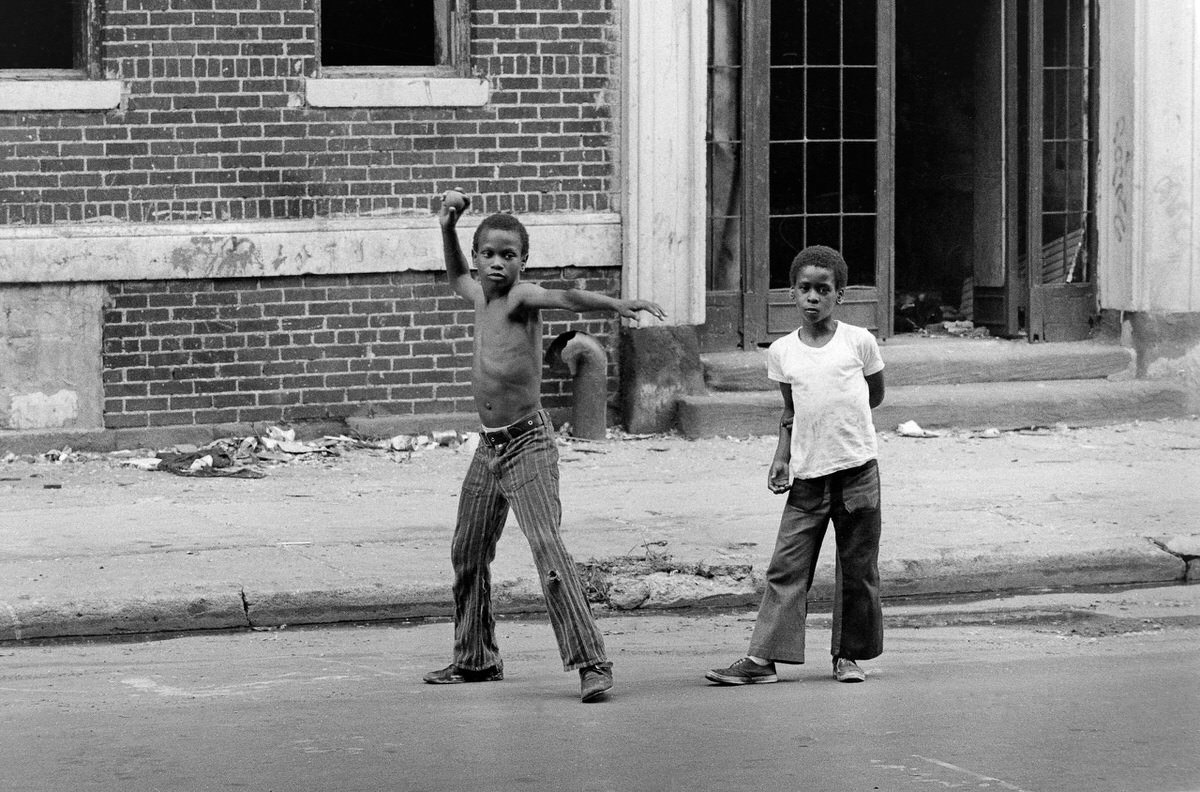

Street gangs controlled some areas. Turf battles between rival groups led to violence that spilled into parks, schools, and corner stores. Young people, often lacking safe outlets or activities, got pulled into the street life. The sound of gunfire was not rare. Residents learned to drop to the floor when shots rang out and to avoid certain blocks at certain times of day.

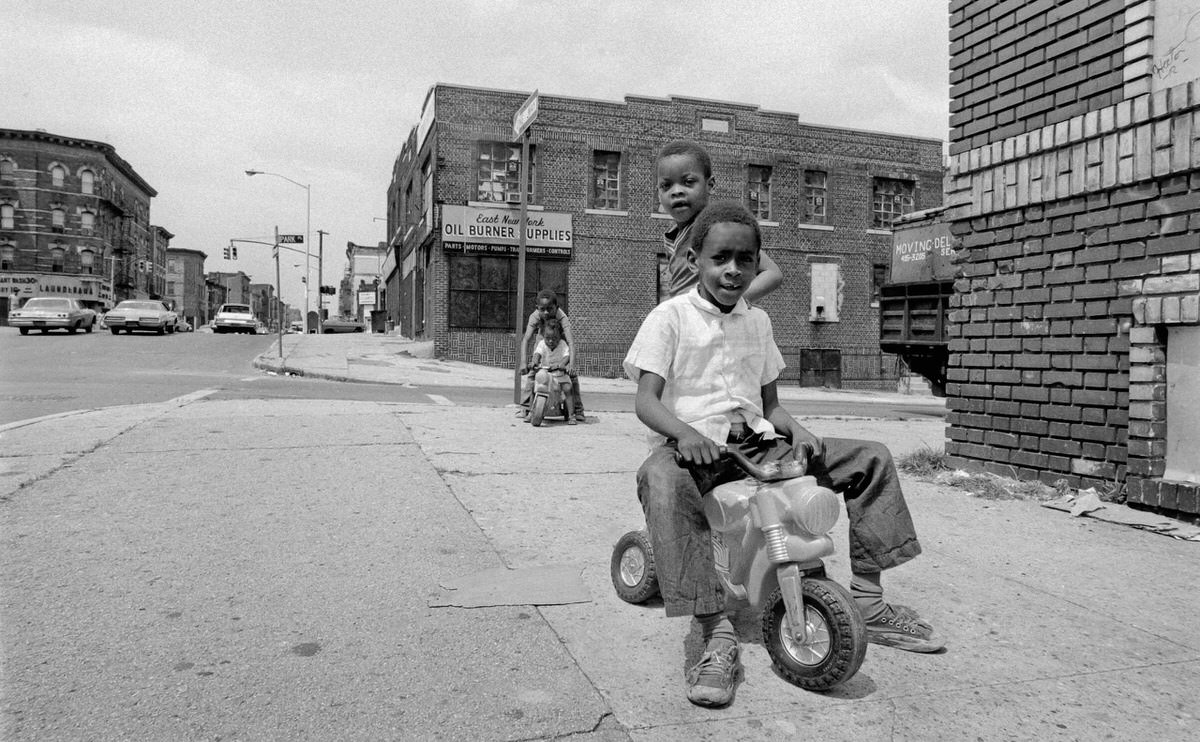

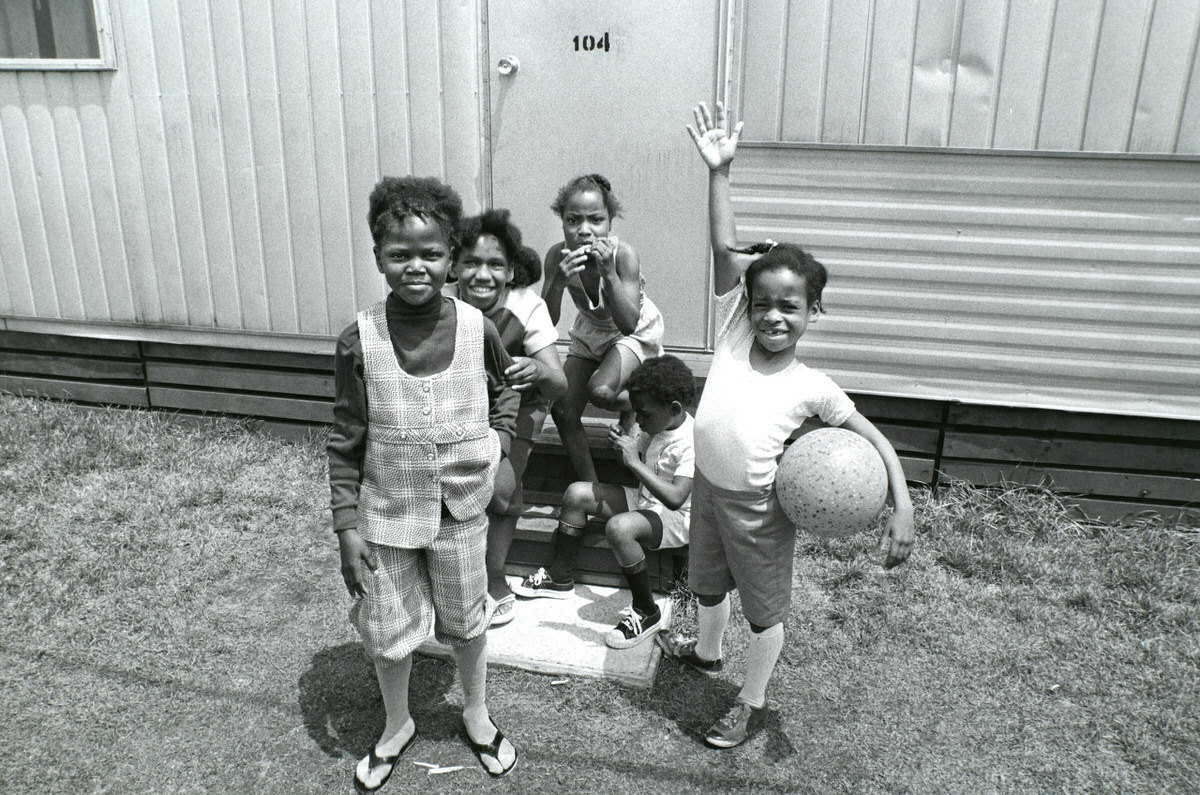

Despite the tough conditions, Brownsville had a strong sense of community. People knew each other. Families watched out for neighbors. Block associations formed to push back against crime and neglect. Community centers tried to offer after-school programs, sports, and meals for children. Churches played a major role. They provided food, clothing, and hope.

The 73rd Precinct, which served Brownsville, faced deep challenges. Officers were under-resourced and often mistrusted by the community. Tensions between police and residents were high. Complaints of abuse and neglect were frequent. At the same time, many officers feared walking the streets alone.

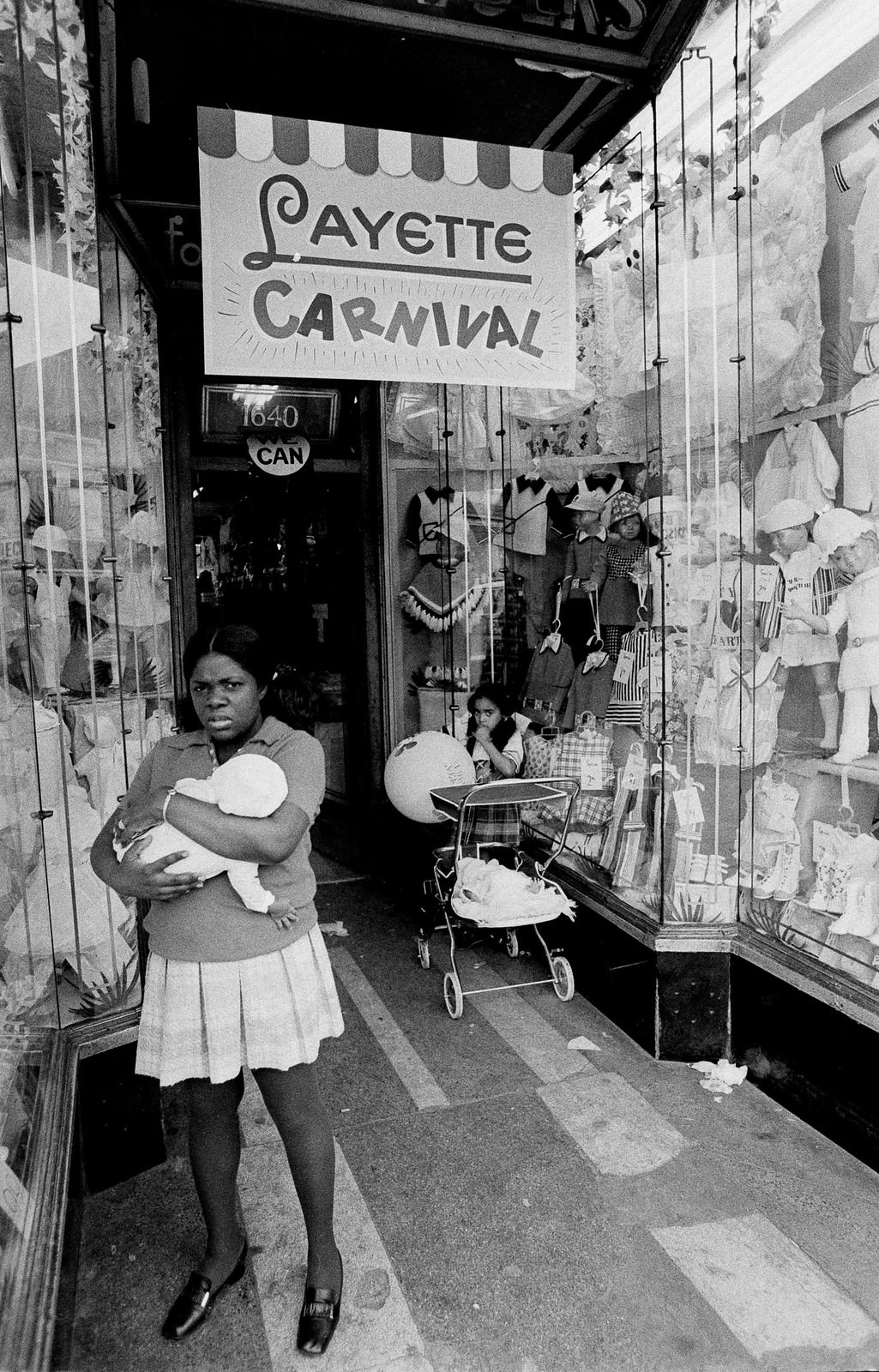

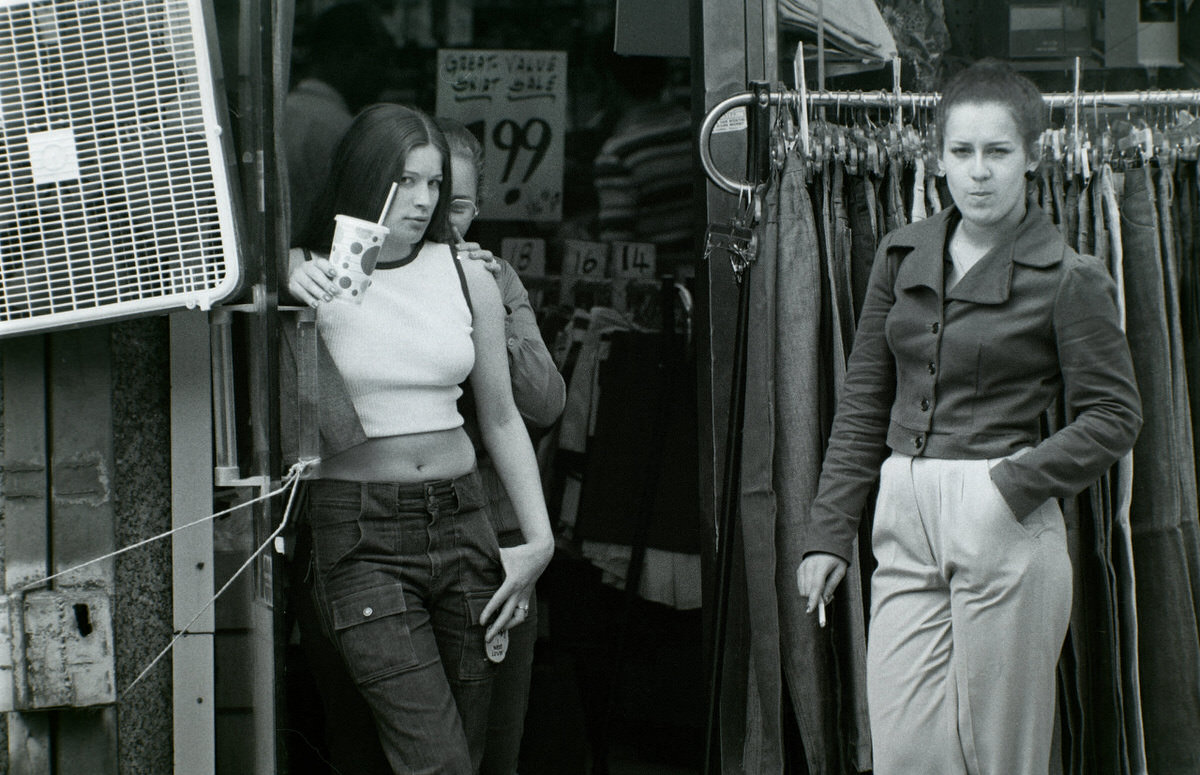

The economic situation added more pressure. Jobs were scarce. Many factories and warehouses that once provided employment had shut down or moved away. Local businesses struggled to survive. Young people saw few options beyond street hustling or informal work like fixing cars or selling goods on the sidewalk.

Health care access was limited. Clinics were understaffed, and hospitals were distant. The city’s financial crisis in the mid-1970s led to even more cuts. Mental health services were reduced. Social workers were overloaded. Children suffering from asthma, lead poisoning, and untreated infections were common.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings