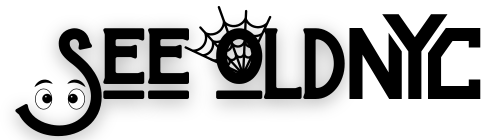

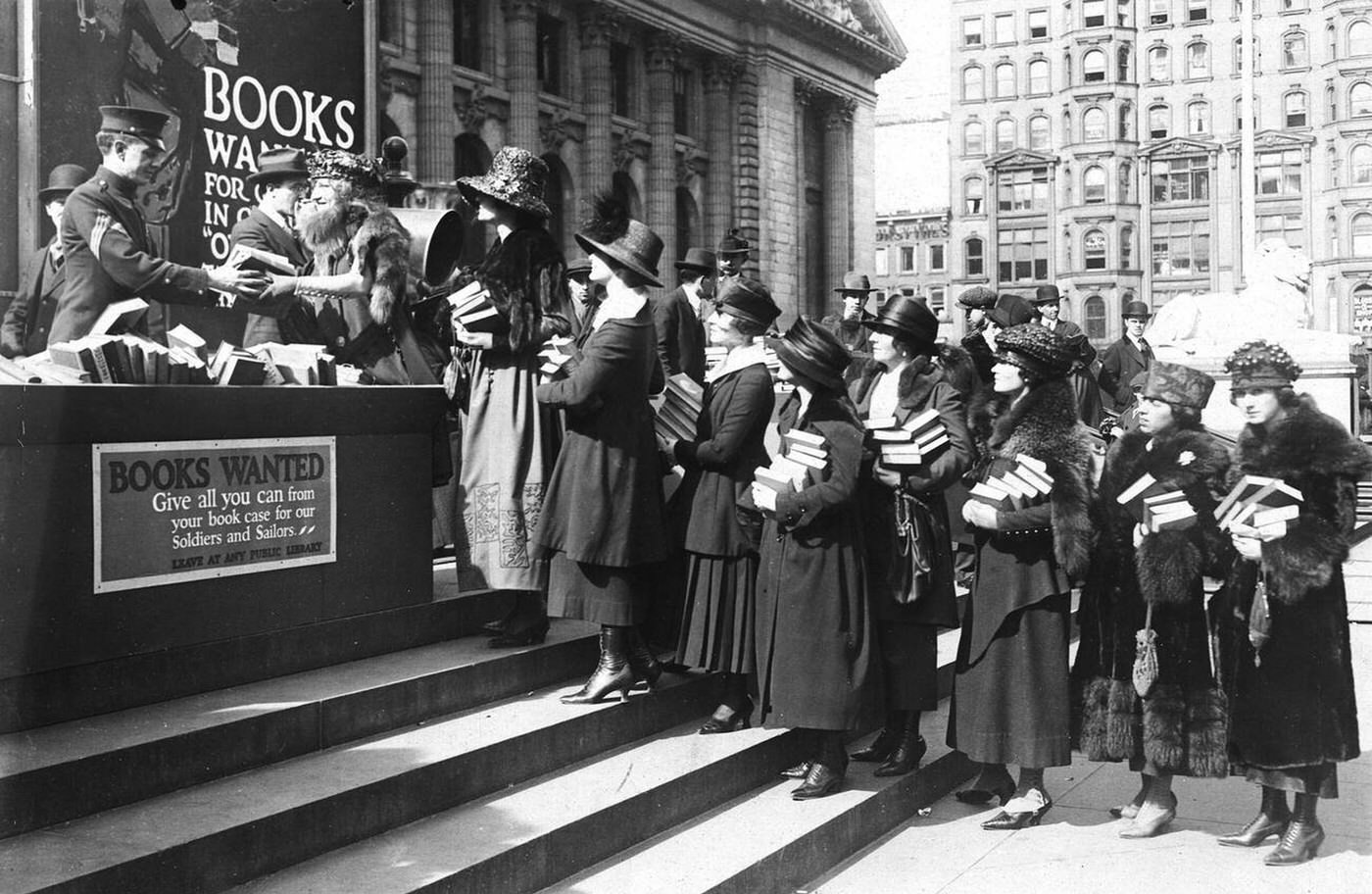

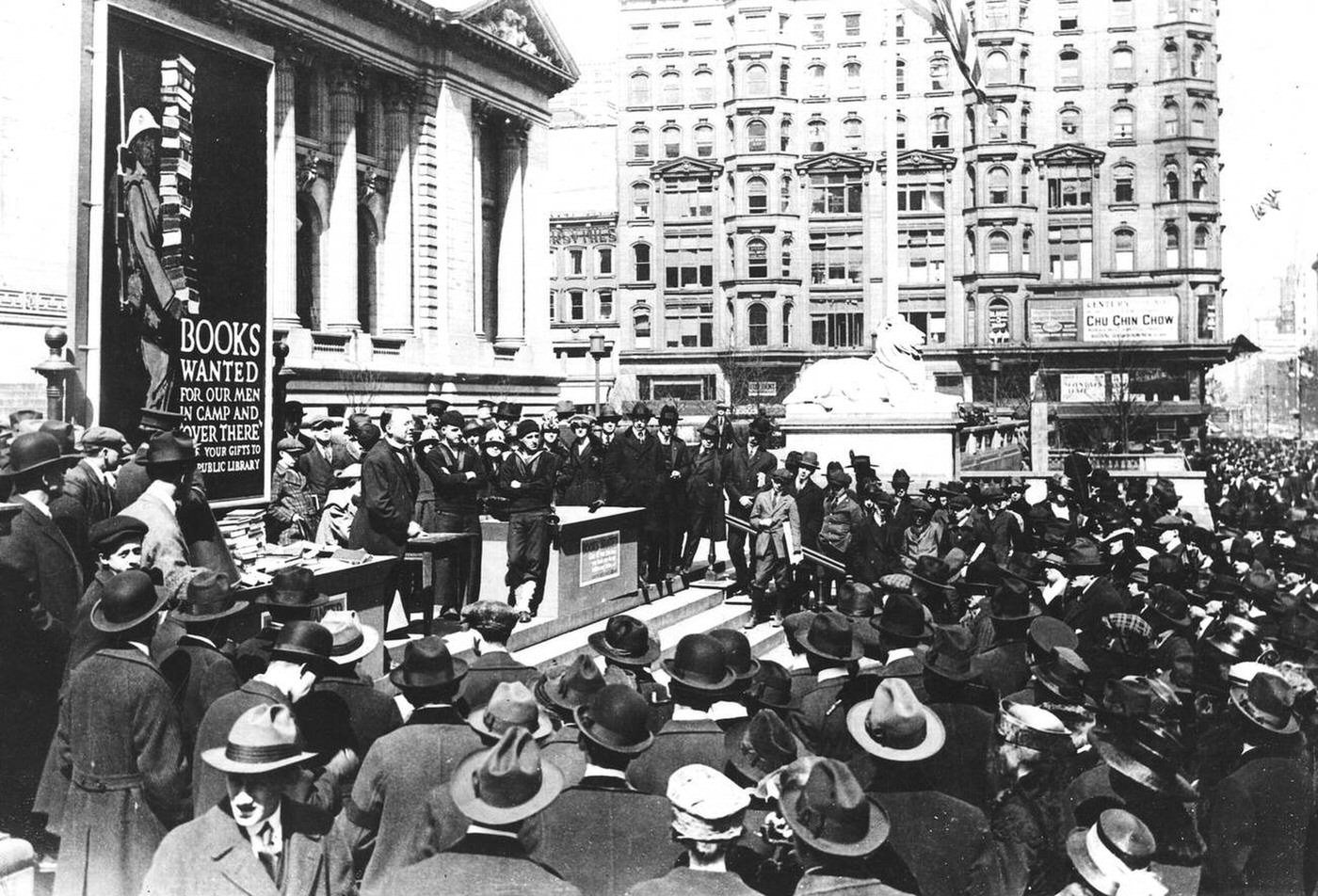

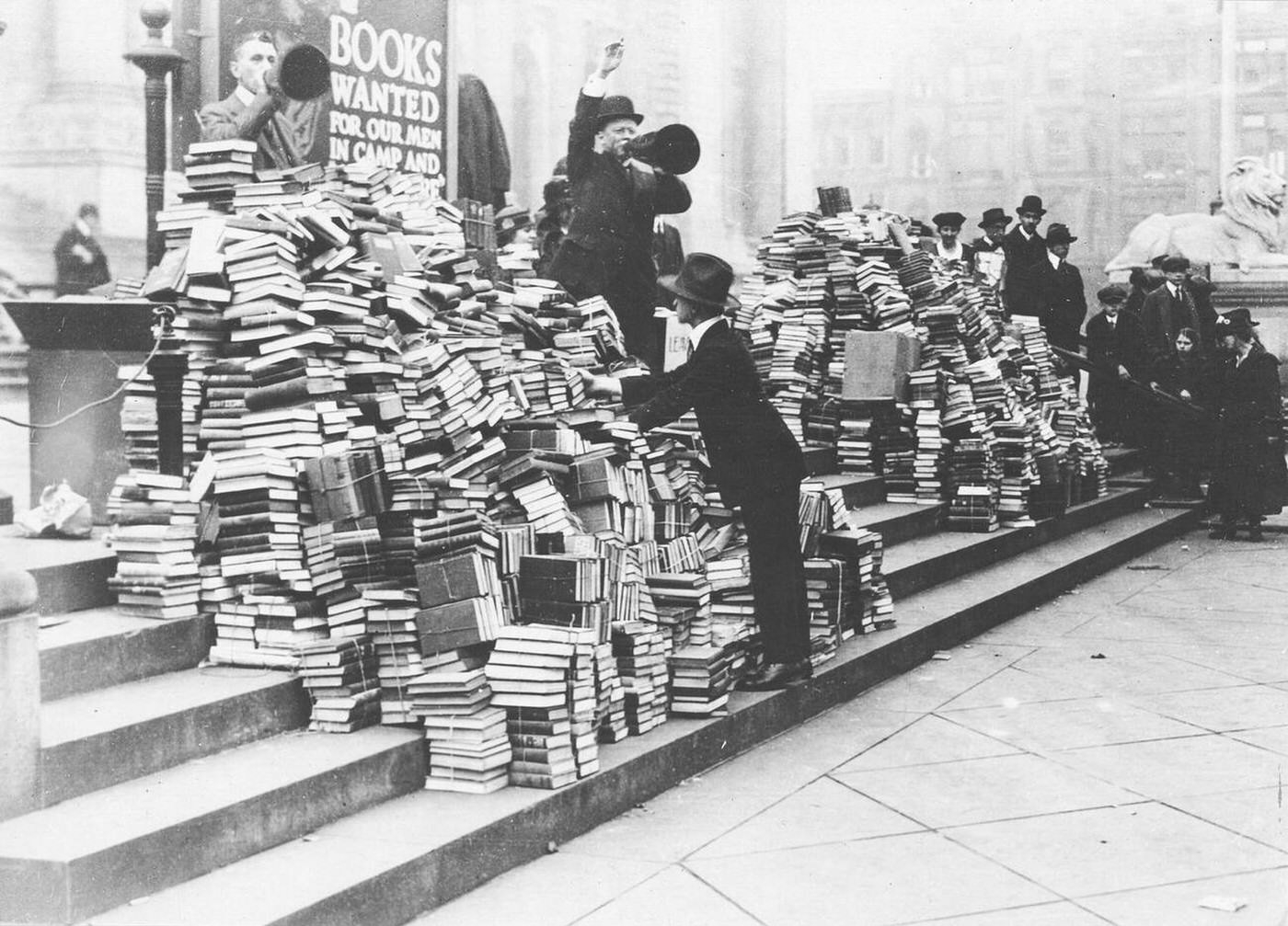

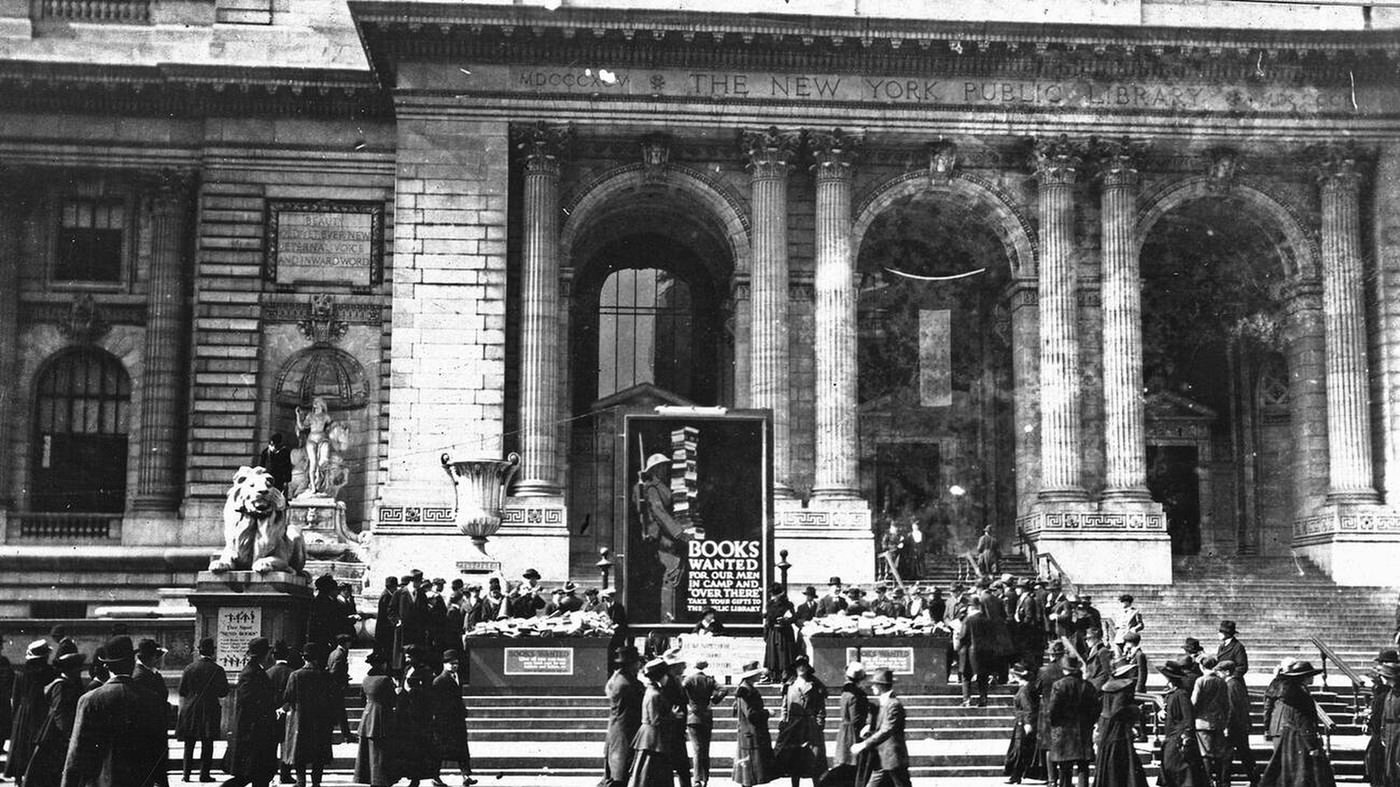

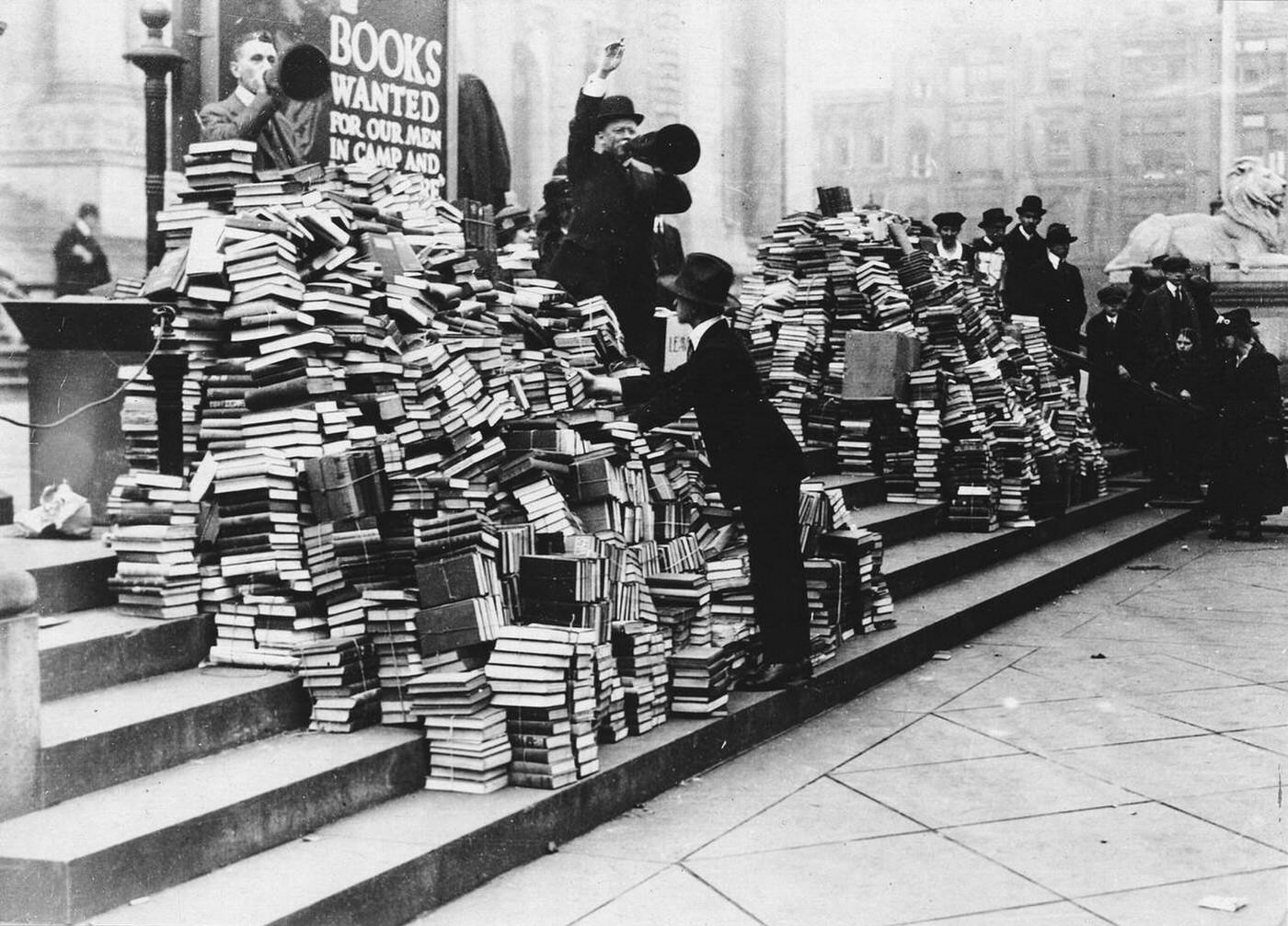

In the fall of 1918, the front steps of the New York Public Library became the center of a national effort to supply reading materials to American soldiers serving in World War I. The American Library Association (ALA) launched a massive campaign to collect books and raise money for the war’s Library War Service. The goal was direct and urgent: provide soldiers and sailors with books for education, comfort, and distraction during wartime.

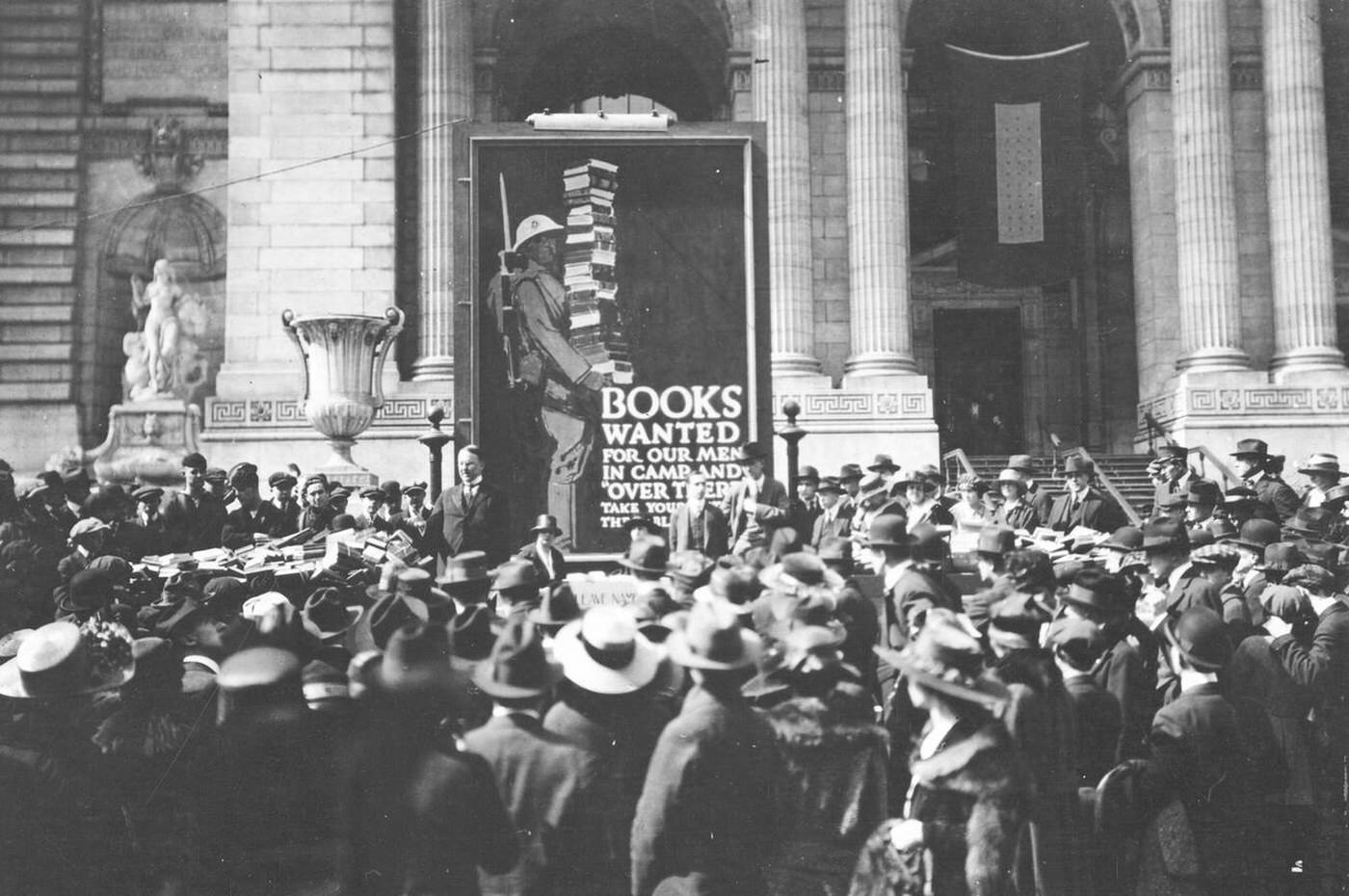

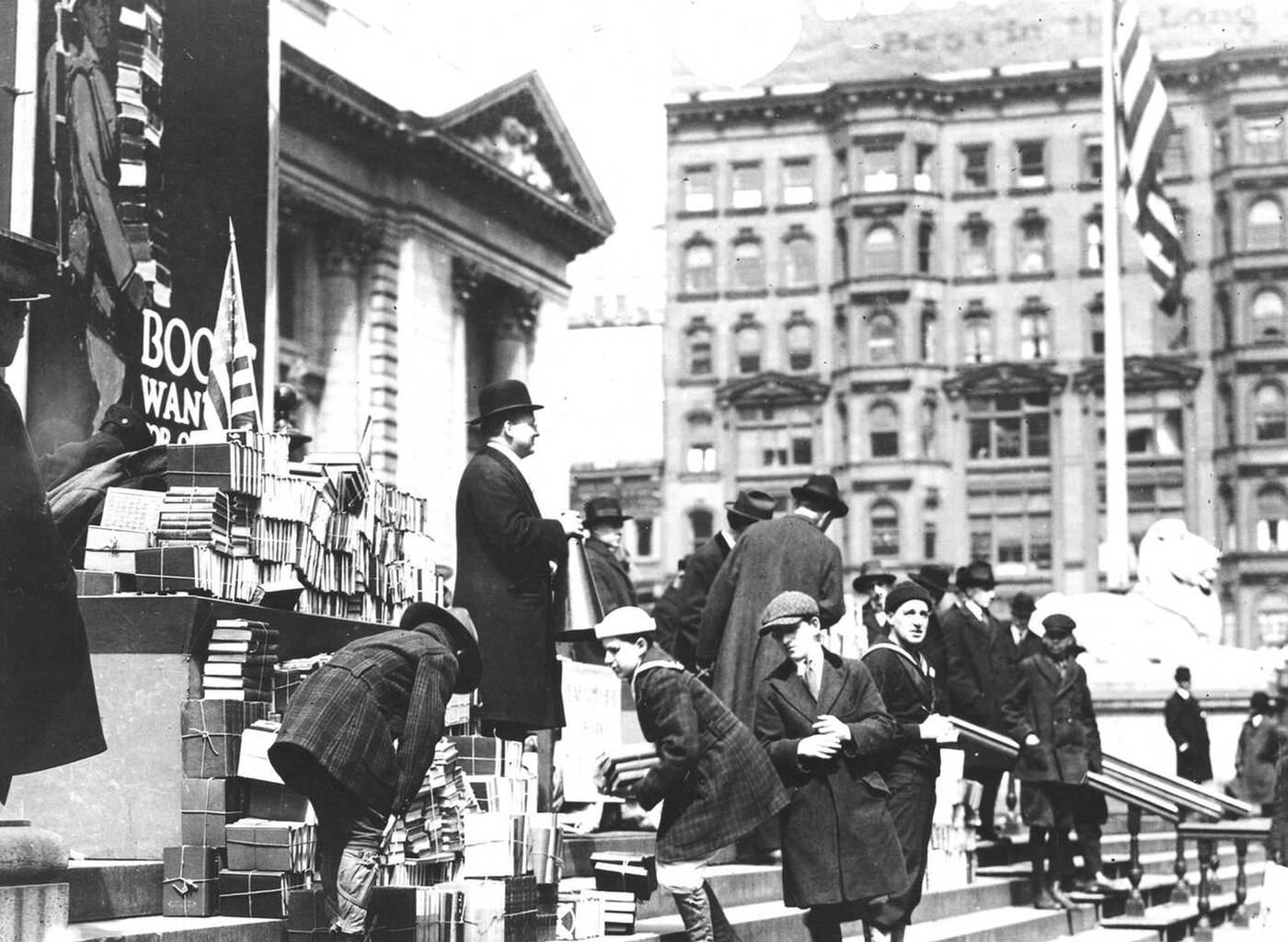

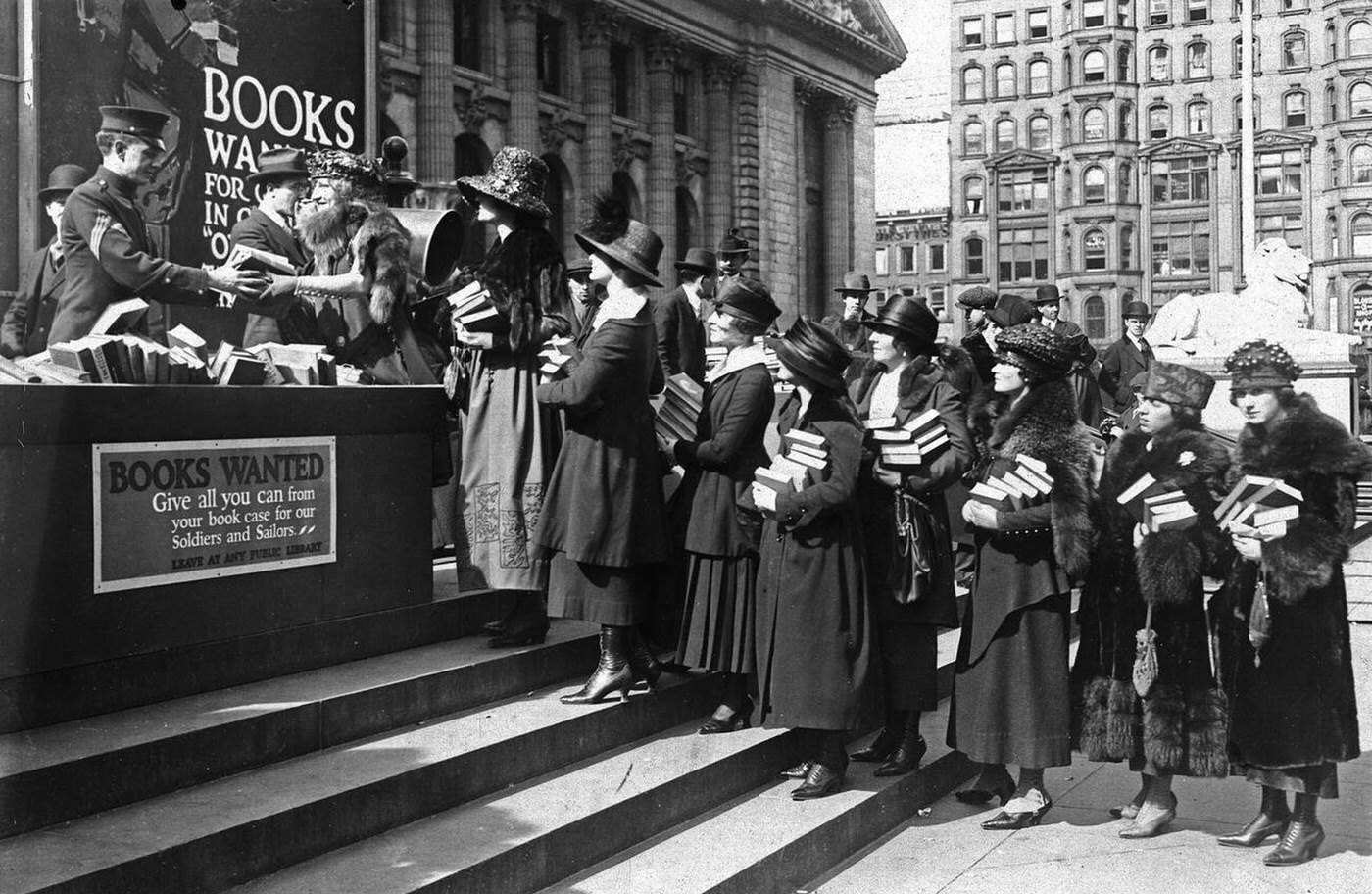

Large banners hung across the library’s marble facade on Fifth Avenue, calling citizens to donate books for the troops. Tables lined the front steps, staffed by volunteers—mostly women, students, and librarians—who sorted, labeled, and boxed donations as they arrived. New Yorkers arrived throughout the day carrying stacks of novels, dictionaries, and technical manuals. Many brought books wrapped in brown paper, with handwritten notes inside for the men overseas.

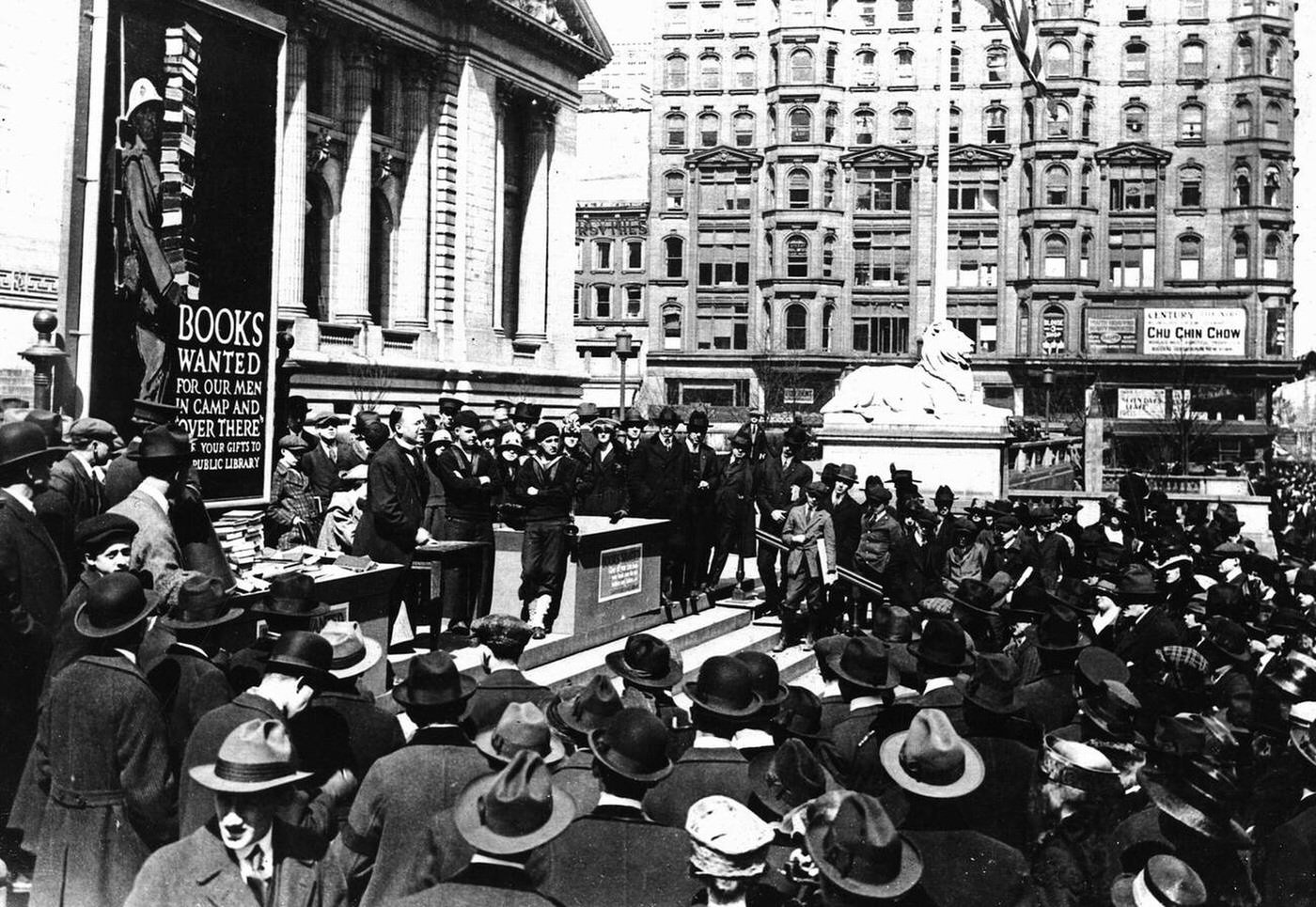

The campaign was part of a larger national drive led by the ALA with support from the War Department and the Red Cross. Across the country, libraries and bookstores became collection points. In New York, the location in front of the main library symbolized the city’s cultural and civic strength. Posters around the city carried slogans such as “Books for Every Fighting Man” and “Help Win the War with Books.”

Read more

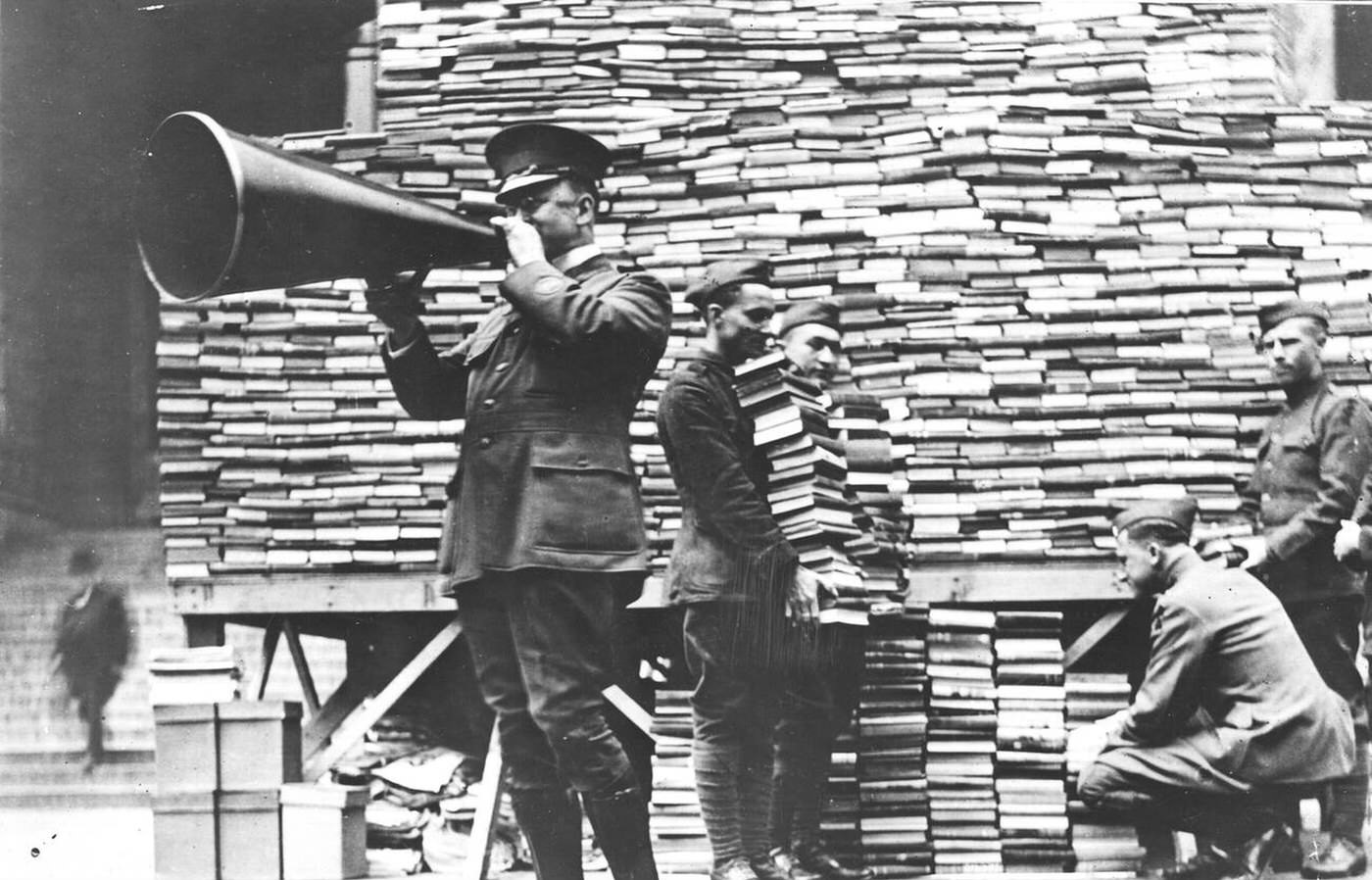

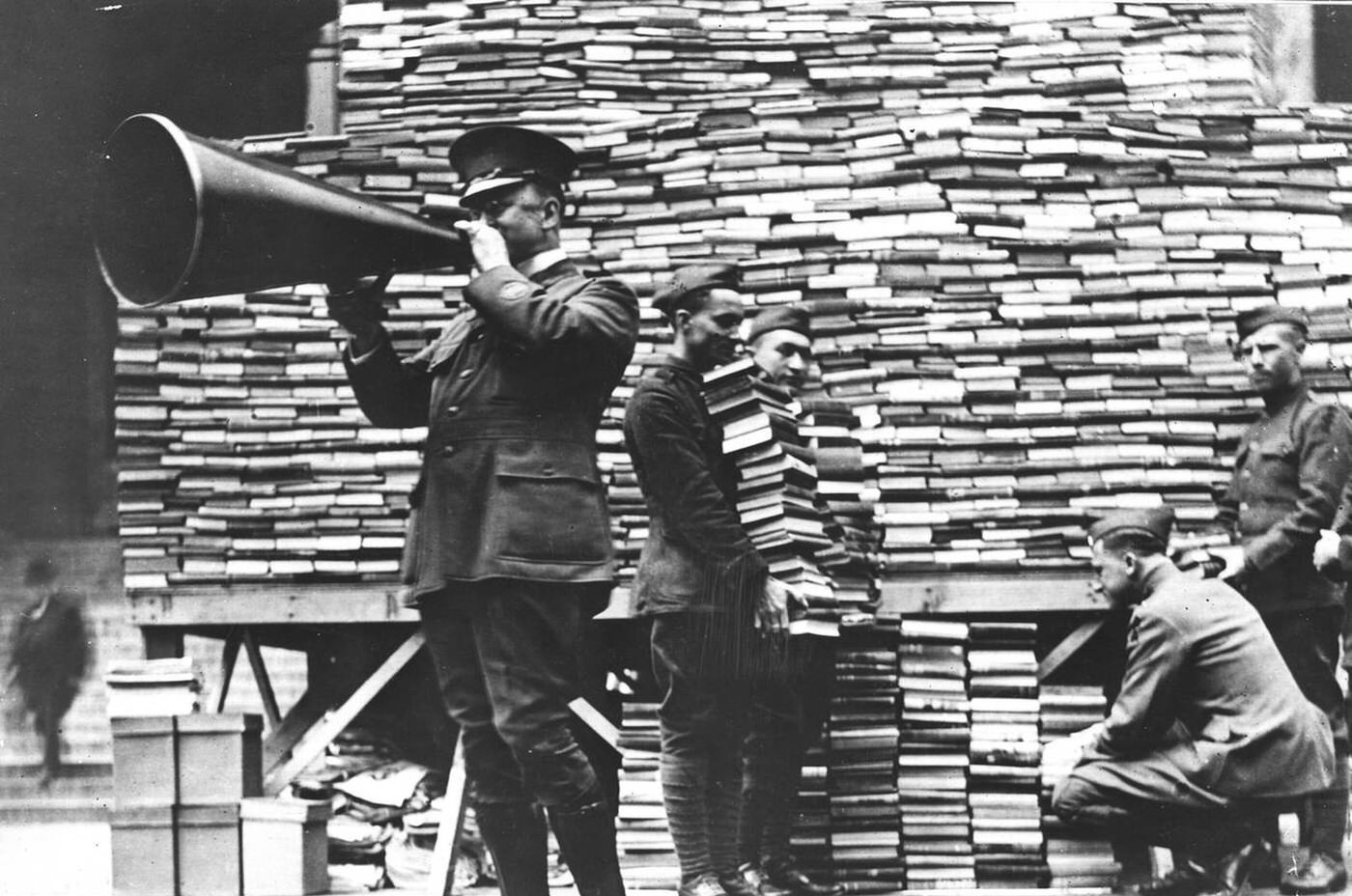

During the event, the library steps filled with activity. Soldiers on leave stood beside librarians in uniform, helping load crates onto wagons. The donated books were sent to special libraries the ALA had built at training camps and overseas bases. These camp libraries held everything from popular fiction to textbooks on mechanics, signaling equipment, and foreign languages.

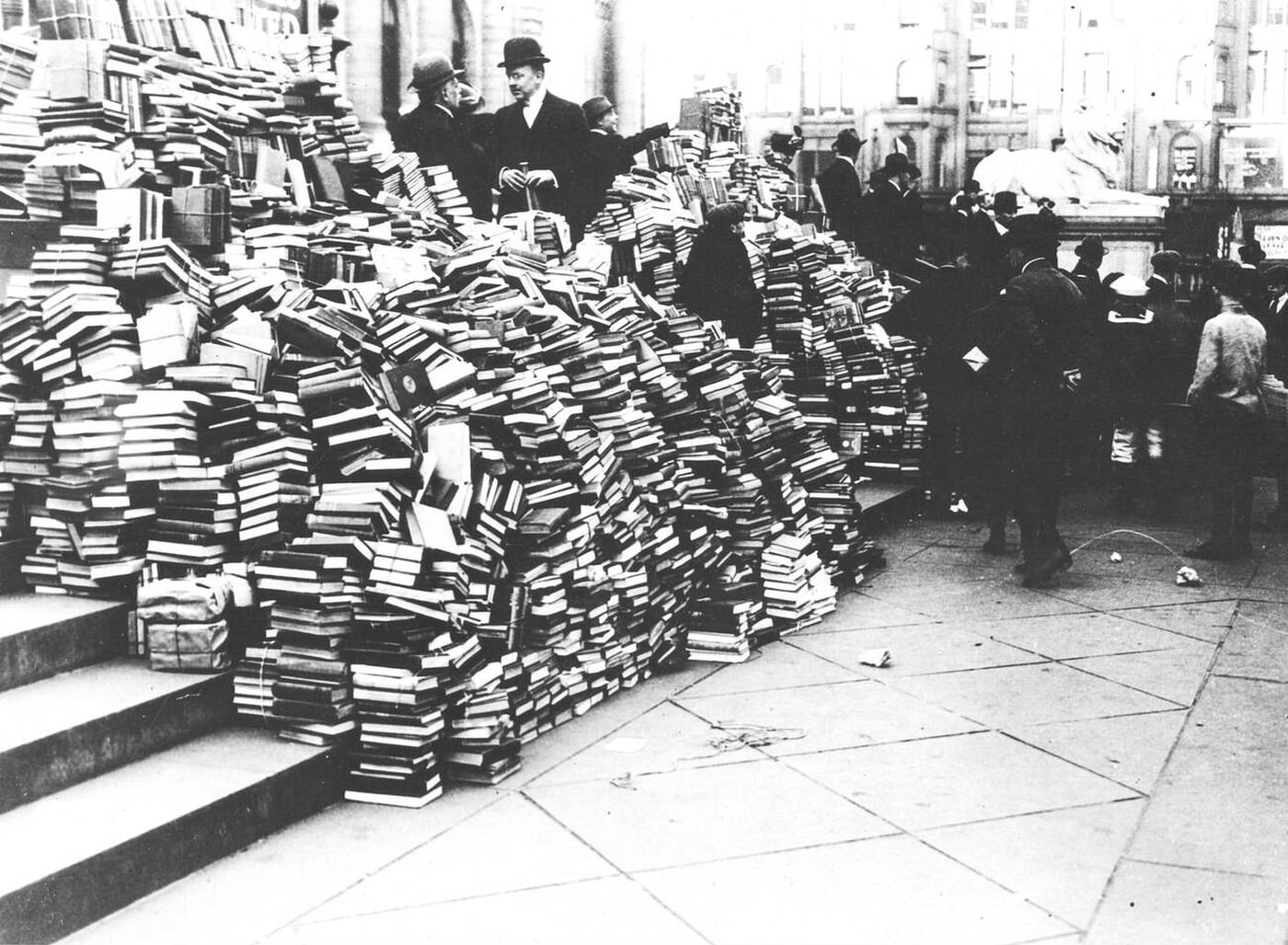

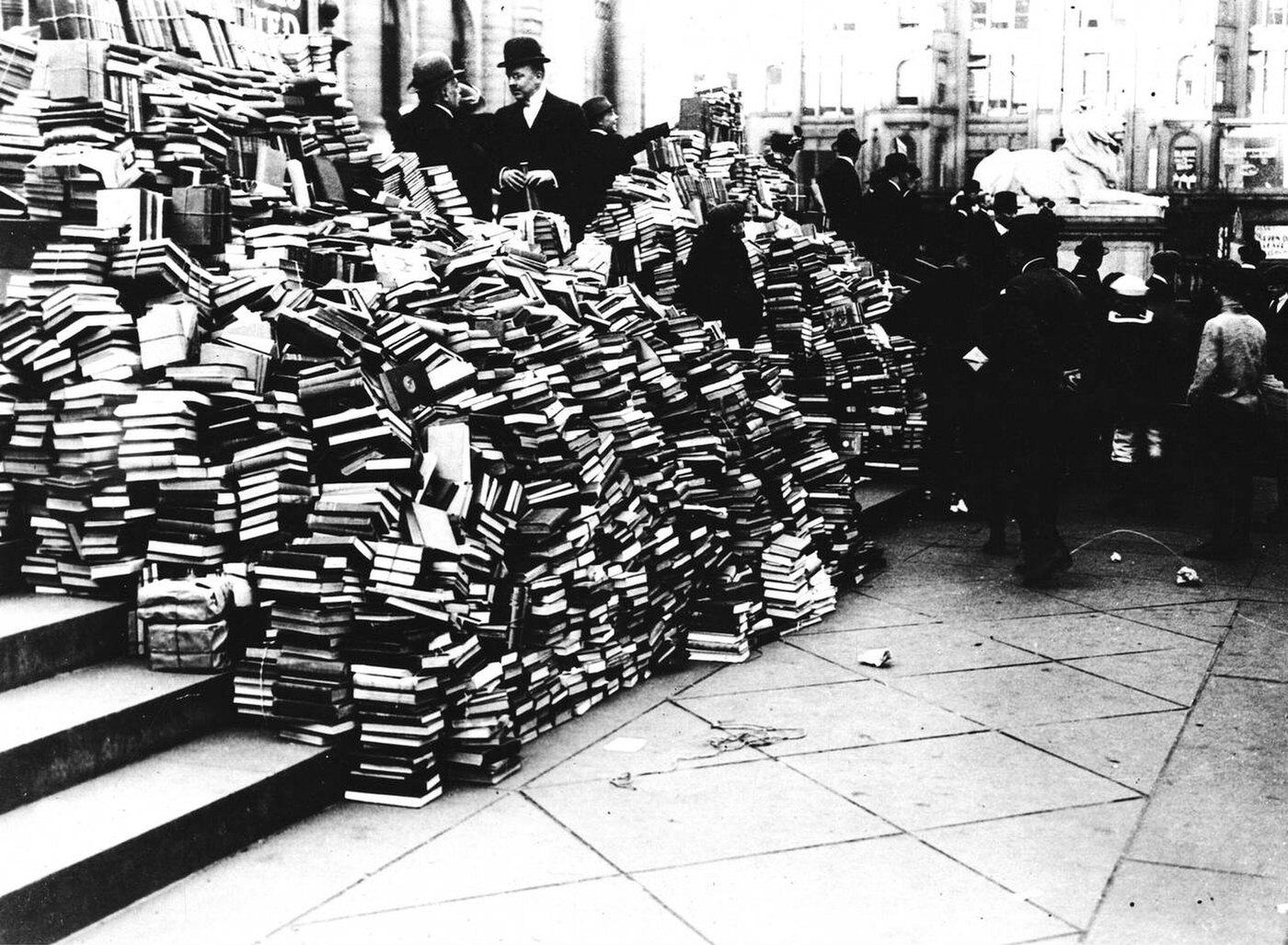

The ALA estimated that New Yorkers contributed tens of thousands of volumes during the campaign. Many books came from private collections and school libraries. Publishers also supplied new titles in bulk, while students gathered used books from homes and offices. Volunteers checked each book to ensure it was in usable condition and marked it with an ALA stamp before shipping.

The event in front of the New York Public Library lasted several days and drew large crowds. Newspapers reported long lines of donors and steady wagonloads of books departing for warehouses. Musicians played military tunes, and public officials stopped by to speak in support of the effort. The city’s participation reflected both patriotic duty and a belief in the value of reading as part of morale and recovery.

By the end of the 1918 campaign, the ALA had gathered millions of books nationwide. The New York Public Library drive became one of its most visible moments. For many citizens, dropping off a book on those steps was a way to take part in the war effort, sending a piece of home to men stationed far away.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings