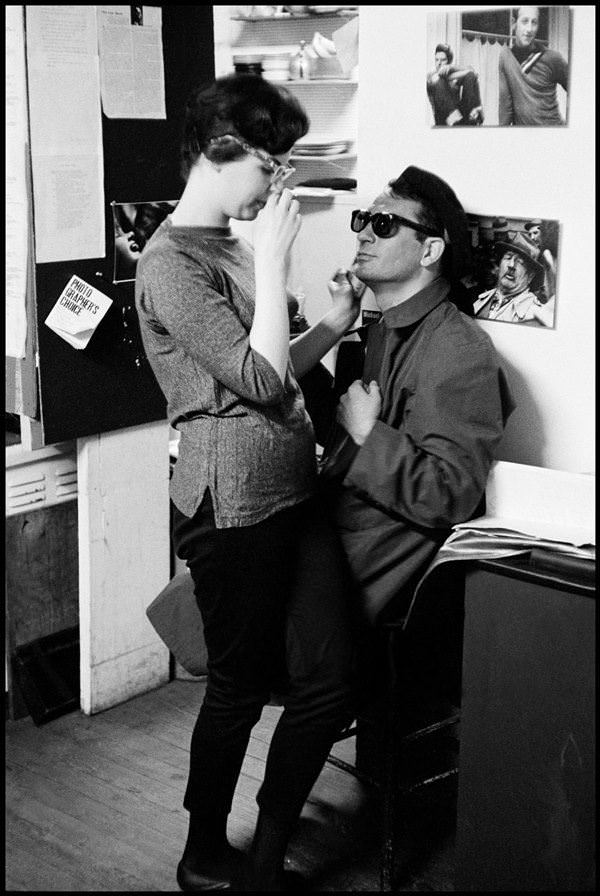

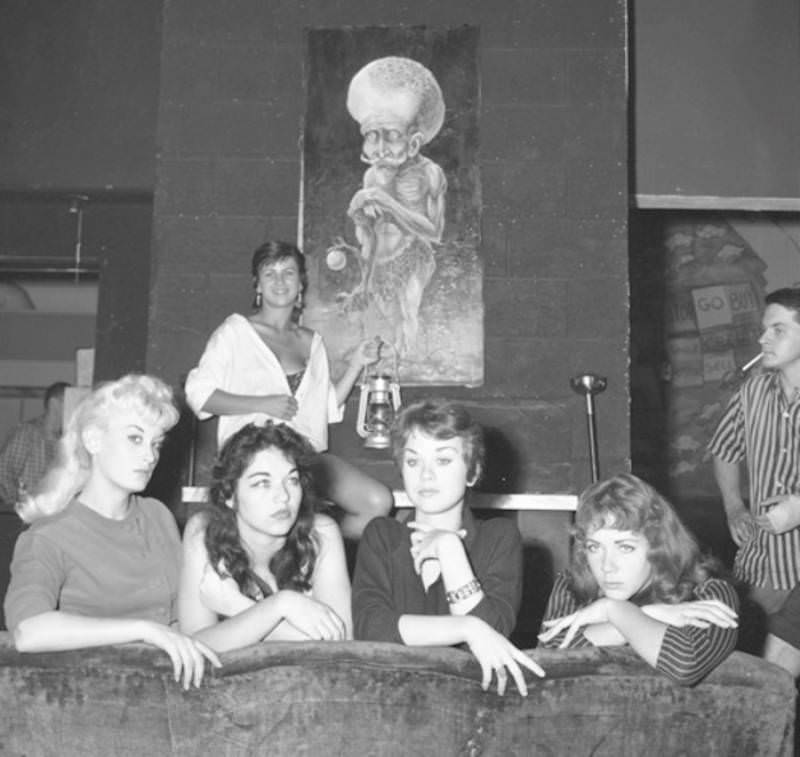

In the 1950s, a new kind of person started to appear in the cafes, bars, and streets of Greenwich Village in New York City. These people wore black turtlenecks, dark sunglasses, and berets. They smoked cigarettes, listened to jazz, and wrote poetry. They were called ‘beatniks’. The name came from the “Beat Generation,” a group of writers and thinkers who rejected traditional American values and created their own culture.

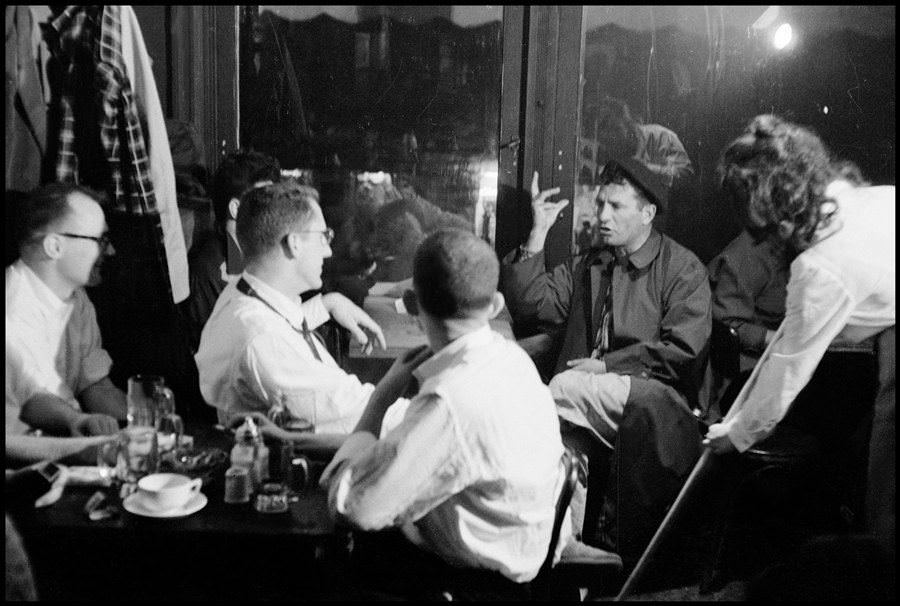

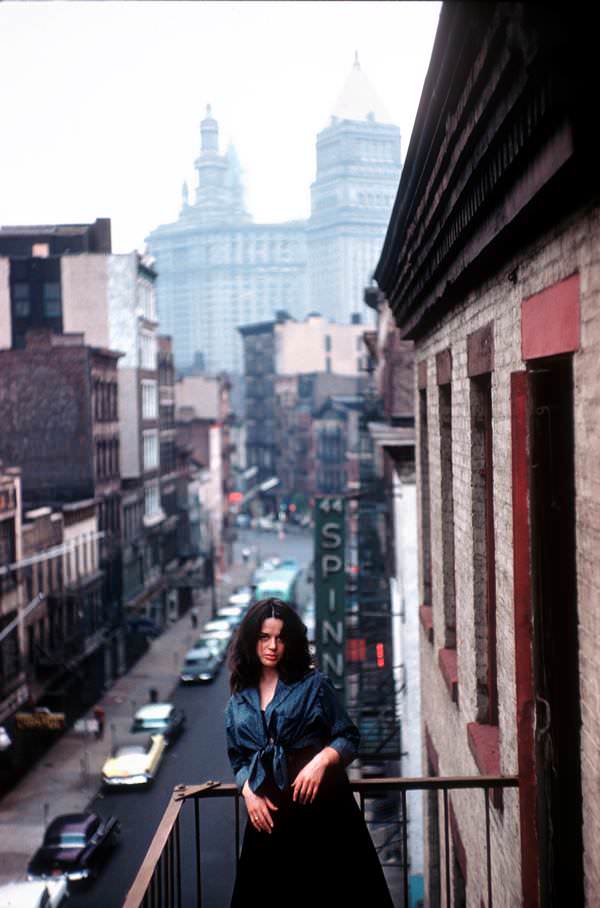

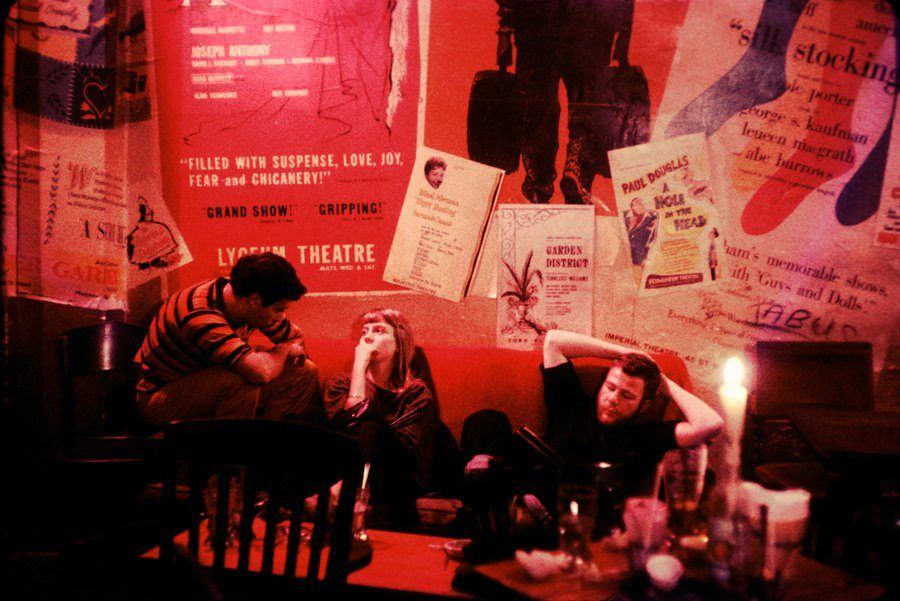

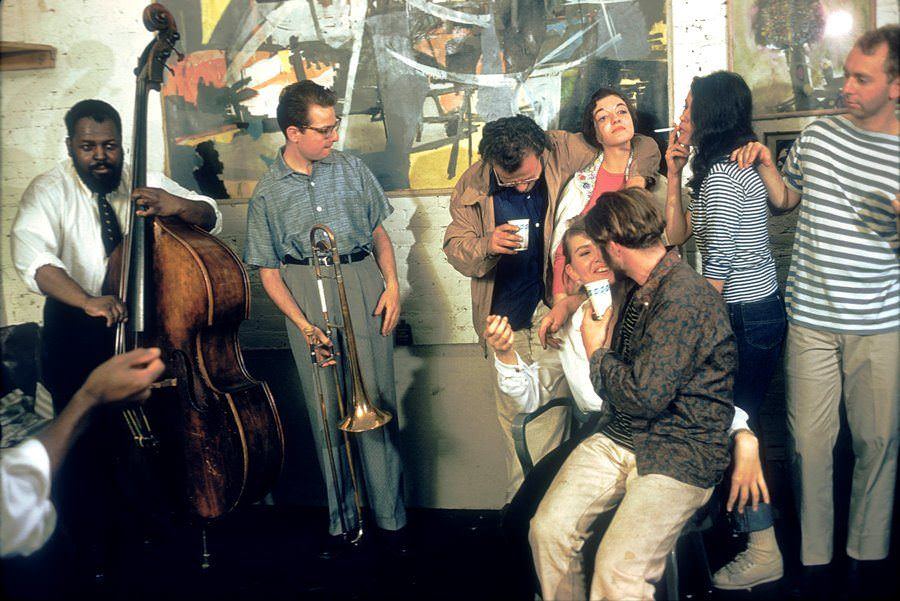

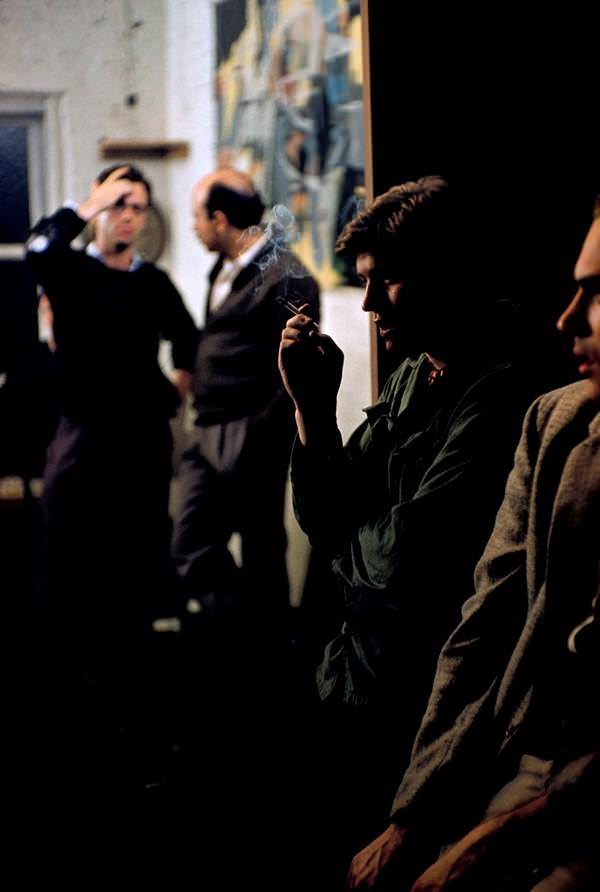

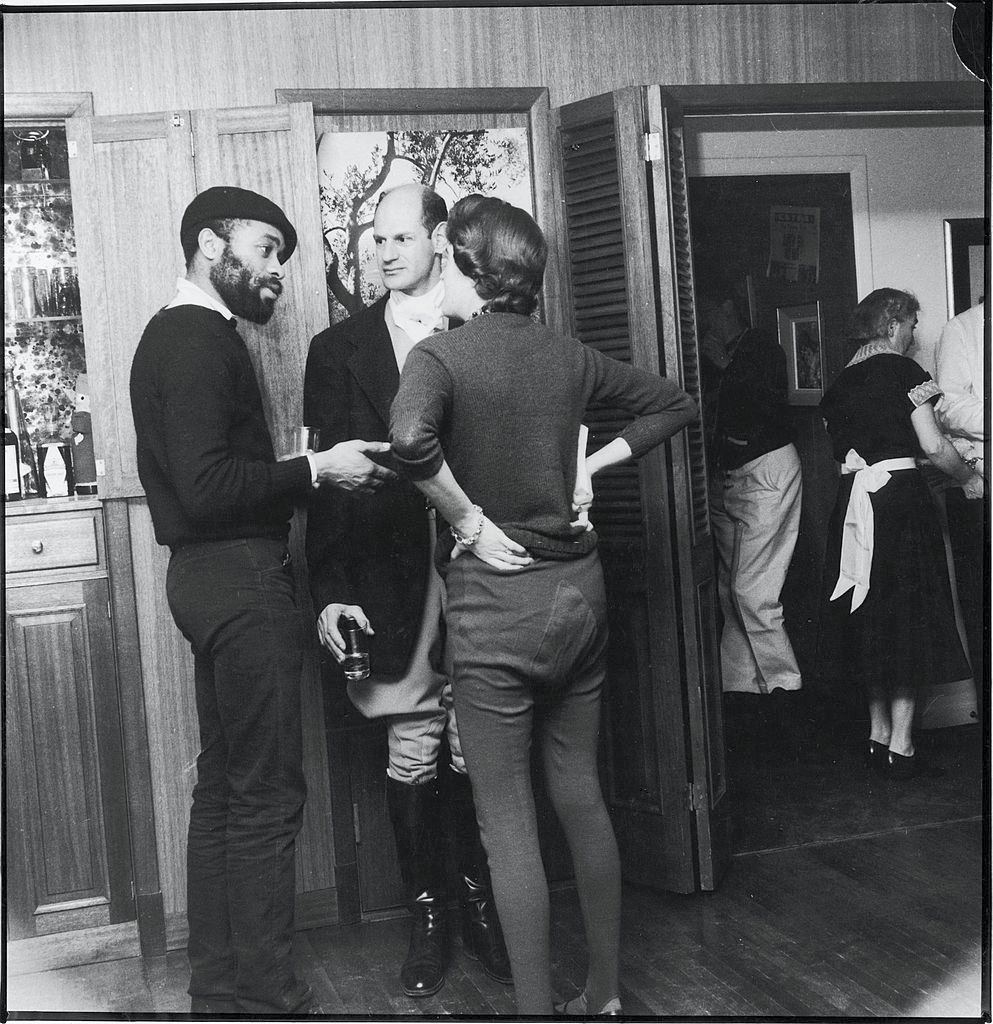

The Beat Movement had started in the late 1940s, but by the 1950s, it had grown into a full lifestyle. Greenwich Village became one of the main centers of the movement. The neighborhood was already known for its artists, musicians, and writers. Rents were low, and people lived in small apartments or shared lofts. The streets were full of bookstores, coffee shops, and art galleries. Beatniks gathered there, talking for hours, sharing ideas, and reading each other’s poems aloud.

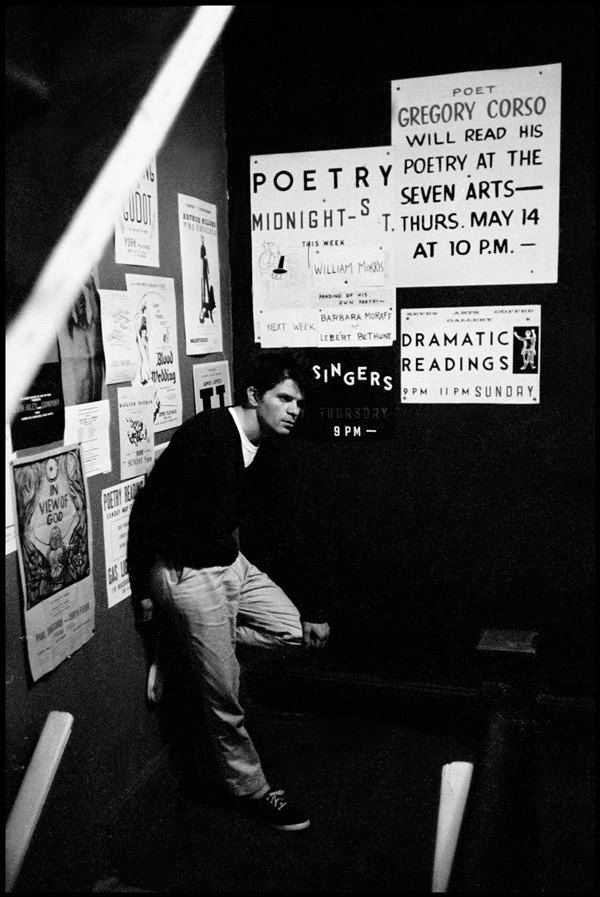

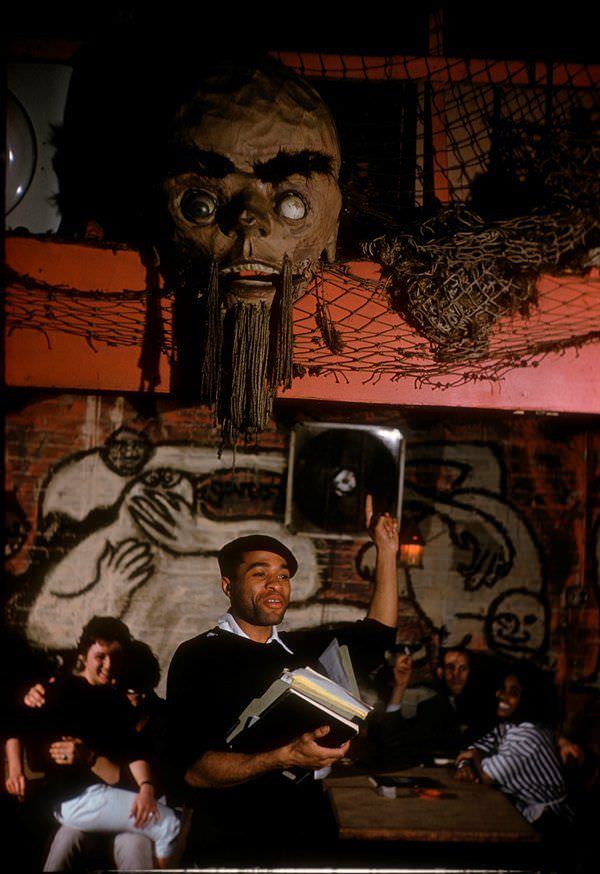

Allen Ginsberg was one of the leading voices of the Beat Generation. In 1955, he read his poem ‘Howl’ for the first time in San Francisco. But much of his life and work were tied to New York. He had studied at Columbia University and stayed in the city often. ‘Howl’ was filled with images of madness, freedom, drugs, and pain. It shocked many people, but it also caught the attention of a growing group of readers who felt left out by regular society. Ginsberg often read in New York cafes, where audiences sat cross-legged on the floor, snapping fingers in approval instead of clapping.

Read more

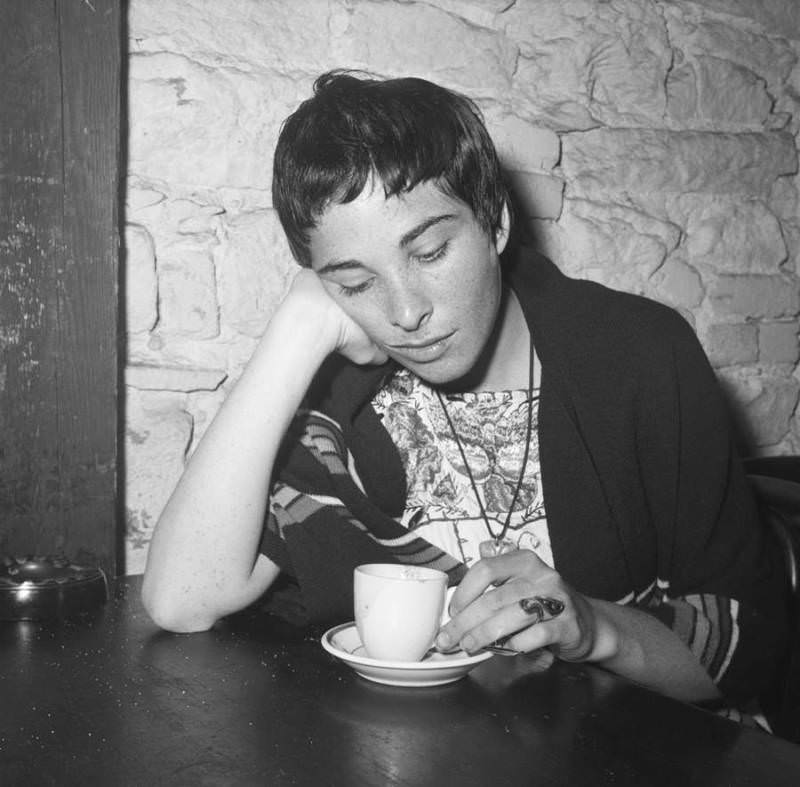

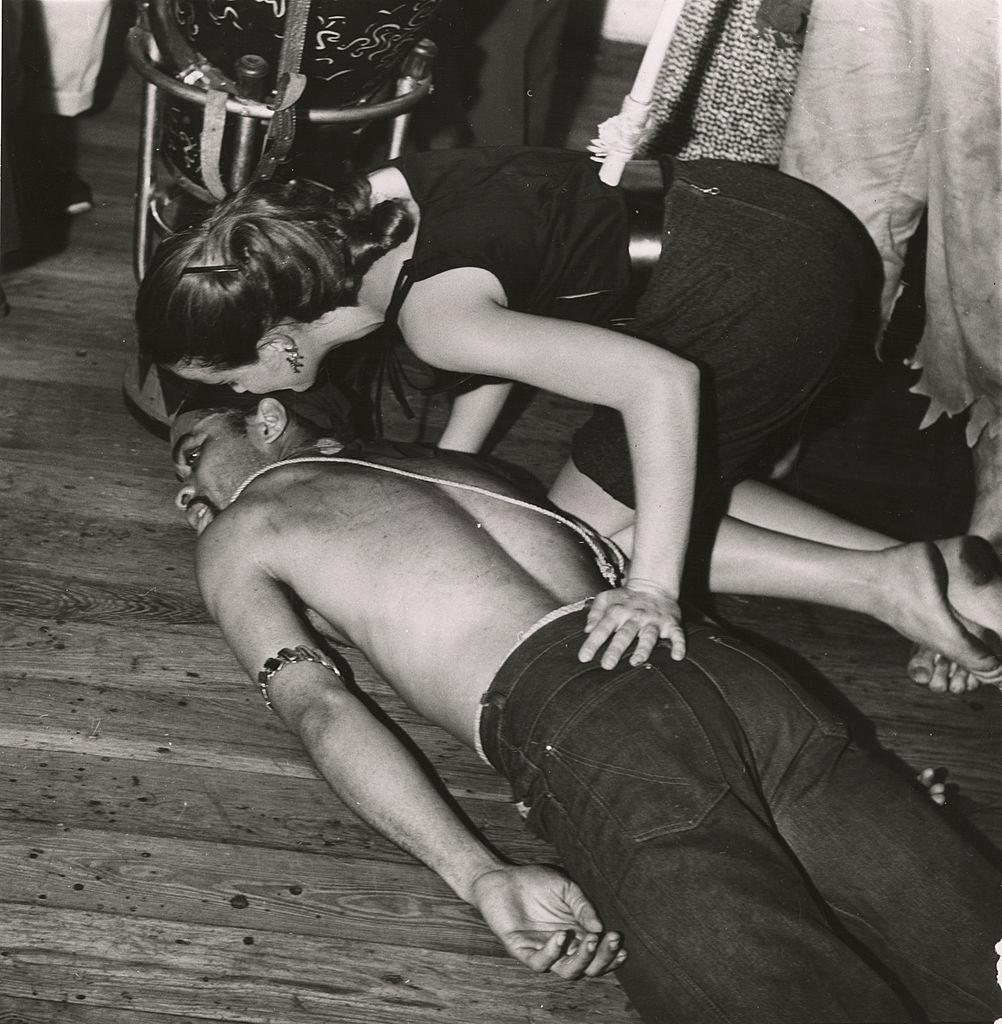

The beatniks didn’t believe in working just for money. Many took simple jobs, like waiting tables, painting houses, or selling books. They didn’t want careers, houses in the suburbs, or cars. They saw those things as part of a fake lifestyle. They wanted truth, art, and experience. They often wrote poems late at night, typed stories on cheap paper, or painted on scraps of wood and canvas.

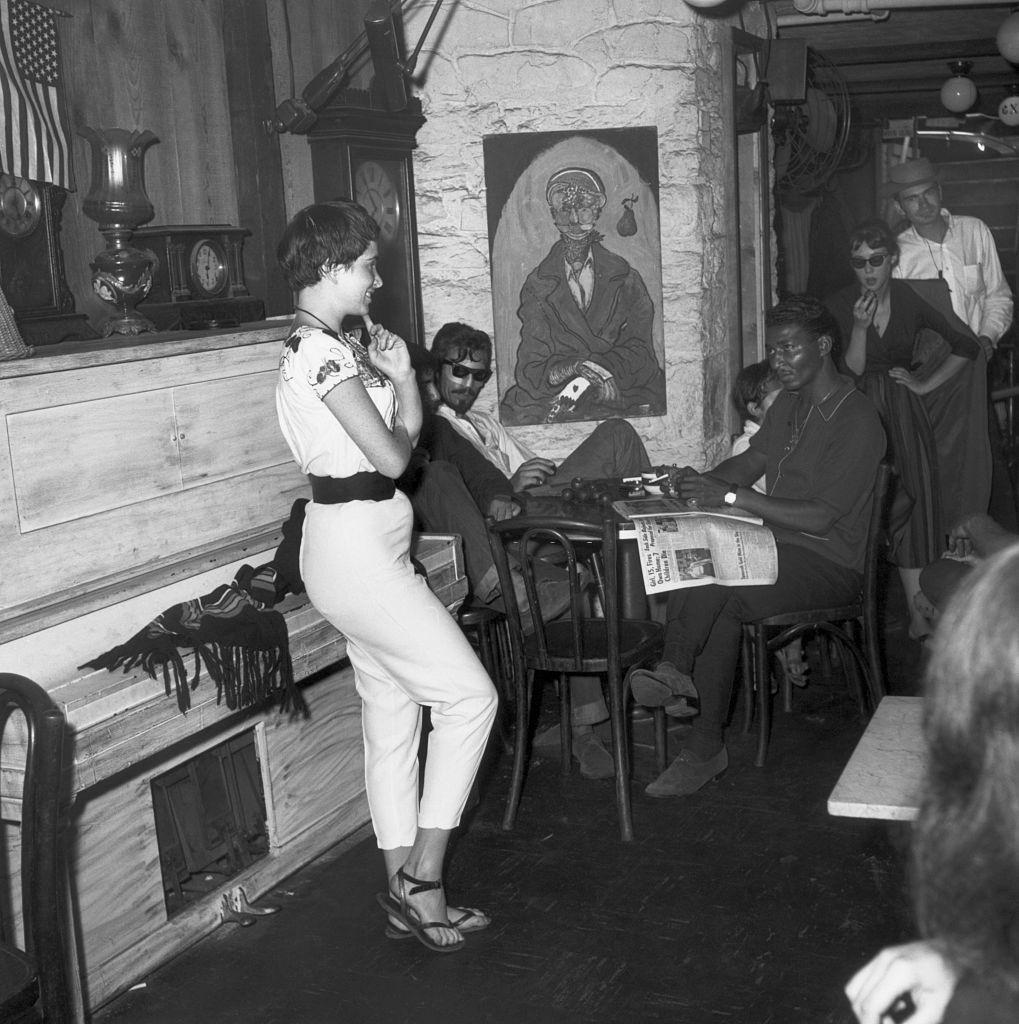

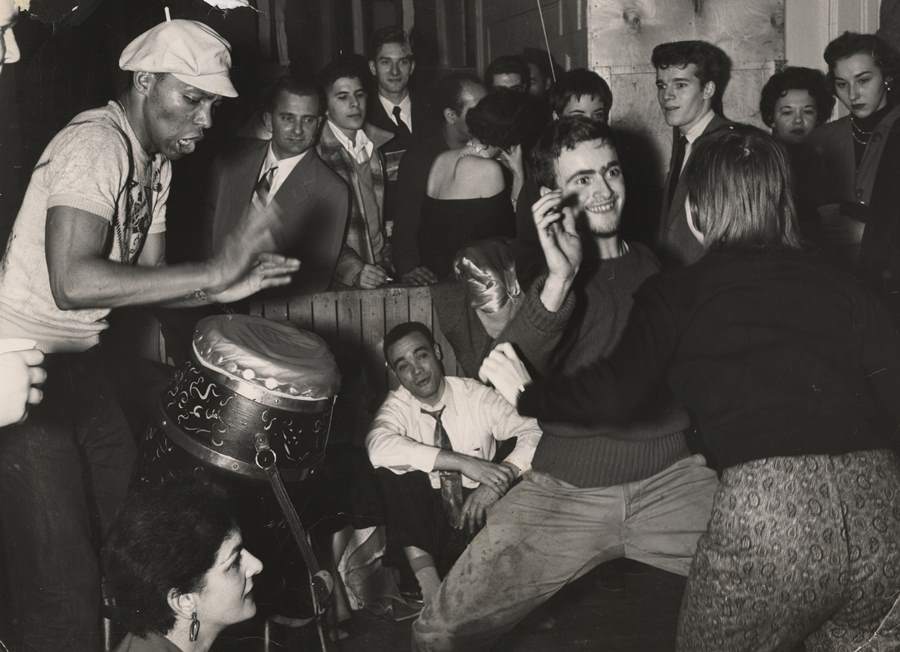

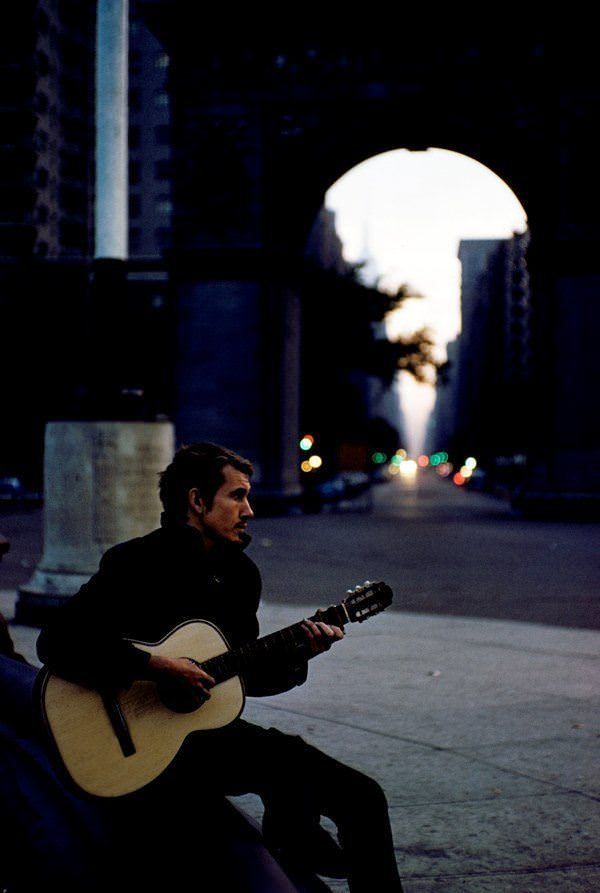

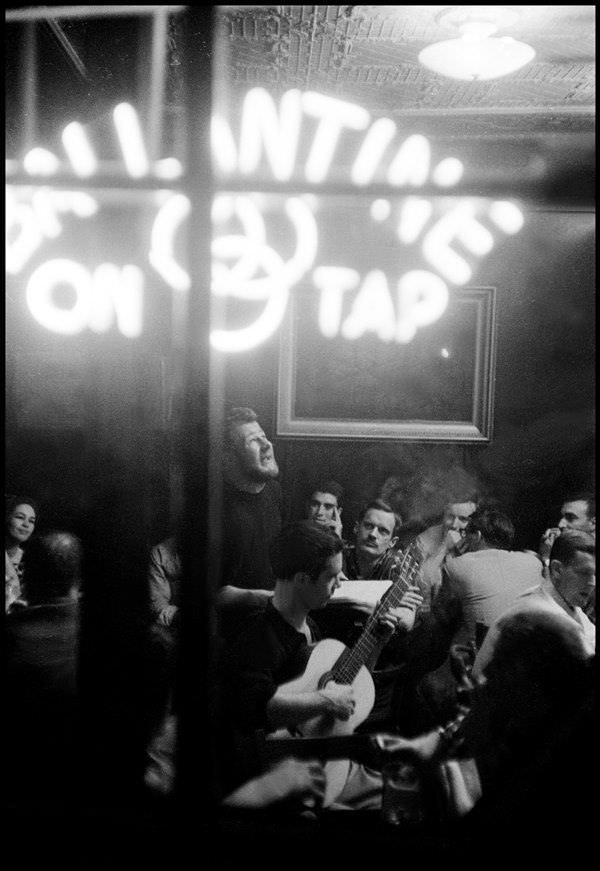

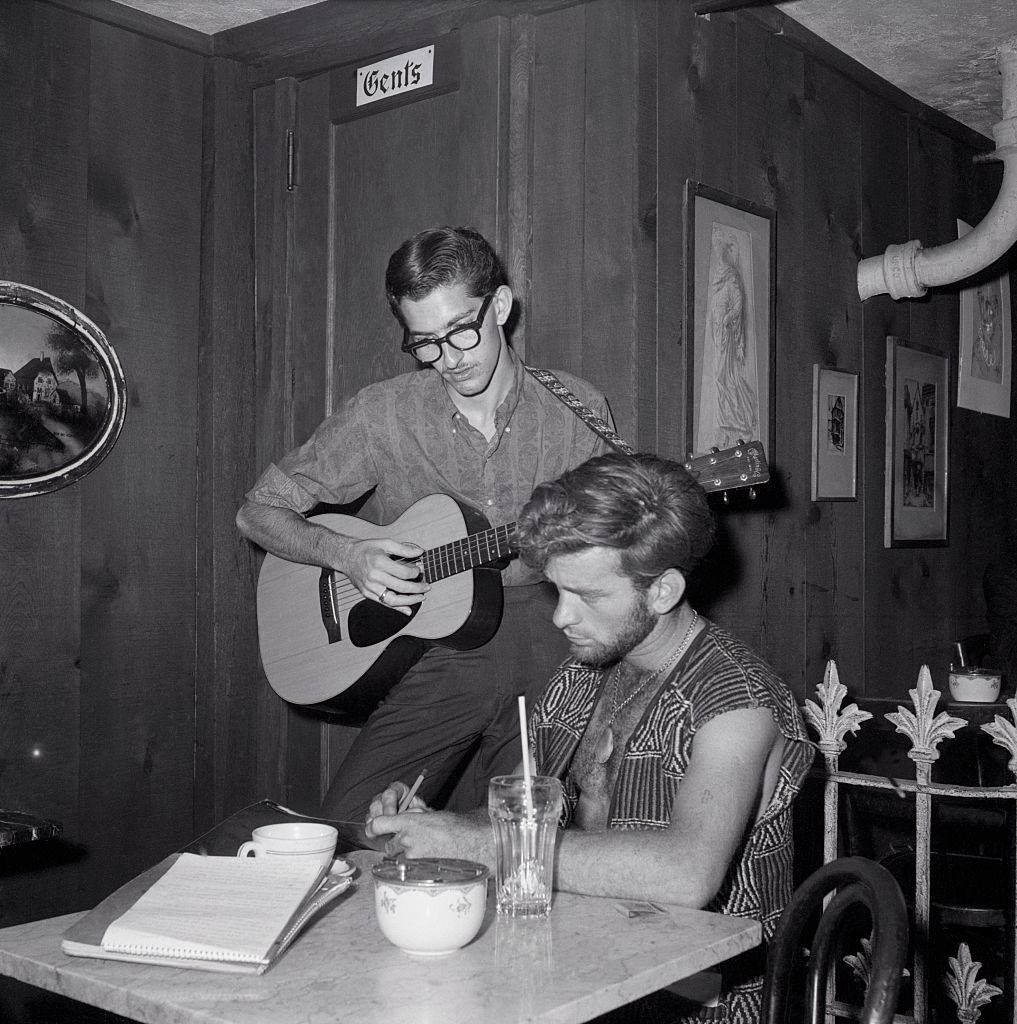

Jazz was central to the beatnik world. Clubs in Greenwich Village like the Village Vanguard and Café Bohemia hosted live jazz almost every night. Beatniks loved the sounds of saxophones and drums, especially when the music was wild and unpredictable. Jazz musicians and beat poets shared a rhythm. Both used improvisation and spoke from deep emotion. Poets sometimes read aloud while jazz played behind them, letting the music carry the mood.

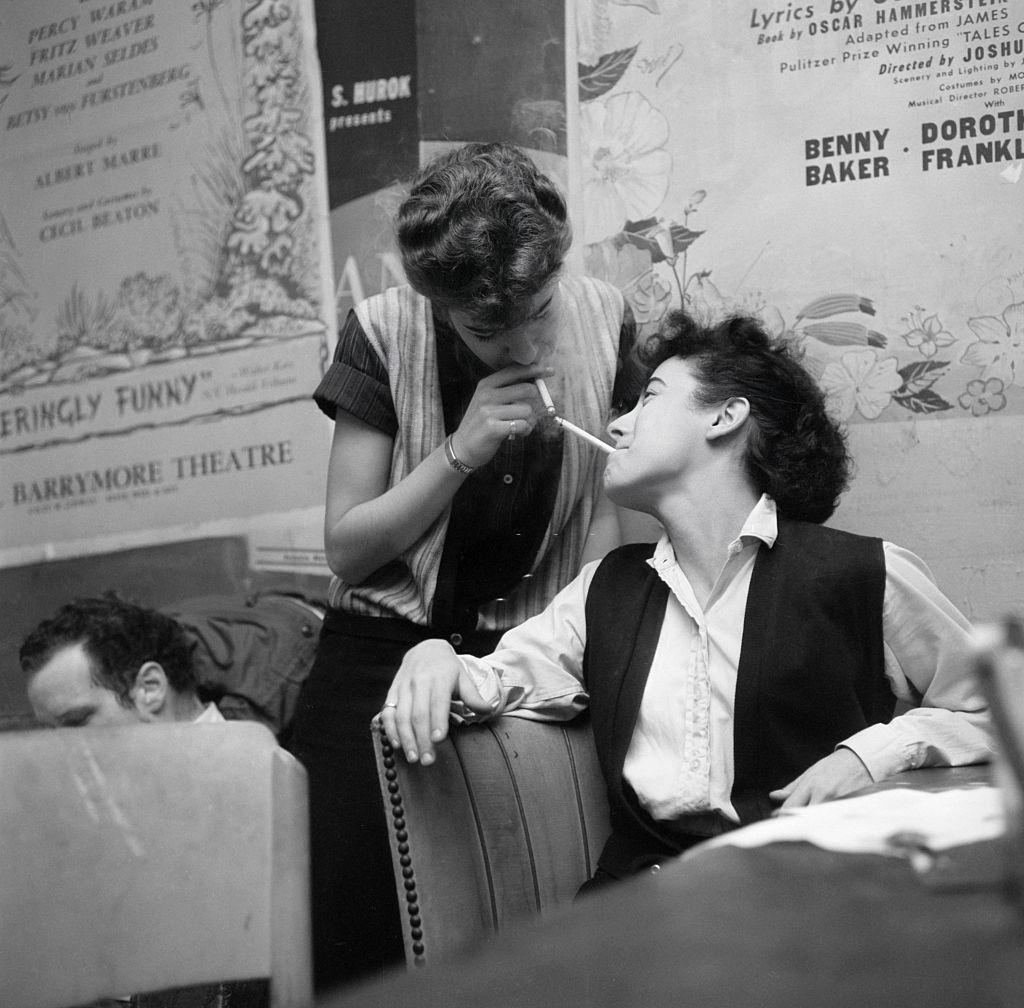

Drug use was common among beatniks. Marijuana, Benzedrine, and later LSD were all used to expand the mind or escape regular thinking. Many believed that breaking down normal thought patterns helped open the path to art or truth. Ginsberg and others wrote openly about their drug experiences. This attracted both interest and criticism. Police raided some beat hangouts. Writers were arrested for drug use or obscene content. Still, the movement grew.

Books like ‘Naked Lunch’ by William Burroughs and ‘On the Road’ by Jack Kerouac were passed around beat circles. These books were full of fast language, strange images, and wild travels. Kerouac, like Ginsberg, had spent time in New York. He wrote much of ‘On the Road’ while living in the city. His writing was fast and full of energy. He typed entire novels on single rolls of paper, never stopping to edit. Beatniks admired this raw, honest style.

Many beatniks were interested in Eastern religions, especially Zen Buddhism. They liked the idea of clearing the mind, living in the moment, and finding peace outside of material things. Some joined meditation groups. Others read Zen texts or practiced quiet walks through the city. A few even traveled to Japan to study more deeply. These teachings fit with the beat belief in personal freedom and spiritual searching.

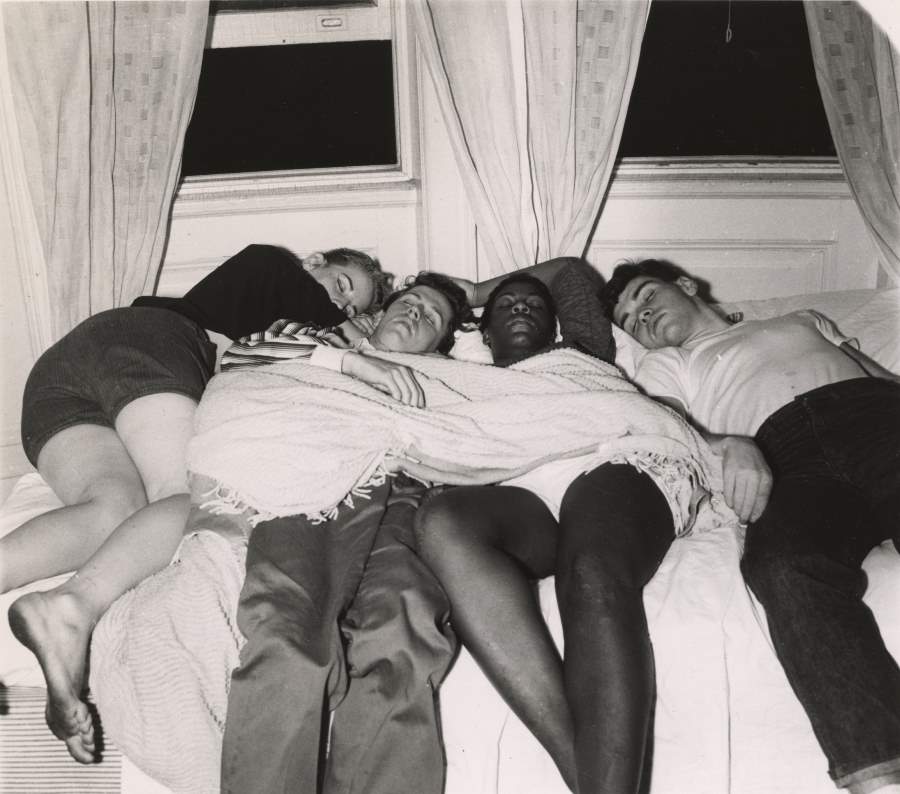

The beatniks were not afraid to talk about sex, which shocked much of the public. They rejected the idea that sex should only happen in marriage. Relationships were often open or short-lived. Homosexuality, still illegal at the time, was openly discussed and accepted among many beatniks. Ginsberg was gay and wrote about his love life in poems and letters. This honesty set the beatniks apart from the rest of society.

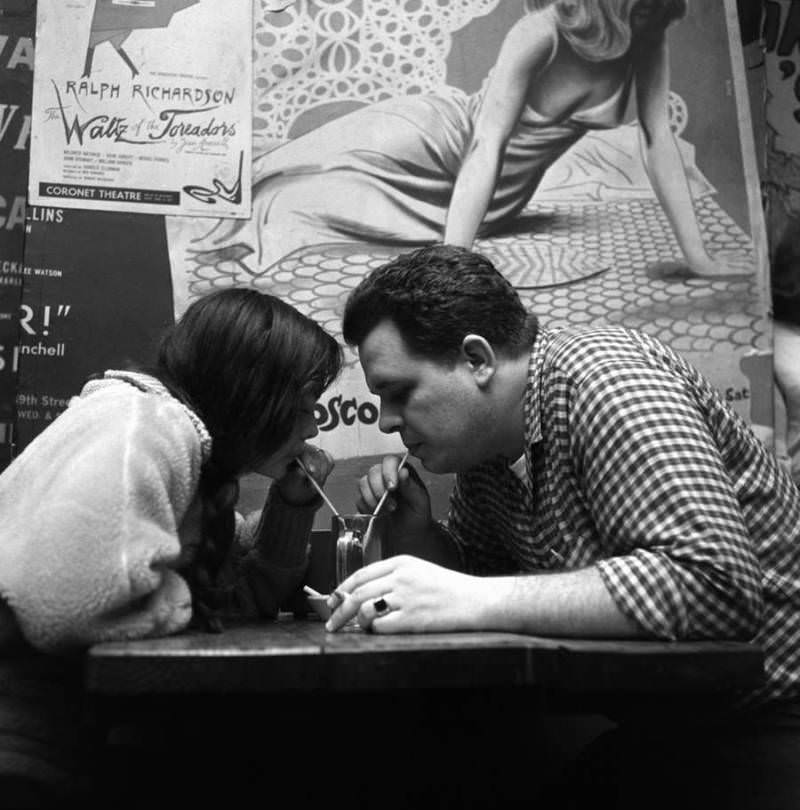

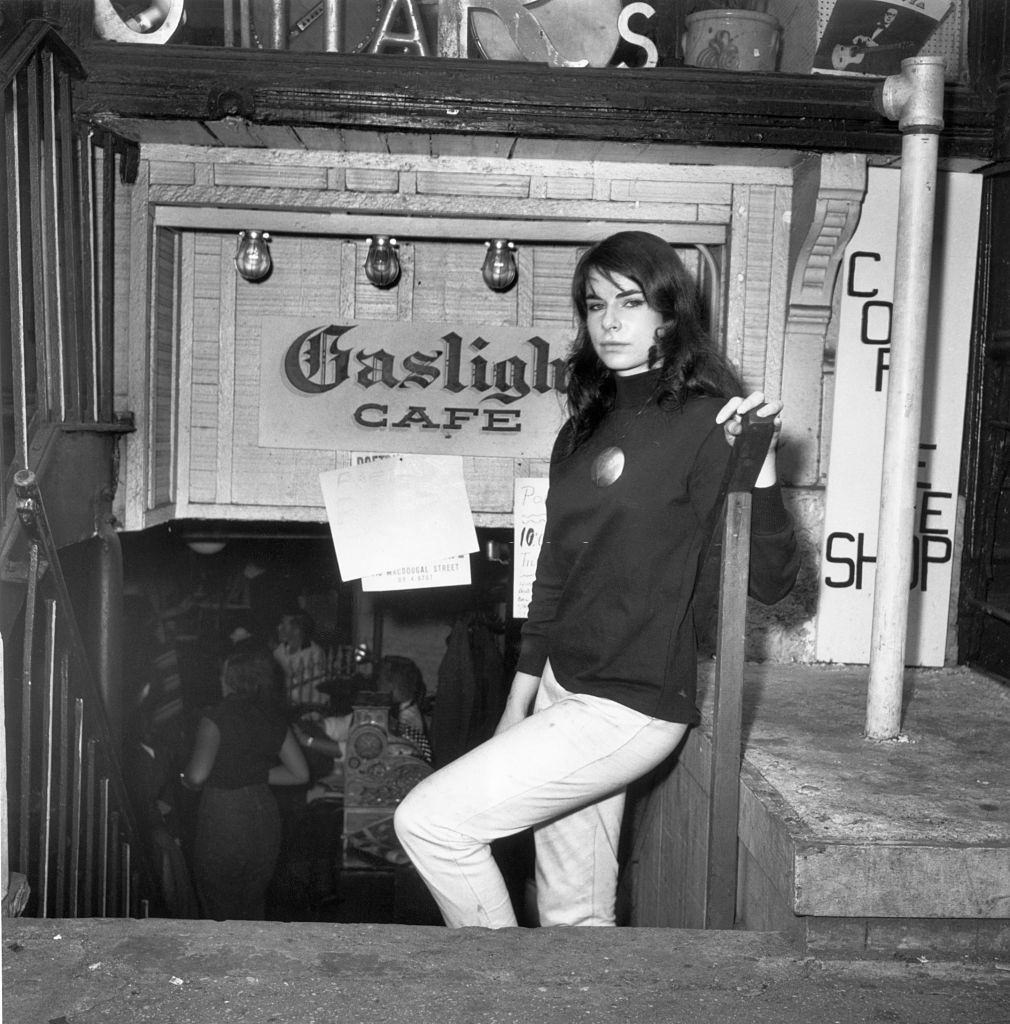

Cafes were the heart of beatnik life in New York. Places like Café Wha?, the Gaslight Cafe, and Café Figaro were full most nights. Some had small stages where poets read, bands played, and actors performed strange plays. Others were quiet places for talking, reading, and sketching. The walls were often covered in art. Coffee was served in chipped mugs. The smell of cigarettes and strong coffee filled the air.

The way beatniks spoke was also different. They used slang from jazz musicians, like “cool,” “dig it,” and “man.” They snapped their fingers instead of clapping. They stretched words, spoke in rhythm, and often used irony or humor. This new language made them seem strange to outsiders but created a strong sense of identity within the group.

Clothing was a statement. Men often wore black or striped shirts, tight pants, and sandals. Women wore long skirts, loose tops, and large earrings. They avoided bright colors and flashy styles. Their look was simple and rebellious. It said they didn’t care about fashion trends or social approval.

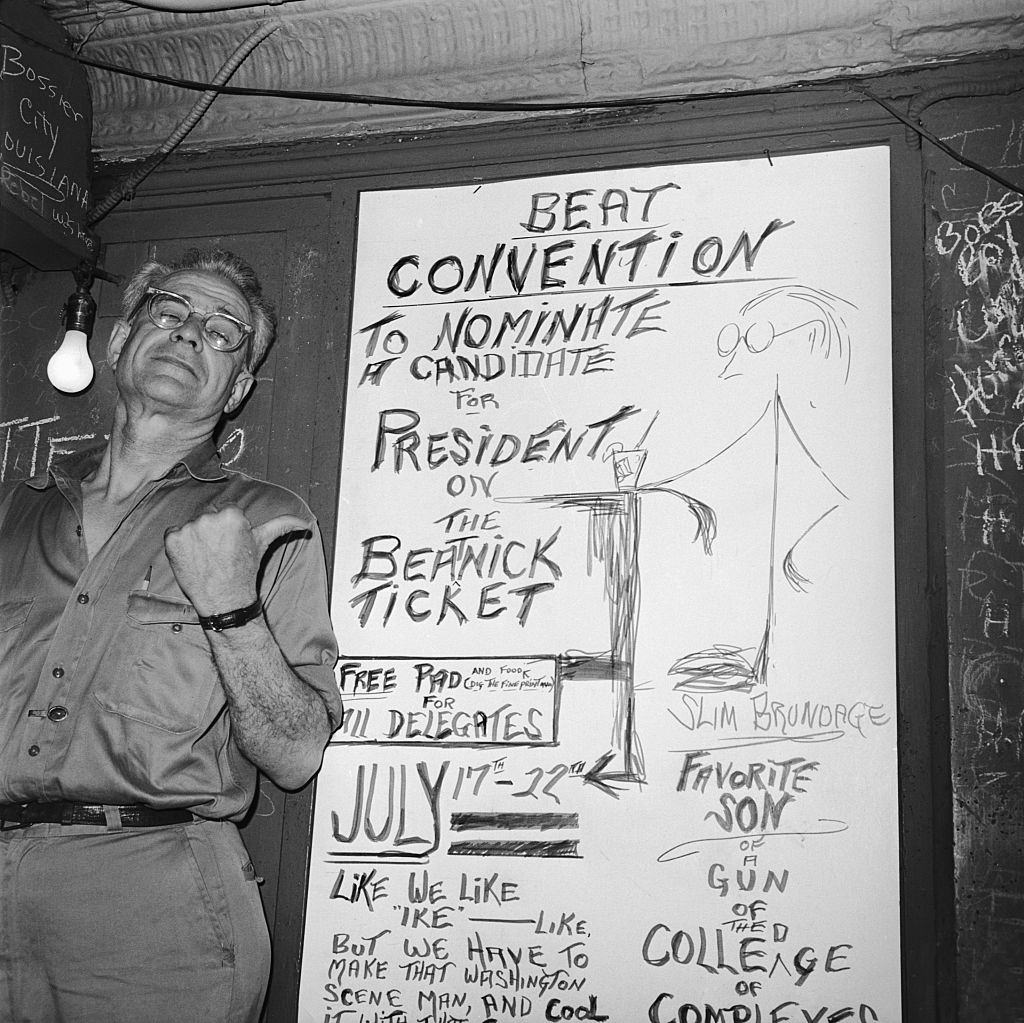

Police and the press sometimes attacked beatniks. Articles mocked them for being lazy or strange. Politicians warned about their bad influence. But the beatniks kept meeting, creating, and sharing. They held poetry readings in apartments and parks. They organized art shows in empty buildings. They formed small publishing presses to print their own books.

Colleges and universities took notice. Young students came to the Village to see what the beatniks were doing. Some professors invited beat poets to speak in classrooms. Debates broke out about whether this kind of writing counted as real literature. Students began dressing like beatniks and using their words.

Some beatniks lived on the edge of poverty. They slept on couches or in cold rooms with no heat. They ate cheap food from diners or didn’t eat at all. But they believed their lifestyle was more real than the one outside their community. They saw the suburbs, advertising, and television as false. They wanted to feel alive through experience, not through comfort.

Not everyone in the Village was a beatnik. Other artists and musicians also lived there. But the beatniks were a loud and visible part of the area. They read poems in Washington Square Park, played drums late into the night, and filled bookstores like the Eighth Street Bookshop with their writings.

By the early 1960s, the beatnik crowd began to fade. Some writers moved away or stopped publishing. Others changed their style. But for a time, in the 1950s and early 1960s, Greenwich Village was the center of beatnik life. Wallace Berman, Diane di Prima, and Gregory Corso joined Ginsberg and Kerouac in keeping the scene alive.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings