At the turn of the 20th century, the Bronx was a borough of rapid transformation. New elevated train lines and the first subway routes opened up the landscape, bringing with them waves of new residents seeking space and opportunity beyond the crowded tenements of Manhattan. As farmland gave way to apartment buildings, and quiet villages expanded into bustling neighborhoods, a different kind of construction was also booming: the building of churches. For the diverse immigrant communities pouring into the Bronx, these new houses of worship were more than just places for Sunday services; they were the very cornerstones of their new lives.

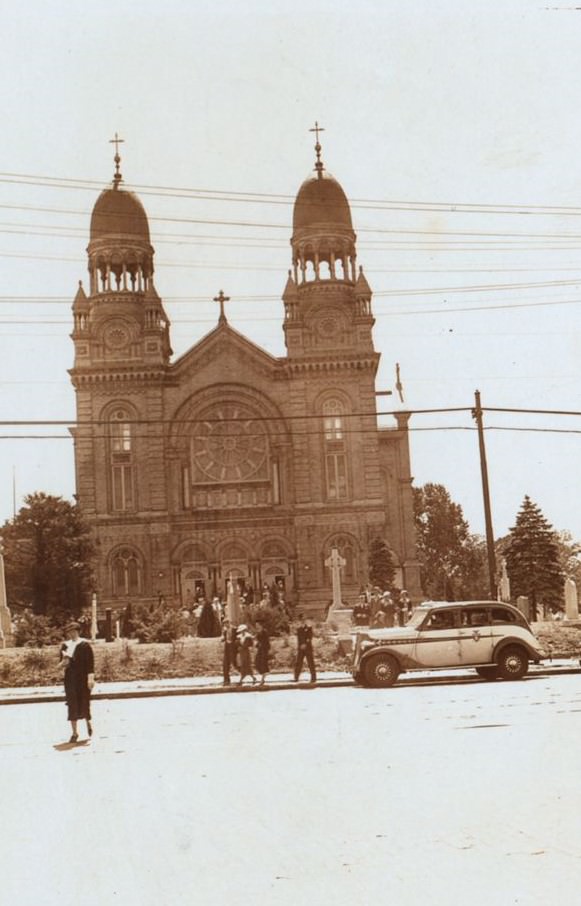

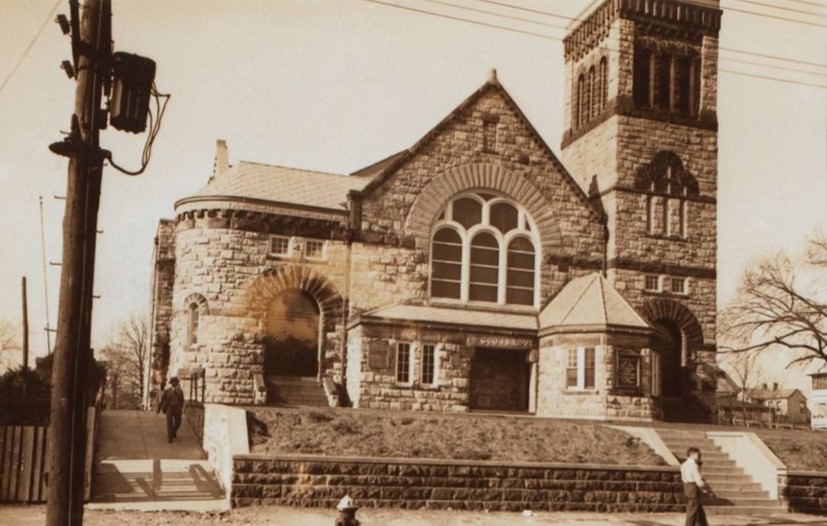

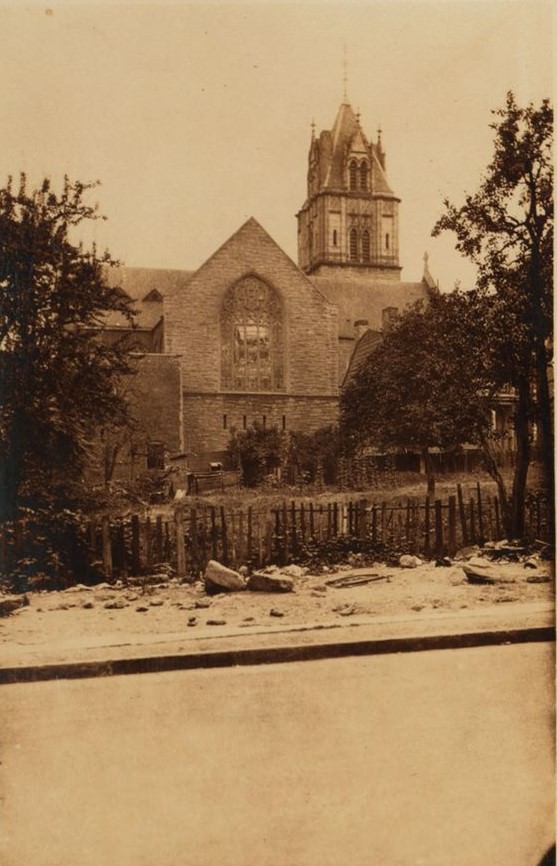

The architectural styles of these churches told the stories of the people who built them. In the South Bronx, the German Catholic community that had settled in Melrose erected the Church of the Immaculate Conception. Work on the present brick Romanesque Revival building began in 1887, and its soaring steeple became a prominent landmark. Sermons were delivered in both German and English, a common practice in a parish that initially catered to a predominantly German-speaking congregation. The church complex grew over the next two decades to include a large rectory and a school hall capable of seating 800 students, a testament to the community’s commitment to both faith and education.

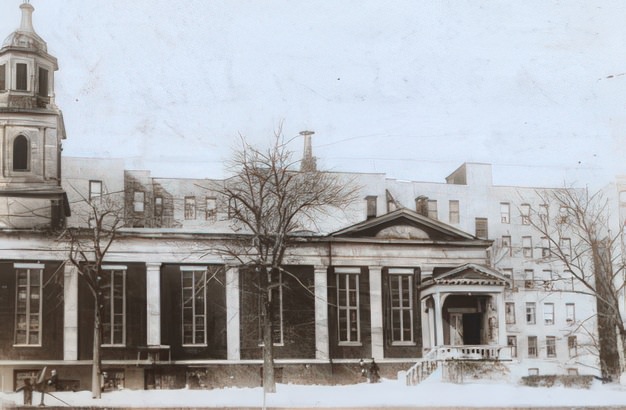

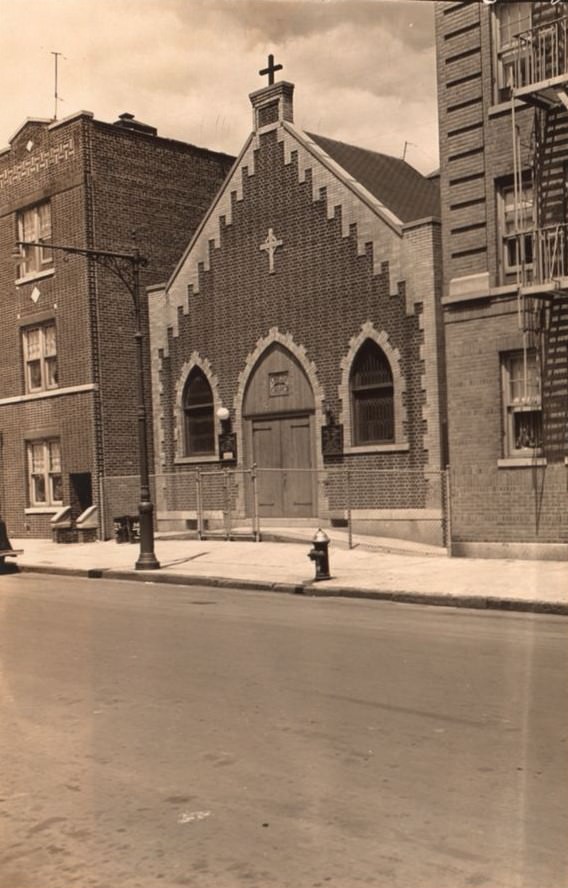

Nearby, in the Mott Haven section, St. Jerome’s Roman Catholic Church served the growing Irish and German immigrant populations. Established in 1869, the parish initially held masses in an abandoned market house. By the early 1900s, it had a dedicated school, St. Jerome’s Academy, which was staffed by the Ursuline sisters. The church became a hub of community life, offering not just schooling but also social clubs and activities that helped preserve cultural ties and forge new ones in a new land.

Read more

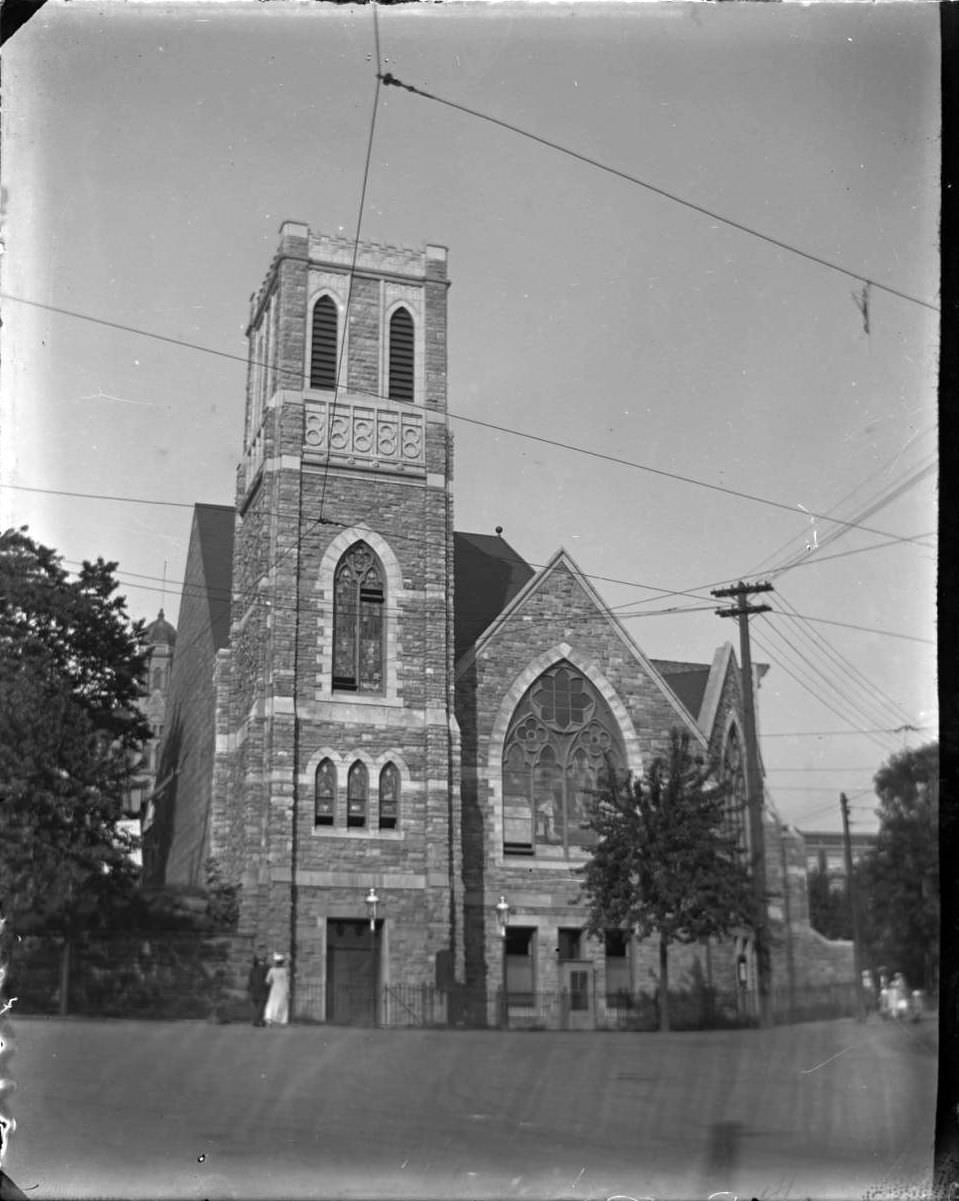

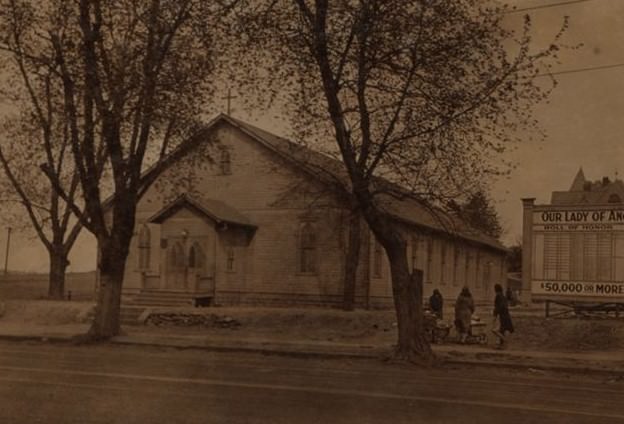

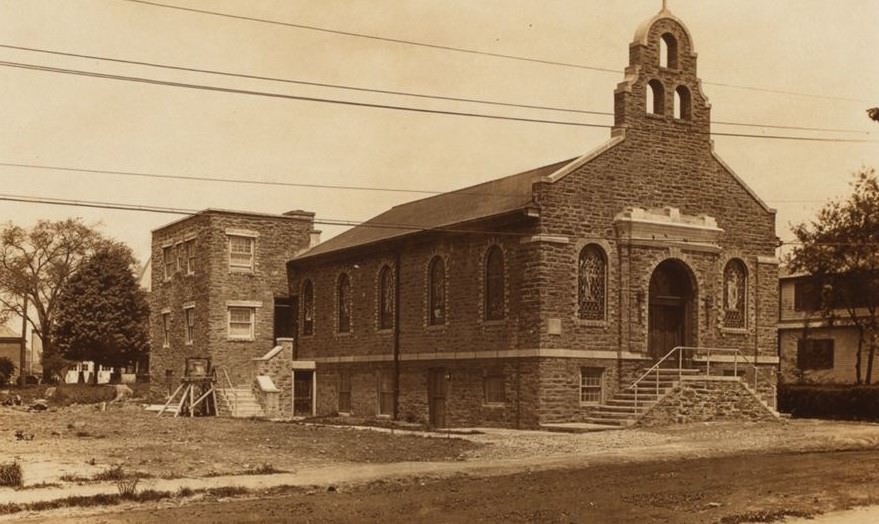

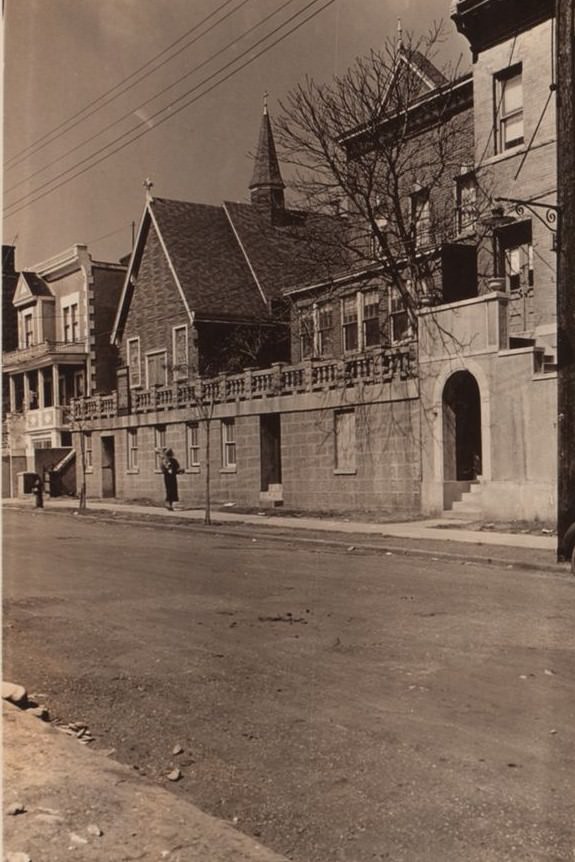

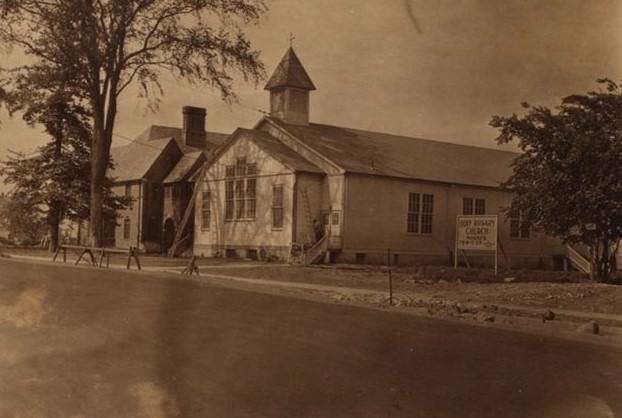

The influx of Italian immigrants also left its mark on the Bronx’s religious landscape. The men who worked on the Jerome Park Reservoir project, many of whom were of Italian descent, built St. Philip Neri Church with stone they quarried from the reservoir site after their long workdays. This act of devotion created a church that was quite literally built by the hands of its congregation. Over time, the parish would also welcome a large Irish-American population.

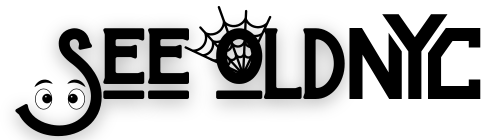

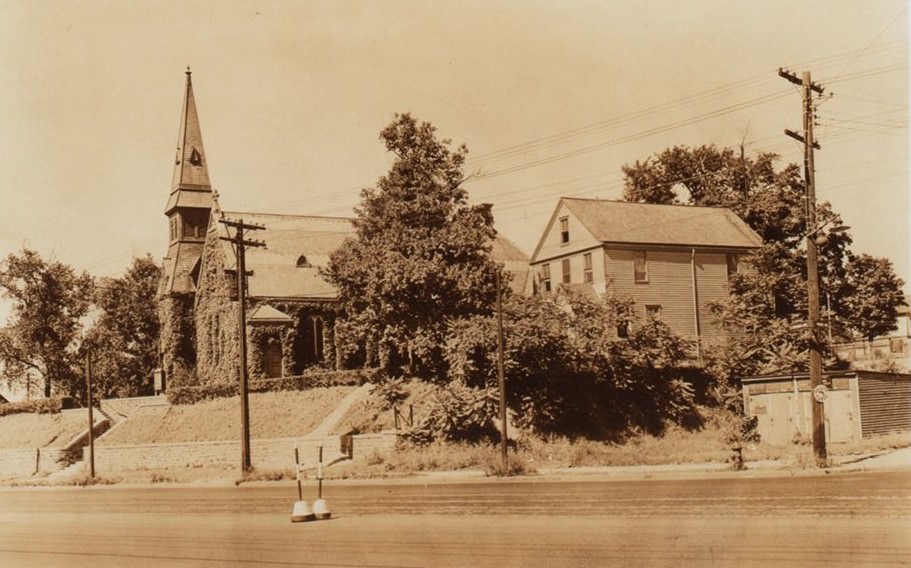

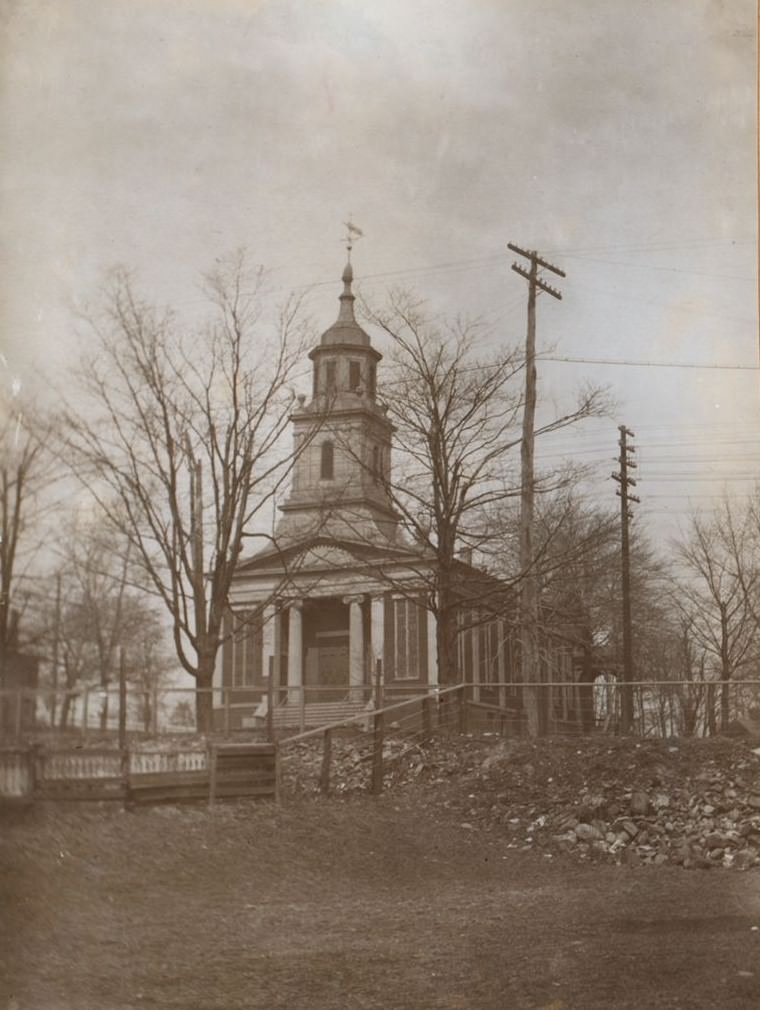

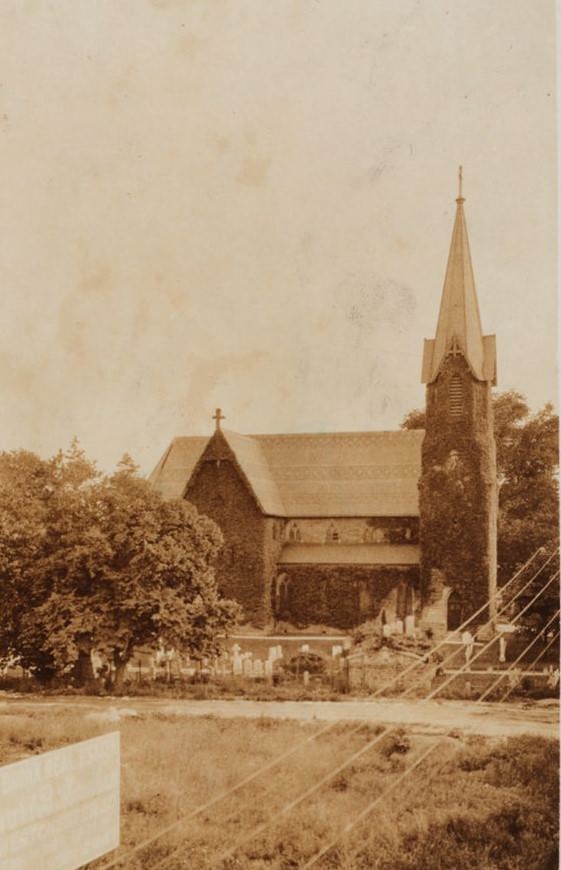

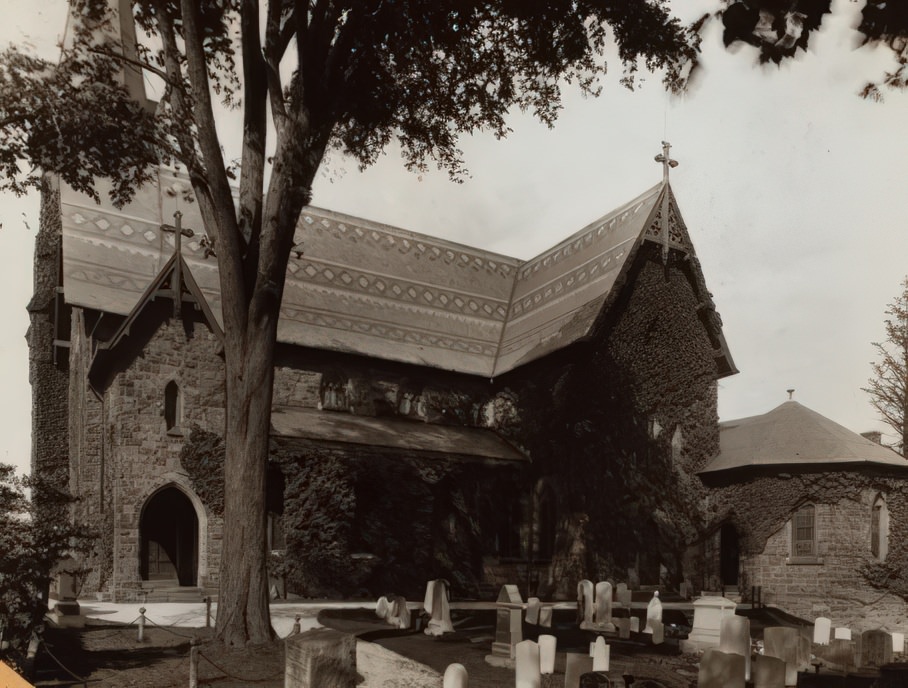

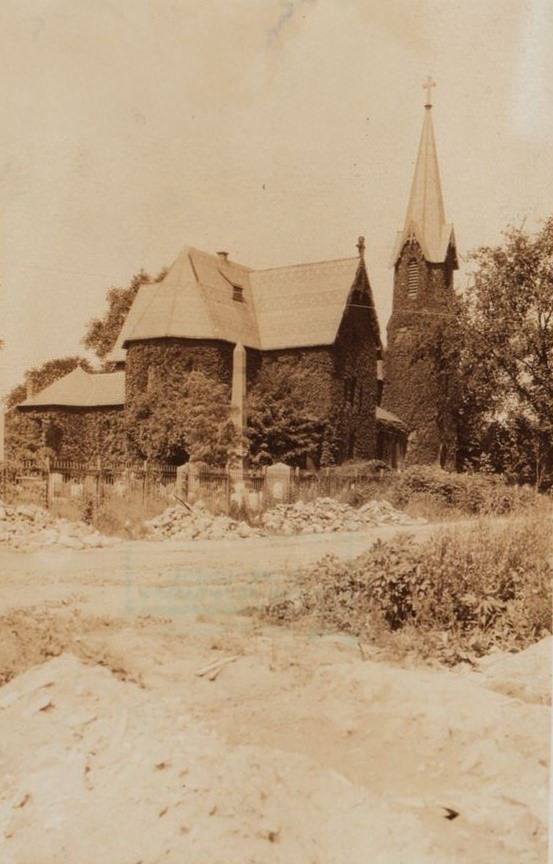

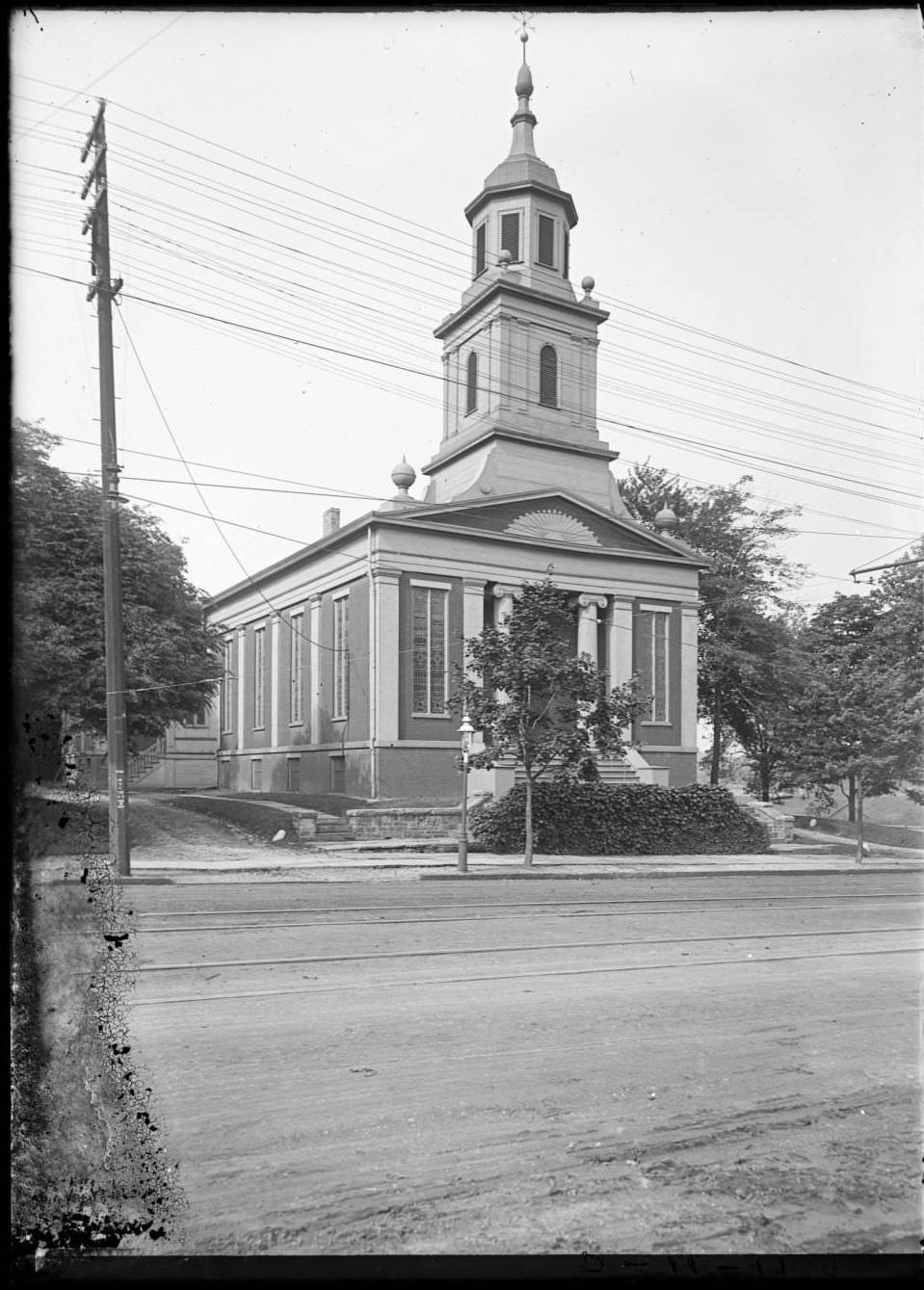

As one moved north, the denominations and architectural styles reflected different settlement patterns. The Fordham Manor Reformed Church, with roots stretching back to 1696, represented one of the earliest Dutch congregations in the Bronx. While their original 18th-century structure was long gone, the congregation erected a new church building in the early 1900s, continuing its long history in the area. This church served a more established, less recent immigrant community, and its presence spoke to the deep colonial roots of the borough.

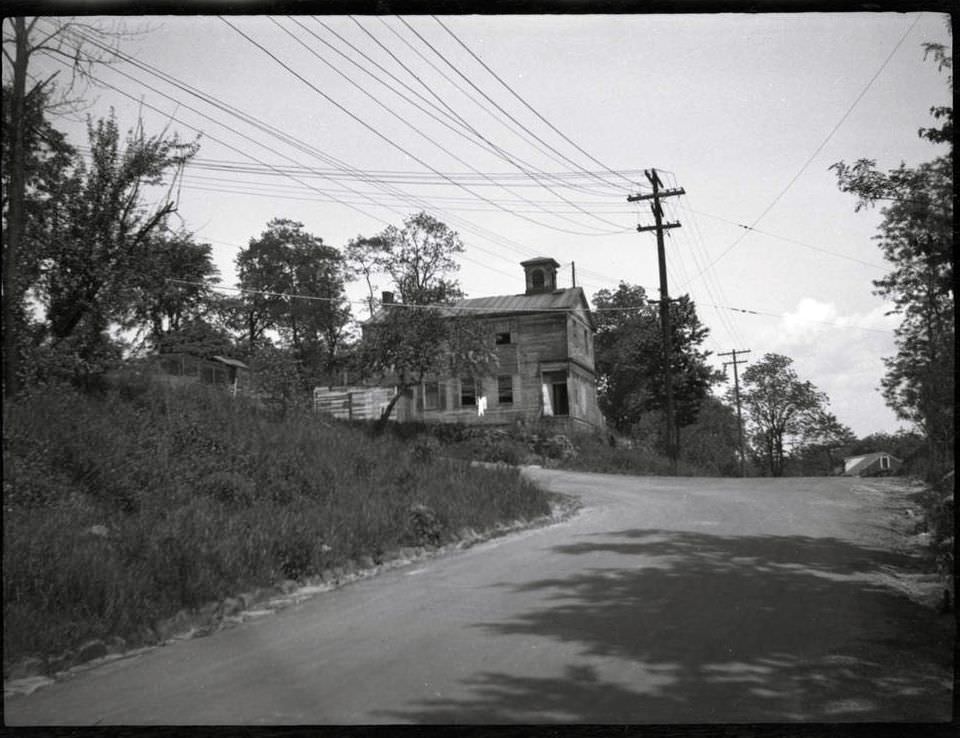

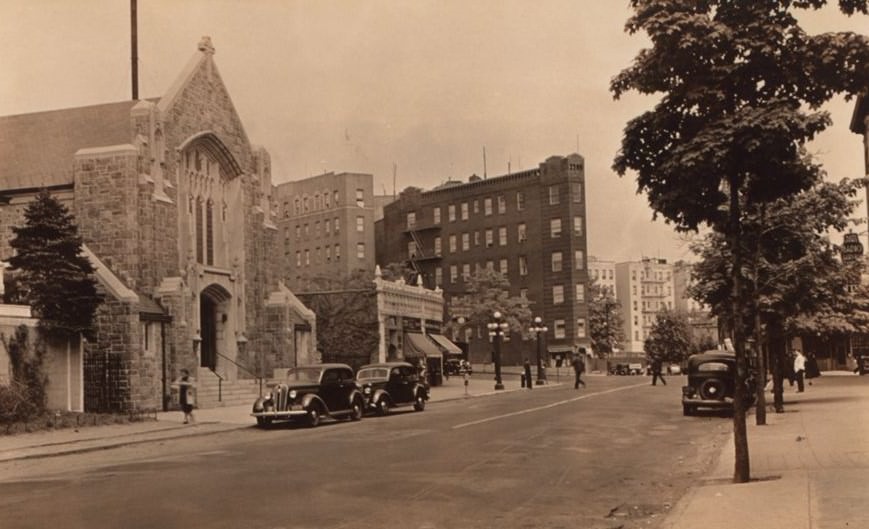

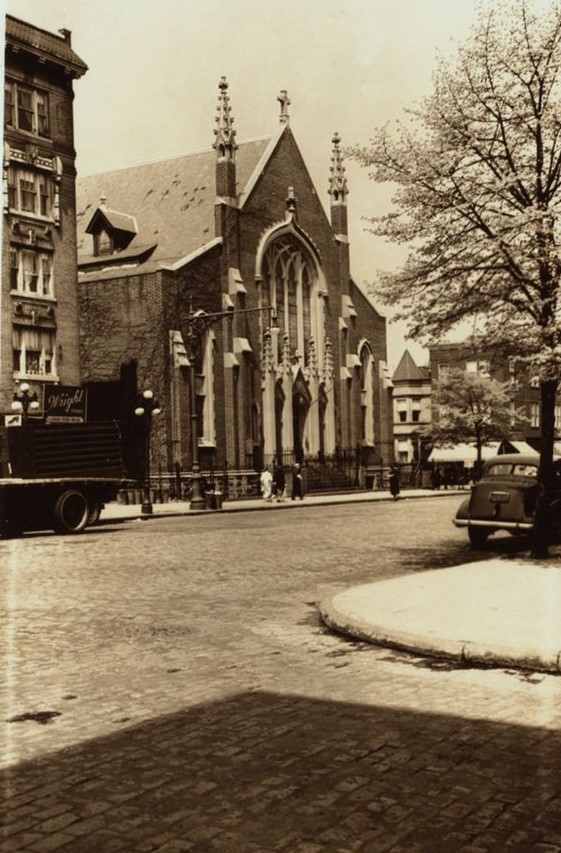

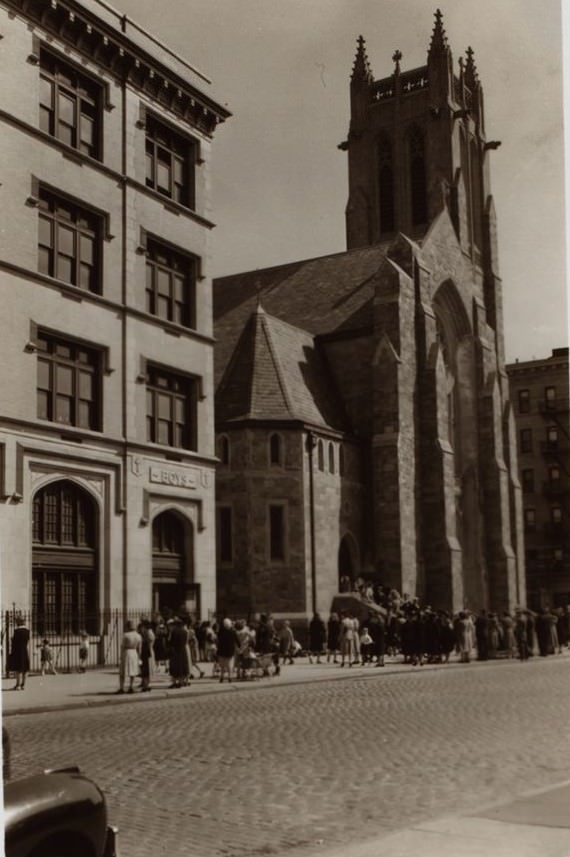

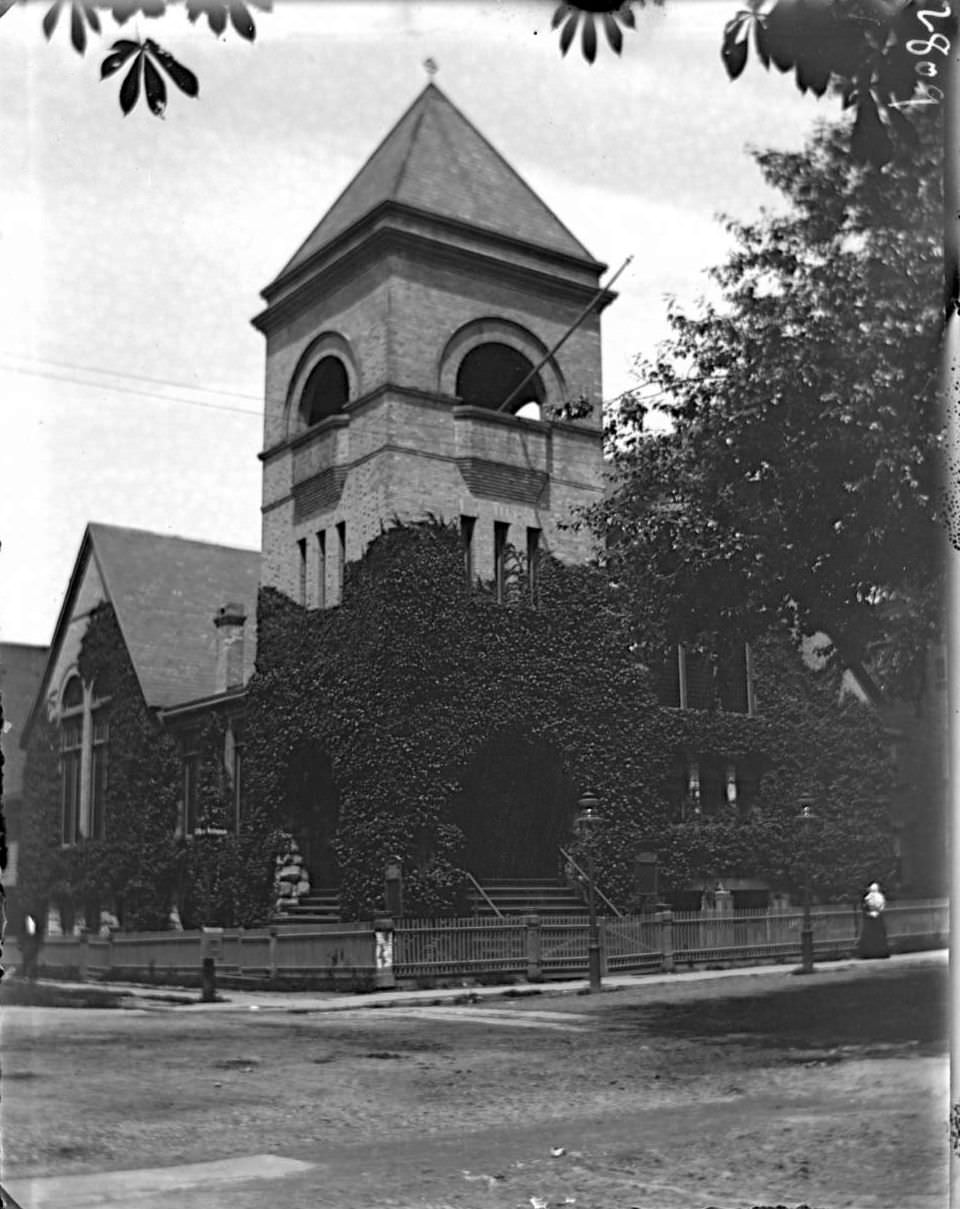

In the Morrisania neighborhood, St. Augustine’s Roman Catholic Church stood as a grand edifice. Though the parish was established in 1849 by Irish immigrants, the current, larger church was built in 1894 after a fire destroyed the previous structure. Its design was a mix of European styles, with tall, narrow Gothic-style windows and a rusticated stone facing reminiscent of the Renaissance. This church served a mixed congregation of Irish and German Catholics and was the setting for significant community events, including the 1900 wedding of a young Al Smith, who would later become the governor of New York.

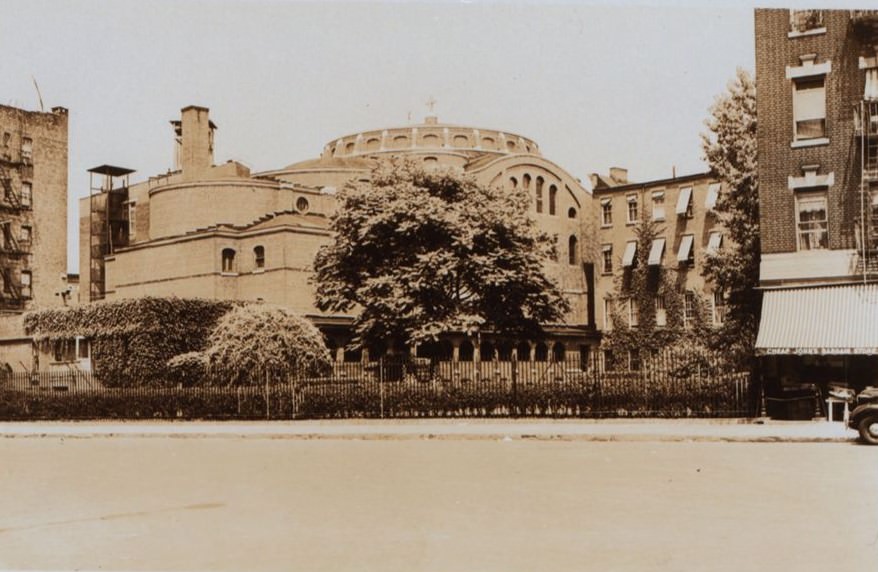

The early 1900s also saw the establishment of St. Anselm’s Church in the Mott Haven neighborhood. Founded in 1891 to serve the German Catholic community, the parish was entrusted to Benedictine monks. The present church, built in 1918, is a striking example of Byzantine Revival architecture, its design inspired by the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. The interior featured intricate mosaics and frescoes, creating a space of artistic and spiritual significance. The parish also sponsored a Fife and Drum Corps for the community’s youth, an example of the many ways churches provided structured activities for children.

Beyond their religious functions, these churches were vital social service providers. Many operated parochial schools that offered education to thousands of children, often in their native languages as well as English. They organized benevolent societies to assist families in need, providing everything from food and coal to temporary shelter. For new arrivals, the church was often the first point of contact for finding work, housing, and a sense of community. Social events, from festivals and bazaars to dances and plays, were held in church halls, providing entertainment and a place for neighbors to connect. These institutions were the glue that held many of these burgeoning neighborhoods together, offering a sense of stability and identity in a rapidly changing world.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings