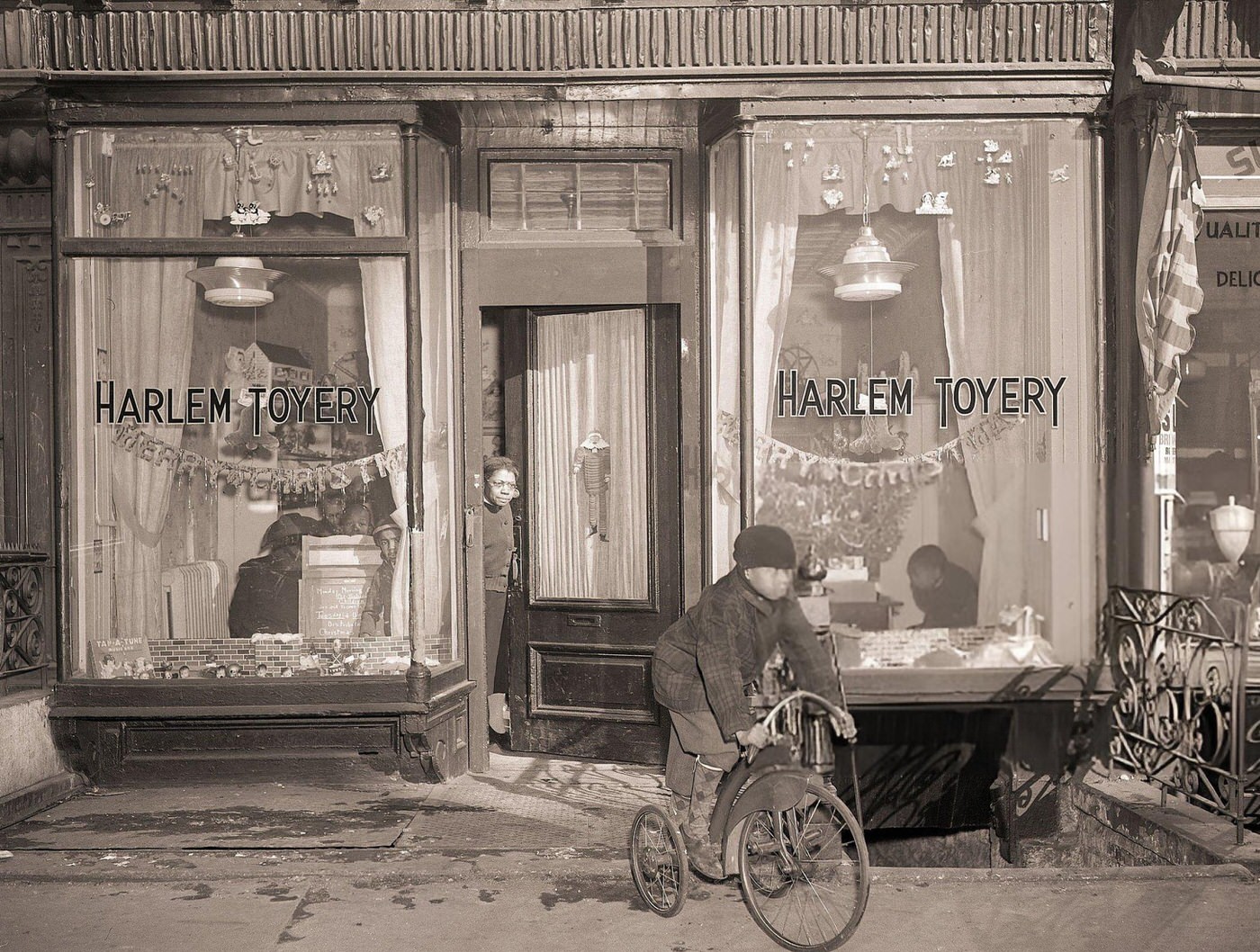

Harlem entered the 1940s as a vital center of Black life in America. Decades of migration, especially the Great Migration from the South, had swelled its population. By 1930, over 325,000 African Americans called Harlem home, creating a vibrant “city within a city”. Yet, the cultural excitement of the earlier Harlem Renaissance had given way to the economic hardships of the Great Depression. The Depression hit Harlem hard. Across northern cities like New York, Black unemployment soared past 50 percent, far higher than the rate for white workers. African Americans often found themselves the “last hired, first fired”. Government relief programs existed, but aid was often distributed unfairly by white officials, leaving many struggling. In response, community pillars like churches and social organizations stepped up to help neighbors survive.

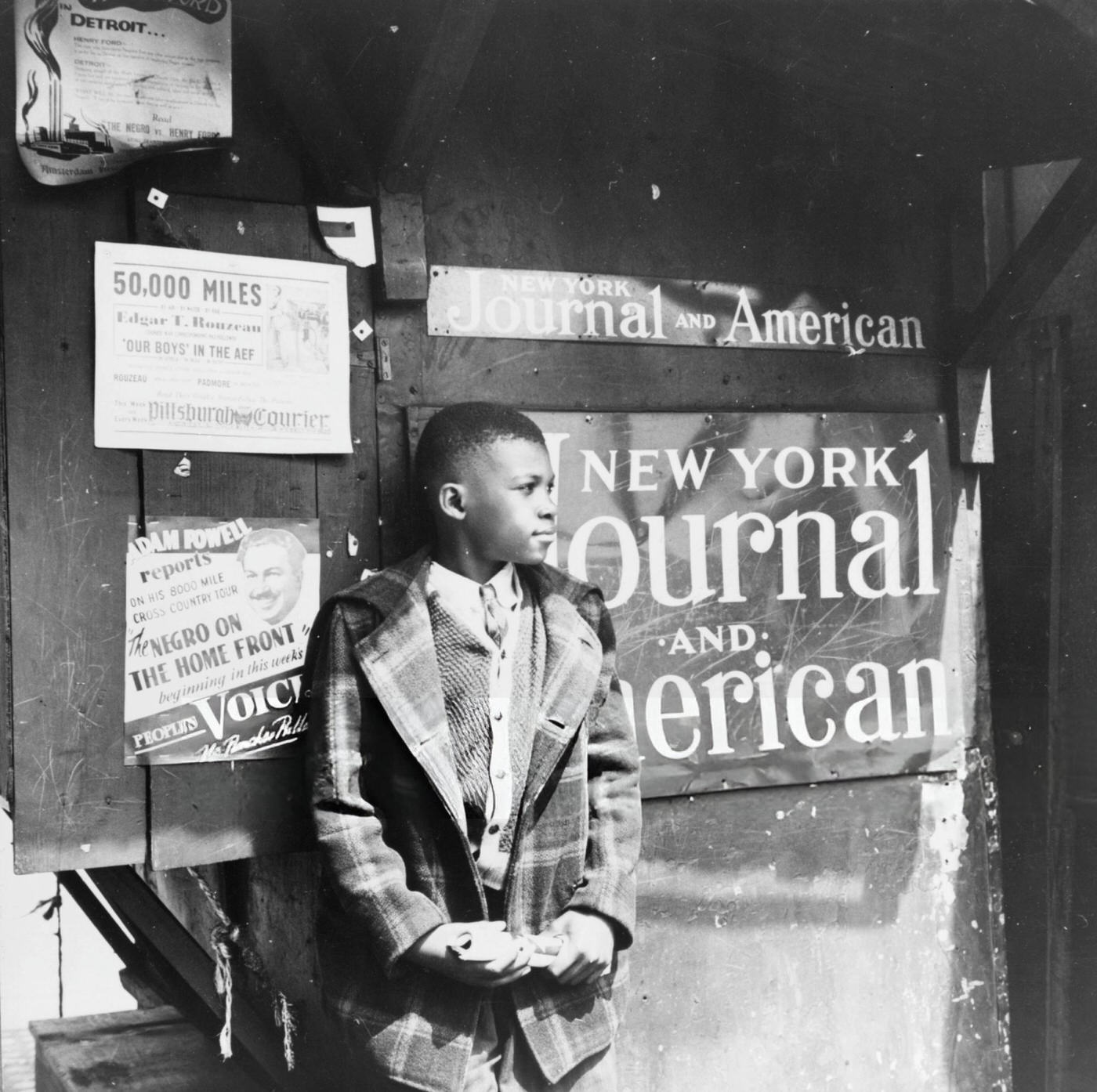

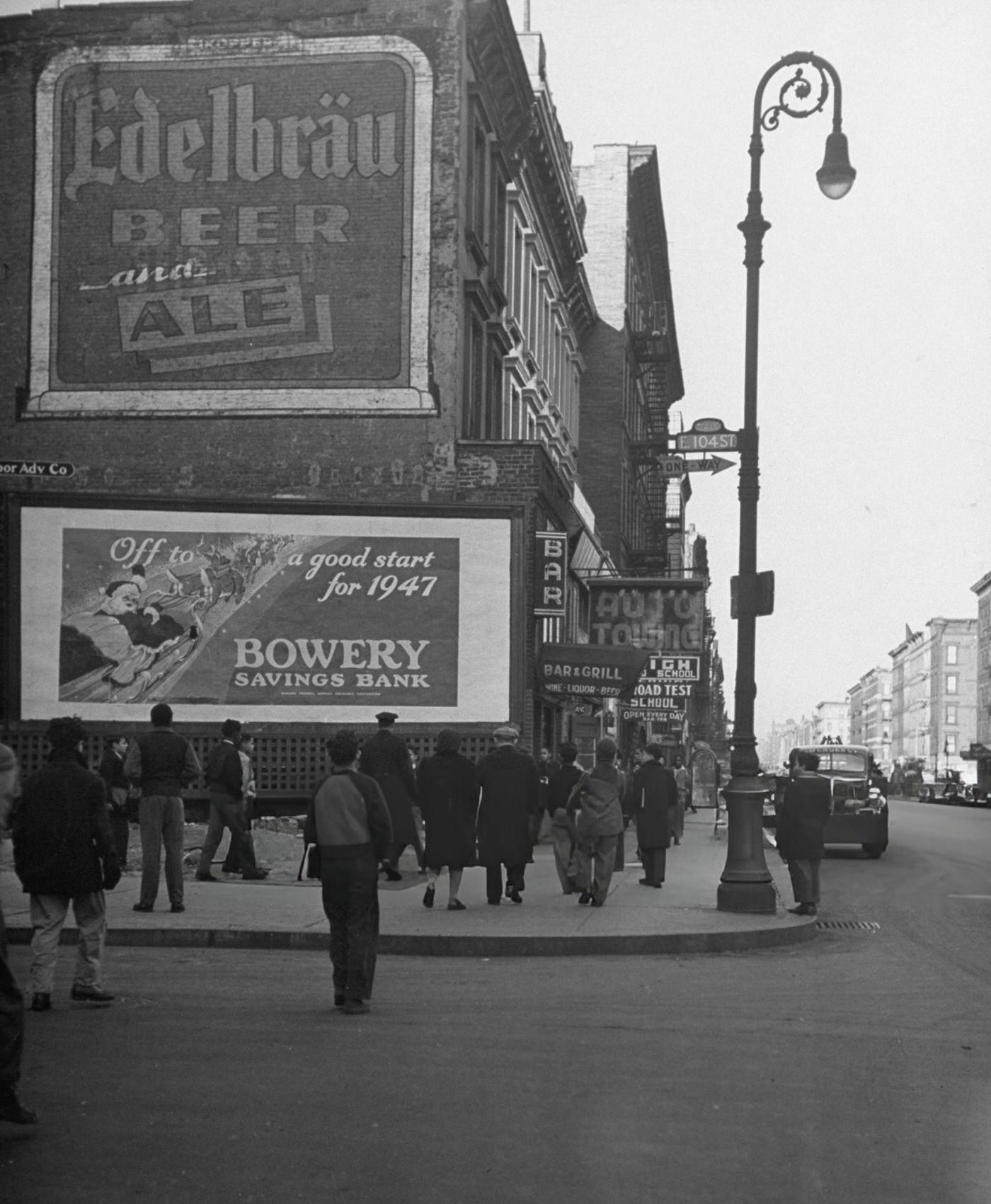

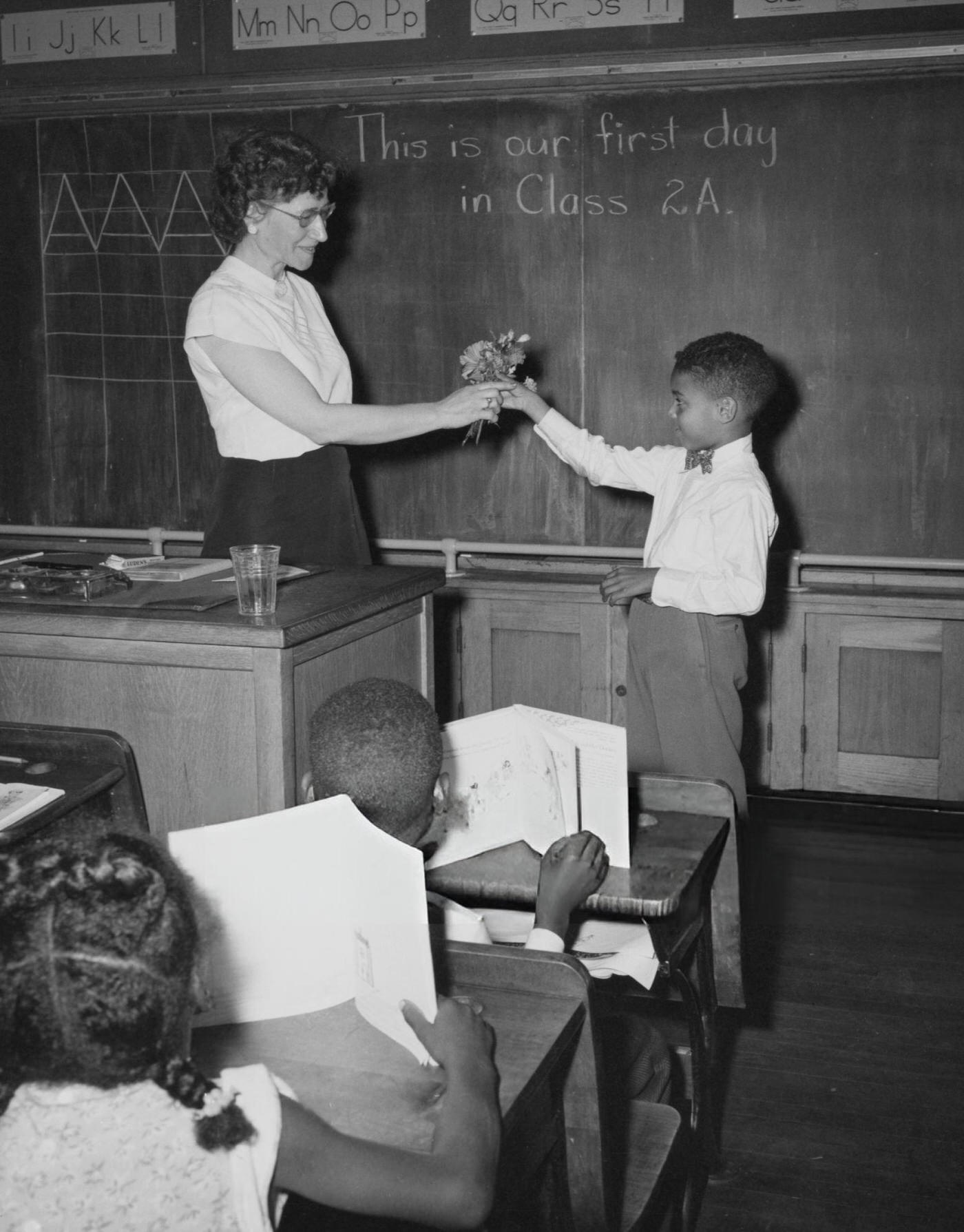

As the 1940s began, the United States started gearing up for World War II. This war mobilization created jobs and began pulling the nation out of the Depression. News of potential work spread, sparking hope throughout Harlem. This hope, combined with the desire to escape racial persecution in the South, fueled the Second Great Migration. Between 1940 and 1970, over five million African Americans left the South. New York State alone saw half a million Black southerners arrive in the first twenty years of this period, many settling in Harlem. By the early 1940s, Harlem housed roughly 300,000 of New York City’s nearly half-million Black residents.

Read more

However, the economic recovery driven by the war did not benefit everyone equally. Persistent discrimination meant many Black New Yorkers were denied the new factory jobs opening up. This created a difficult situation: people arrived seeking opportunity based on the promise of war jobs, only to find many doors still closed due to racism. This gap between hope and reality added to the neighborhood’s existing pressures. The continuous arrival of migrants intensified the strain on Harlem’s resources, particularly housing. Segregation limited where Black families could live, concentrating the growing population into Harlem and worsening problems like overcrowding in aging buildings.

Harlem Answers the Call: World War II

When the United States entered World War II, Harlem residents contributed significantly. New York City provided nearly 900,000 men to the armed forces. Nationally, about one million African Americans served, making up 13 percent of the enlisted military. However, they served under the cloud of segregation. Black soldiers were placed in separate units, often led by white officers, and frequently faced racism within the military structure. Initially, many were assigned to support roles rather than combat.

Despite these conditions, Black soldiers served with distinction. Units like the 369th Infantry, known as the “Harlem Hellfighters” from World War I, had set a precedent for bravery. As the war progressed and manpower needs grew, Black recruits increasingly served in combat roles, including infantry and aviation, with the Tuskegee Airmen becoming famous pilots. Many Black soldiers were also crucial to logistics, driving trucks for the “Red Ball Express,” a vital supply line delivering goods to advancing armies in France.

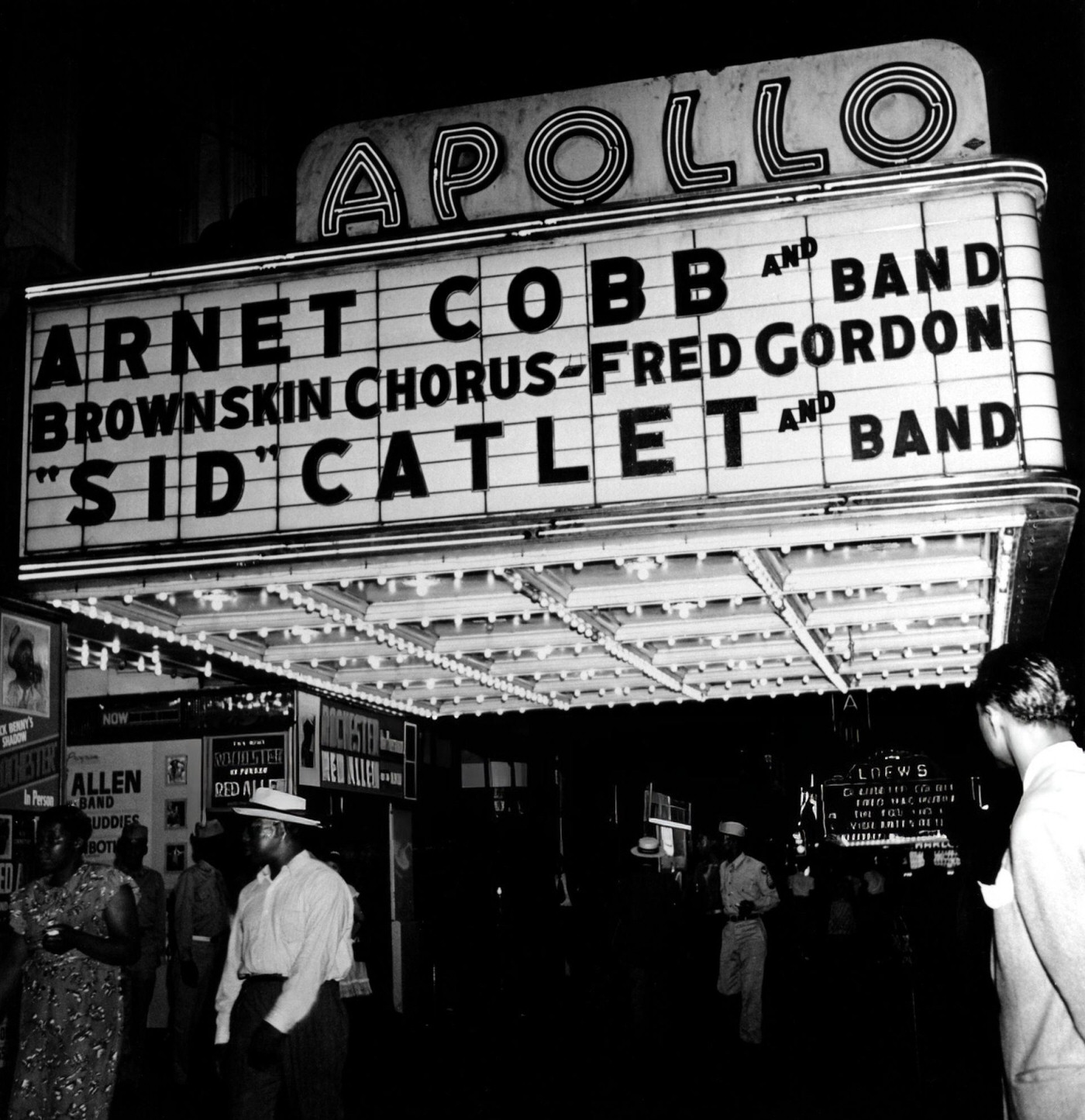

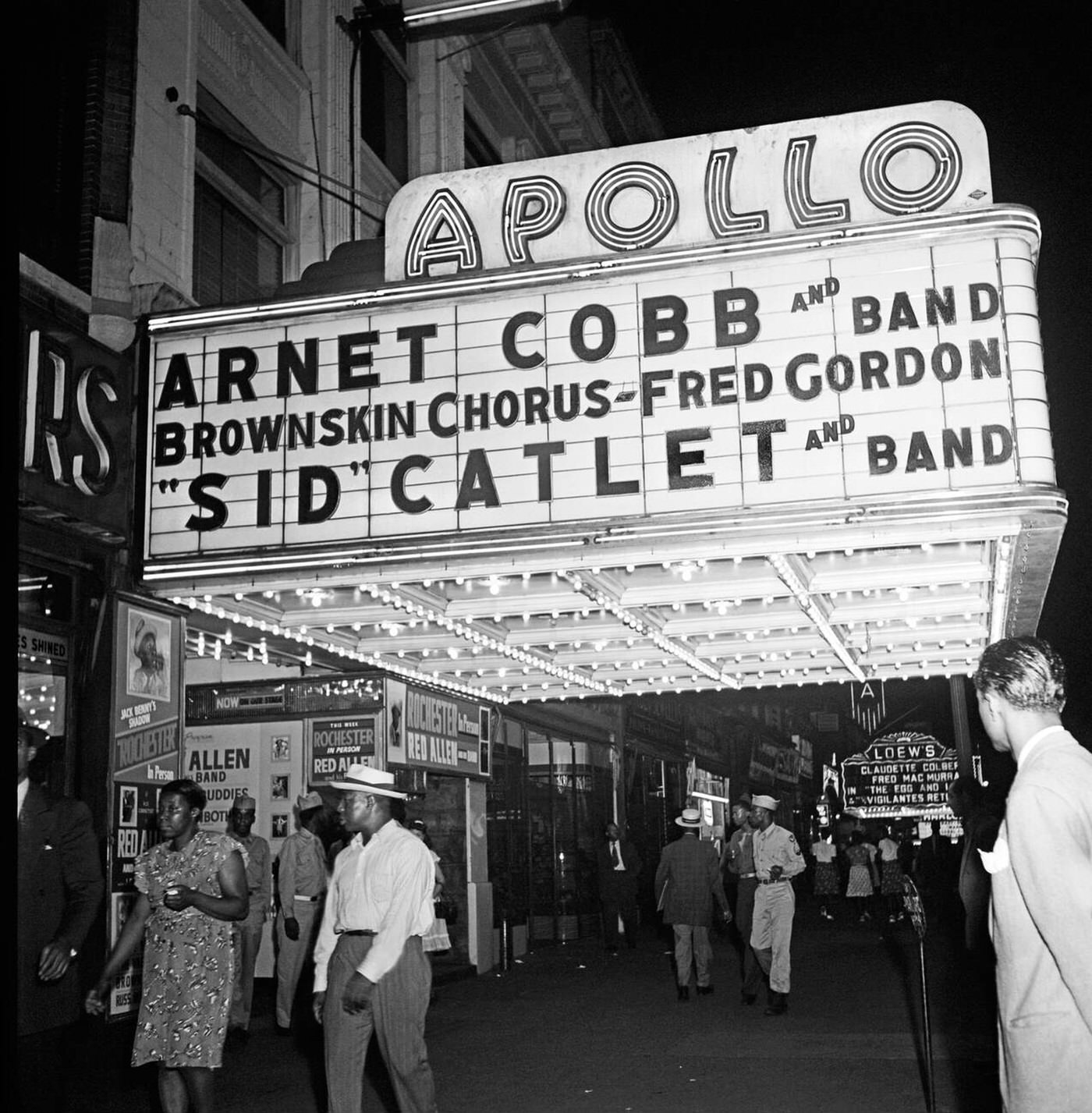

Life on the home front involved shared sacrifices. The government rationed many goods to ensure supplies for the military and prevent inflation. Items like gasoline, tires, sugar, coffee, meat, butter, canned foods, and even shoes required ration coupons, distributed in books to each household member. People participated in scrap drives, collecting rubber, metal, and rags. Many planted “Victory Gardens” to grow their own food. Community support for the troops was visible; the Apollo Theater, for instance, reserved tickets daily for soldiers and hosted “Apollo Night” at the local USO. A national speed limit of 35 miles per hour was even imposed to save fuel and rubber.

The Home Front Struggle: Housing, Work, and Daily Life

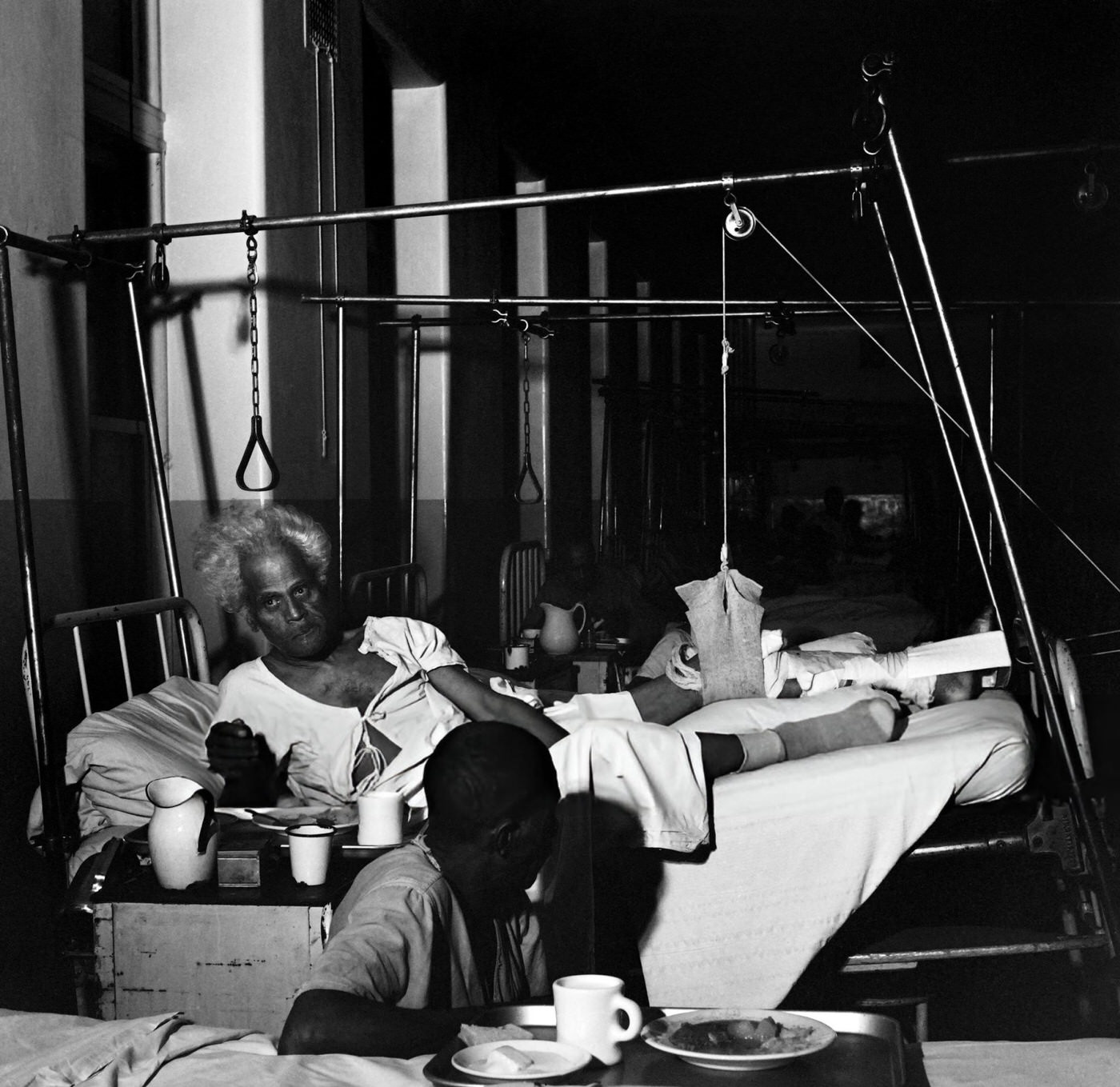

Inside Harlem, daily life was shaped by the ongoing struggle for decent living conditions. Housing was a major crisis. Decades of migration, combined with segregation that prevented Black families from moving to other neighborhoods, led to severe overcrowding. Many residents lived in old tenement buildings that were poorly maintained and deteriorating. Landlords often charged high rents for these substandard apartments.

This situation was worsened by the practice of redlining. Government agencies like the Federal Housing Administration officially labeled Black neighborhoods like Harlem as “high risk” for investment. This designation made it nearly impossible for Black residents to get mortgages to buy homes or loans to repair them. Denied access to loans, families were trapped in the rental market, often paying high prices for poor conditions. Landlords also struggled to get financing for upkeep, contributing to the physical decline of buildings. Redlining systematically blocked Black families from building wealth through homeownership, a key path to economic stability for other groups, and directly contributed to the decay of Harlem’s housing.

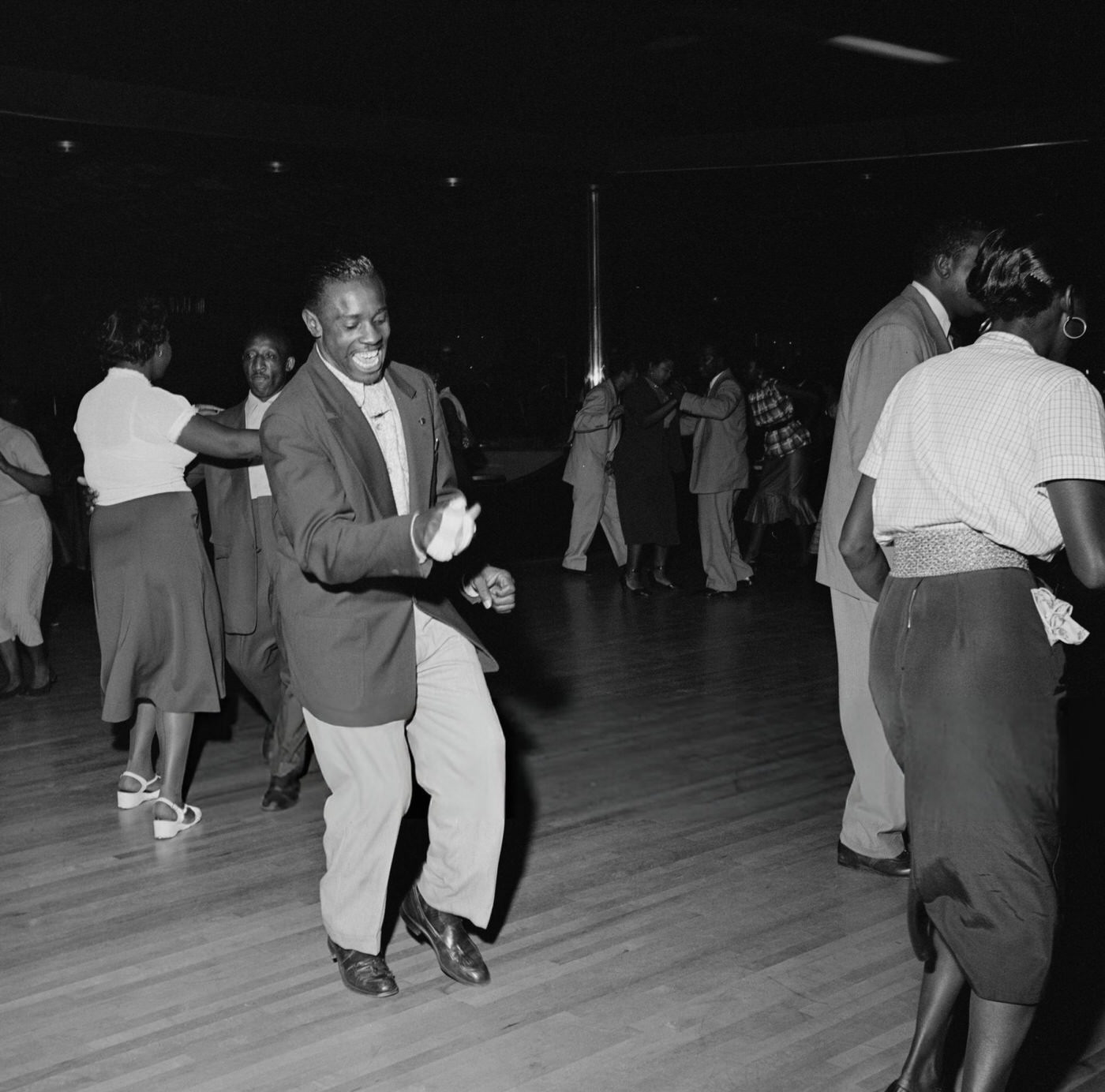

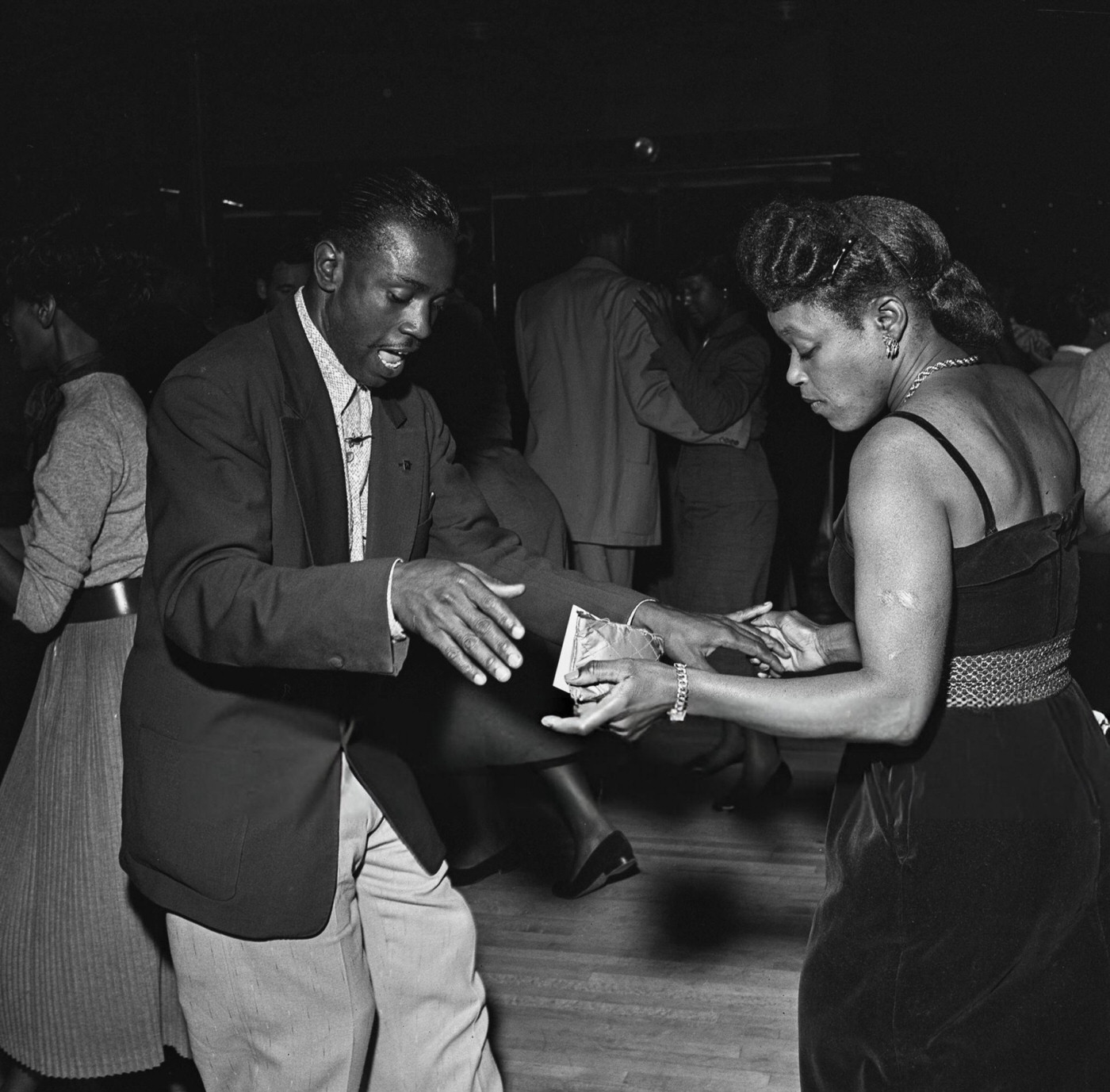

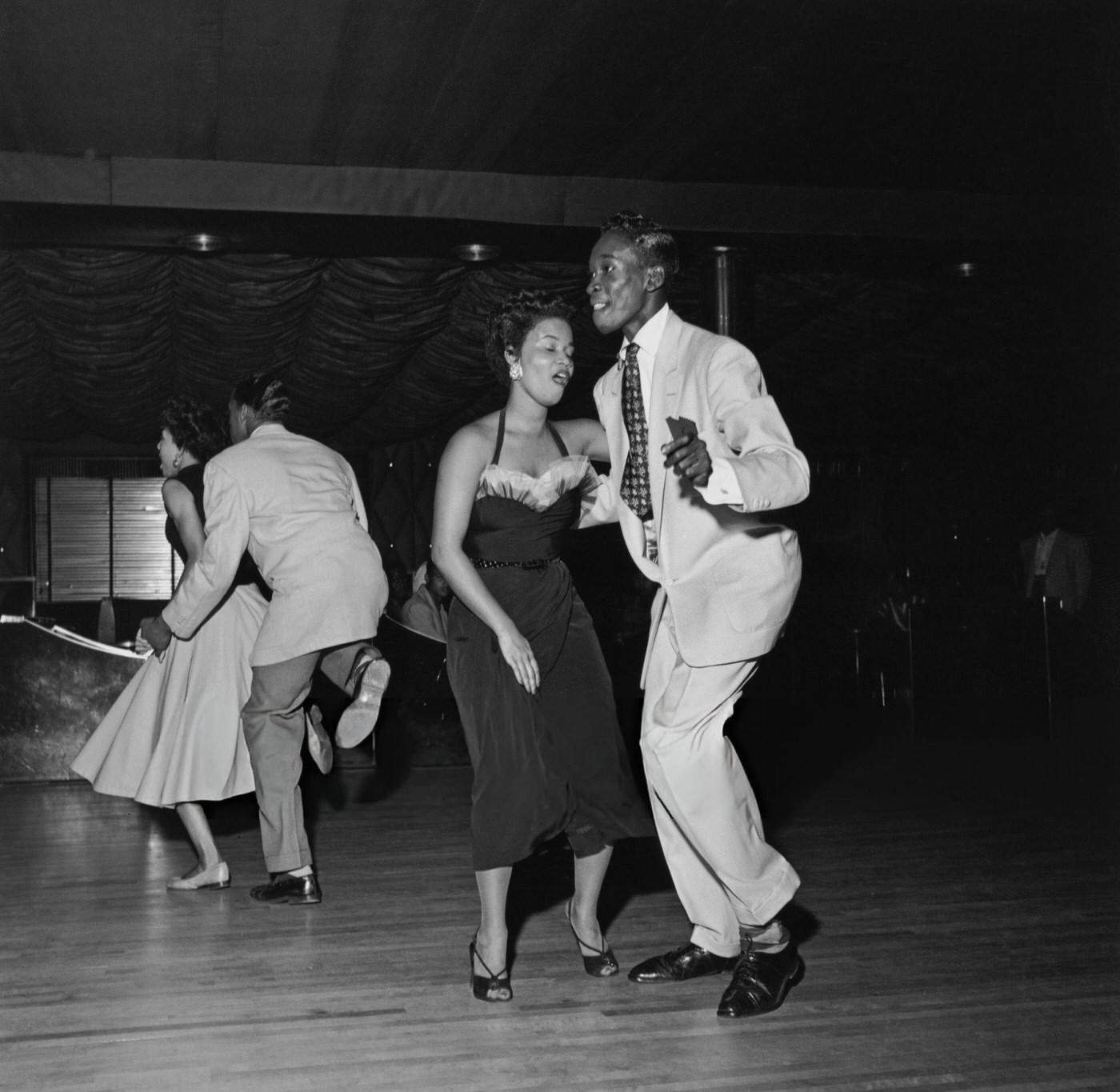

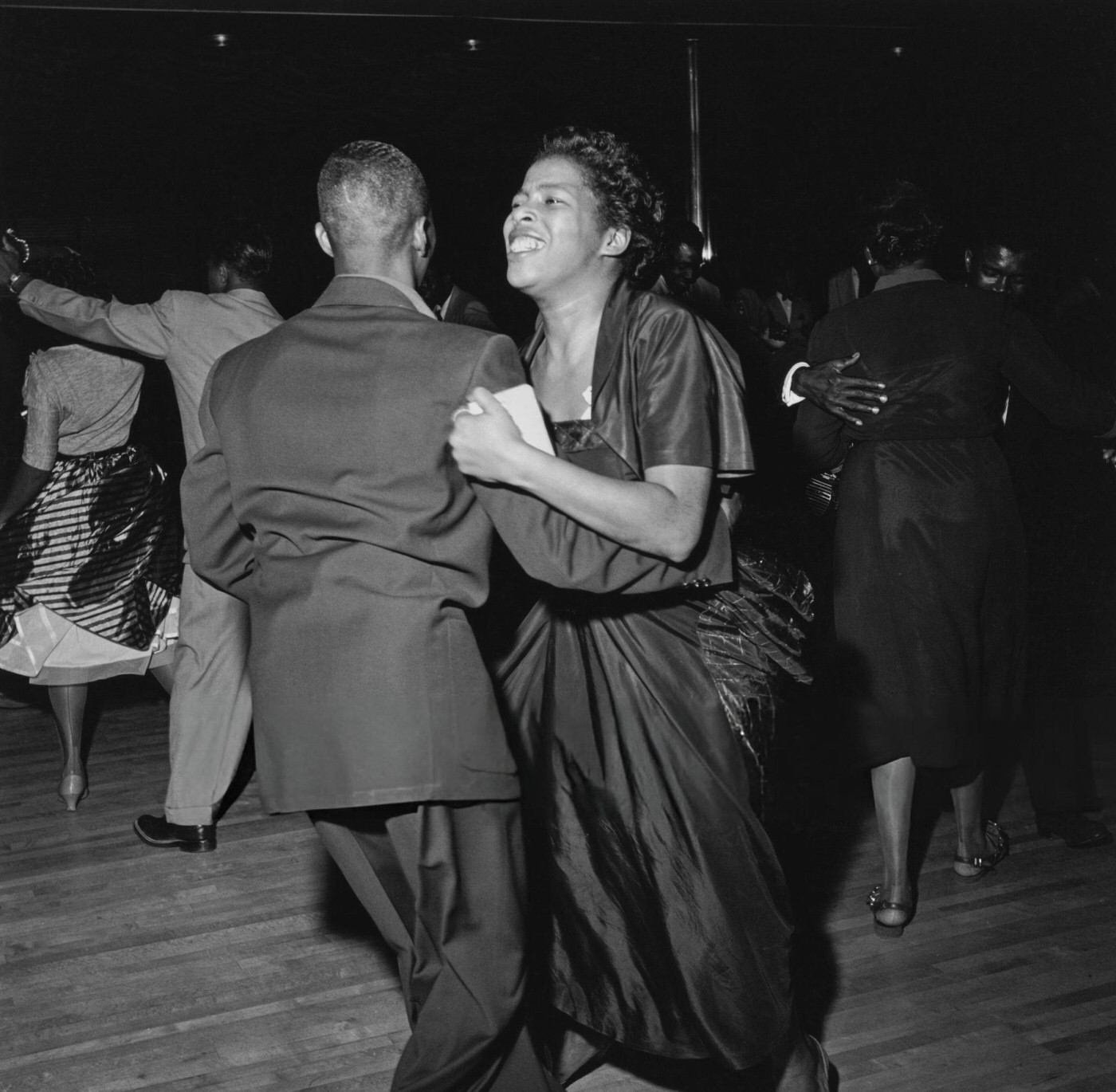

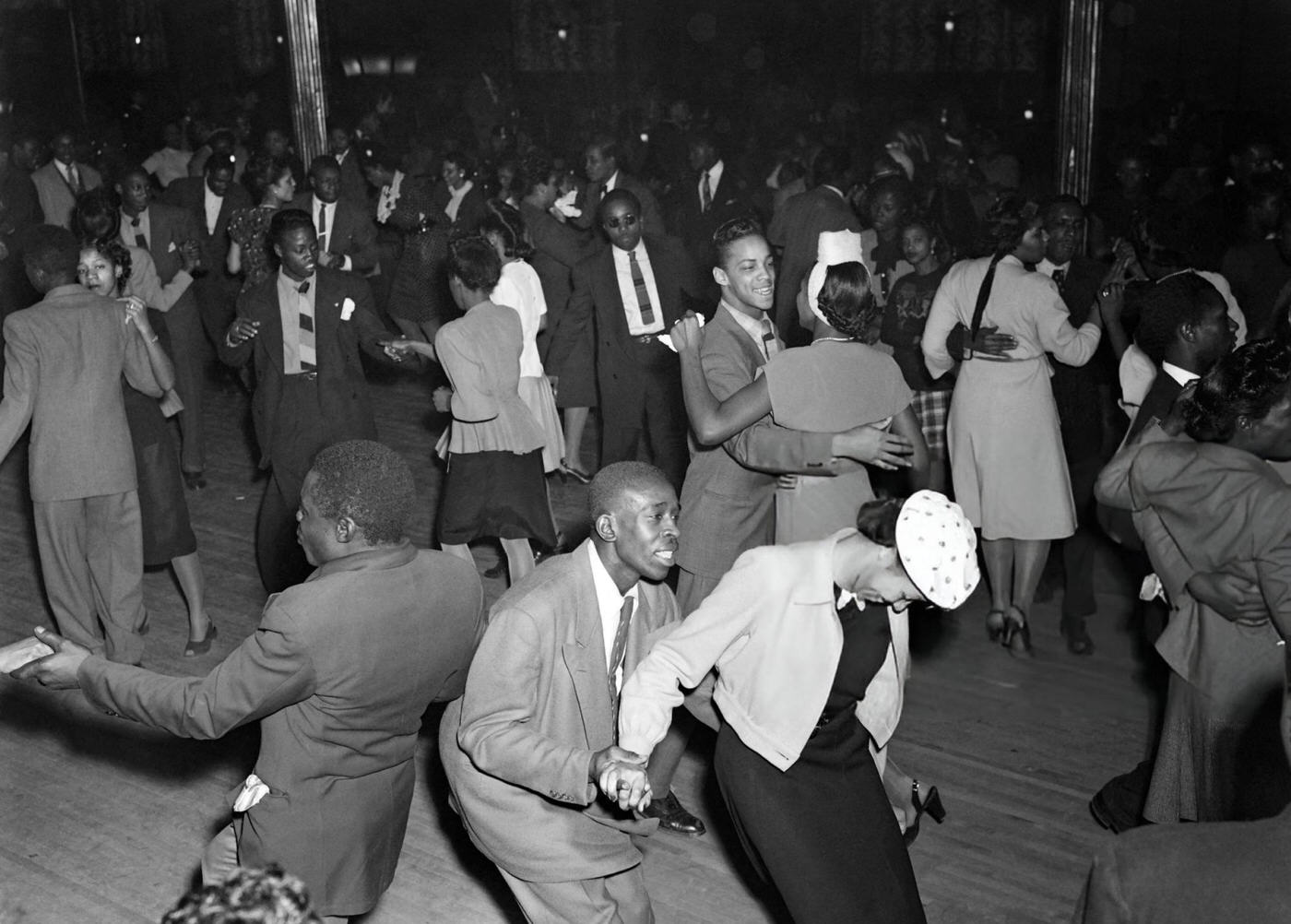

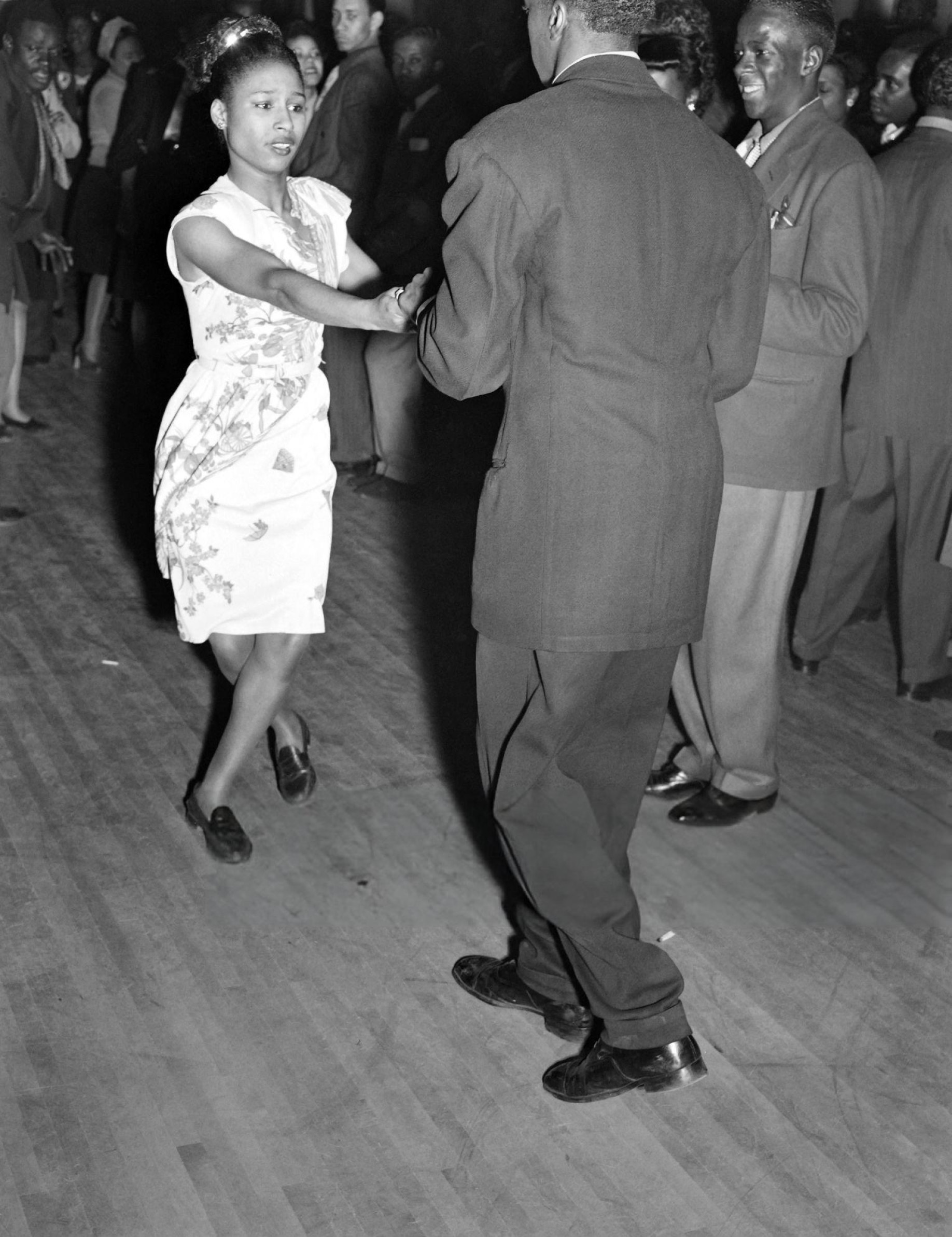

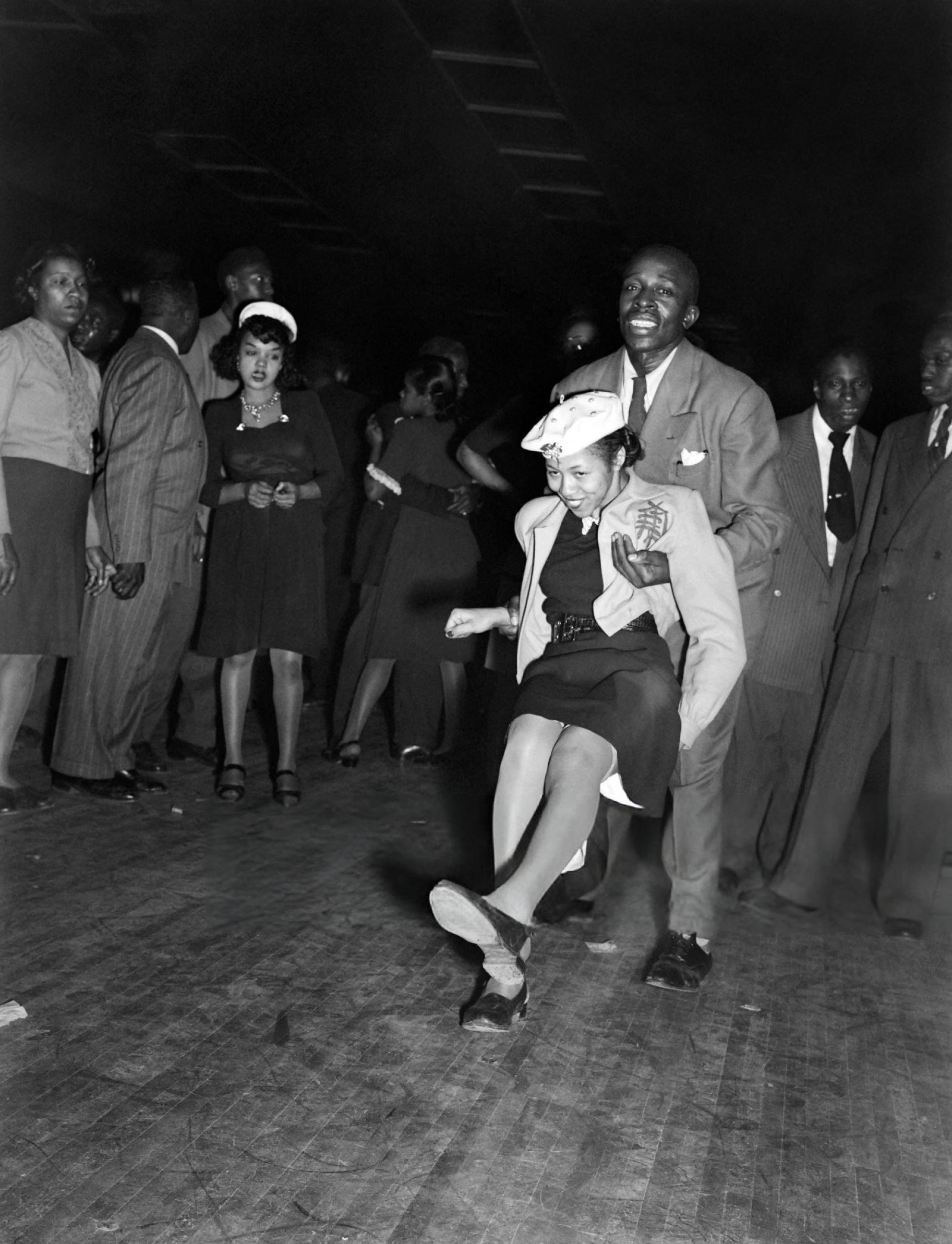

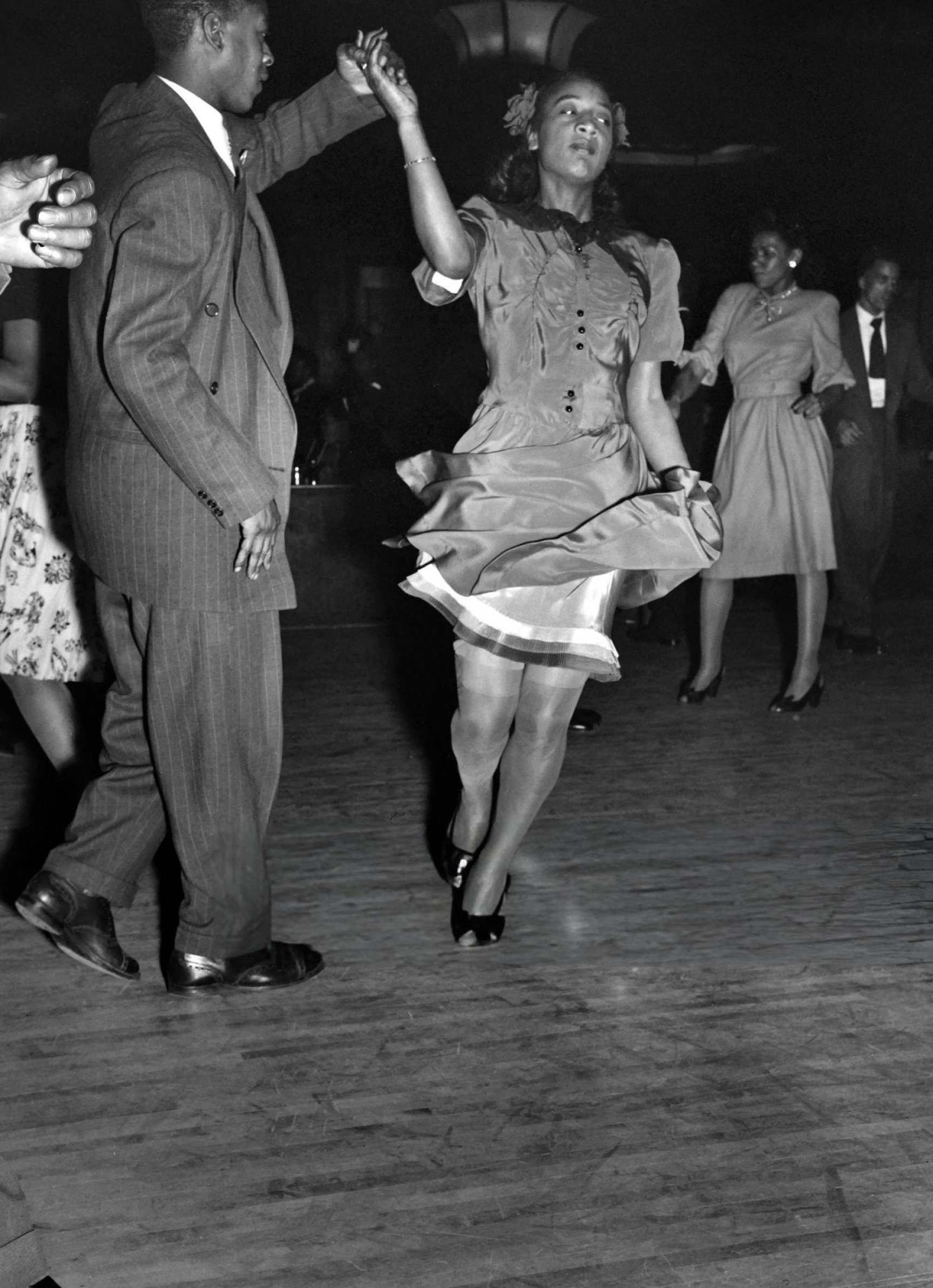

To cope with high rents, Harlemites developed creative solutions like the rent party. These gatherings, popular on Saturday nights, featured music, dancing, food like fried chicken and pork chops, and homemade gin. Guests paid a small admission fee, perhaps 25 cents, and the money collected helped the host pay their rent. Rent parties were more than just fundraisers; they were important social events that built community solidarity.

Some government efforts addressed housing. The Harlem River Houses, built in the late 1930s as part of the New Deal, were among the first federally funded public housing projects in New York City. Designed specifically for African Americans, they offered better living conditions than the surrounding tenements. However, such projects were too few to solve the widespread housing shortage, and construction slowed significantly during the war years as resources were diverted.

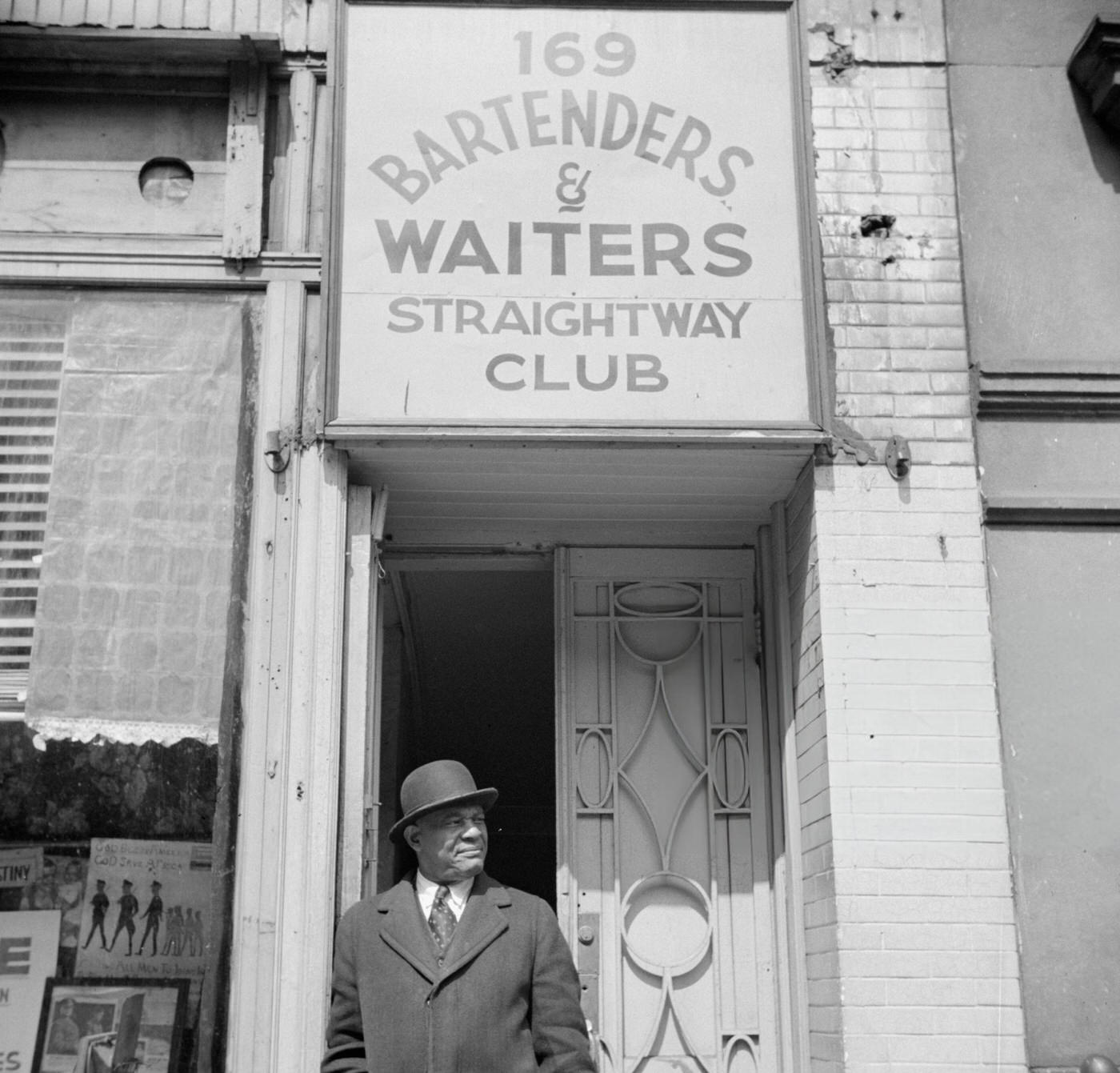

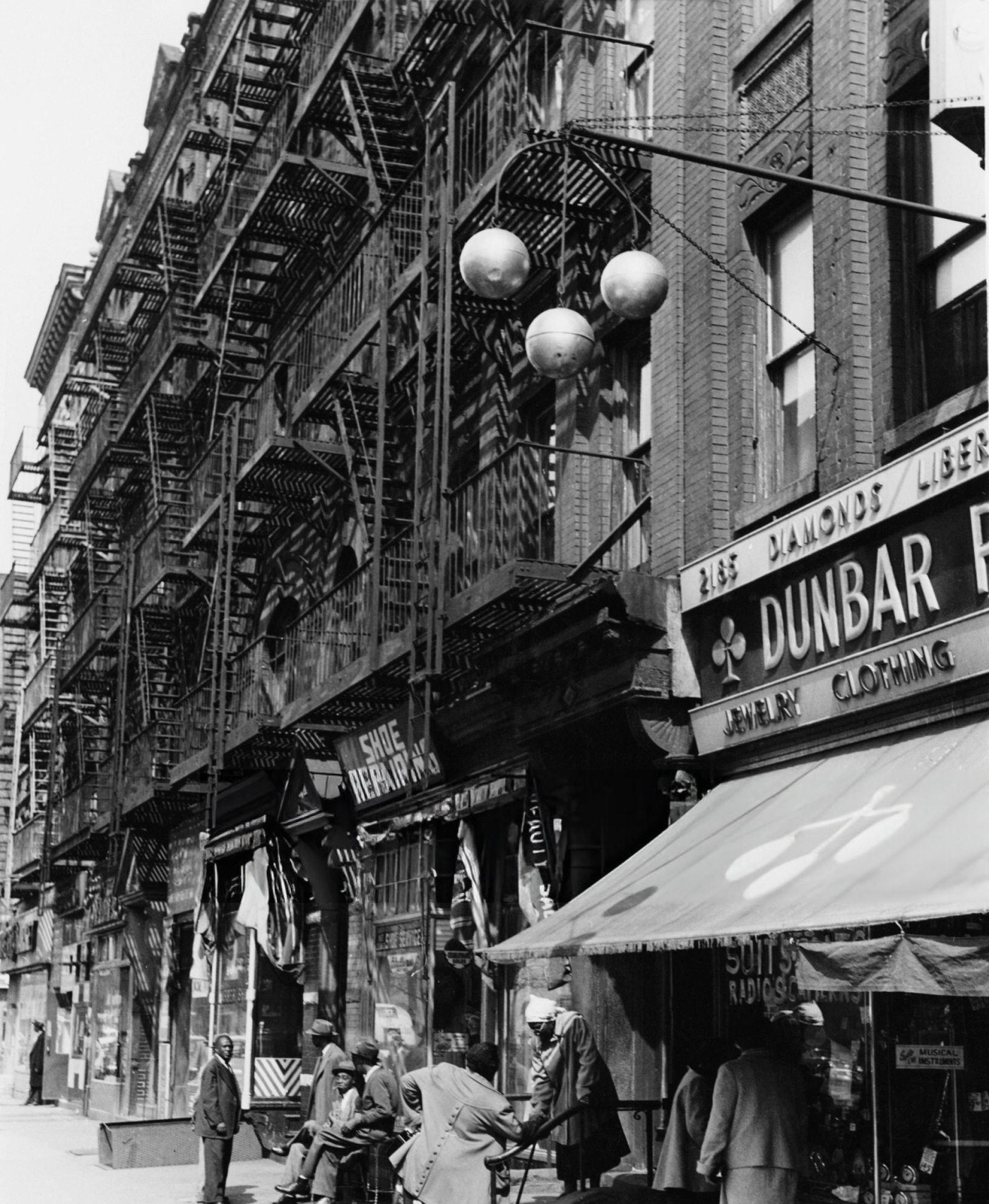

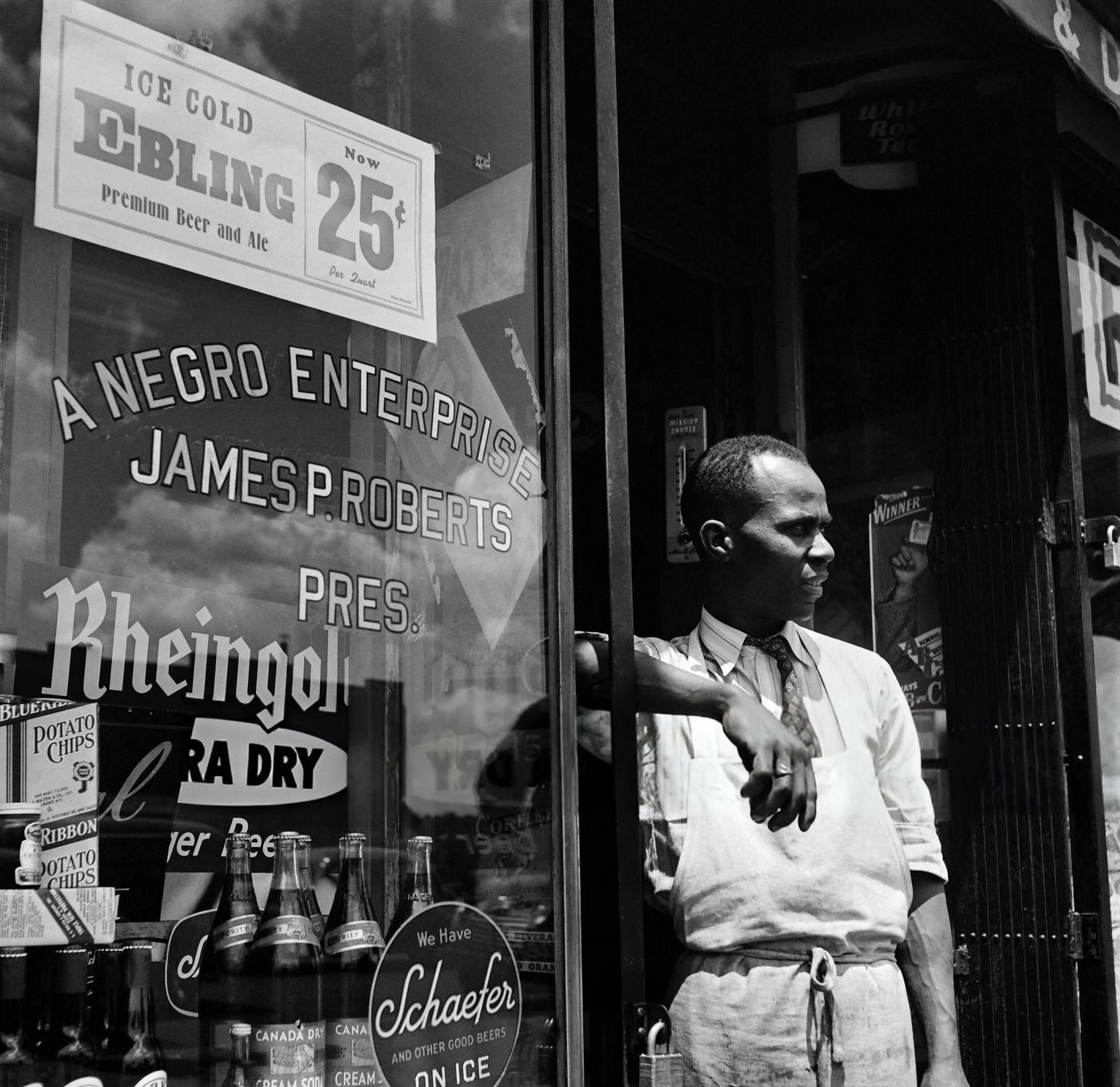

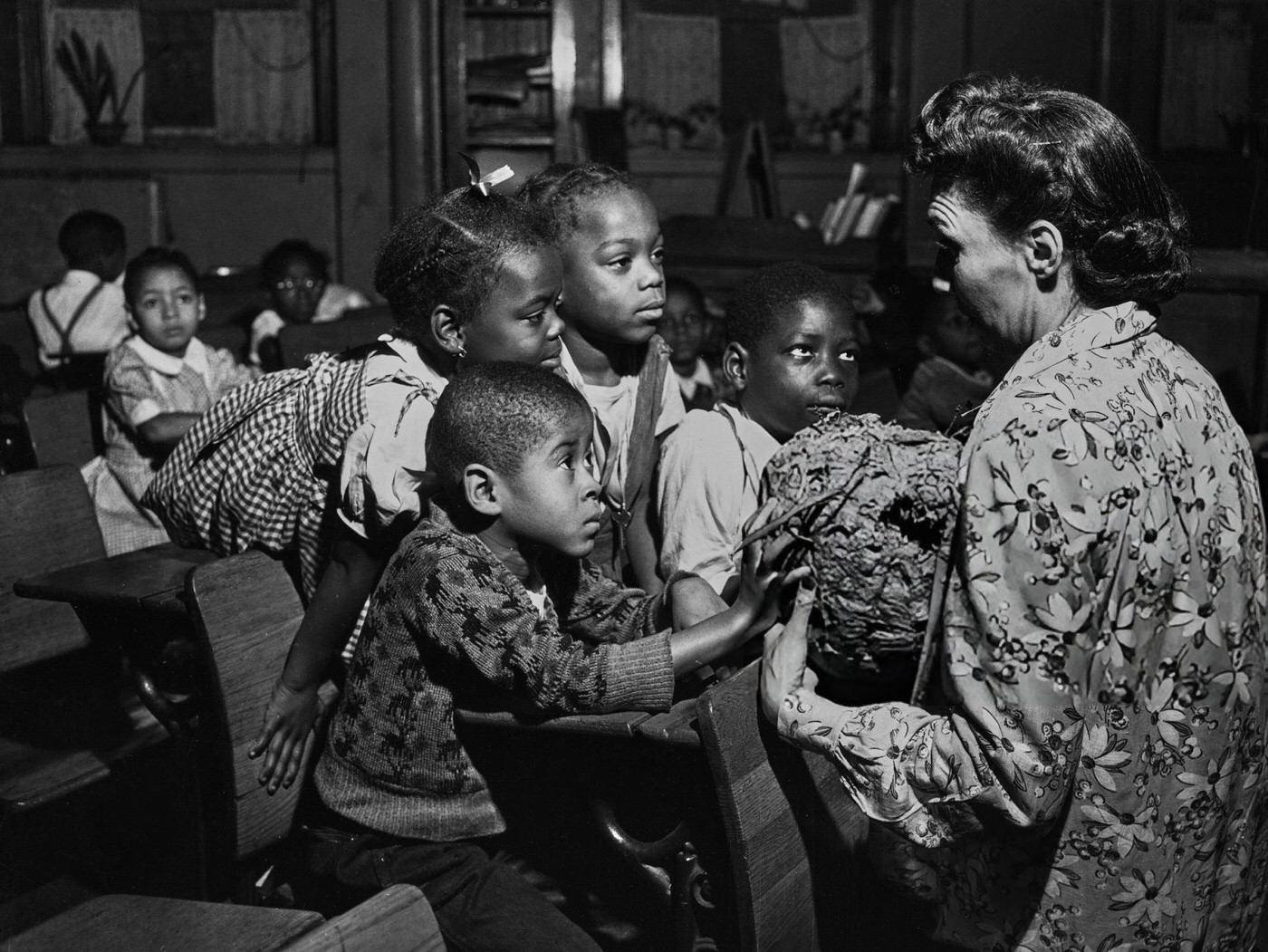

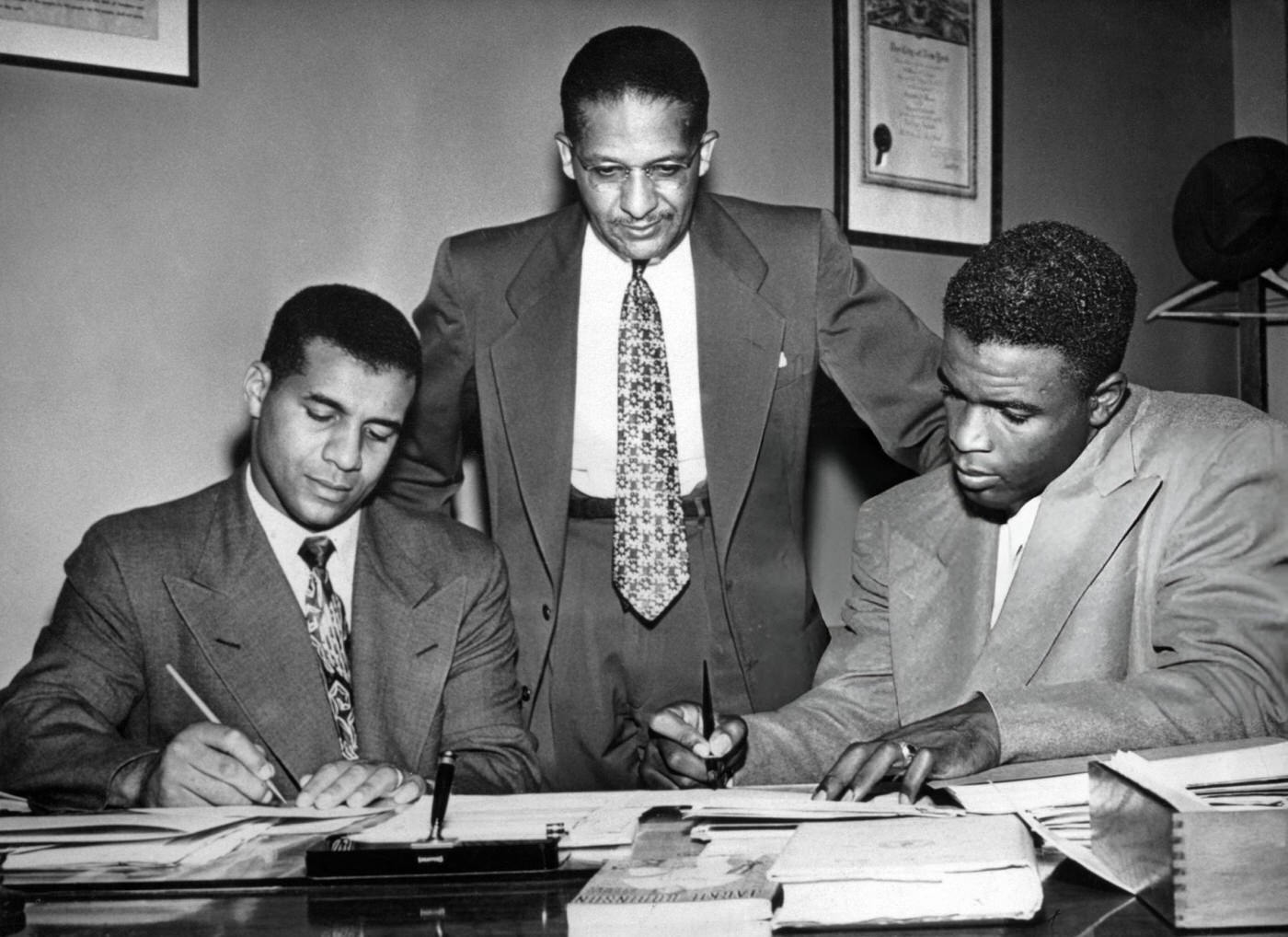

Finding work remained a challenge. While some found jobs in war industries, many faced discrimination. Common jobs for Black Harlemites included service positions, domestic work (especially for women before the war), and lower-level industrial jobs. A significant source of frustration was that many businesses located right in Harlem, often owned by white proprietors, refused to hire Black residents, particularly for skilled or white-collar positions.

The Birth of Bebop: A New Sound Emerges

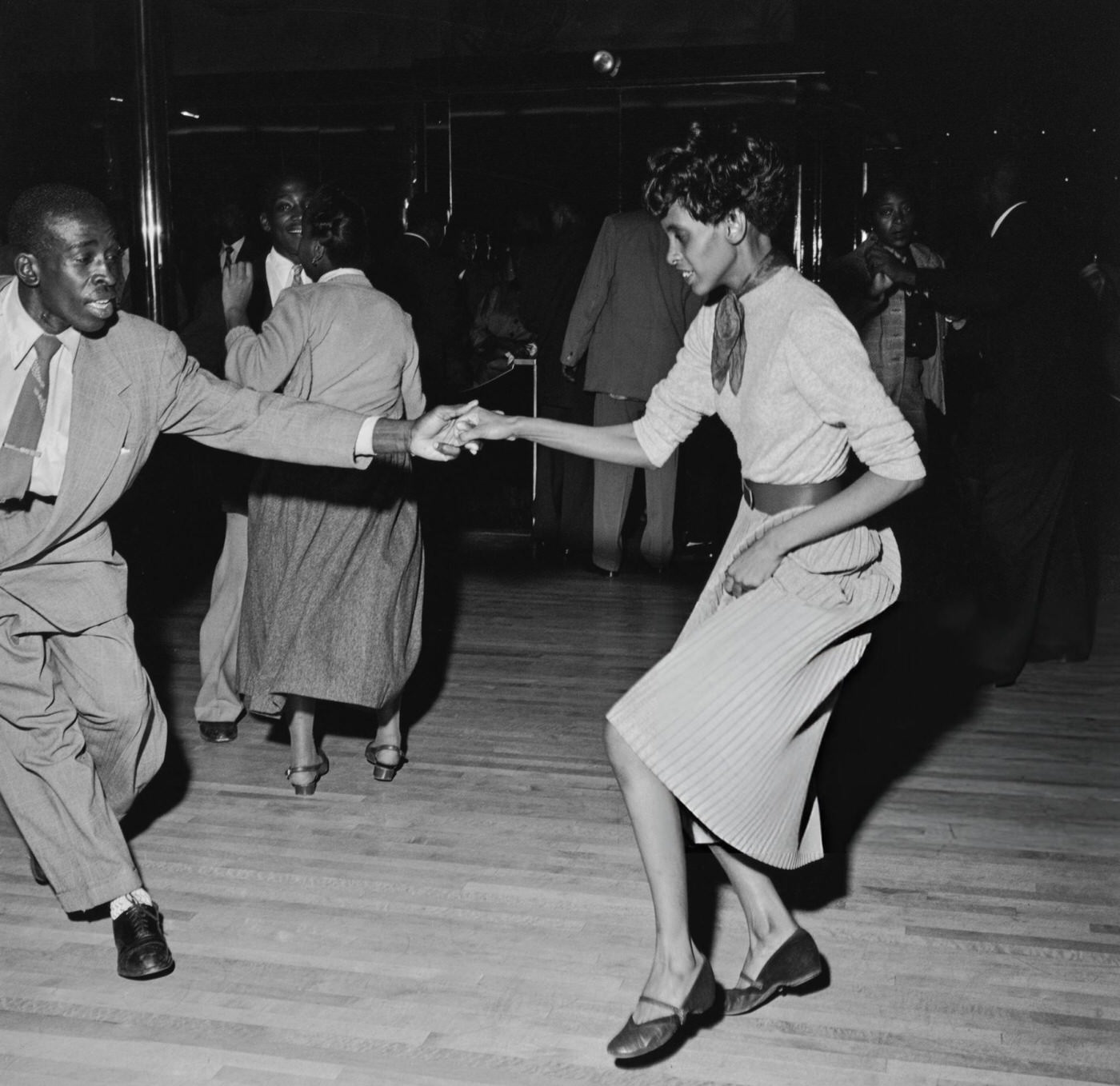

Harlem in the 1940s was the cradle of a revolutionary new form of jazz: bebop. Nightclubs like Minton’s Playhouse, located in the Hotel Cecil on West 118th Street, became legendary laboratories for this new sound. Clark Monroe’s Uptown House on West 134th Street was another critical venue where the music took shape. While the Savoy Ballroom remained famous for swing dancing , Minton’s and Monroe’s fostered a different kind of musical exploration.

Minton’s Playhouse, founded by Henry Minton and managed in the early 40s by former bandleader Teddy Hill, became the epicenter. Hill hired talented musicians for the house band, including pianist Thelonious Monk and drummer Kenny Clarke. The club hosted famous Monday night jam sessions, attracting musicians after their regular gigs ended. Because Minton had ties to the musicians’ union, players could experiment freely without fear of being fined for jamming, which was technically against union rules. These sessions, filled with creative energy, were where bebop was born.

Bebop was a deliberate departure from the popular, dance-oriented swing music of the era. It was complex, fast-paced, and technically demanding, intended for attentive listening rather than dancing. Bebop musicians saw themselves as artists, not just entertainers. The music featured intricate melodies (called “heads”) played in unison, followed by extended, virtuosic solos based on complex harmonies and chromatic scales. It was typically played by small groups, often a quintet with trumpet, saxophone, piano, bass, and drums. This shift toward complexity and improvisation represented a conscious move by young Black musicians to assert their artistic freedom and push the boundaries of jazz, creating a distinct “art music” in spaces they controlled, away from commercial pressures.

The pioneers of bebop honed their sound in these Harlem clubs. Key figures included alto saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, pianists Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell, drummers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach, and guitarist Charlie Christian. Parker and Gillespie, in particular, were central innovators, even forming their own working bebop group in 1944. Their experiments at Minton’s and Monroe’s fundamentally changed the course of American music.

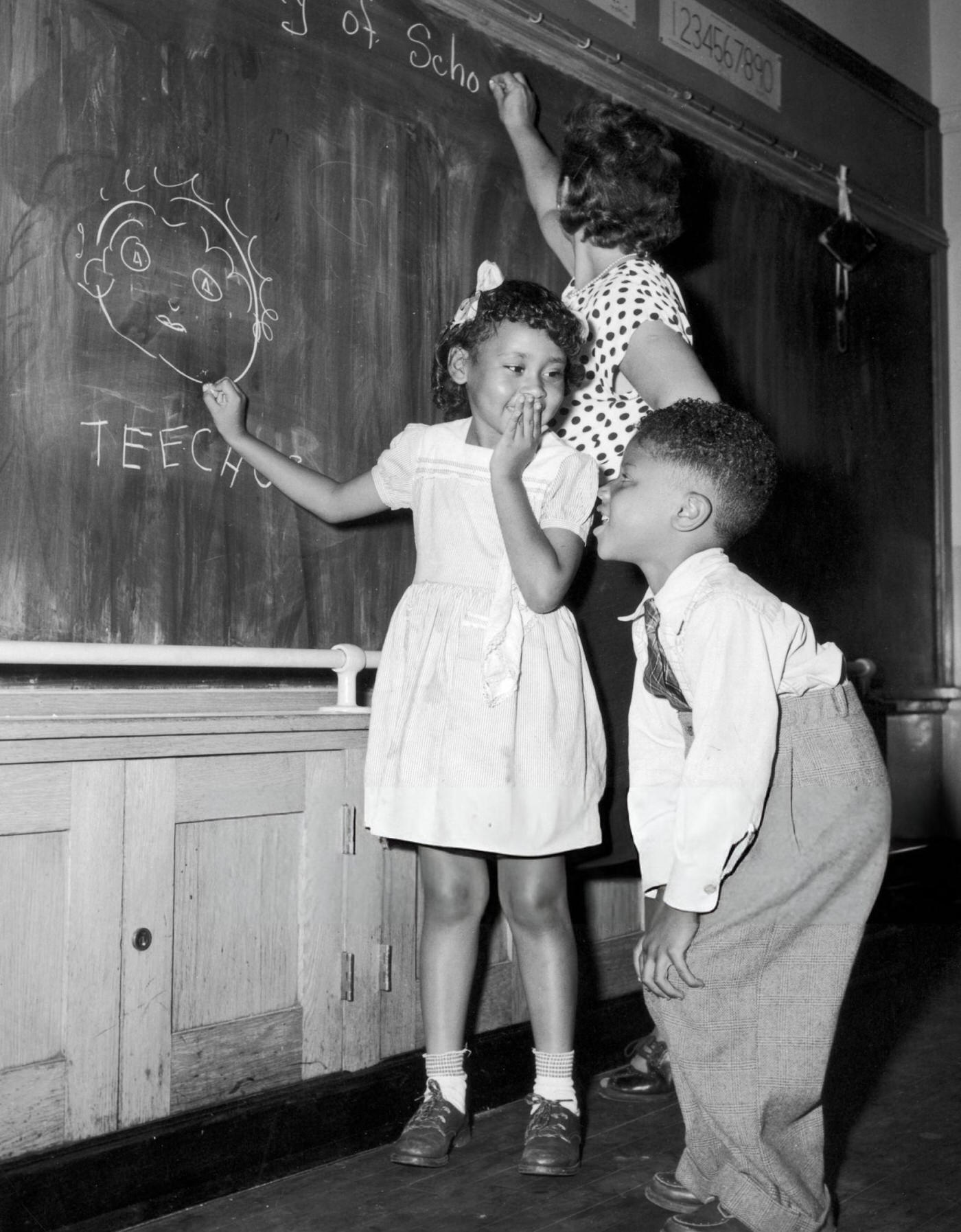

Creativity and Performance: Arts, Literature, and the Apollo

Harlem’s creative spirit extended beyond music. Though the peak of the Harlem Renaissance had passed, the 1940s saw continued literary and artistic production. Writers grappled with the realities of urban life, racism, and the search for equality. Ann Petry published her influential novel The Street in 1946, offering a stark portrayal of a Black woman’s struggles against the destructive forces of her environment. Ralph Ellison was developing his masterpiece Invisible Man (published 1952), which explored the psychological toll of racism. A young James Baldwin was also beginning his literary journey. The powerful social realism of Richard Wright, whose Native Son appeared in 1940, continued to influence many writers.

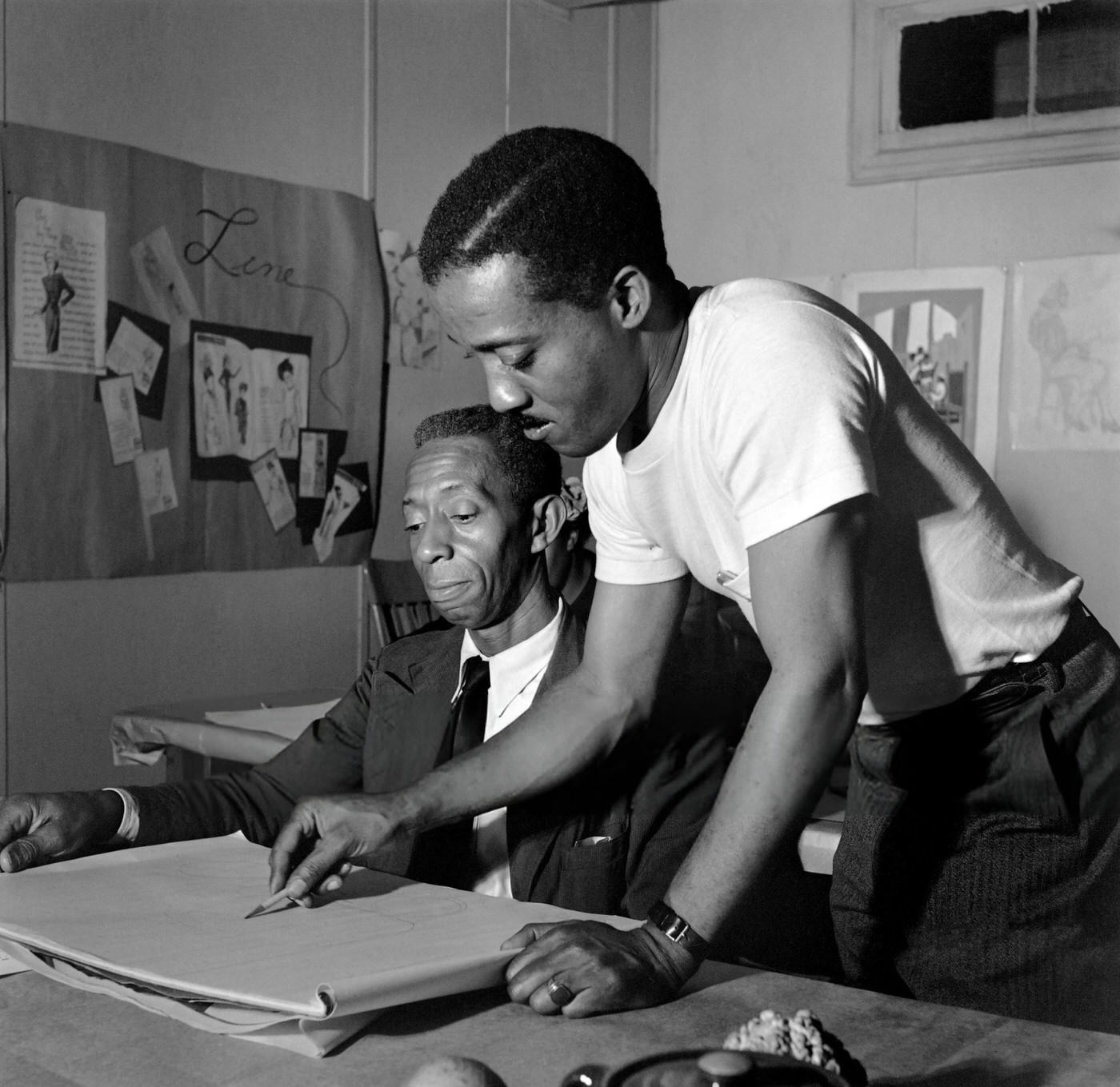

In the visual arts, painters and sculptors documented Black history and contemporary life. Jacob Lawrence rose to prominence during this decade. Mentored by artists like Charles Alston and Augusta Savage, Lawrence developed a distinctive style, creating narrative series like his famous Migration Series (completed 1941) and vivid scenes of Harlem. Romare Bearden, another key figure, was also active, painting scenes inspired by the South and religion before later exploring abstraction and collage. Augusta Savage, an important sculptor and teacher from the Renaissance era, continued to be a vital force, nurturing younger talent. Community art spaces, such as Alston’s “306” studio and the Harlem Community Art Center (run by Savage), provided crucial meeting places and workspaces for artists.

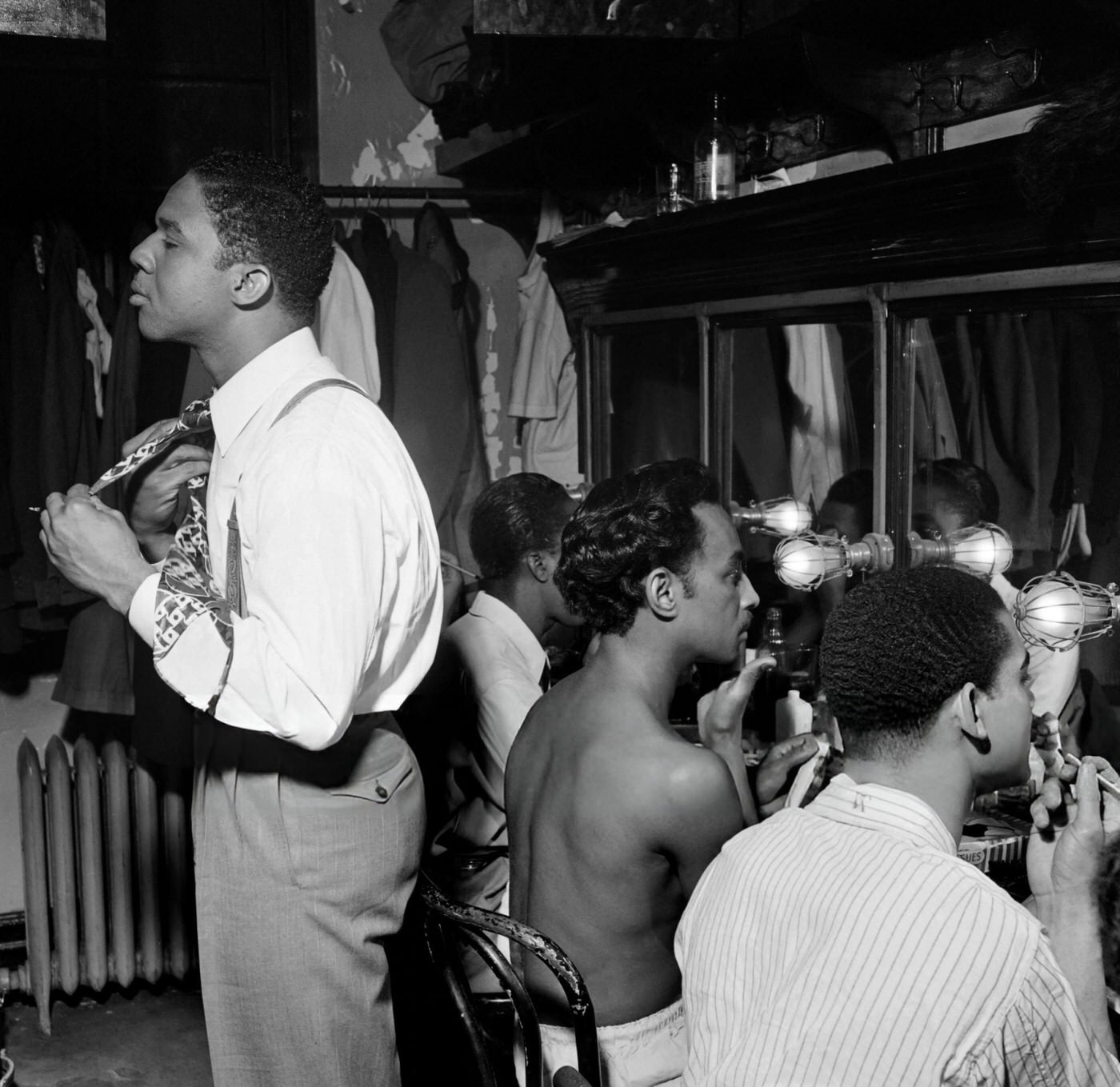

At the heart of Harlem’s entertainment world stood the Apollo Theater on 125th Street. It was more than just a venue; it was a cultural institution and a vital platform for Black performers. During the 1940s, the Apollo stage hosted established stars like Lionel Hampton and saw the debuts of future legends like Dinah Washington and Sammy Davis Jr.. It held the distinction of being the largest employer of Black theatrical workers in the nation. The theater also reflected the times, setting aside tickets for soldiers during World War II and seeing its comedians abandon the racist practice of blackface makeup.

The Apollo’s renowned Amateur Night continued its tradition of discovering new talent. Aspiring performers faced a famously tough audience, but success could launch a career. During the 1940s, singers Sarah Vaughan and Ruth Brown were among the hopefuls who won the competition. They followed in the footsteps of late 1930s winners like Ella Fitzgerald and Pearl Bailey, whose careers were taking off. By providing a space where Black artists could gain exposure and opportunity often denied elsewhere, the Apollo, especially through Amateur Night, acted as a crucial incubator, shaping the future of American popular music.

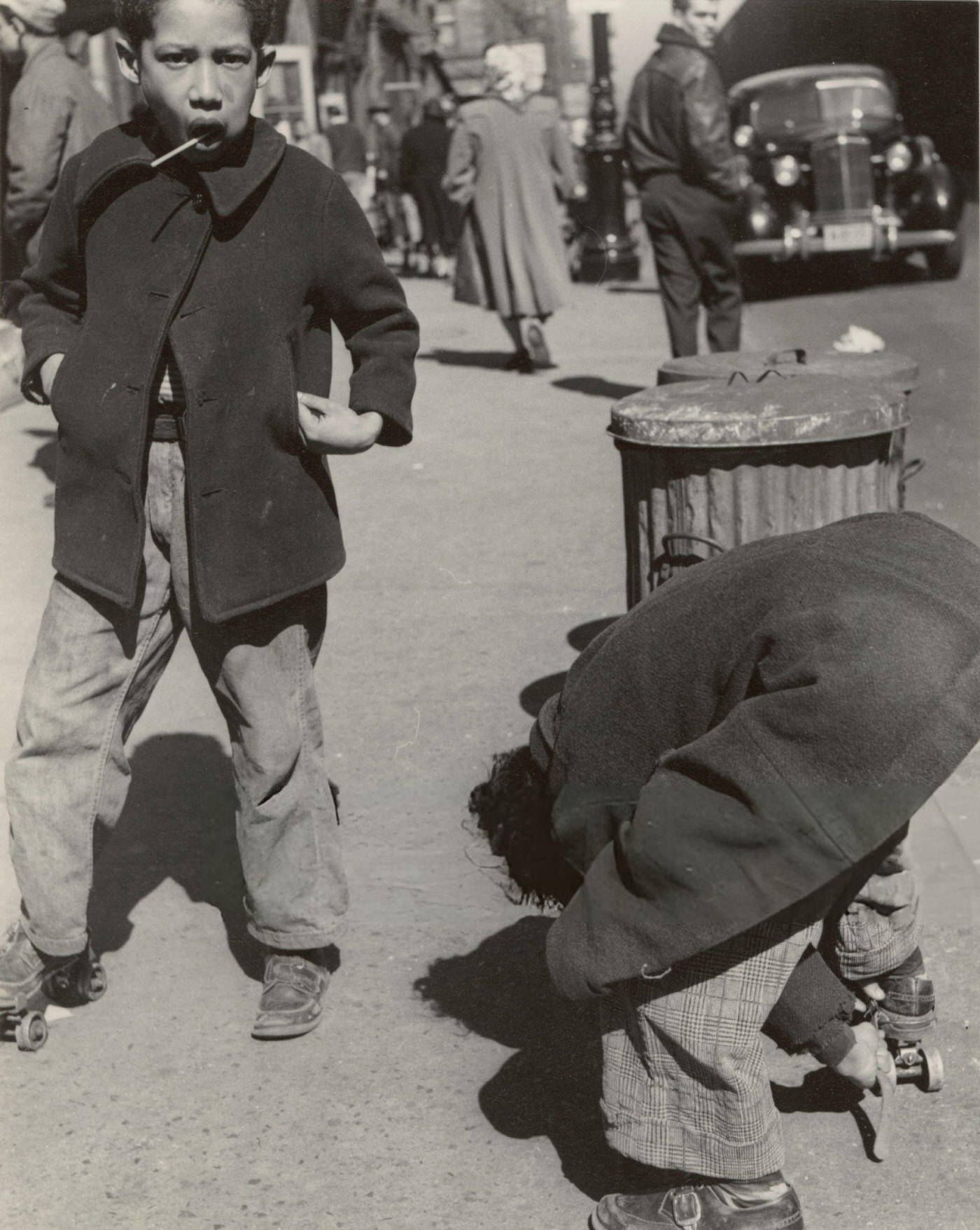

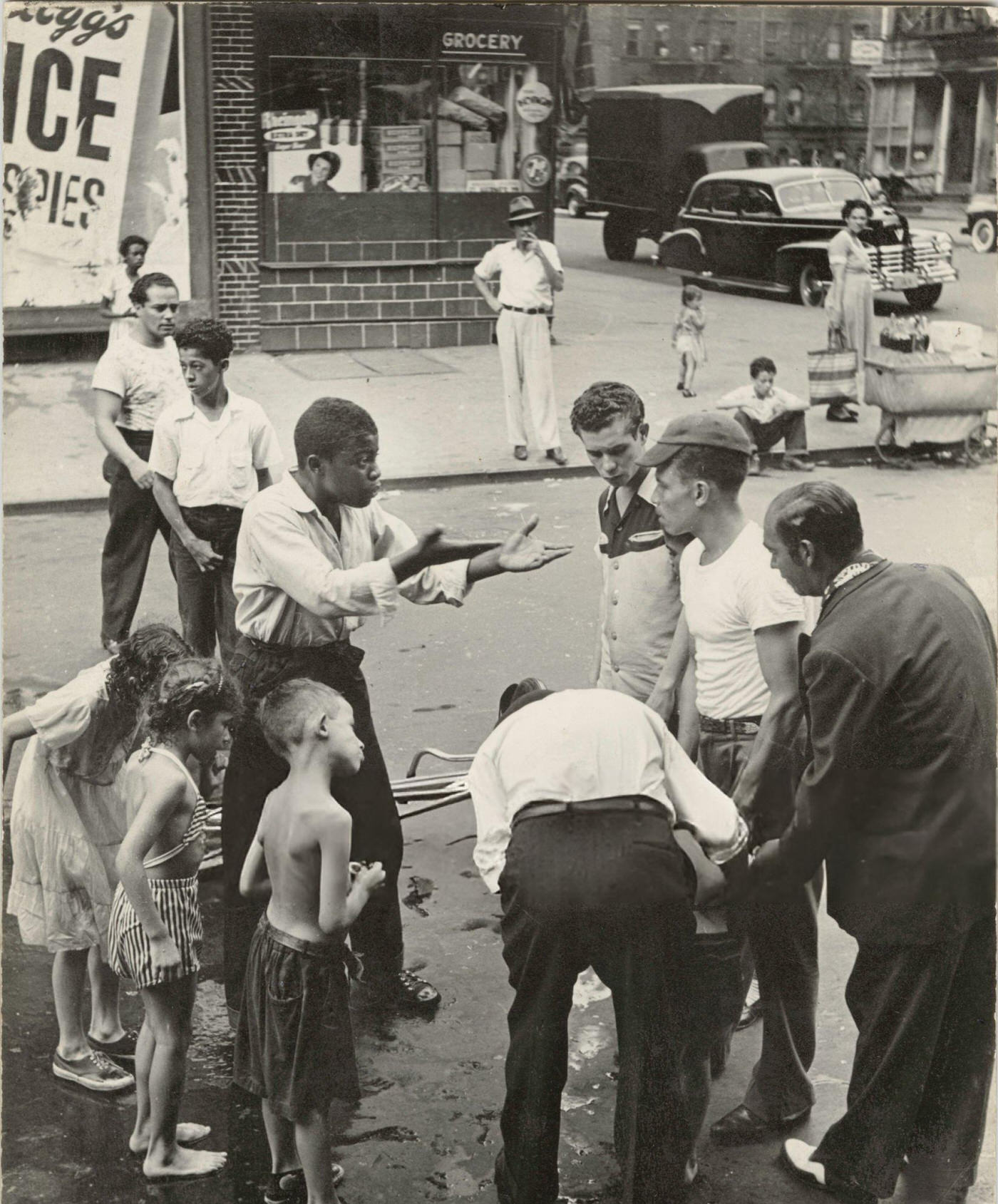

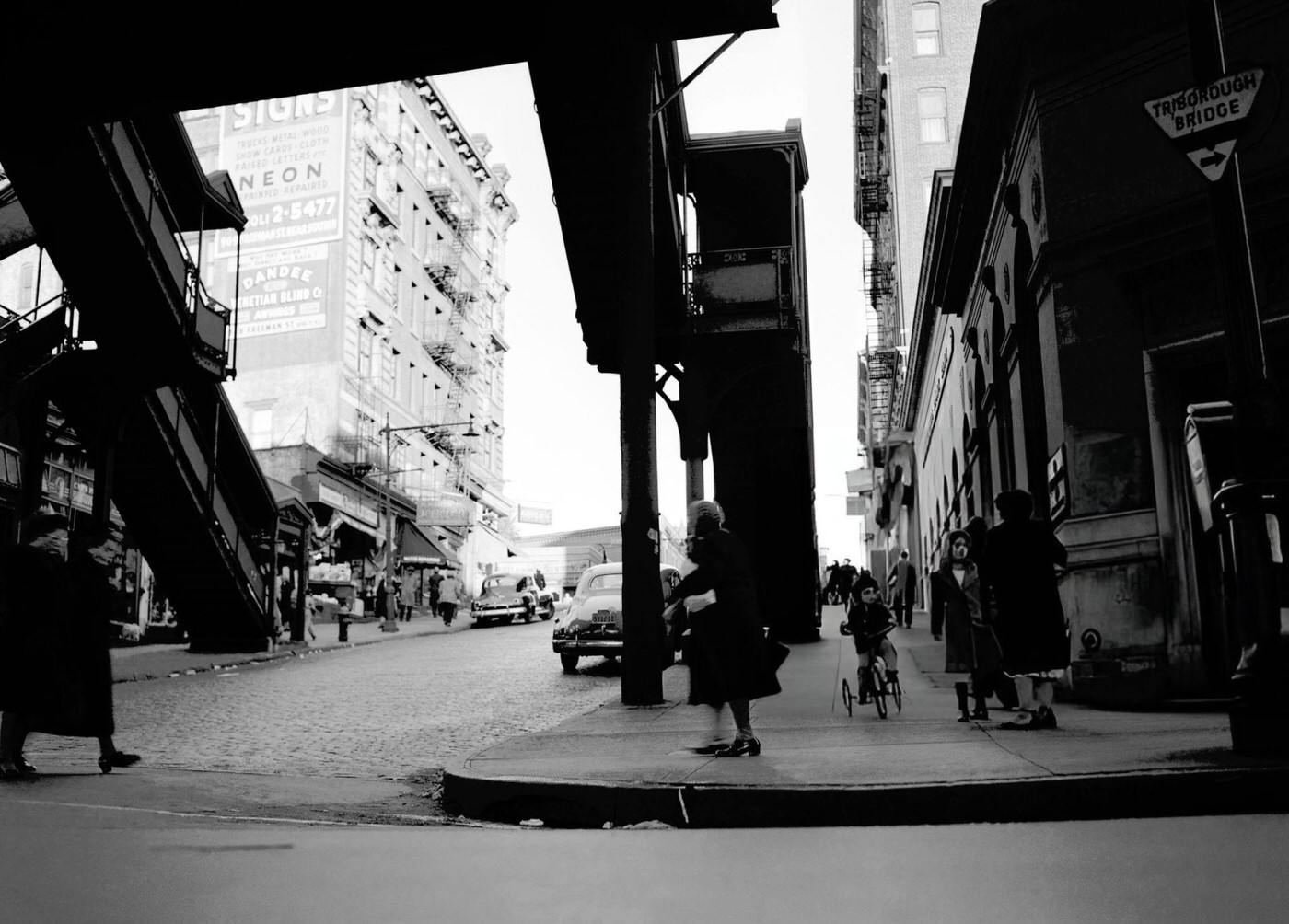

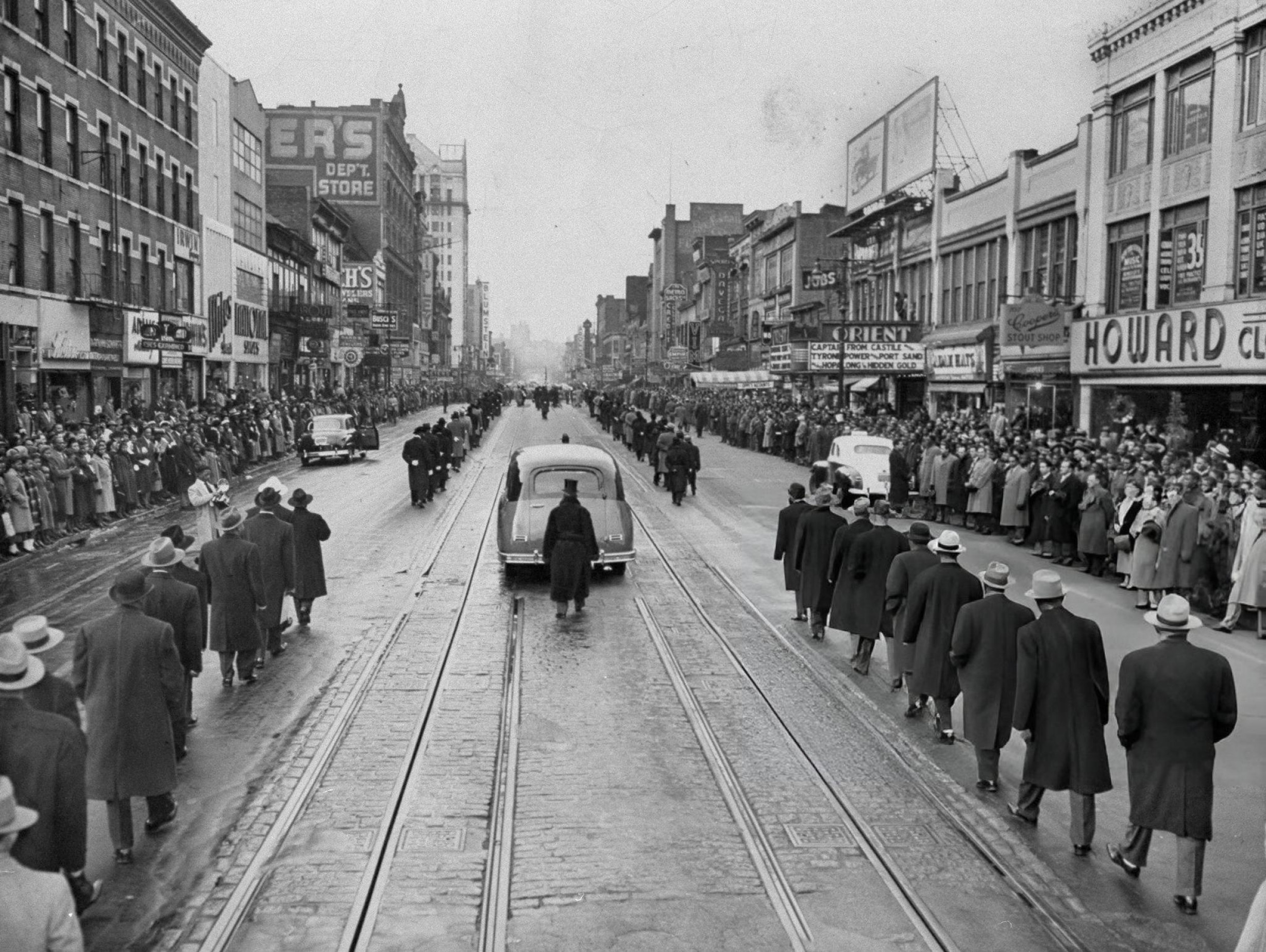

Walking Harlem’s Streets

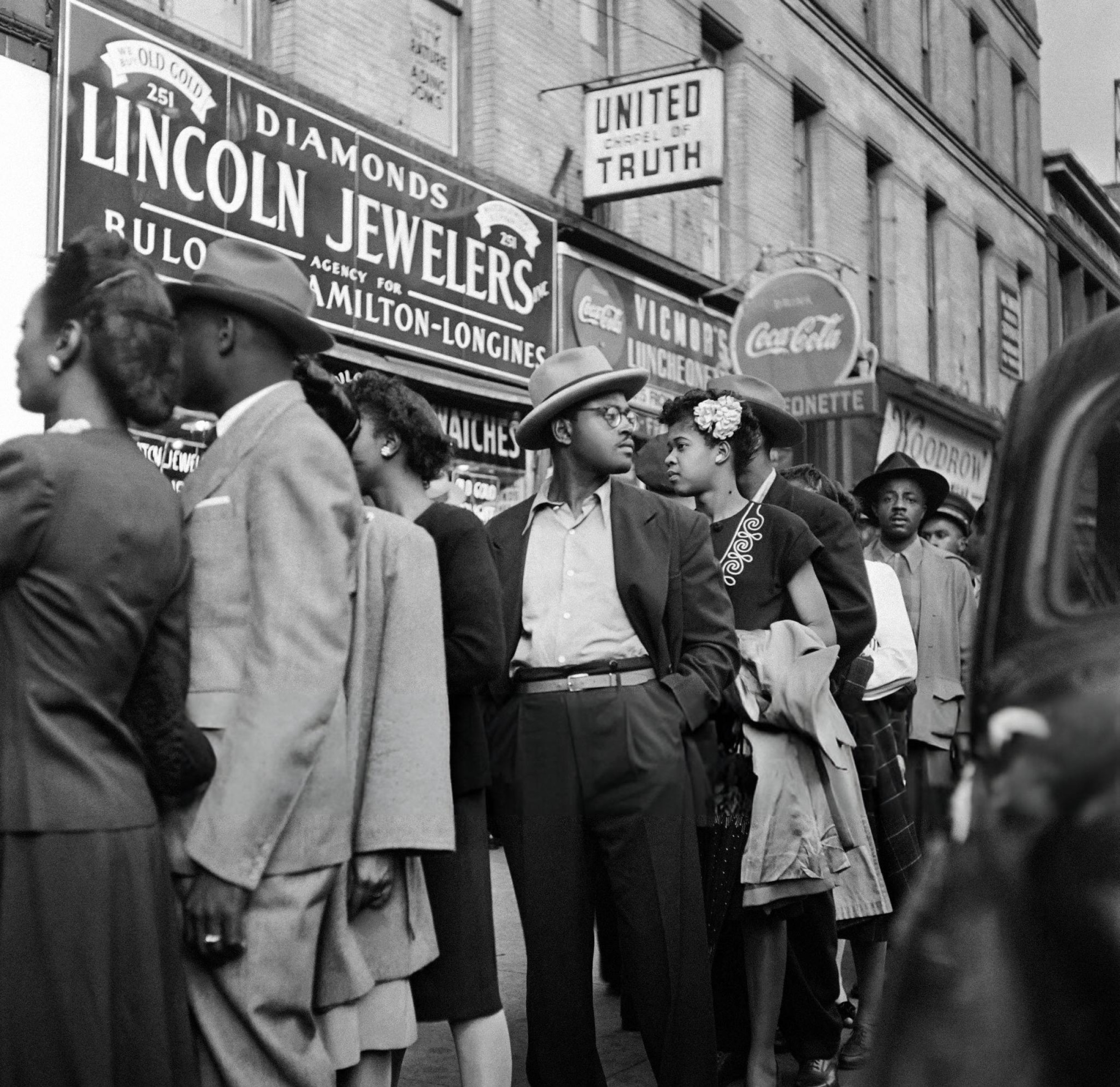

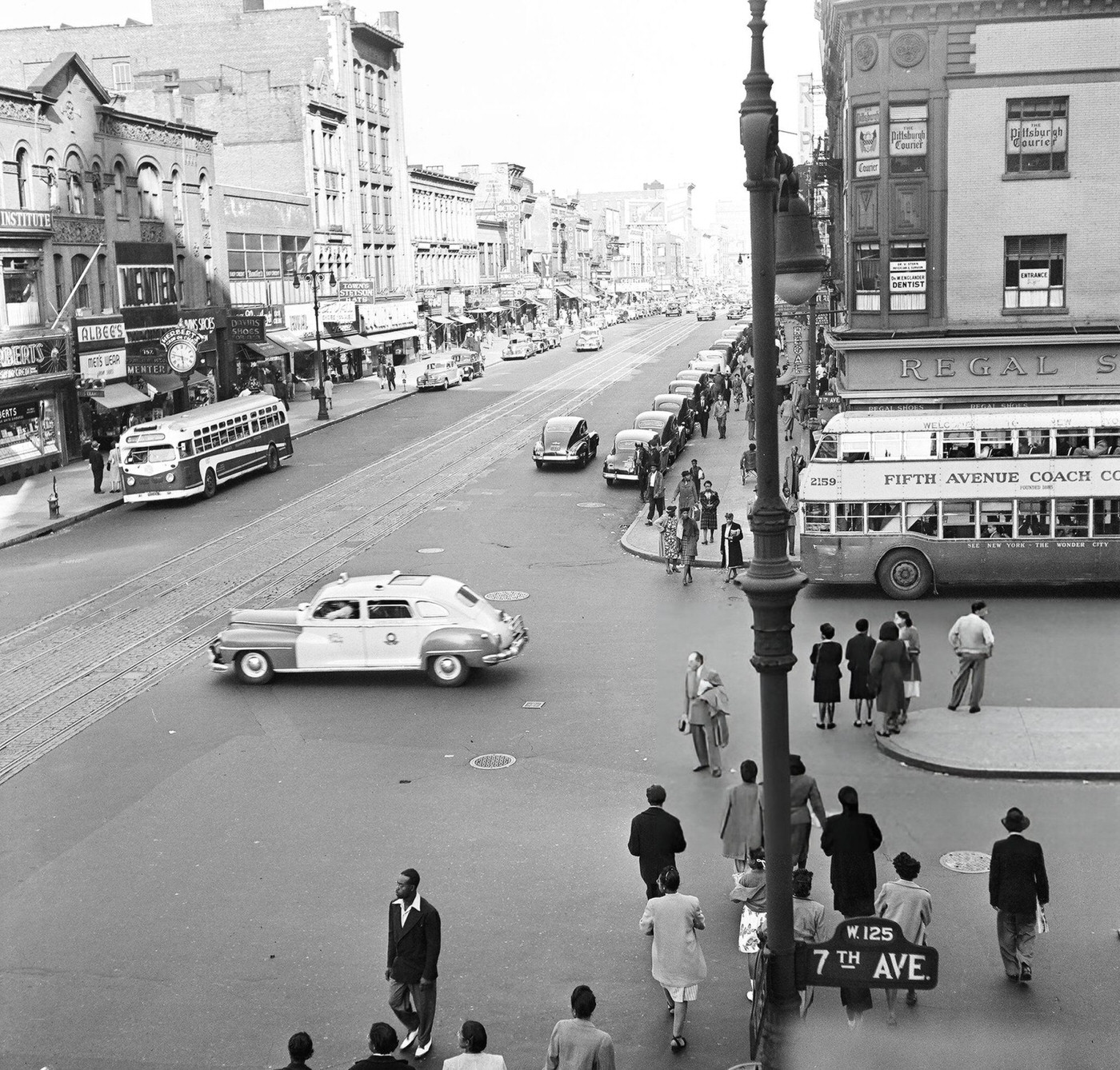

Harlem’s geography in the 1940s was defined by key streets and landmarks that served as centers of community life. 125th Street was the undisputed main artery, a bustling commercial corridor lined with shops, theaters, and businesses. The famous Apollo Theater was a major landmark on this street. Nearby, on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard (formerly Seventh Avenue) between 124th and 125th Streets, stood the imposing Hotel Theresa. After abandoning its discriminatory “whites-only” policy in 1940, the Theresa transformed into the “Waldorf of Harlem”. It became the premier hotel for Black travelers, including prominent politicians, entertainers, athletes, and intellectuals who were barred from downtown establishments. Its dining room and bar buzzed with social activity.

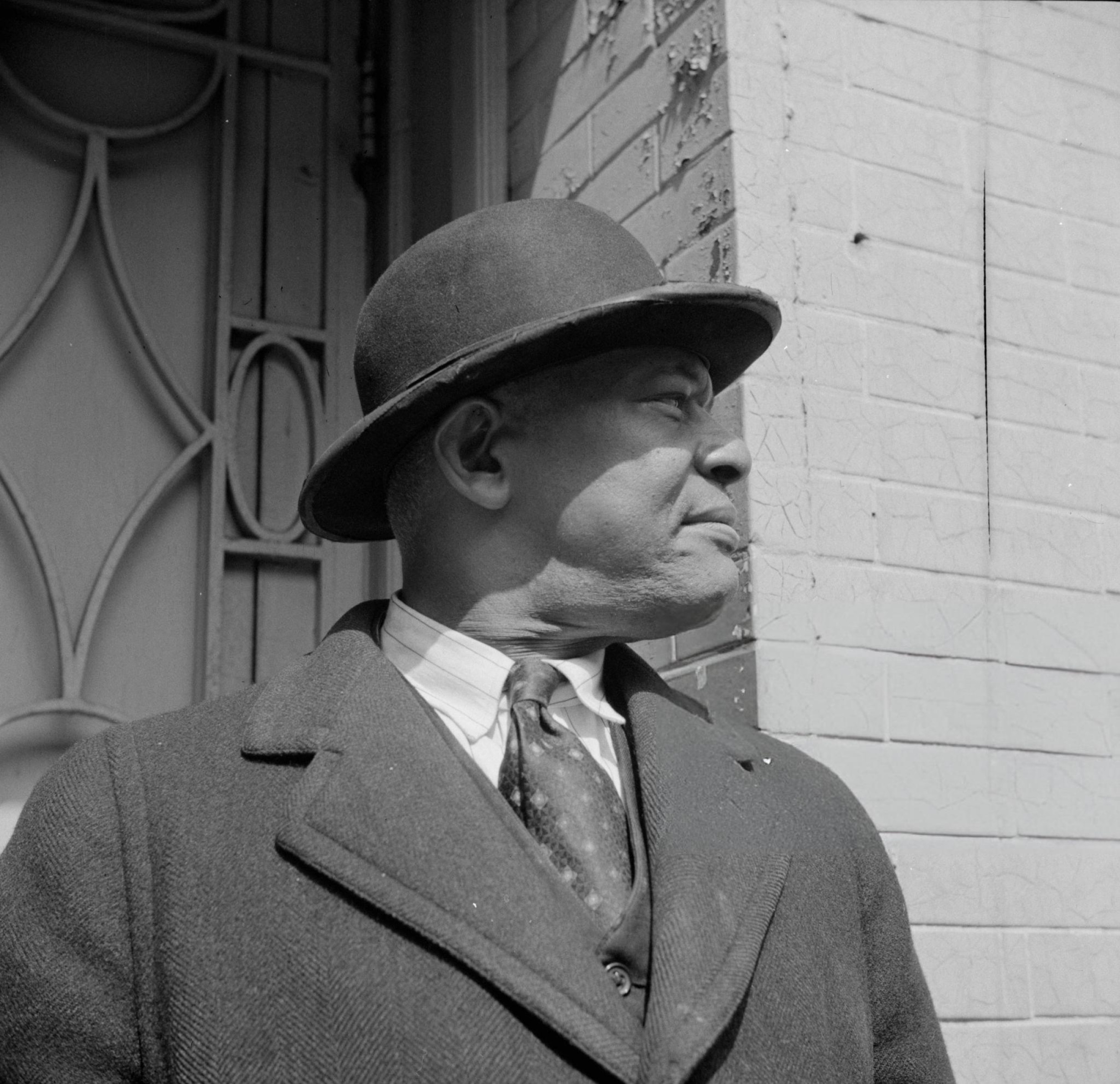

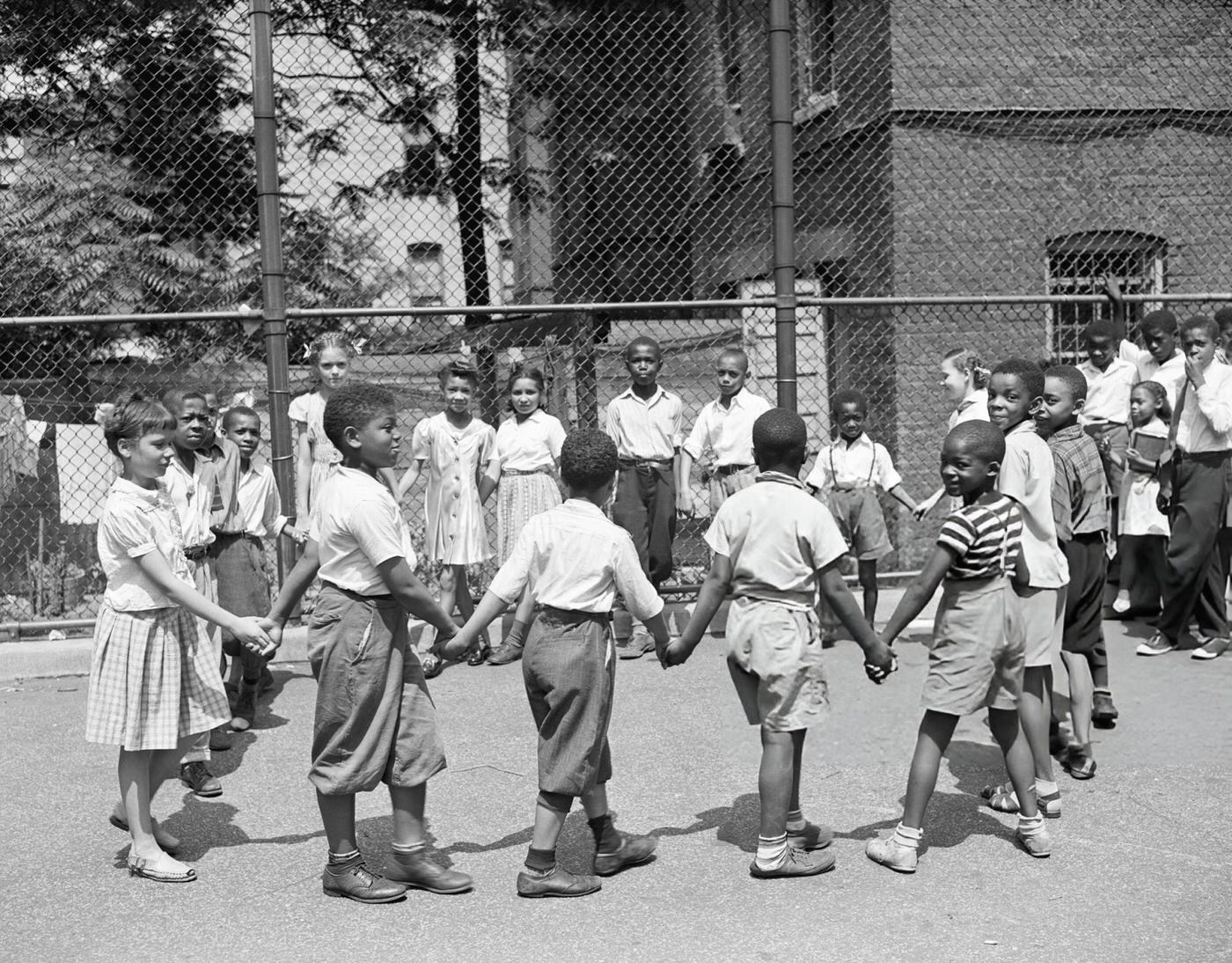

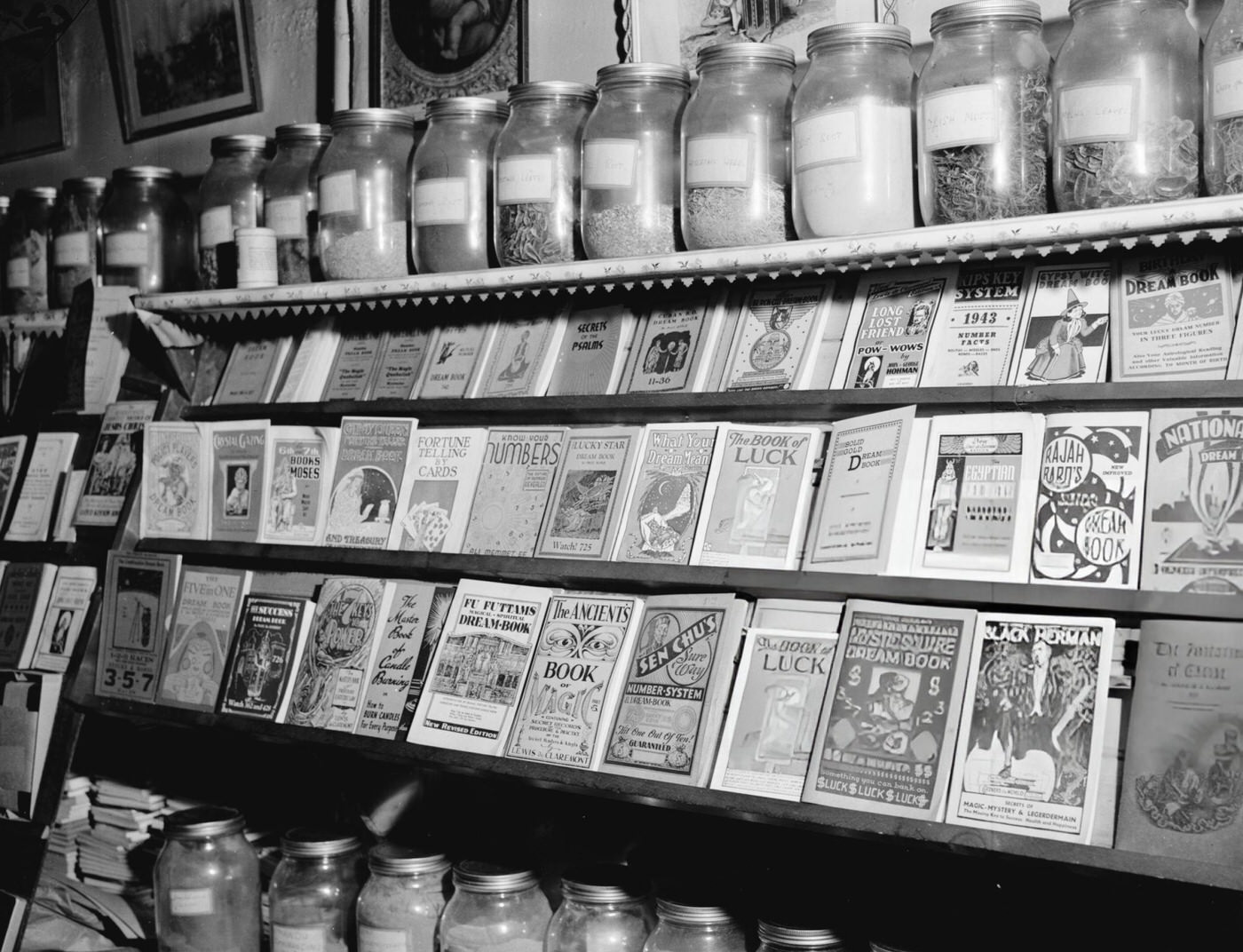

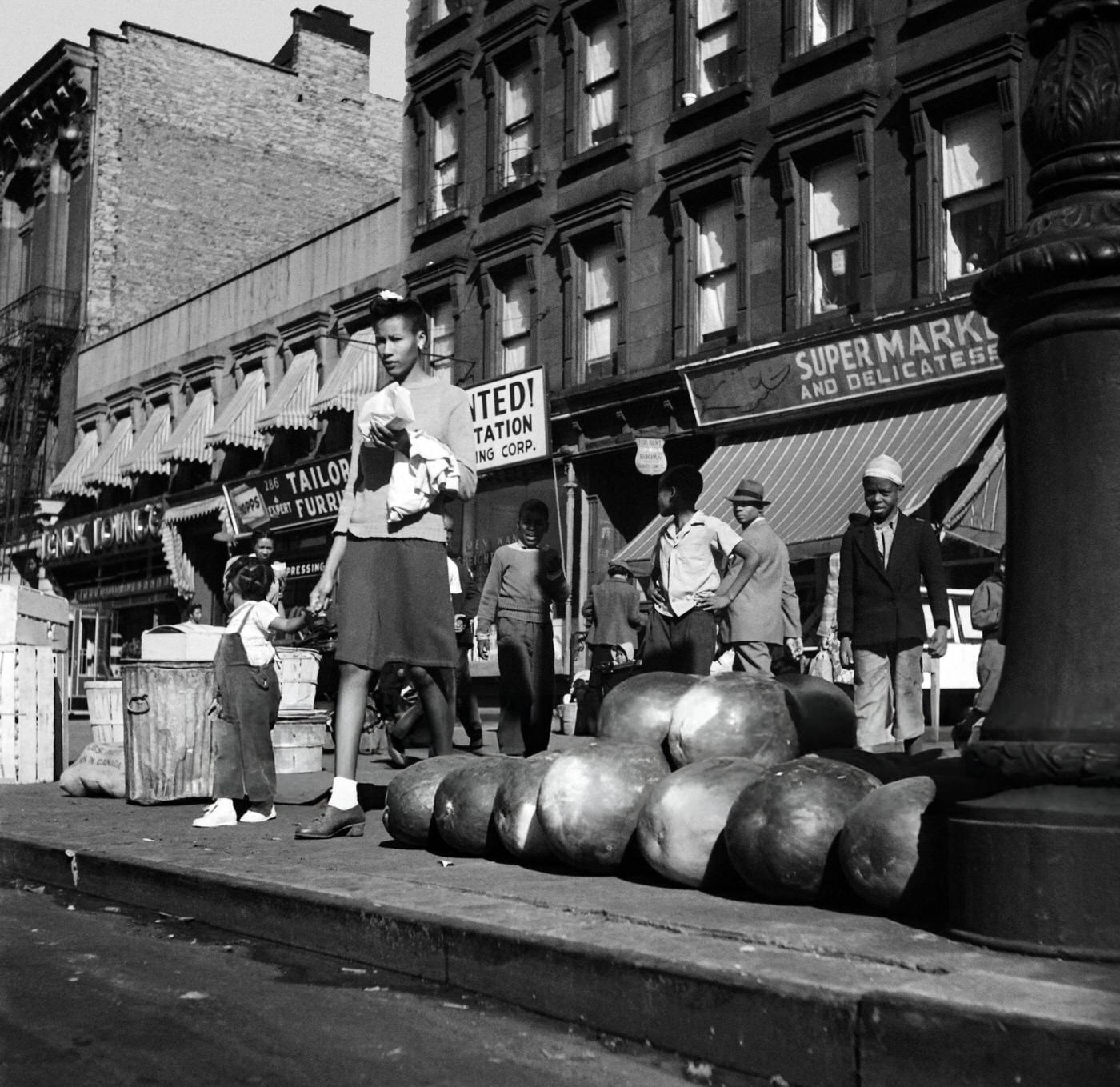

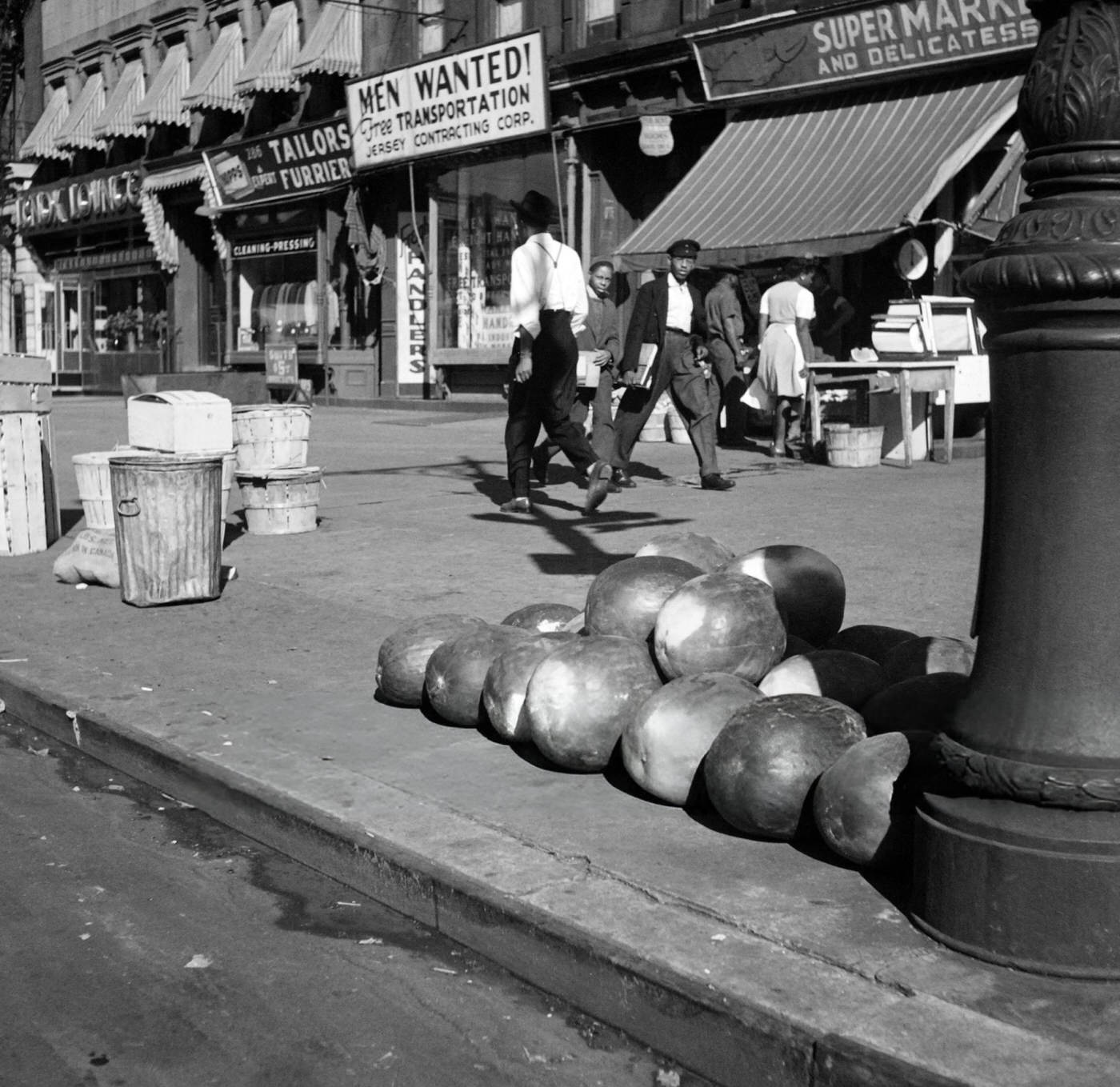

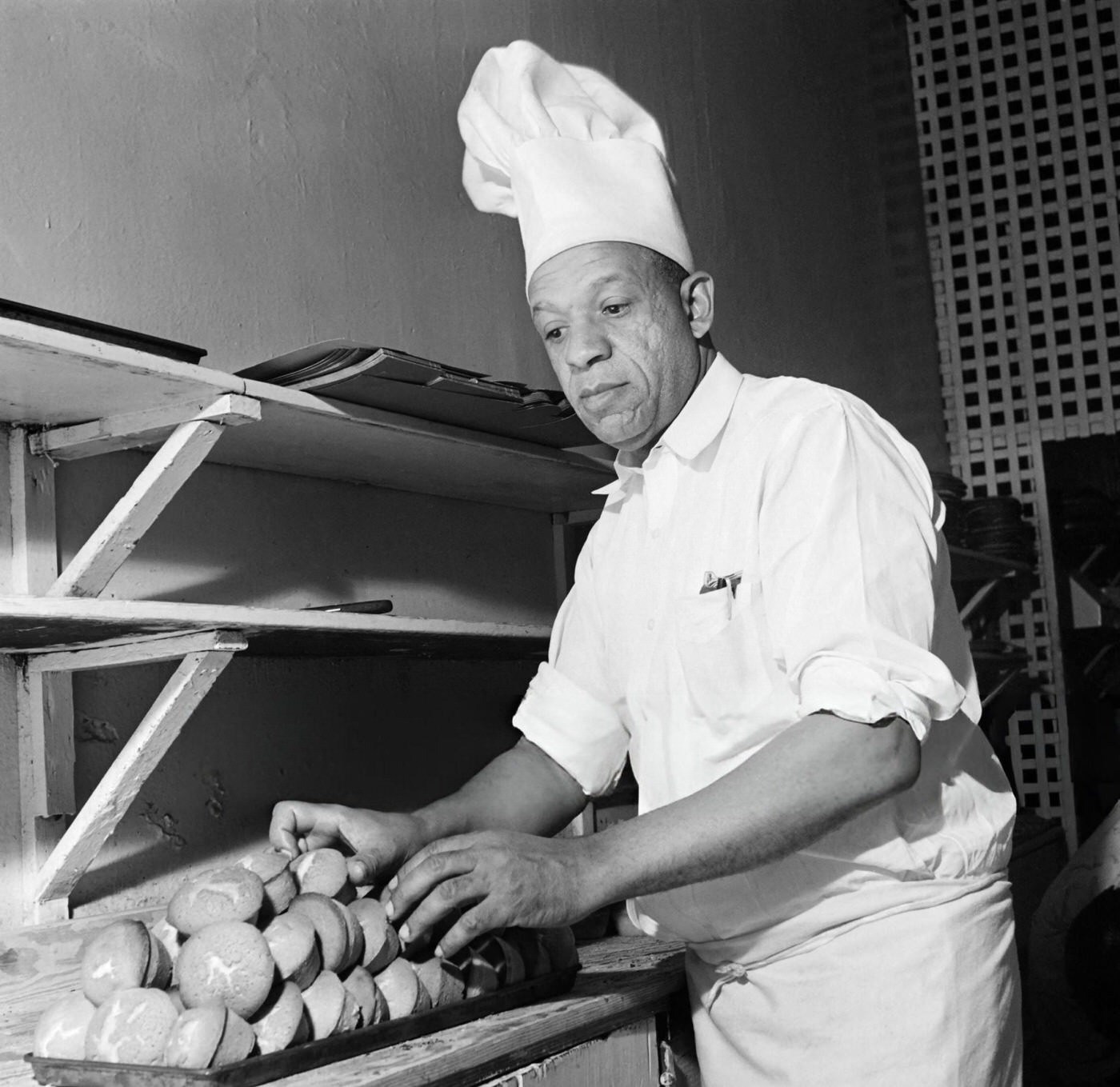

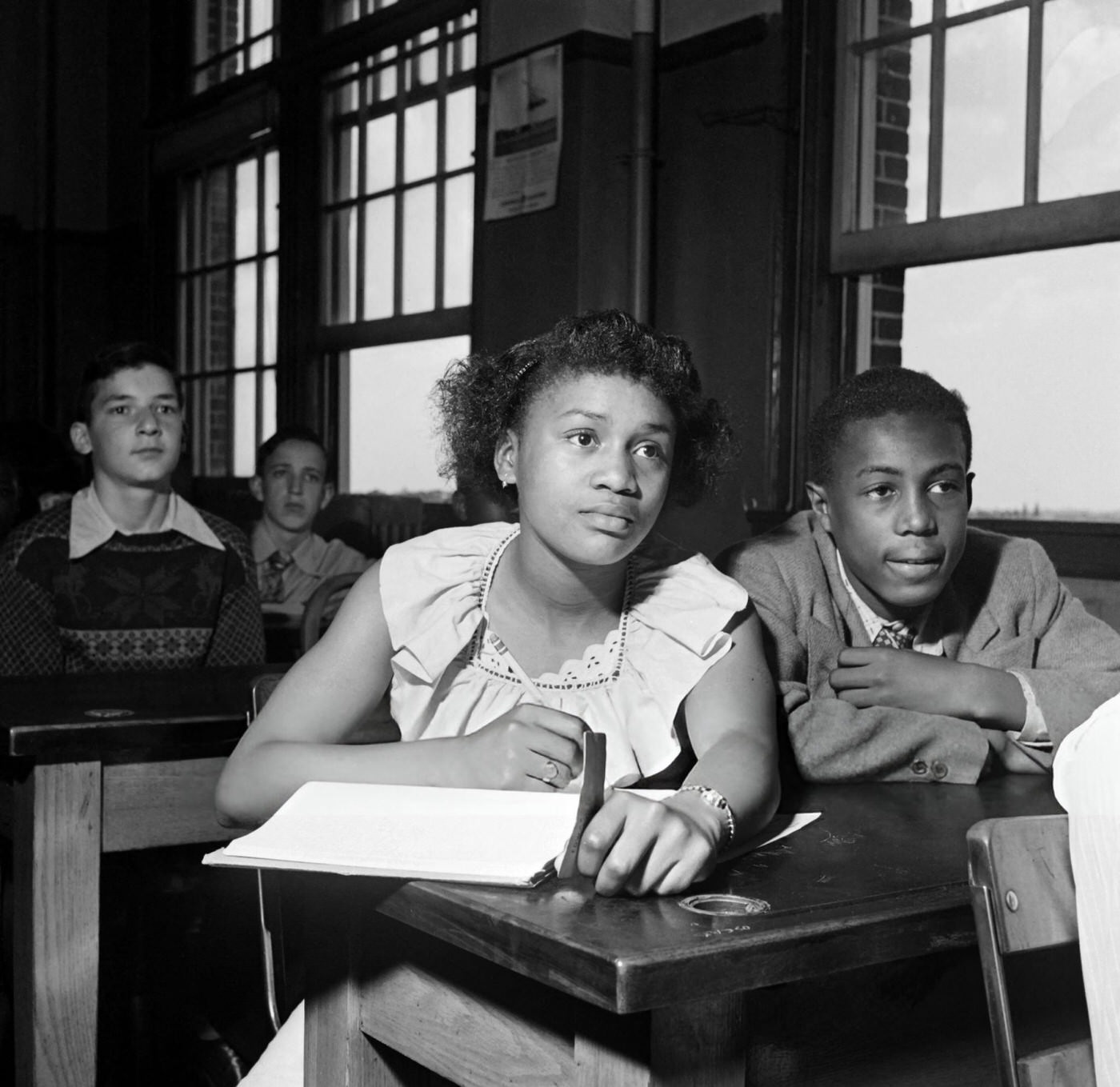

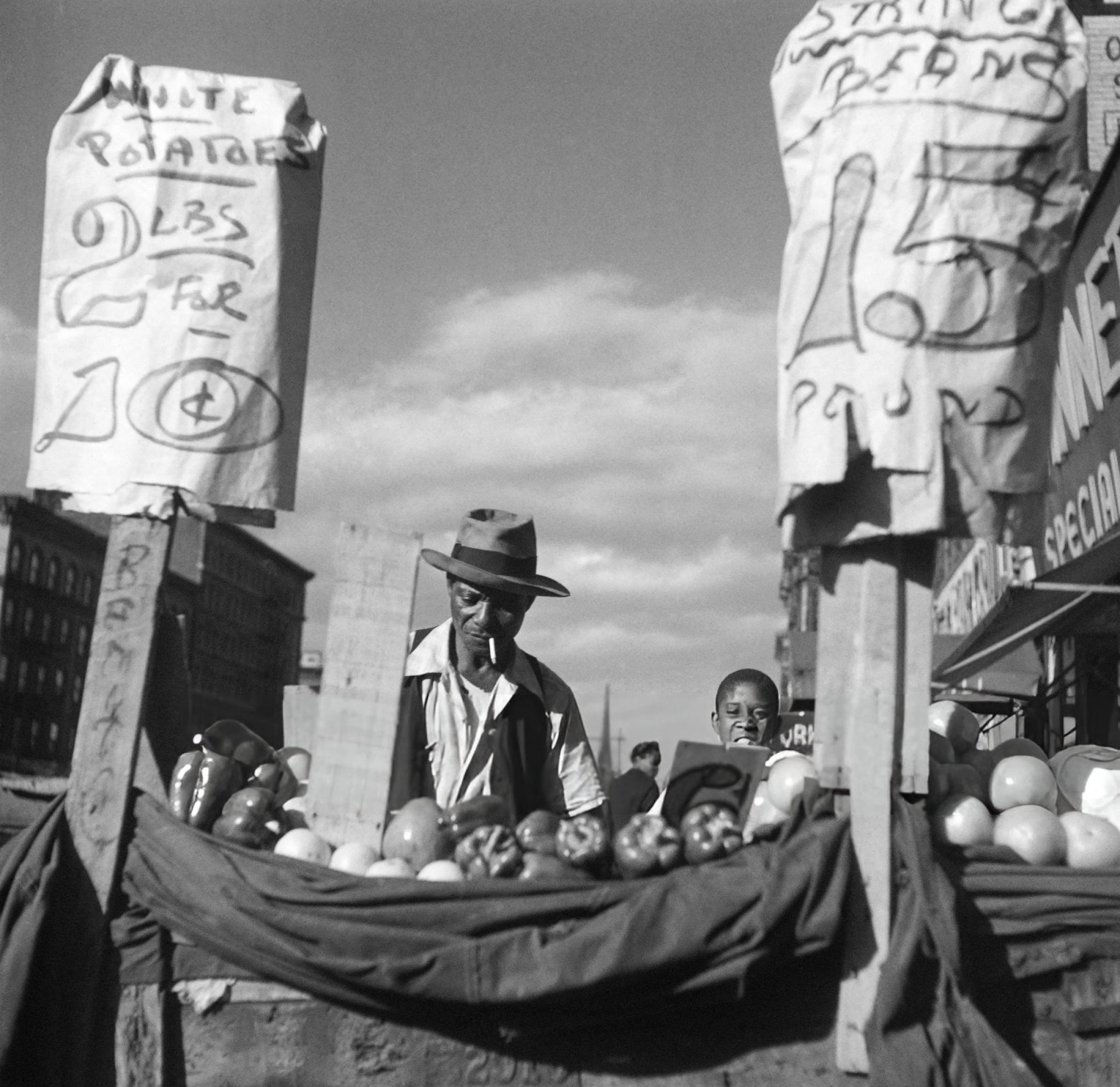

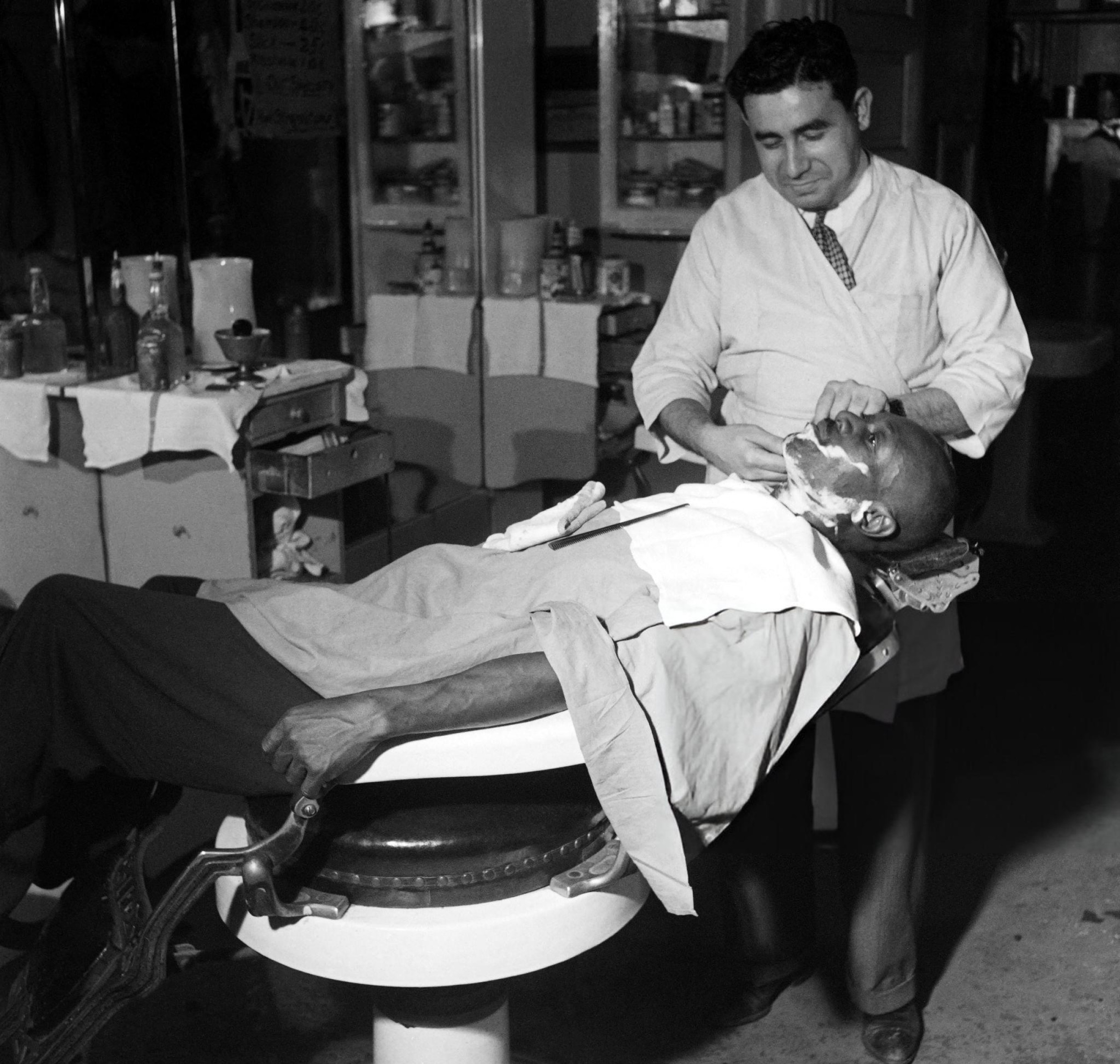

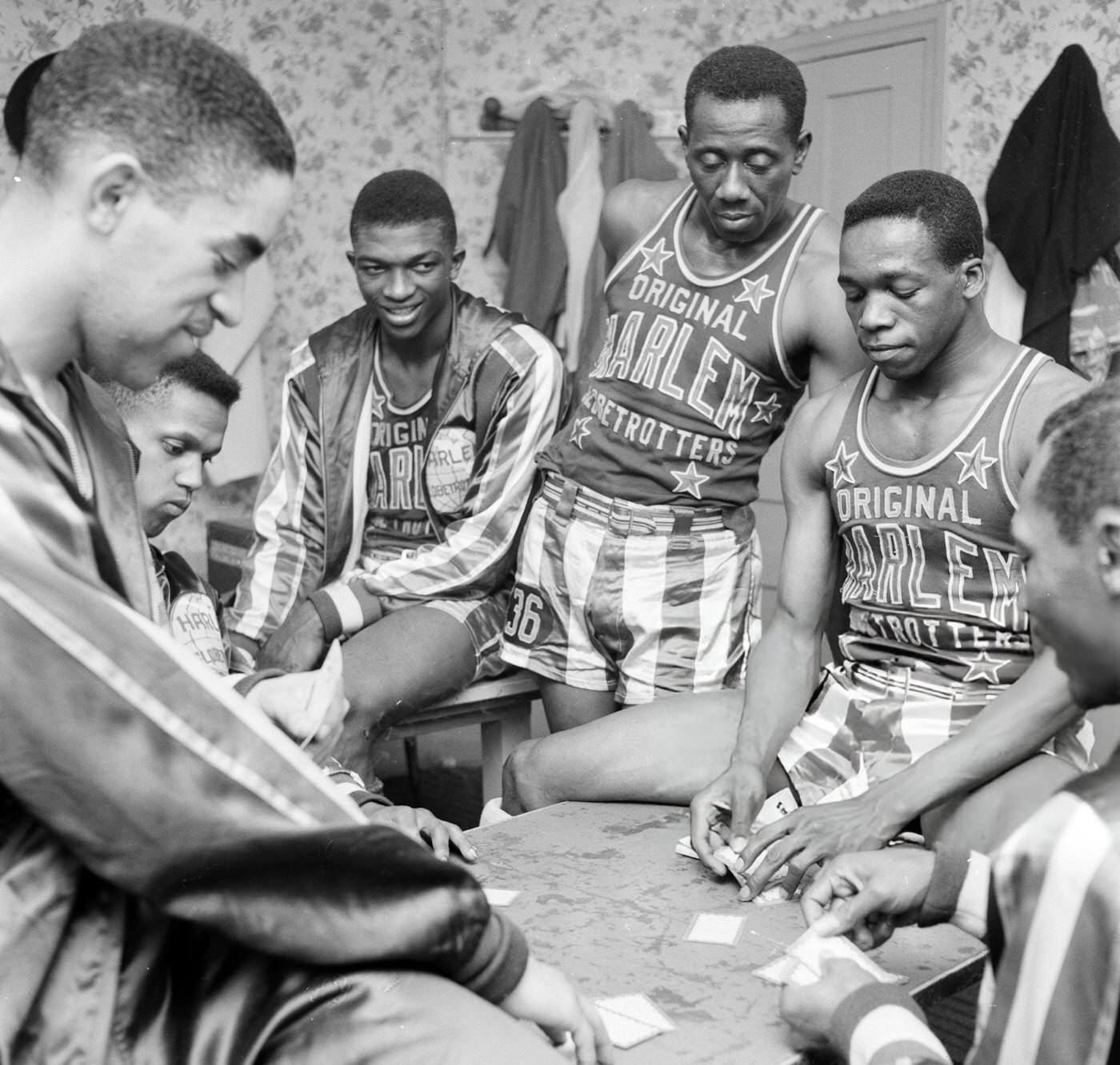

Religious life anchored the community, with Abyssinian Baptist Church, under the leadership of Adam Clayton Powell Jr., being one of the most visible and influential institutions. Jazz lovers congregated at legendary spots like Minton’s Playhouse (housed in the Hotel Cecil on West 118th Street) and the Savoy Ballroom on Lenox Avenue. Street-level views from the era show a neighborhood teeming with life: pedestrians navigating sidewalks, fruit stands on corners, diners and shoeshine booths serving customers, and the distinct architecture of Harlem’s brownstones.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings